Geonarratives for Video Mitigation: Contextualizing Immigrant Cultural Norms and Domestic Violence

Introduction:

Our team collaborated with the Legal Aid Society to aid their efforts in advocating for low-income individuals and people of color who are disproportionately negatively impacted by the New York State criminal justice system. This project is one in a series of projects paired with the Legal Aid Society, with the goal to further fairness and justice in the legal system through the inclusion of geospatial analysis and visuals. We hope that through the use of interviews and videos, judges and prosecutors can visualize a complete picture of the persons accused, resulting in lessened sentences, dismissals of the cases in the interest of furthering justice, and release on recognizance rather than bail.

The utilization of geo-narratives proved to be an imperative aspect of our research to explore the effects of domestic violence on immigrant women, both important themes for this case. In this case, specifically, we discuss how limited English proficiency impacts women obtaining the assistance they need as victims of domestic violence, as well as questioning if criminal prosecution of victims of domestic violence is appropriate, and thus, how to address cases like this without criminalization, promoting healing and restoration of the victim. It is vital to show, through our work, the stories of the client’s life, their relationships, and their histories with trauma, violence, and self-defense, so we can advocate for the help they need and appropriately grasp how these social and geographical forces impact a traumatic response. Due to the age of the person accused in our case, their neighborhood and community, and the lack of social services and resources located in their respective borough, there are many systemic inequities that the client faced, and visual advocacy could assist in promoting equality, fairness, and understanding within the criminal justice system.

Spatial and statistical analysis helps shed light on the multiple factors that explain the incident’s context and why the client may have resisted seeking help sooner. We hope to investigate how the justice system unfairly impacts marginalized communities, how these cases are often related to geospatial realities, and the inequality and blindness to the importance of access to proper resources and institutions that specialize in domestic violence and reach a diversity of survivors due to their readily available language advocacy programs.

The Legal Aid Society

The Legal Aid Society (LAS) is a non-profit organization that provides free legal services to low-income individuals and families who would typically not be able to afford legal representation. They advocate for systemic change that will motivate fairness and justice within the legal system and provide legal services in criminal, civil, and juvenile matters. Since 2019, LAS has been working with filmmakers to produce high-quality videos—incorporating interviews with their clients, their friends, and families, as well as their social workers and psychologists—that provide a contextual, narrative dimension to clients’ cases. Such videos have been introduced in criminal court for wealthier accused but are rarely accessible for low-income individuals like those the LAS typically represents. The vast majority of the 35 mitigation videos the LAS has submitted to prosecutors and judges thus far have achieved reduced sentences and terminated bail conditions, among other favorable outcomes. Video mitigation aims to humanize individuals charged with crimes by explaining their whole circumstances rather than excusing their actions, as well as visualizing racial and economic disparities with a case-by-case strategy employed by LAS and their collaborators, including our team (Meyer 2015, 22).

To combat the epidemic of mass incarceration in our state and city, we seek to paint for the court and prosecution a complete picture and narrative of our client rather than merely the events surrounding the incident in question. Utilizing visual techniques to tell our client’s story, we show how responses to traumatic events often result from socioeconomic, relational, geographical, and environmental factors. The New York State criminal justice system typically fails to take into account the whole life experiences of those accused, including how many legal and institutional systems previously have failed them, perhaps influencing and hindering their decision-making processes and trauma responses. In Julie Urbanik’s essay titled, “Applied geonarratives: Arts-based social geography in criminal defense mitigation,” she speaks to the mitigating factors that the criminal justice system will confront and says, “Defense attorneys focus on mitigating factors, such as lack of a criminal record, mental illness, mental state of the accused, history of suffering abuse, and expressions of remorse,” all of which we hope to include in our research for this case, with a focus on the history of suffering abuse (Urbanik 2021, 1).

For this case, the LAS attorneys intend to file a “Clayton Motion” or a motion to “dismiss in the interest of justice,” under which ten factors are considered. They will work with the history, character, and condition of the person accused, the purpose and effect of imposing an authorized sentence, the impact of the dismissal on public confidence in the criminal justice system, and any other relevant facts, which is where a majority of our research and mapping will reside.

Because our work centers around a legal case, the data and information provided are confidential and thus anonymized. However, we still advocate for publication to raise awareness and resources for reducing inescapable and pervasive imprisonment and criminalization.

Thematic concerns

Because the client, for this case, has limited English proficiency, it is relevant to explore language ecology and forms of language injustice prevalent throughout New York City; it is also essential to discuss the story of place, the client’s migration history, why they moved to the US, and how traditional patriarchal culture in the client’s home country of South Korea negatively impacted the their ability to ask for and receive help in an abusive situation.

Client was subject to traditional South Korean social norms surrounding patriarchal gender roles, anti-feminism, and domestic violence in marriage | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

It is also important to note that there is significant concern for the public’s faith in the criminal justice system if there is punishment and imprisonment for a victim of domestic abuse.

Another critical aspect is that the client is a senior, and the impact incarceration has on the elderly inevitably adds to their trauma and stressful life events pre-dating their prison experience. The lack of research as to their potential threat to the community at their age, as well as the negative impacts that mass incarceration has on their lives, is understudied. Older prisoners are at a higher risk of dying in prison, which impacts their health and potential injury than those who are younger (Maschi et al. 2011, 676). Thus, there needs to be an eradication of older adults being imprisoned.

33.3% of households in the neighborhood of Flushing are also limited English-speaking | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

We hope that by publishing this work, we will contribute to and aid more extensive conversations about the plausibility of restorative justice and prison abolition.

Case

The central focus of this case is how domestic violence and available service providers need to be readily available to those who require aid all around the world, and in our case, specifically within New York City. The lack of available resources with an array of language service offerings is abysmal and tragic, pushing many people to feel isolated and stay in their situations, and how immigration struggles can exasperate domestic violence and abuse and can occur within immigrant families. In our case, within Korean partnerships, there is an emphasis on staying together and maintaining a family home that remains prevalent within Korean immigrant families due to their societal and cultural norms, which further problematizes seeking help and safety due to the lack of available language resources.

The area surrounding the client’s home is particularly densely populated with Korean immigrants | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

While the person accused lived in South Korea for almost fifty years, they moved to New York City in the early 2000s, when there was a massive influx of Korean immigrants prior to and during this time (Lee et al. 2008). Before their move, they were seeped into Korean culture, one that promotes patriarchal gender norms, encouraging and producing subservient wives to their husbands, and maintaining the patrilineal family system (Rhee 1997, 70). It is imperative to understand the rights that women had in South Korea, noting that the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family “was established in 2001 to provide resources for girls suffering from sexual and domestic violence and ensure policies do not discriminate based on gender” (Ahn 2022). This means that for the majority of the client’s life while in Korea, almost forty-eight years, there was no protection for women in abusive marriages, and also, even when some victims reported their situation, they were often sent home, convinced to return to their abuser. Today, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family is under seizure and attack in hopes of the eradication of the ministry, instigating many feminist movement protests to erupt in South Korea. So, while they made steps forward through the implementation of this ministry and its assistance to women, they are currently attempting to roll back the policy and return to their “traditional” attitudes toward women (Rhee 1997, 69).

Research shows that predominantly Korean immigrant communities in the U.S., like Murray Hill-Broadway Flushing, tend to retain and perpetuate Korean social norms and values, particularly with regard to patriarchal gender roles, a women’s subservience to her husband, and a culture of stigma, shame, and silence surrounding matters of domestic abuse | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

One study found that after migrating to the United States, “there is no indication that Korean husbands have changed their traditional beliefs of rigid marital roles,” meaning that the Korean immigrant men have held firm to their core values of the family (Rhee 1997, 67). In a questionnaire provided to Korean immigrants in Los Angeles, the immigrants reveal that they are still attached to their culture, finding that 91.6% of females believe in the importance of familial commitment, with 78.5% of men continuing the traditionalist views on gender and gender roles (Junaid). Due to the adherence to societal norms, “research findings indicate that wife abuse is much more prevalent among the immigrant Korean population in comparison to other ethnic groups” (Rhee 1997, 63). The impact of their cultural background, including the emphasis on patriarchy and family harmony, the lack of language access, and economic hardship that pairs with social discrimination of immigrants, leaves an opening for physical abuse to occur and continue without any ramifications, assistance, or help (Anderson 2014). In interviews with Korean immigrant women in Los Angeles, 60% reported being battered during the entire marriage period. This is compared to 12% of American women who reported battery in their marriage, an astounding difference in experience (Rhee 1997, 68).

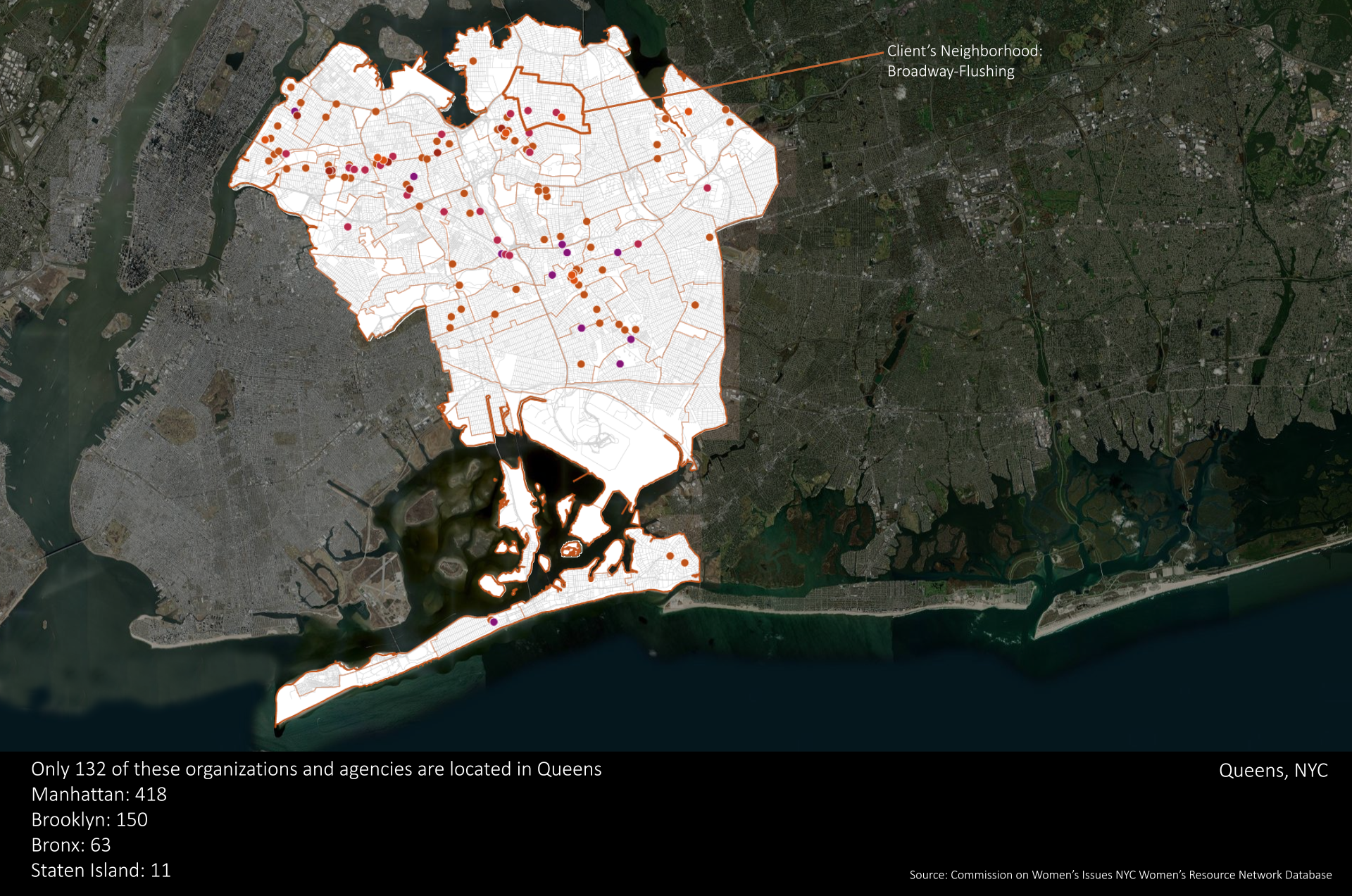

Mapping the available women’s resources in Queens, showing the sparcity of accessible resources within the borough of Queens in comparison to Manhattan or Brooklyn | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

Our research and mapping found that even though these statistics are jarring and evident, access to resources is still limited, even in New York City. Queens, specifically Flushing, comprises many Asian-born immigrants, with large populations of Korean-born immigrants, specifically in Flushing, Queens, where the client and her husband reside. There are a few resources available in the client’s neighborhood that employ Korean-speaking staff, but the impacts of domestic violence and battery result in shame, embarrassment, fear, depression, a damaged sense of self, and helplessness, meaning that even when resources are accessible, victims may resist seeking help (Rhee 1997,74). Youn Mi Lee mentions in the text “Theoretical Perspectives for Understanding Marital Abuse among Korean Immigrant Women in the United States” further that “Korean immigrant women who experience abuse are likely to be physically, psychologically, and socially vulnerable because of language barriers, isolation from their family of origin, and unfamiliarity with a new country” (Lee 2010, 3). This proves the importance of language justice and access to resources conducive to their native language so they can share their experiences and ask for help. In the text “Global Language Justice Inside the Donut,” Suzanne Romaine, the author, writes, “Information in languages and formats people can understand can help save lives in a crisis, but language is usually not seen as a priority in emergency responses. Misinformation, mistrust, fear, and panic spread quickly, leading people to hide… secretly” (Romaine 2023, 77). This massive inequality occurs in New York City and around the world. The importance of language justice can save people’s lives and in our case and research, can allow for a safe place for someone to be seen, heard, assisted, and potentially saved from their abusive and violent situations rather than further reinforcing the feeling of isolation, mistrust, and fear.

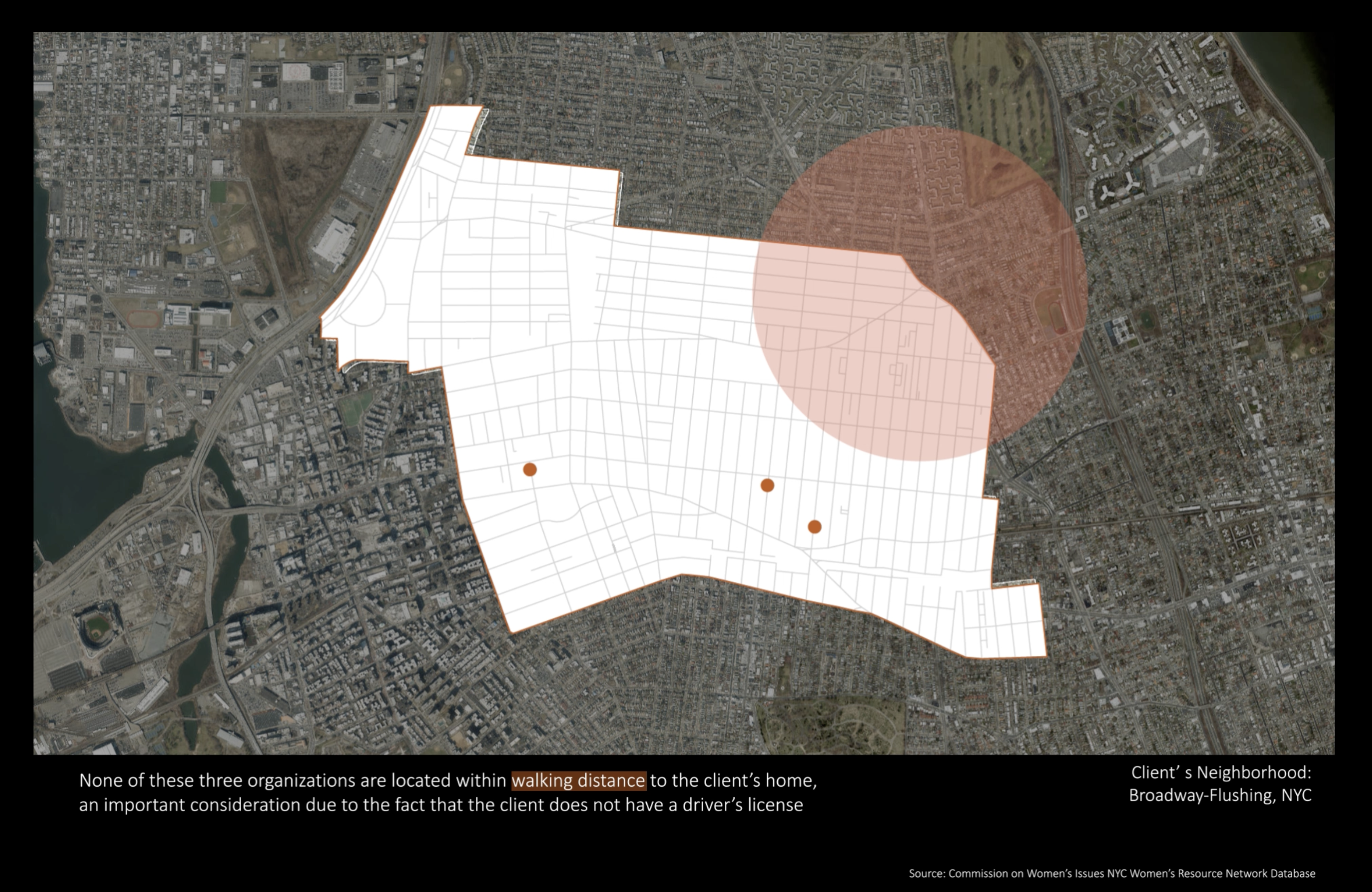

While there are three social services located within the neighborhood of Flushing, Queens, only one offers domestic violence assistance and they are not walkable from her home. This further creates a diversion from obtaining help in her situation | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

Takeaways

-

Privacy and Data Integrity in Legal Cases: Handling sensitive data with the utmost confidentiality is crucial, particularly when publicizing geospatial information. Ensuring that all shared data preserves the anonymity and security of the individuals involved is paramount.

-

Accuracy and Completeness of Case Data: The complexity of the cases managed by the Legal Aid Society requires that all utilized data be current and thorough to support case narratives and legal strategies accurately.

-

Collaborative Communication with Diverse Professionals: Effective partnerships with various professionals demand clear communication and mutual understanding to ensure that all project outputs are practical, accessible, and meet the varied needs of all project stakeholders.

-

Advocacy and Legal Support through Legal Aid Society: Collaboration with the Legal Aid Society has underscored the importance of supporting legal advocacy for domestic violence-related issues.

-

Domestic Violence: This is, unfortunately, a reality for many people nationally and globally, and victims’ access to resources within their neighborhoods is of the utmost importance.

-

Language Justice: Our research found that the lack of language-inclusive services for survivors of domestic abuse, especially in Queens, was disappointingly low, meaning that survivors with limited English proficiency are less likely to seek or receive support.

-

Cultural Awareness/Relativism: Cultural and social values affect people’s ability to see a future outside of their traumatic and painful experiences, especially in predominantly Korean immigrant communities, where harmful gender norms are deeply entrenched and reinforced.

Video | Source: Authors Jane Cole, Bryce Emerson, Serena Stedeford

Bibliography

Ahn, Ashley. “Feminists Are Protesting against the Wave of Anti-Feminism That’s Swept South Korea.” NPR, December 3, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/12/03/1135162927/women-feminism-south-korea-sexism-prote st-haeil-yoon.

Anderson, Laurie. “Professor Studies Domestic Violence among Female, Korean Immigrants.” UGA Today, December 12, 2017. https://news.uga.edu/professor-studies-domestic-violence-among-female-korean-immigrants/.

Junaid, Muhammad. “Flushing Koreans.” The Peopling of New York. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/napoli13/flushing-koreans/.

Kim, Bitna, Victoria B. Titterington, Yeonghee Kim, and William Bill Wells. “Domestic Violence and South Korean Women: The Cultural Context and Alternative Experiences.” Violence and Victims 25, no. 6 (December 2010): 814–30. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.25.6.814.

Lee, Youn Mi. “Theoretical Perspectives for Understanding Marital Abuse among Korean Immigrant Women in the United States.” Asian Women, December 31, 2010. https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2010.12.26.4.1.

Maschi, T., K. Morgen, K. Zgoba, D. Courtney, and J. Ristow. “Age, Cumulative Trauma and Stressful Life Events, and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms among Older Adults in Prison: Do Subjective Impressions Matter?” The Gerontologist 51, no. 5 (August 17, 2011): 675–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr074.

Meyer, Chance. “Mitigation Paradigms: What Reduces Criminal Sentences, Explanation or Excuse?” The Florida Bar, 2015. https://www.floridabar.org/the-florida-bar-journal/mitigation-paradigms-what-reduces-criminal-sentences-explanation-or-excuse/.

Rhee, Siyon. “Domestic Violence in the Korean Immigrant Family.” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 24, no. 1 (March 1, 1997). https://doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.2397.

Romaine, Suzanne. “2. Global Language Justice inside the Doughnut.” Global Language Justice, December 31, 2023, 68–97. https://doi.org/10.7312/liu-21038-005.

Urbanik, Julie. “Applied Geonarratives: Arts-Based Social Geography in Criminal Defense Mitigation.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4, no. 1 (2021): 100159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100159.

Yean-Ju Lee, and Larry Bumpass. “Socioeconomic Determinants of Divorce/Separation in South Korea: A Focus on Wife’s Current and Desired Employment Characteristics.” Development and Society 37, no. 2 (2008): 117–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/deveandsoci.37.2.117.