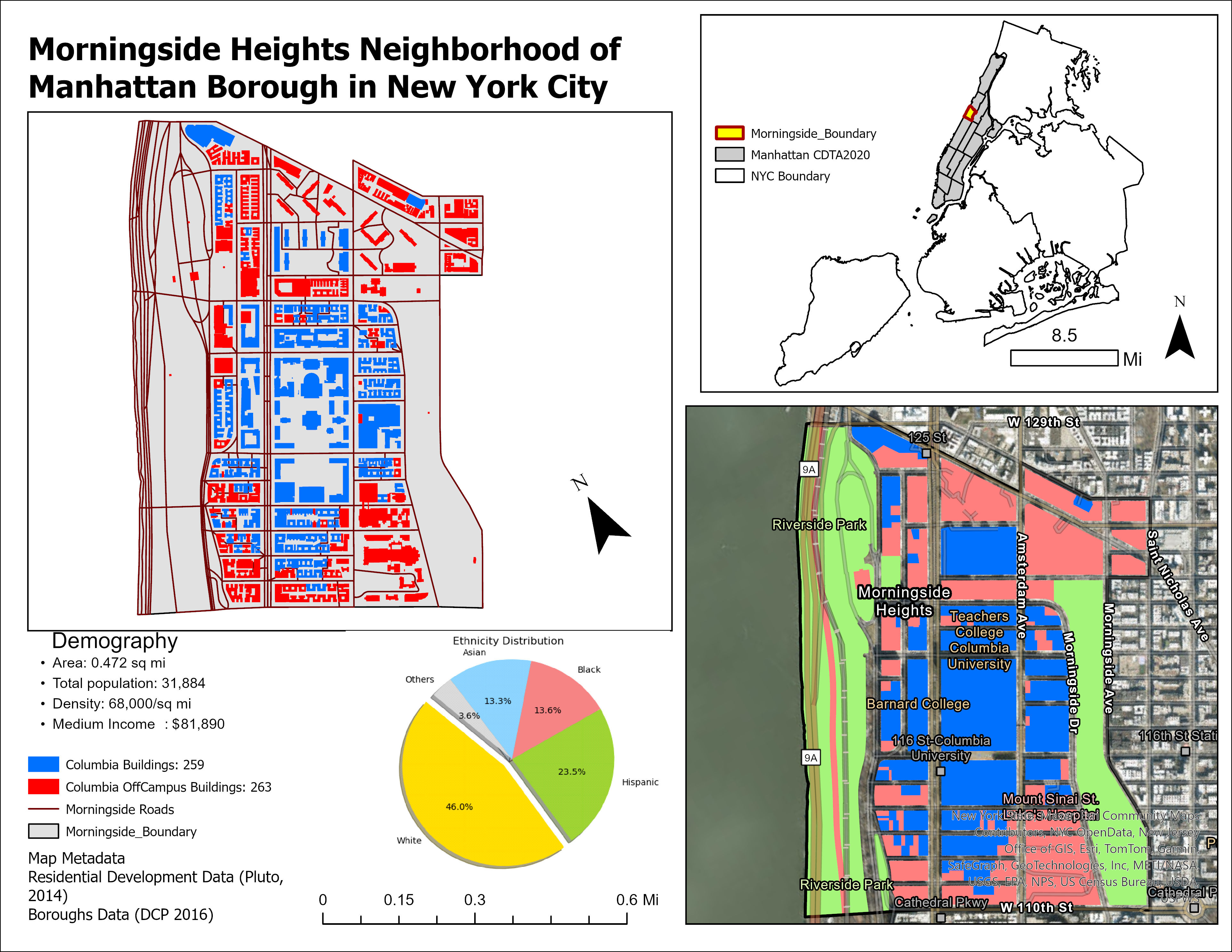

Template Post: Mapping Analysis of the Impact of Columbia University's Growth in the Morningside Heights Neighborhood: A Study on Gentrification and Residential Displacement

Introduction

The Morningside Heights neighborhood in New York City has witnessed substantial transformations attributed to urban development and institutional expansion initiatives in the post-World II era. While urban development and the proliferation of educational institutions are understood to usher in economic prospects, they frequently intersect with gentrification and housing affordability challenges, leading to the uprooting of established communities.

Columbia University’s expansion into the Morningside Heights neighborhood epitomizes conflict urbanism, where urban development catalyzes resistance to infrapolitics by manifesting and exacerbating spatial inequalities.

Historical Parts

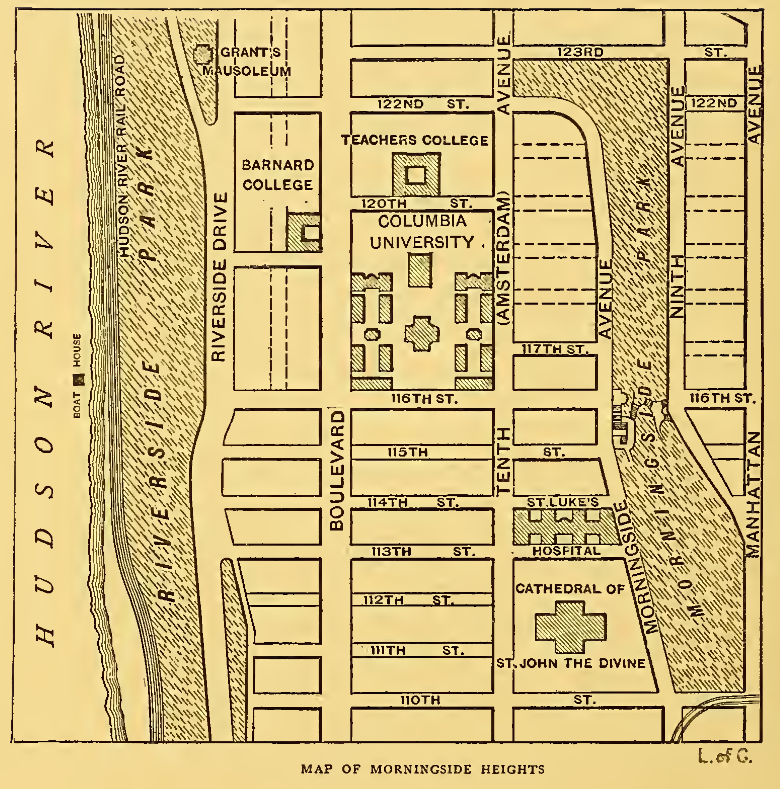

- 1816: The Society for New York Hospital started buying land;

- 1821: The Bloomingdale Asylum;

- 1843: Leake and Watts Asylum;

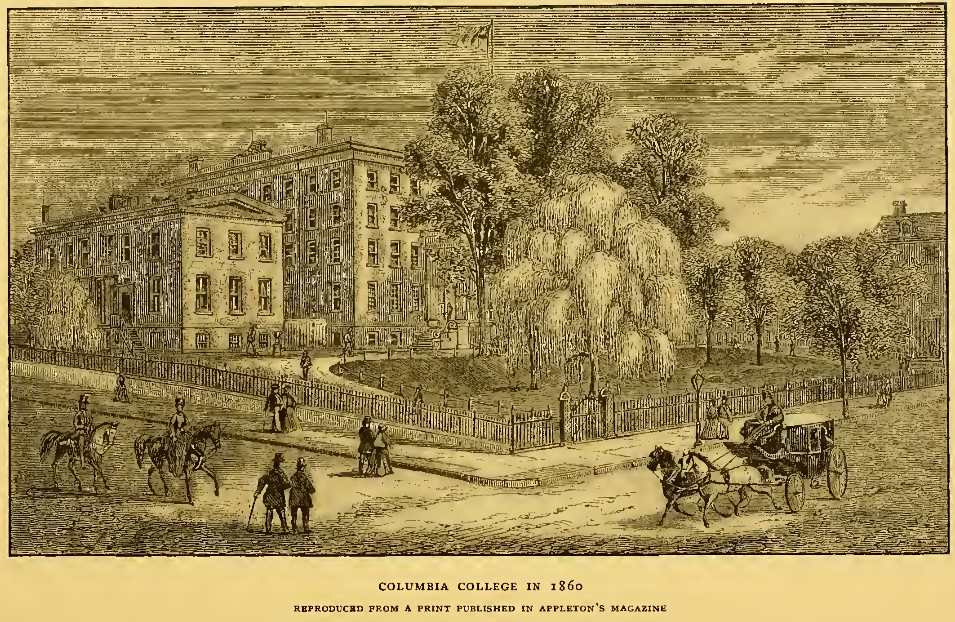

- 1880: Riverside Drive; Columbia bought Bloomingdale and the Leake &Watts Asylum campuses;

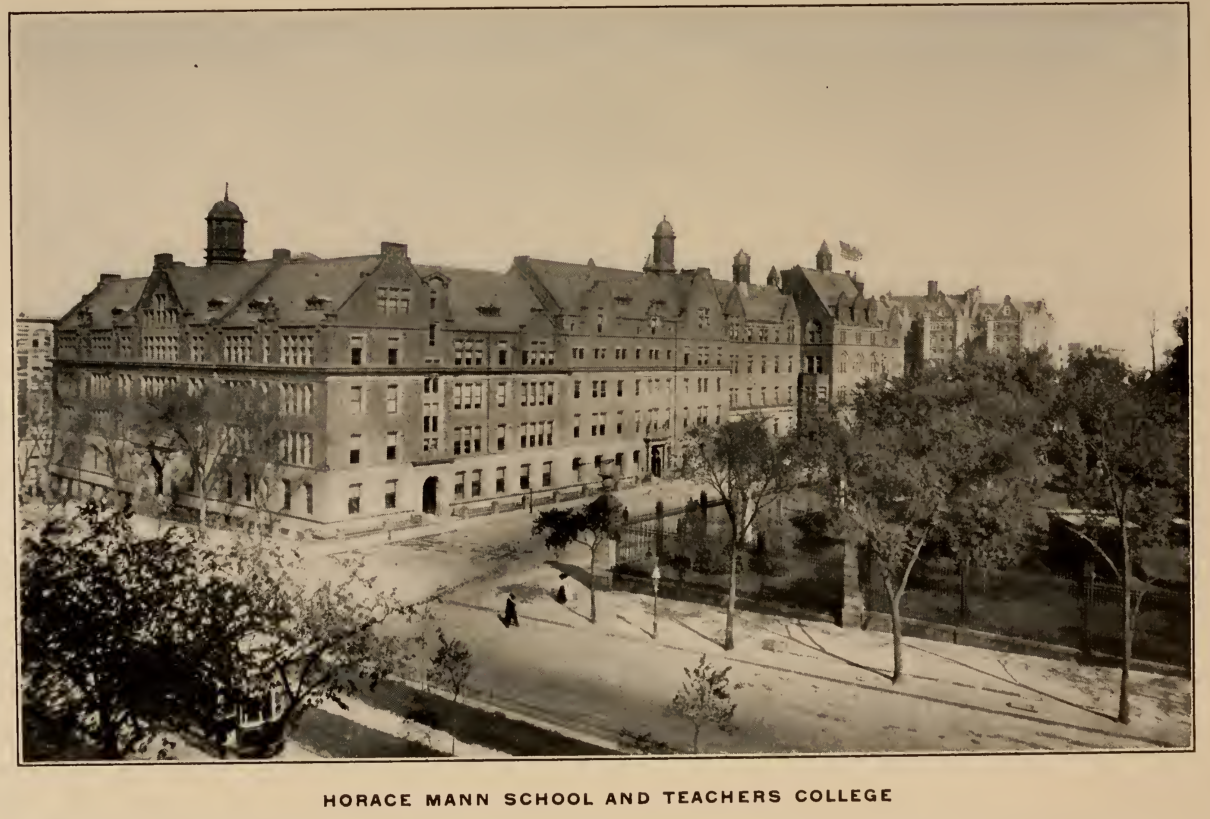

- 1895: Morningside Pak. 1887 & 1889: Teachers & Barnard College, etc.

- 1904 Subway stations 110, 116, & 125th St opened;

- 1928: Jewish & Union Theological Seminaries; Mount Sinai, and Mount Sinai St Luke’s Hospital,

- 1910: St John the Divine, etc.

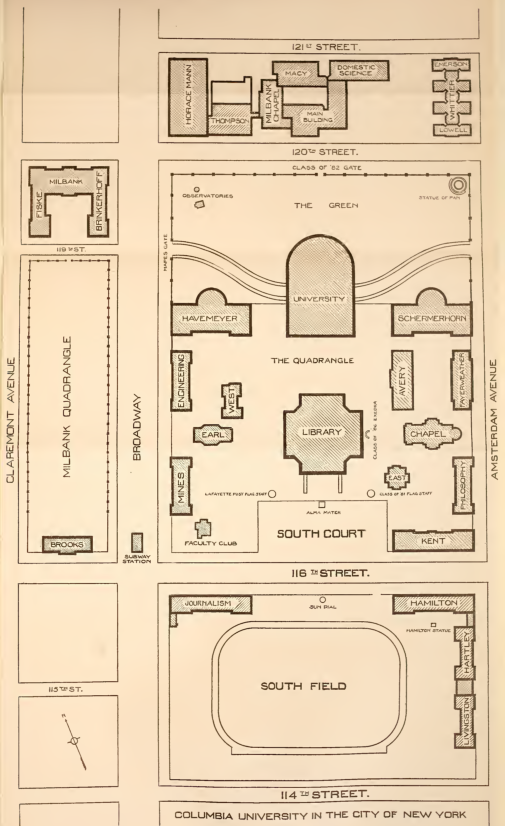

Teachers College, 1909. View looking northwest from Amsterdam Avenue and 119th Street with Columbia University’s Green in the foreground; from right, Whittier Hall, Household Arts Building (now Grace Dodge Hall), Main Hall and Macy Hall, Milbank Memorial Hall, Thompson Hall, and Horace Mann School, with Grant’s Tomb at rear left.

- 1920s:commercial ventures low-rise buildings;

- 1930: white and middle-class ( professionals like academics, engineers, doctors, lawyers, and businesspersons)

- 1930s: split between the two main groups

- 1929-1939: Great Depression.

- 1950s-1960: Columbia, Barnard College, & Other

- 1956: Grant Houses

- 1957: Morningside Gardens;

institutions purchased dozen buildings. 1970s protests against Columbia.

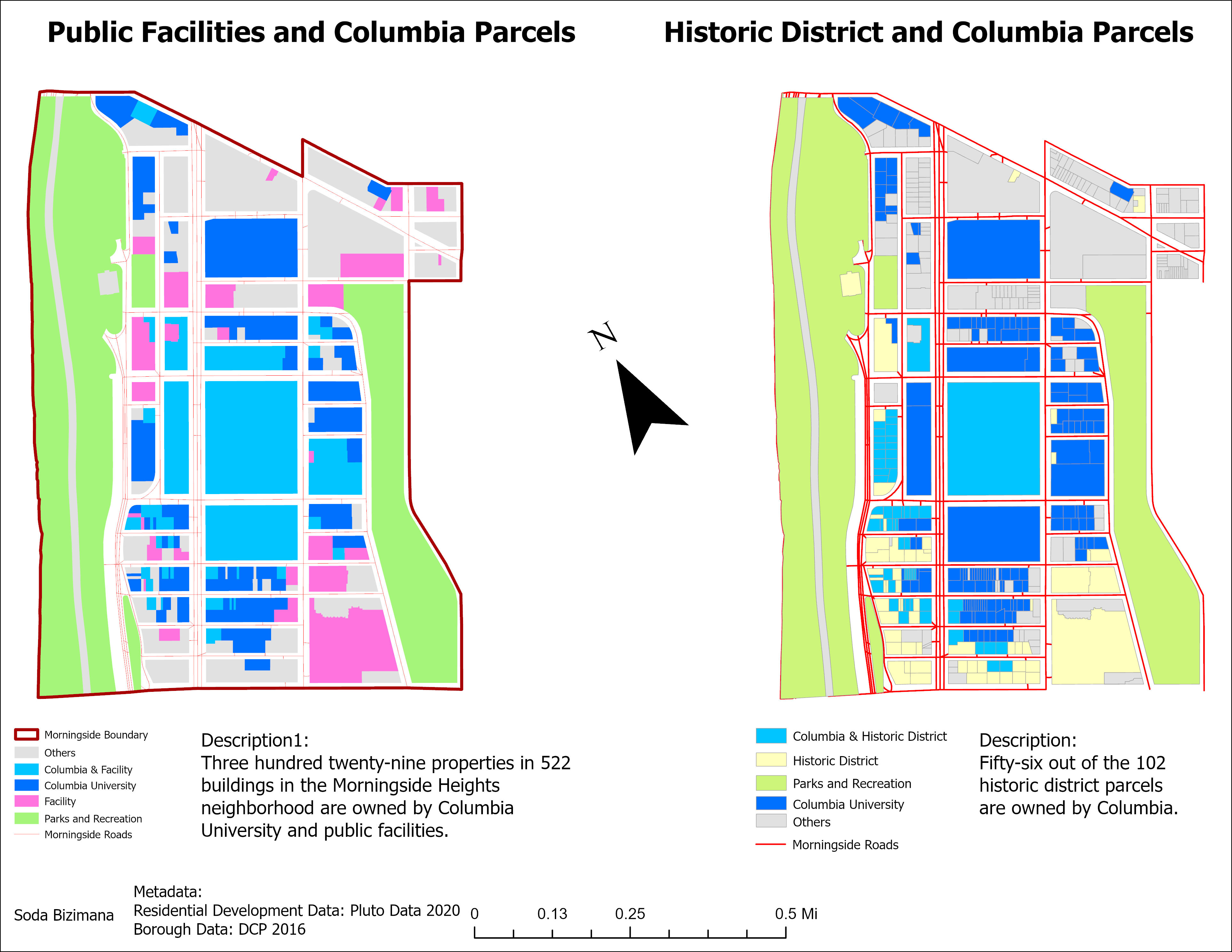

- 990s: Columbia started to restore several of its buildings. By the end of the decade only 50 apartments between 110 & 120th were not owned by Columbia.

- 1990s: businesses in the area;

- 2010s: new developments;

This process sheds light on how institution expansions contribute to the production of spatial inequalities, leading to conflicts that emerge from the displacement of long-standing communities. By altering the socio-economic landscape, such as expansion resistance, the affected communities, with their agency and resilience, play a crucial role in navigating the changing dynamics of their neighborhood, demonstrating their empowerment and resilience in the face of urban development.

Existing Situation in Morningside Heights

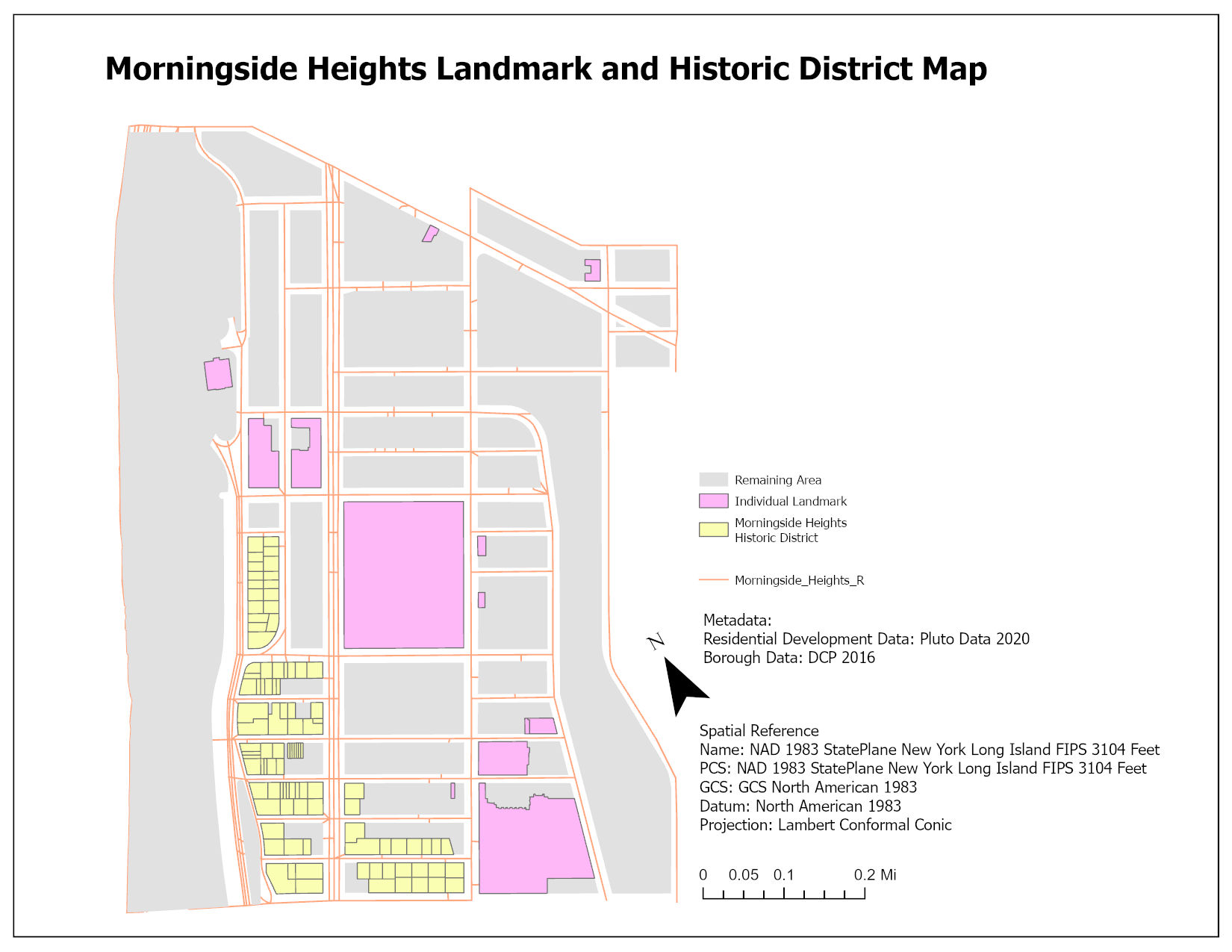

- 2017: Historic District.

- 2019: DCP declined to rezone MH;

- 2021 MHCC & Local politicians will rezone 15 blocks of MH.

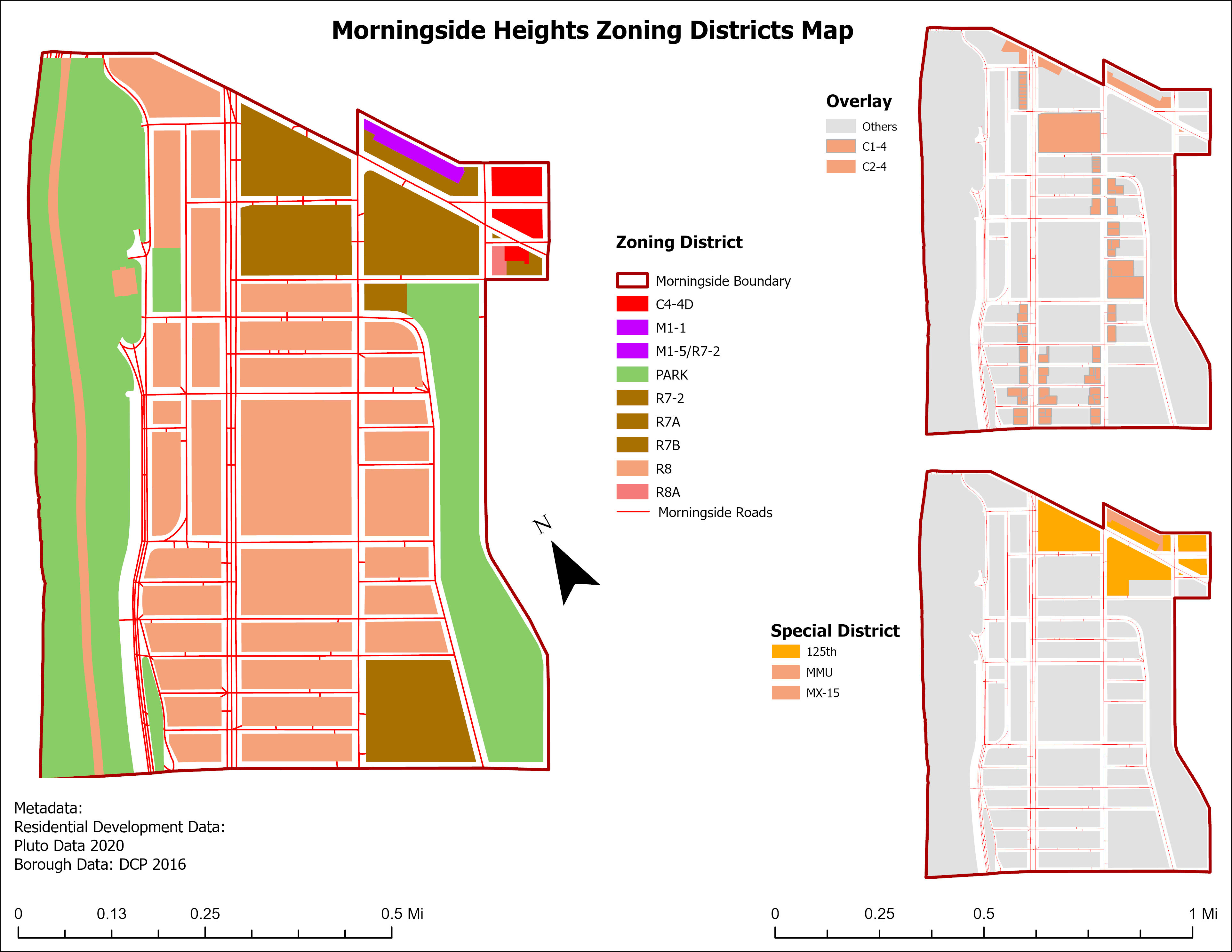

The existing zoning laws in Morningside Heights date back to 1961 and have not been updated since.

These outdated regulations allow unrestricted building heights and permit developers to create tall towers without discretionary approval.

As a result, developers have exploited these relaxed zoning laws, leading to luxury overdevelopment.

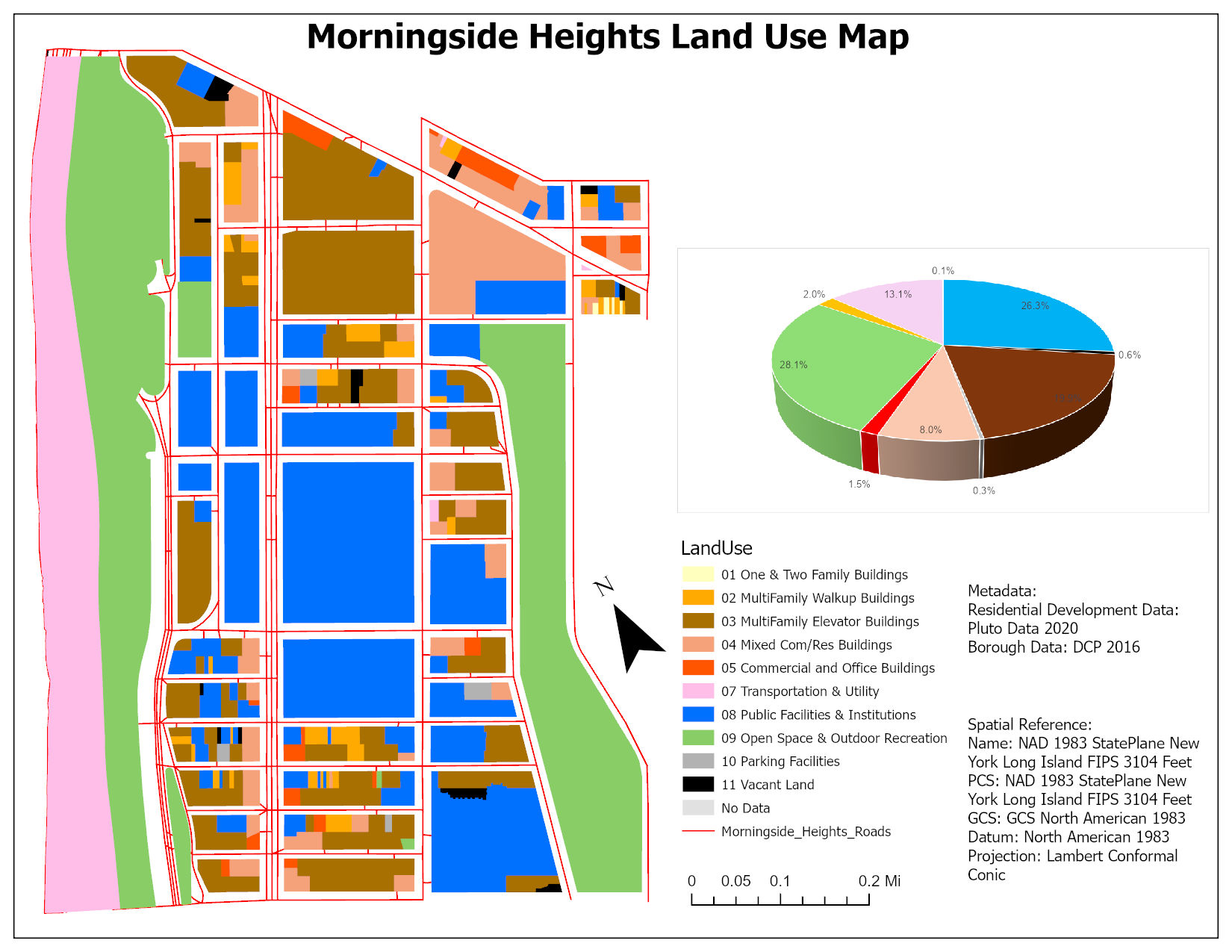

Columbia University’s expansion is a significant factor exacerbating the current housing crisis. This expansion has led to a noticeable decrease in the number of affordable housing units in the Morningside Heights neighborhood, underscoring the urgency and severity of the situation.

Spatial Inequalities

The spatial inequalities manifest in increased property values and rents, which disproportionately affect the original residents of Morningside Heights. This spatial manifestation of inequality is not merely a matter of economic disparity but also a reflection of deeper socio-political divisions, where the interests of a dominant institution override those of the local community.

Conflicts

The conflicts arising from the spatial inequalities are multifaceted, including socio-economic development, cultural erasure, and community fragmentation. These conflicts are not always overt but are embedded in the everyday experiences of residents who face the threat of displacement.

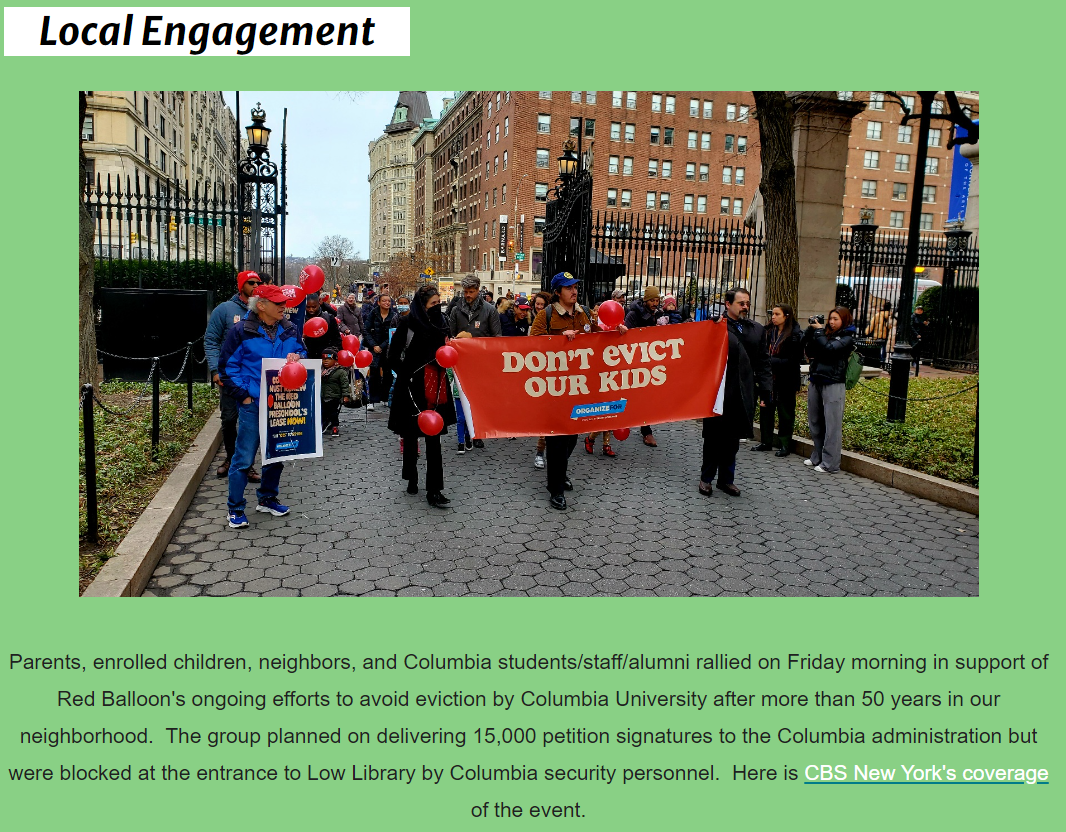

The infra-political aspects come into play as residents engage in subtle forms of resistance and negotiation, from participating in community organizations to utilizing legal avenues to challenge development projects—these forms of resistance to the spatial and socio-economic reconfiguration imposed on them.

Through MHCC Morningside Heights Residents committed to protecting and improving their neighborhood. They want to limit real estate overdevelopment, expand opportunities for affordable housing, and keep Morningside Heights neighborhood real and vibrant.

Conflicts Resolution

Engaging in participatory planning processes that genuinely incorporate the voices and needs of affected communities, ensuring that development projects are aligned with the interests of all stakeholders. Implementing policies to preserve affordable housing and protect residents from displacement, such as rent control measures, affordable housing quotas for new developments, and support for community land trusts. Fostering community-based initiatives that empower residents and support the sustainability of local economies and cultures, counteracting the homogenizing effects of gentrification.

Bibliography

-

Adams, E. & Daniel R. Garodnick. (2022). Zoning Resolution: Chapter 3. Residential Bulk Regulation in Residence Districts. The City of New York. https://zr.planning.nyc.gov

-

Albrecht, L. (2012). From Bloomingdale to SoHa: One UWS Neighborhood’s Quest for a Name. DNA Info. http://www.dnainfo.com/new-york/20120501/upper-west-side-morningside-heights/from-bloomingdale-soha-one-uws-neighborhoods-quest-for-name

-

American Community Survey. (2021). Morningside Heights, Manhattan, NY Household Income, Population & Demographics Point2. https://www.point2homes.com/US/Neighborhood/NY/Manhattan/Morningside-Heights-Demographics.html -

Dolkart, A. S. (1998). Front Matter. In Morningside Heights (pp. i–vi). Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/dolk07850.1

-

Lees, L., Slater, T., & Wyly, E. (2008). Gentrification. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203940877

-

Morningside Area Alliance. (2023, May 10). Morningside Heights Historical Timeline Through 2010. https://morningside-alliance.org/history-1980-through-2012/

-

Morningside Heights Inc. (1959). Morningside Heights. https://archive.org/details/morningsideheigh00morn

-

NYC HPD. (2019). Housing New York: A Five-Borough, Ten-Year Plan. https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/about/the-housing-plan.page

-

NYC Rent Guidelines Board. (2021). https://rentguidelinesboard.cityofnewyork.us/2021-22-apartment-loft-order-53/

- NYU Furman Center. (2021). Morningside Heights/Hamilton Neighborhood Profile.. https://furmancenter.org/stateofthecity/view/state-of-new-yorkers-and-neighborhoods-2020