'Benign' Development: Asian Foreign Developers in Asia

1/ Introduction

In post-colonial and de-colonial studies, Western-led developments in Asia have been studied and critiqued extensively. However, less attention has been given to developments led by foreign Asian developers in Asian countries, or ‘Asia-to-Asia development’, especially using neo-colonial and neoliberal analytical frameworks. In less developed regions in Asia, local governments perceive developers from more developed Asian countries to have better regional knowledge and contextualized economic growth strategies that they can replicate in their own cities. As compared to Western developers, these Asia-to-Asia development practices are thought to be not only more benign, but also more attainable. This study draws on four case studies to investigate if Asia-to-Asia developments are truly beneficial to local stakeholders, and argue for further critical research into this under-researched field.

This study draws on two theoretical frameworks for analysis. In Foreign Direct Investment and Development, Theodore Moran (1998) classifies the dynamic between foreign direct investment and development as either “benign” or “malign”. The benign dynamic is supposed to break the cycle of poverty and inequality by improving productivity, local revenue, and community development, which leads to higher economic growth (p. 19). Meanwhile, the malign model emphasizes the possibility of foreign entities enjoying the imperfect domestic market to extract more profits, driving domestic producers out of business and draining the local capital of the host country instead of closing the inequality gap (p. 20).

In Neo-Colonialism and the Poverty of ‘Development’ in Africa (2018), Langan argues that foreign intervention in Africa is a neo-colonial phenomena. These interventions come in both aid and development, and are legitimized as part of a “virtuous endeavor” to bring about economic development to local contexts. However, these interventions tend to bring about negative effects such as exacerbating existing conditions of ill-being and poverty. Hagmann & Reyntjens’s Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development without Democracy (2016) further extends Langan’s argument that foreign intervention tends to work in tandem with authoritarian one-party state, which further strengthens the regime at the expense of local populations who typically get dispossessed.

This project aims to examine the impacts of Asia-to-Asia development. Key conflicts identified across the four case studies examine the power dynamics between local stakeholders and foreign developers and the role of the state in furthering foreign interests.

2/ Introducing the Case Studies

The following four case studies in Vietnam, Laos, India, and Indonesia have been selected for this analysis to show the similarities and differences across project use types and scales. Despite the key differences in use and scale, with projects ranging from 29 hectares to over 11,500 hectares, they share common conflicts pertaining to land use, resource sharing, and globalization, as discussed in a later section (section 3).

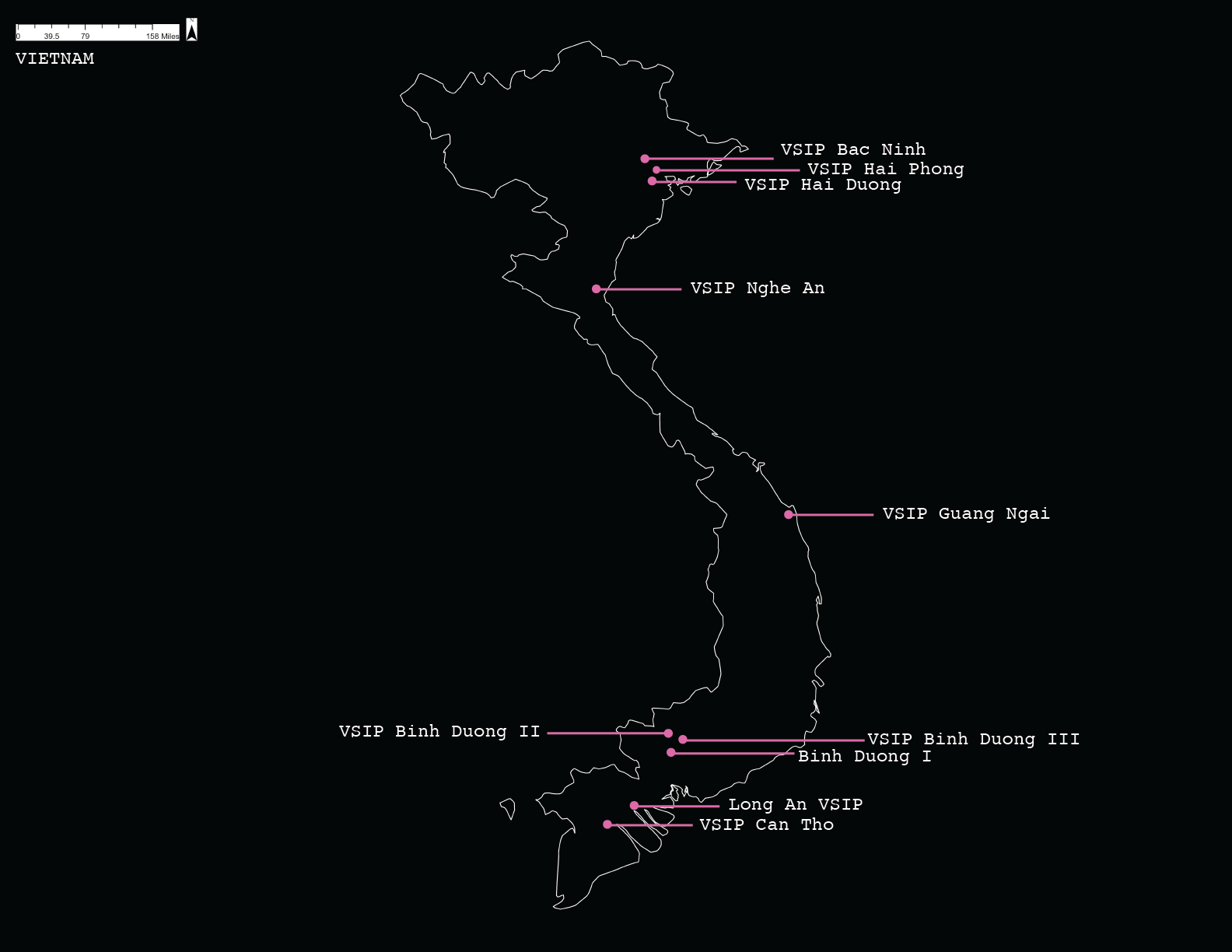

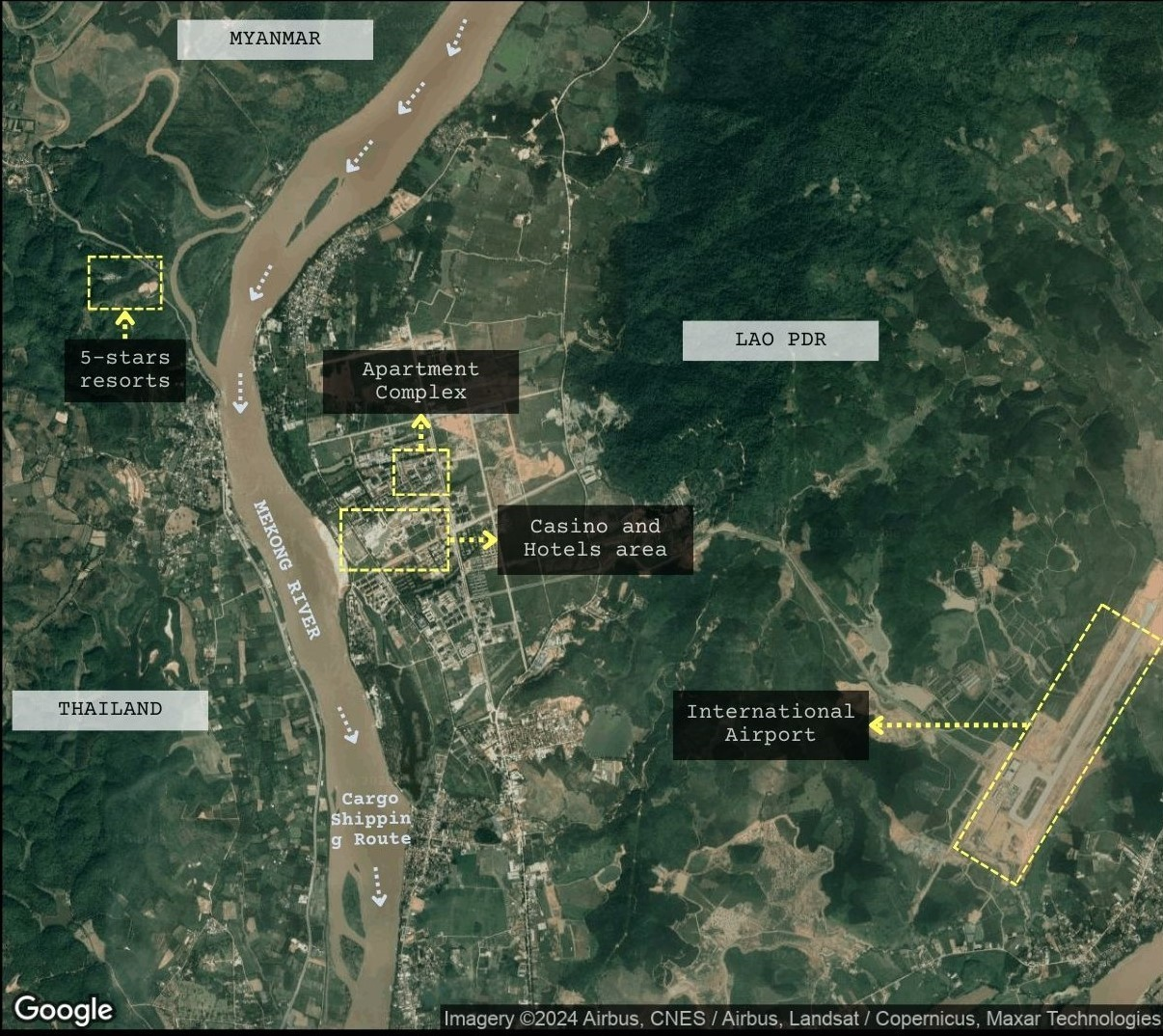

2.1/ Vietnam: Vietnam-Singapore Industrial Parks

The Vietnam-Singapore Industrial Parks (VSIP) began in 1996 as a bilateral government-led project arising out of two complementary ambitions from both the Vietnamese and Singaporean governments – for the former, they wished to emulate Singapore’s model of industrialization and modernization to encourage greater economic growth and job employment; for the latter, this project allowed Singaporean developers leverage on their master-planning expertise to benefit other Singaporean and foreign investors by tapping into cheaper regional labor.

VSIP is a joint venture project between Becamex Investment and Industrial Development Corporation (Becamex IDC), a Vietnam state-owned enterprise, and Sembcorp Development, a Singaporean land and real estate developer. Becamex IDC provided the land bank for the developments, while Sembcorp Development provided their expertise in green and mixed-use urban planning, global marketing outreach, and the Singapore reputation and branding (Sembcorp Development, 2021). The first project was a 500-hectare development in Binh Duong province, an hour outside of Ho Chi Minh City. Since then, there have been a total of 14 VSIP projects throughout the country dedicated to light manufacturing industries and supplementary residential developments. Each project ranges from 150 to 2,045 hectares in size and totals over 11,500 hectares, approximately the size of Queens (“Singapore-Invested Industrial Parks in Vietnam: An Overview”, 2023).

System Diagram: Development partners & industrial park partners

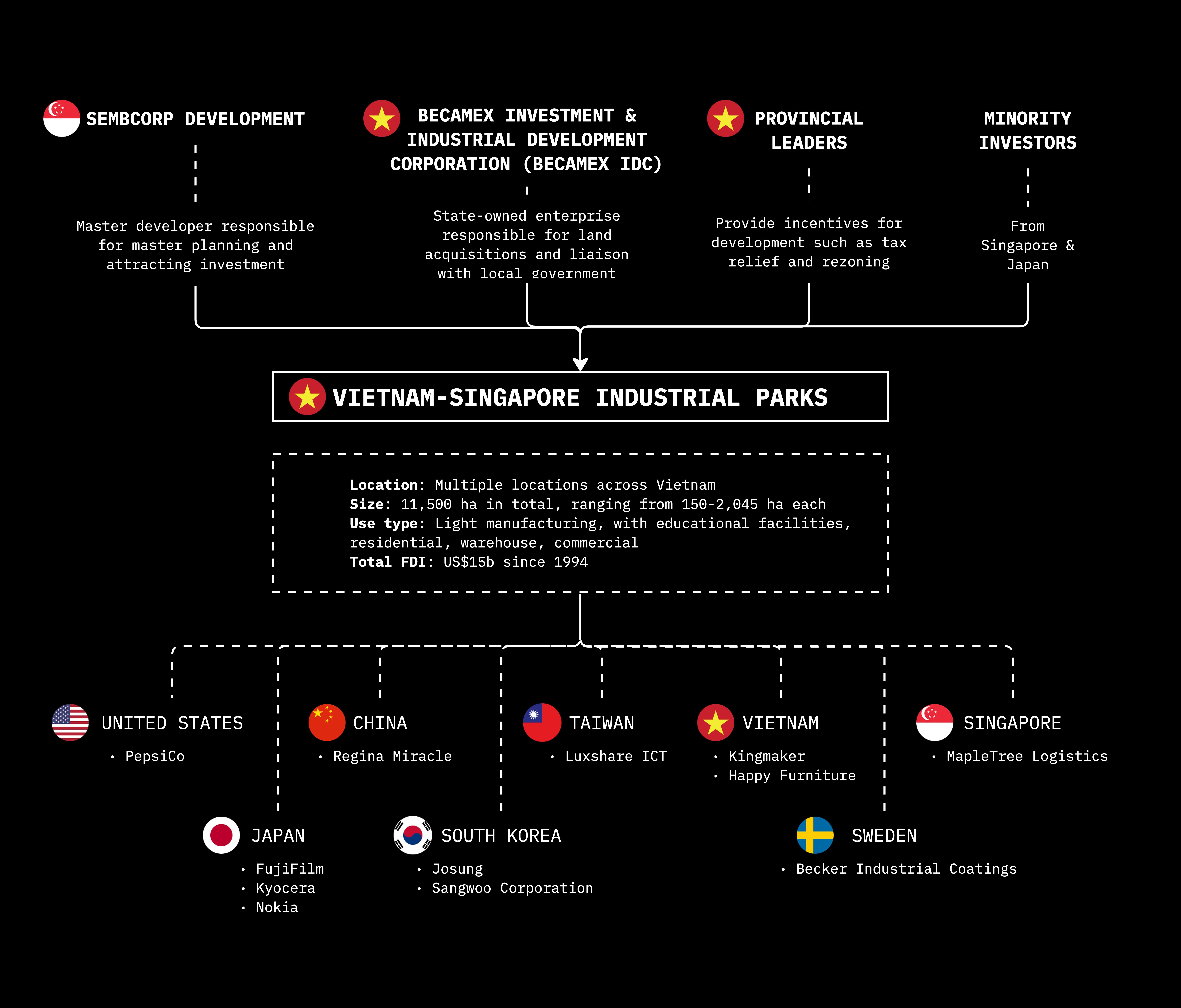

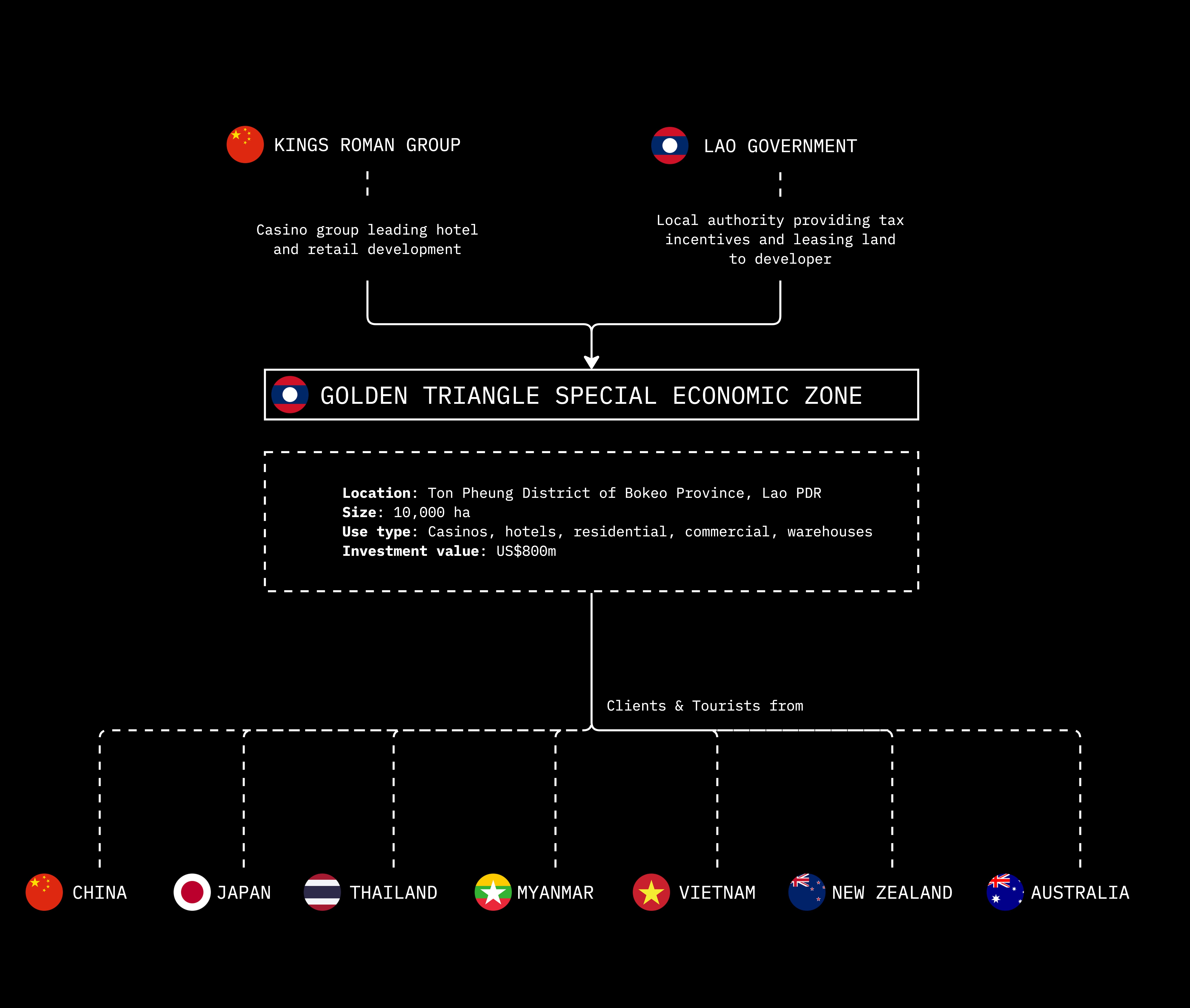

2.2/ Laos: Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (SEZ)

Located on the Laos bank of the Mekong River, this SEZ is strategically located at the intersection of Thailand, Myanmar, and Laos. The Laos Government signed an agreement of 99 years lease agreement with Hong Kong-registered Kings Romans Group in 2007 to develop a 10,000-hectare area in Ton Pheung, Bokeo Province – 3,000 hectares of duty-free zone, called the Golden Triangle SEZ. The development aims to attract foreign direct investment and boost economic growth in the region.

The development of this area is central to the opening of casinos, hotels, resorts, and an international airport. The area primarily attracts Chinese tourists and uses Chinese renminbi and Thai baht as the main currencies. This area has been closely associated with illegal industries such as wildlife trade, human trafficking, sex trade, narcotics smuggling, and money laundering that cater to transactions for Chinese, Hong Kong, and Australian clients. This SEZ is part of the government’s “Turning Land Into Capital” policy established in 2006 (Kuaycharoen, et al, 2020), rooted in the marketization of land for profit and government revenue. Apart from the significant land use change, smallholder landowners who rely on their livelihood through agriculture are evicted from their land as the government reallocates the state land for foreign investors.

System Diagram: Development partners & Secondary foreign-direct investment partners

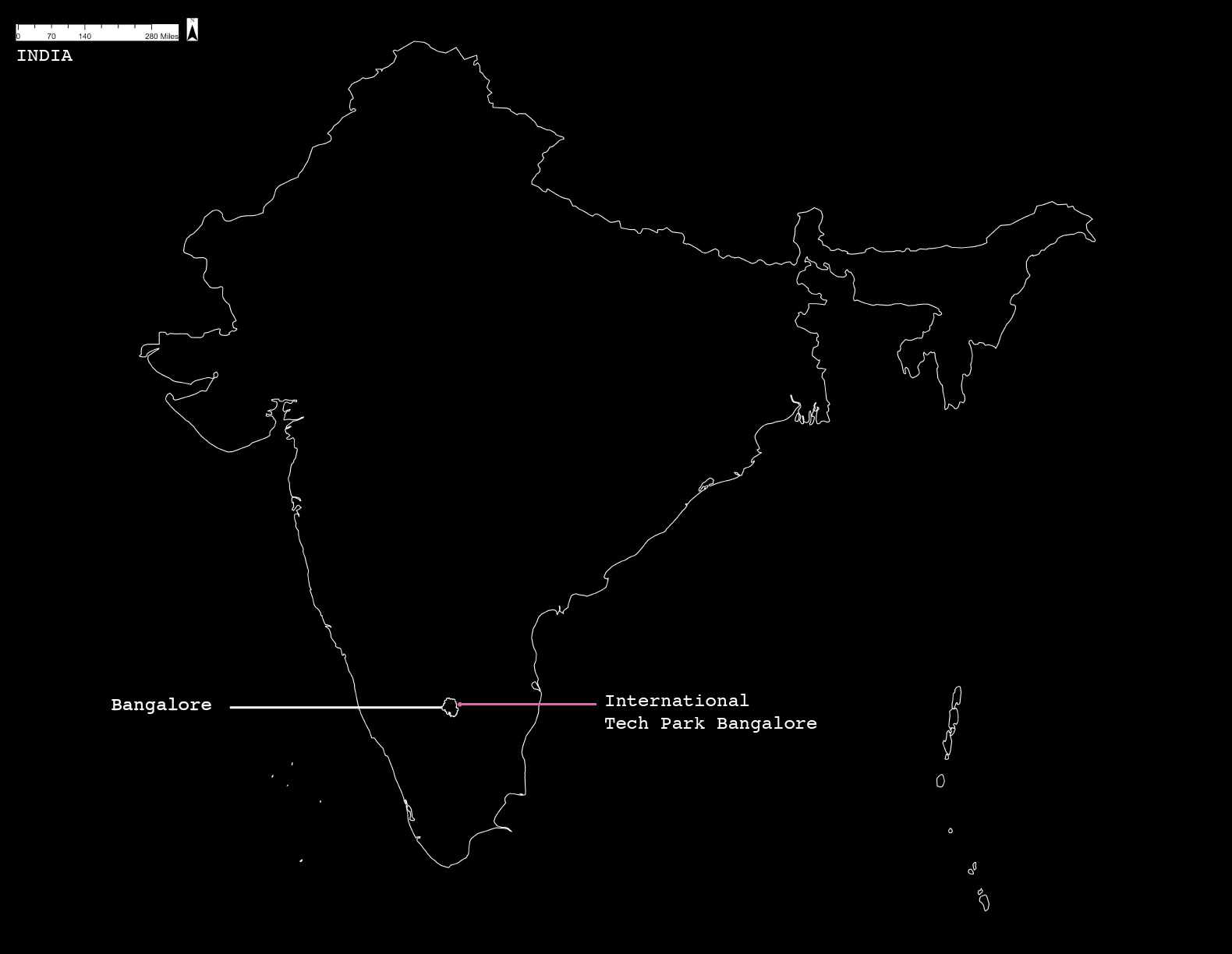

2.3/ India: International Tech Park Bangalore

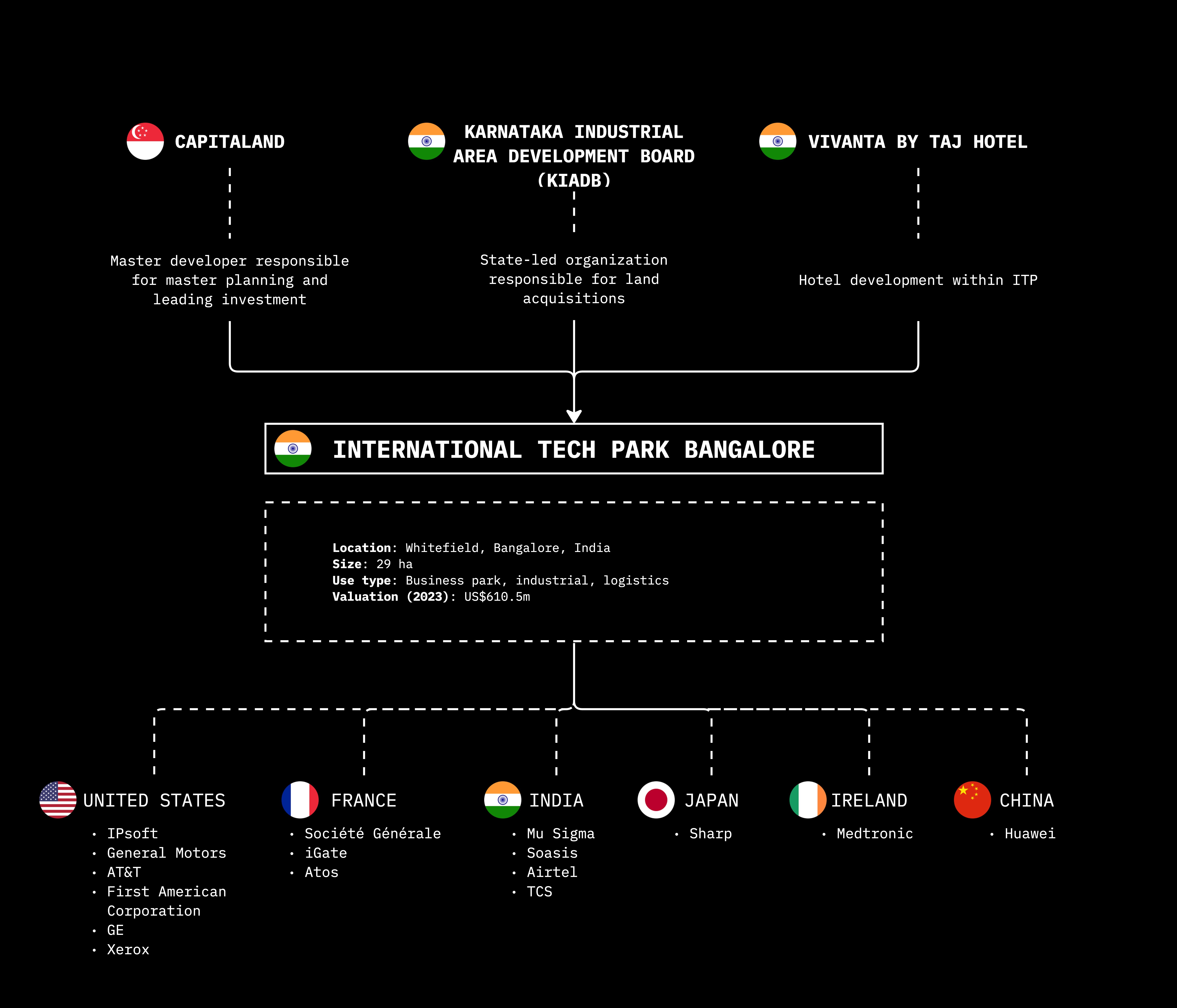

International Tech Park Bangalore (ITPB) is a tech park located in Whitefield, Bangalore, 18 km from the city center. According to a 2023 valuation, the development is valued at $610,539,832 USD (Capitaland). The park comprises a total 29 hectares of office space, retail mall, hotel, and amenities such as banks, restaurants, and sporting arenas. Built in 1994, ITPB served as the first large-scale example of the ‘work-live-play’ environment in India and is used as a model for IT park projects in Bangalore, which is often touted as ‘India’s Silicon Valley’. There are currently over a dozen tech parks in Bangalore housing over 67,000 companies.

The park was created as a joint venture between India and Singapore in 1994 to replicate Singapore’s infrastructure. Capitaland Ascendas is the lead partner of the Singapore consortium of ownership, owning 94 percent of the park. Karnataka Industrial Area Development Board (KIADB), a State-led organization responsible for land acquisitions for industrial and infrastructure purposes controls the remaining 6 percent. The project has also attracted Indian companies such as Taj hospitality group.

System Diagram: Development partners & tech park industry partners

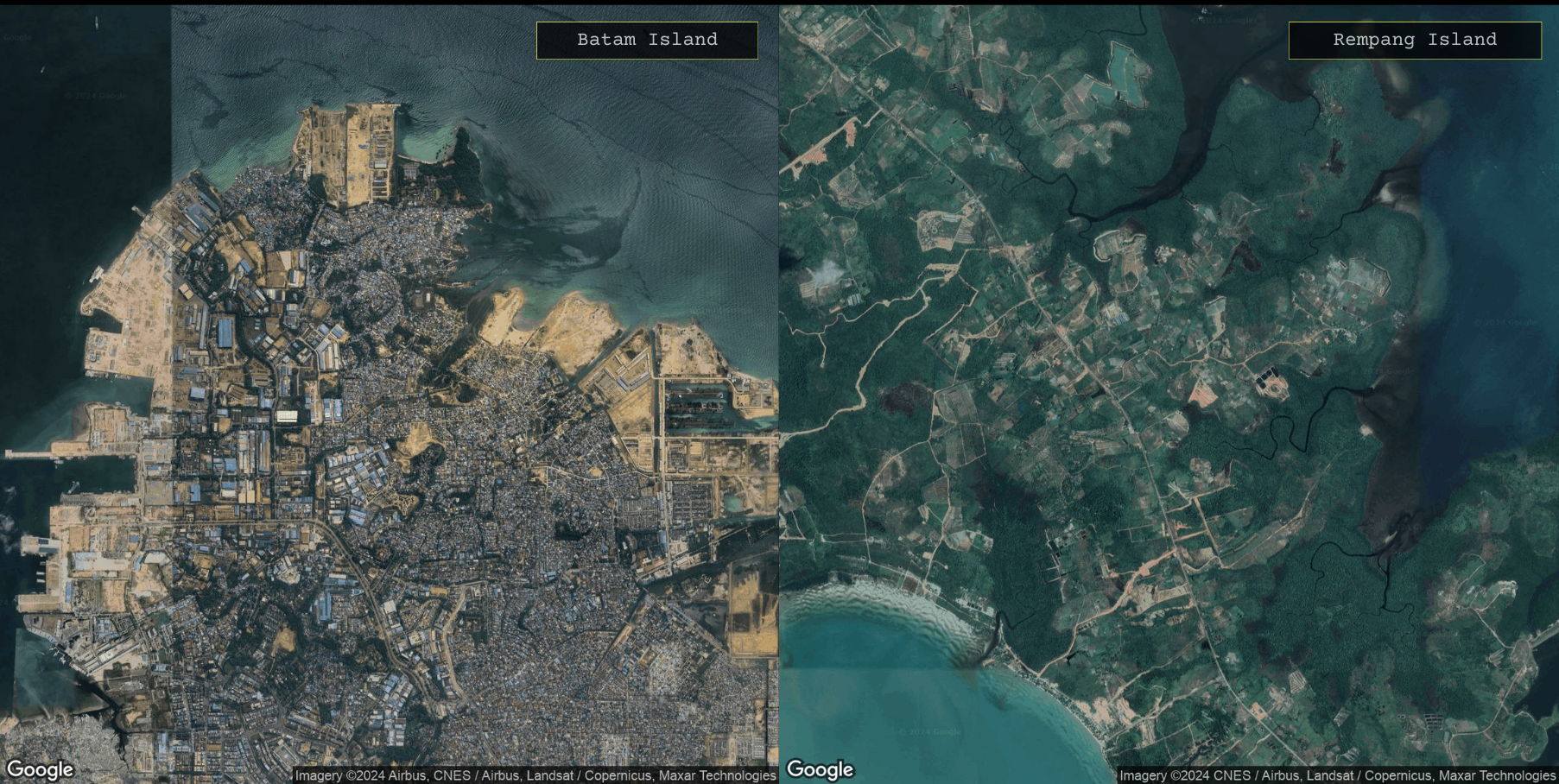

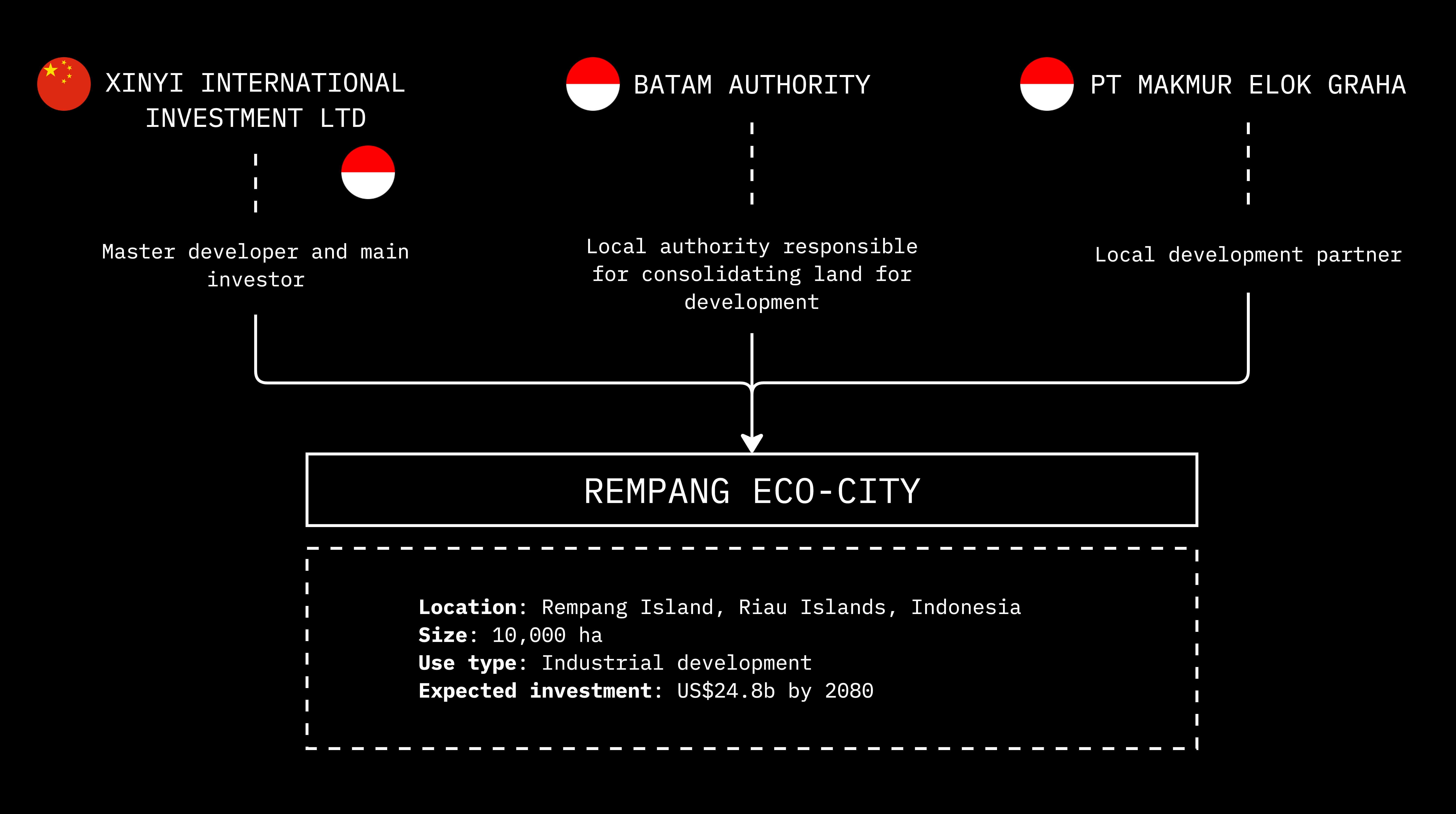

2.4/ Indonesia: Rempang Eco City

The Rempang Eco City project is a joint project between the Batam Indonesia Free Zone Authority (BP Batam), local Indonesian company PT Makmur Elok Graha (MEG), and China’s Xinyi Glass, the world’s largest producer of glass and solar panels (Llewellyn, 2023). BP Batam is a central government institution responsible for managing, developing, and constructing free trade zones and free ports in Batam, Indonesia (BP Batam, 2024).

Located on Rempang Island, the project site is close to Malaysia and Singapore and encircled by several smaller local Indonesian islands. The project is not yet built and is anticipated to cover around 42,000 acres (17,000 hectares) of land, with the development of industrial, service, and tourism areas being built on Rempang Island (Clark, 2023). The project, titled “Rempang Eco-City,” is claimed to include several sustainability elements, such as green infrastructure, renewable energy, eco-friendly building design, recycling infrastructure, and sustainable transportation options. It is also advertised to hold immense potential for economic development and local job creation, utilizing the locally available quartz sand resources, an important resource in the production of glass and solar panels (Herwinda, 2023).

While the Rempang Eco city project is yet to be built, its immediate surrounds contain other Indonesian islands that have also received foreign direct investment for large-scale industrial development, specifically from Singapore immediately to the Islands’ North. Given the close proximity of these developments, and the similar economic-zone master planning approach, Islands such as Batam set a precedent for anticipated land use and socio-political changes likely to occur in the Rempang Island.

System Diagram: Development partners

3/ Themes of Conflict

Along all four of the projects described above, three key themes of conflict emerge: land-use change and decision-making, ecosystem for displacement & dispossession, and localized sites for global contests.

3.1/ Land Use Dynamics and Decision Making

Foreign developers wield significant influence on local land use dynamics. Typically, local governments are responsible for land use planning, approving development permits or zoning changes for their jurisdiction. However, in such large-scale urban and industrial developments, foreign developers are given substantial concessions or quasi-governmental authority over large masses of land, making executive decisions on land use (Shatkin, 2016). In such situations, the interests of foreign developers are prioritized over local interests because of the promised local economic development these projects claim to bring. These concessions and prioritization can be seen in the blanket approval of master plans for large plots of land, tax incentives, and streamlined approval processes which often come at the expense of local communities’ concerns.

In VSIP, the land used for development was mostly used for agricultural purposes before development. The first industrial park, VSIP Binh Duong I, meant over 500ha of agricultural land, alongside livelihoods, homes, and food sources, were lost. Maps of the development over time, as shown above, expose the rapid urban transformation of these sites. This project was also catalytic in driving rapid urbanization and industrialization in surrounding areas, with at least three more industrial parks developed in quick succession in the area alongside new residential development. These maps show that low-rise housing constructed from less durable materials increased in density and sprawl surrounding the industrial park, suggesting that housing development is unable to match the industrial growth of the region, particularly in areas right outside the jurisdiction of the foreign developer. This highlights the limitations of having developments led by private foreign interests, who are not beholden to local land politics or the welfare of local residents in their pursuit of profit.

Similarly, the ITPB, other tech parks, and the local government in Bangalore have been heavily criticized for failing to contribute quality infrastructure and basic amenities to local residents. Tech parks in the area have compounded existing transportation infrastructure issues, which are exacerbated by rural-to-urban migration and rapid unplanned urban development. Living costs in the area have also increased as a result of the rapid urbanization and tech park developments. Despite their overwhelming support for tech park development in the area, the government has failed to provide local workers and residents with basic infrastructural improvements A “Save Whitefield” protest in 2015 drew 8,000 people protesting against ‘the apathy of the local government authorities’ to the poor state of the infrastructure in the area. Protestors voiced their desire for basic amenities like roads, footpaths, and streetlights (Economic Times). Despite the huge investments in the area to build tech hubs, there is a clear disconnect between local and national interests. In an effort to progress India’s economic development goals and emulate Singapore’s success, basic infrastructure needs are ignored and continue to create discontent among local residents.

The Golden Triangle SEZ is part of Lao’s market-oriented economic reform program that started in 1986, which targets private sector growth in order to strengthen the local economy (Kuaycharoen, et al, 2020). It is also intended to accelerate socioeconomic development at the national level by attracting foreign investment and diversifying the economy that initially relies largely on agriculture. Despite the incentives given to the developer, such as generous tax breaks and import-export exemptions, the developer still put in further requests for more land, challenging the local government’s land use plan. There is also a disproportionate benefit between what the developer gained compared to the local community, as evidenced by the developer’s failure to build infrastructures for the local community as agreed upon in the master plan. Instead, the developer has decided to pursue their own business development agenda by building a $150 million international airport along with a new port on the Mekong River (Radio Free Asia, 2020) made specifically to improve tourism access to the Golden Triangle casino area.

In Batam and Rempang Islands, Otorita Batam was established in the 1970s with the aim of transforming Batam Island into a prominent economic hub in Asia, rivaling Singapore (Renaldi, 2023). Otorita Batam “is a government agency responsible for economic development and management – in the 1970s to transform the island into Asia’s powerful economic hub due to its strategic trade route. At that time, Batam was intended to compete with Singapore” (p.1). Presidential decrees in 1973 and 1992 expanded Otorita Batam’s authority to only manage Batam Island, but also the neighboring islands of Rempang and Galang,and granted Land Management Rights on the islands, which has significant implications for local land use dynamics. The local indigenous groups of the islands, including the Indigenous People’s Alliance of Nusantara (AMAN), on the other hand have raised concerns about the impact of granting land rights to Otorita Batam, which ultimately obstructs residents from obtaining legal recognition of the land rights. Furthermore, issues of lack of consultation and consent with local indigenous groups regarding land use decisions have been raised, regardless of several political promises made. Despite the unresolved land tenure issues in Rempang, the Rempang Eco-city Project has been designated a National Strategic Project, indicating continued prioritization of development initiatives over local community concerns.

3.2/ Ecosystems for Displacement & Dispossession

Massive displacement of existing local communities were conducted in the lead up to these large-scale foreign-led developments. Local communities were not only displaced from their land, but were also dispossessed of their rights in the name of economic pursuit. Local governments help to facilitate such an environment by being the active agents behind displacements.

Binh Duong, the province where the first VSIP project was launched, was often claimed to be a greenfield development project. In other words, the land where the industrial park was slated to be developed had nothing on it prior to development. However, in comparing LandSAT images from 1995 before the groundbreaking of VSIP and 2000, significant built up land disappeared and became “green.” These images suggest mass displacement of existing local residences had indeed taken place in the effort to consolidate land for industrial development, and was led by the local authorities who were in charge of land acquisition and preparation. Language used in investment promotional materials for VSIP highlights local populations as “active workforce” or having high literacy rates (VSIP, n.d.), further exemplifying that local authorities and developers view local residents as expendable resources instead of active community stakeholders.

Bangalore is currently facing a severe water crisis, as the issue of water scarcity has reached critical levels and residents grapple with conservation measures for their daily needs. While climate change has impacted the region, the city’s government failure to invest in water management is the true culprit of the water crisis. As city officials have focused investments in bolstering the tech ecosystem in Bangalore and the surrounding area in the past decades, water management has not evolved since the 1960s as otherwise healthy aquifers continue to draw dry due to the unmitigated spread of urban wells (New York Times, 2024). In recent months, the tech hubs in Whitefield have received media attention for exacerbating the water crisis. Many technology companies housed in Whitefield require workers to be in office for all of or most of the week, increasing the water needs of the area. Local residents and tech employees have united to rally against in-person work requirements (Economic Times), but the tech companies and local government have both been slow to act up to this point, although it is clear what steps need to be taken to mitigate and solve the crisis.

The development of the special economic zones in the Bokeo Province has put vulnerable communities at risk of displacement. As the Lao government exercises its eminent domain, many smallholder farmers’ ancestral land plots have been taken away. In the case where the communities refuse to transfer their land use rights, there will be prolonged disputes over the compensation while the developer holding the current rights of use through the contract with the government would continue conducting land clearing and construction of projects as scheduled in their own timeline. Since 2007, the development of the Golden Triangle casino and hotel areas has been aggressively pursued, with a palace-like architecture style and large water feature areas mimicking the staple luxurious casino establishments in other cities worldwide. Meanwhile, the province’s local community poverty rate reached over 44.4%, the second highest in Laos (Land Equity International, 2020; World Bank, 2014), with minimal infrastructure built in the village areas.

Building the Rempang Eco-City in Indonesia, will also involve displacing 7,500 local indigenous groups in Rempang 60 km inland, particularly those that rely on fishing for their livelihoods (Sidiq, 2023). The indigenous community has occupied Rempang for over 200 years, but in 2001-2002, the government granted land rights to a private company, leading to conflicting land use claims (Salma, 2023). Despite living on the island and close to the sea for generations, these community groups do not have legal land ownership and, therefore, have limited say in the use of the land in the current day.

The displaced communities are said to be relocated to condos nearby, removing them from the sea shoreline and limiting their access to local fisheries. In response, there have been several protests in the past year from the indigenous residents of Rempang City, resisting relocation and seeking their rights to their land and access to the sea. As of today, the residents have received several notices from the government to relocate. The development of relocation homes for the residents broke ground in 2023, and the project is set to conclude the construction of over 900 more units by the end of 2024.

3.3/ Localized Sites for Global Contests

The third theme of conflict surrounds these projects being localized sites for global contests, ranging on issues such as economic development, broader geopolitical dynamics, interboundary humanitarian and legal challenges such as human trafficking and money laundering, and emergence of urban sustainability in the face of climate change.

From afar, there seems to be little report on any frustrations local residents might have towards VSIP projects. However, tensions relating to the disproportionate benefits to the local community from massive foreign investments are constantly in the background. During the height of the South China Sea dispute, the local Vietnamese community protested within VSIP and burnt Chinese-owned factories to demonstrate their anger (BBC News, 2014). VSIP was seen as the focal point of the geopolitical conflict for a number of reasons. First, the Chinese-owned factories are much more accessible to workers living in less urbanized areas compared to embassies or consulate offices. Second, the territorial dispute had significant parallels to the extractive nature of the manufacturing jobs that the local residents were employed at. VSIP thus served as a localized site for larger geopolitical and territorial contests because of the presence of international investments.

Along with an influx of global investments and talent, the tech boom in Bangalore has created tensions over resource distribution. The rapid development fueled by the tech boom has exacerbated issues of infrastructure strain, environmental degradation, and socio-economic disparities, further heightening local conflicts. Consequently, while Whitefield’s emergence as a global technology hub has propelled India onto the international stage, it has also underscored the complex interplay between local aspirations and global imperatives, epitomizing the theme of localized conflict for global competition. As demonstrated by the failing infrastructure systems, ongoing water crisis and resulting protests, local residents and tech workers continue to voice their disconnect with the local ecosystem that has been created to meet global capitalism’s demands.

Golden Triangle SEZ has earned the title of the world’s worst special economic zone (Investment Monitor, 2022) for many pieces of evidence showing how the development of the area has been enabling human trafficking, drug production, as well as wildlife smuggling activities serving clients from the neighboring countries, including China but also extends to Japan and Australia as well. The expansion of unregulated gambling businesses in the area has also promoted massive fraudulent activities, money laundering, and illegal cross-border gambling deals through cryptocurrency payments. In this case, we could see how Golden Triangle SEZ’s comfortable geographical position on the border between three countries could amplify the risks of abuse of development rights. Global legal and humanitarian networks such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have been making efforts to research, document, and act towards the illegal activities conducted in the area to help victims and contain the expansion of crime networks in the area.

In the case of the Rempang Eco-city, while the project is touted to be a sustainable, environmentally friendly project, it includes a sizable industrial development of a glass manufacturing plant, Xinyi Glass. Broadly,the Rempang Eco City project can be seen as a representative of a rapidly increasing trend in urban development projects, particularly seen in countries of the Global South, that market themselves with some variation of the term “eco-city” (Nugent, 2023). However, emerging eco-cities could feature high-tech climate solutions, and yet still be deprioritizing sustainability or local ecological health. Xinyi Glass, for example, aims to utilize the locally and naturally available sand as resources for increased production of glass and solar panels. As Nugent (2023) writes, at the core many eco-cities model sustainability and can actually contain deeply unsustainable use of resources. Further, who is benefiting from these climate solutions featured in the eco-cities is also a question to be asked, especially if the process of developing them includes natural resource extraction or local indigenous displacement. If not supporting local resource conservation, sustainability, and equity, eco-cities can ultimately divert attention and resources away from real, actionable climate solutions in a time of urgent need to reduce emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change. Further, while the concept of eco-cities holds significance for addressing global and local environmental concerns in urban development, these projects also risk perpetuating greenwashing and distracting from more effective strategies for combating climate change (epevan, 2019).

Conflict Urbanism 2024- Student projects from the Spring 2024 Conflict Urbanism seminar.

Please contact Laura Kurgan with any questions or requests.

ljk33@columbia.edu

Sources

“Anti-China demonstrators shouted slogans during a rally in Ho Chi Minh City,” Getty Images, May 2014, https://archive.nytimes.com/sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/14/taiwan-concerned-over-mistaken-identity-in-vietnam-protests/

Bora, S. “Workers and residents of Whitefield take out a protest rally on Monday,” Deccan Chronicle, November 2015, https://www.deccanchronicle.com/151201/nation-current-affairs/article/whitefield-residents-hit-streets-massive-protest-against-poor

Buba, I. A. (2019). Aid, Intervention, and Neocolonial ‘Development’ in Africa. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 13(1), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1470136

Chiba, Y. “Thousands of people have protested against the plan to turn Rempang into an economic zone,” Al Jazeera, September 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/27/how-a-china-deal-put-the-homes-of-thousands-of-indonesians-at-risk

Clark, J. (2023, September 18). Rempang Eco-City. Future Southeast Asia. https://futuresoutheastasia.com/rempang-eco-city

Epavan. (2020, March 18). Over the past couple of years, there has been a healthy amount of scepticism surrounding the Eco-City in Indonesia. Medium. https://medium.com/@eshapavan26/over-the-past-couple-of-years-there-has-been-a-healthy-amount-of-scepticism-surrounding-the-7c74d97b1382

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2015). Sin City: Illegal wildlife trade in Laos’ Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone. https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-Sin-City-FINAL-med-res.pdf.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions). (n.d.). BP Batam. Retrieved April 28, 2024, from https://bpbatam.go.id/en/investment/general-questions/

Herwinda, Amalia. 2023. “The Rise of Rempang Eco City In Batam: Building Greener Futures.” Retrieved from https://balancia.co.id/the-rise-of-rempang-eco-city-in-batam-building-greener-futures/#:~:text=With%20its%20green%20roofs%2C%20energy,people%20should%20live%20in%20cities.

International Tech Park Bangalore. Capitaland. https://www.capitaland.com/en/find-a-property/global-property-listing/businesspark-industrial-logistics/international-tech-park-bangalore.html

Kuaycharoen, P., Longcharoen, L., Chotiwan, P., Sukin, K., Lao Independent Researchers. (2020). Special Economic Zones and Land Dispossession in the Mekong Region. Bangkok: Land Watch Thai. https://th.boell.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/SEZs%20%26%20Land%20Dispossession%20in%20the%20Mekong%20Region-Update.pdf.

“Lao authorities help workers rescued from the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone,” Radio Free Asia, December 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/laos/human-trafficking-12192022185054.html We welcome the re-use, republication, and distribution of original RFA content published on this website only on the condition that you credit us by including the following information: Copyright © 1998-2023, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036.

Llewellyn, A. (2023, September 21). ‘Ready to die’: Indonesia Eco-City row grows as eviction deadline looms. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/21/ready-to-die-indonesia-eco-city-row-grows-as-eviction-deadline-looms

Llewellyn, A. (n.d.). How a China deal put the homes of thousands of Indonesians at risk. Al Jazeera. Retrieved April 28, 2024, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/27/how-a-china-deal-put-the-homes-of-thousands-of-indonesians-at-risk

Malaney, M. “Women board a small motor-powered boat from Chiang Saen in Thailand to Laos,” Crisis Group, March 2023. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/stepping-south-east-asias-most-conspicuous-criminal-enclave

Mehra, A. & Lesoon, C. (2022). Sustaining Green Efforts: How Tech Parks in Bangalore Address Environmental Crises. Journal of Student Research. https://www.jsr.org/hs/index.php/path/article/view/3594

NODC. (2023). Casinos, cyber fraud and trafficking in persons for forced criminality in Southeast Asia: Policy Brief – Summary Overview. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2023/TiP_for_FC_Summary_Policy_Brief.pdf.

Nguyen, K. “Demonstrators in Ho Chi Minh City on June 10,” AFP, July 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2018-07-19/american-arrested-in-vietnam-protests-faces-seven-years-in-jail

Nirupama, V. (2015). “Save Whitefield” Protest draws over 8000 People. Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/save-whitefield-protest-draws-over-8000-people/articleshow/49981432.cms?from=mdr

Notice of Valuation of Real Assets- Asset Valuation. (2024). Capitaland. https://ir.capitalandinvest.com/news.html/id/2475445

Nugent, C. (2023, May 10). So-Called “Green” Cities Promise a Climate-Friendly Utopia. The Reality Is a Lot Messier. TIME. https://time.com/6278511/green-new-cities-climate/

“Protesters opposed to resettlement plans clashed with riot police on September 11 outside government offices in Batam,” BP Batam, September 2023,

https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/19/asia/indonesia-rempang-island-protests-chinese-factory-intl-hnk/index.html

Rempang Residents Say ‘For Generations, We’ve Lived Here and Will Die Here.’ (n.d.). Pulitzer Center. Retrieved April 28, 2024, from https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/rempang-residents-say-generations-weve-lived-here-and-will-die-here

Salma. (2023, September 26). Rempang Conflict: Land Disputes Triggered by Development Project. Universitas Gadjah Mada. https://ugm.ac.id/en/news/rempang-conflict-land-disputes-triggered-by-development-project/

Sembcorp Parks Management Pte. Vision: VSIP, The Leading Integrated Township & Industrial Park Developer in Vietnam. https://www.vsip.com.vn/uploadFiles/133321c5-b53a-4f1a-bf4e-3bab9660dfd524_12_2018.pdf

Serlet, T. (2022). “Golden Triangle: The world’s worst special economic zone” in Investment Monitor. https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/comment/golden-triangle-special-economic-zone-laos-worst/.

Sidiq, A. (2023, November 22). China in land rights battle for Rempang Island: To make way for the Rempang Eco-City project, 7,500 local inhabitants must move. Asia Times. https://asiatimes.com/2023/11/china-in-land-rights-battle-for-rempang-island/

“Territorial conflict sparks anti-China anger in Vietnam,” Reuters, May 2014, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2014/05/140514_asia_china_vietnam_ataques_nc

Webmaster. (2024, March 1). Rempang Eco-City Development: Nearly 70 Percent Completion in Model Home Construction. BNA - Breaking News in Batam and beyond: Batam News Asia. https://batamnewsasia.com/2024/03/01/rempang-eco-city-development-nearly-70-percent-completion-in-model-home-construction/