Mercury Scars

Introduction: Surveying the Forest

In 1950, in line with the post-World War II technoscientific era, Brazil and the United States signed the Agreement for Special Technical Services. This agreement delineated a mutual commitment between the two nations to undertake cartographic projects in Brazil alongside a spectrum of technical cooperation initiatives(1). However, it wasn’t until 1964—following the civic-military coup that would trigger almost twenty years of U.S.-backed dictatorship in Brazil—that the first aerial survey operation began. The Inter-American Geodetic Survey (IAGS), a federal undertaking inaugurated during President Harry S. Truman’s incumbency in 1946(2), was tasked with spearheading the project on behalf of the United States. The core objective of the Inter-American Geodetic Survey (IAGS) was to facilitate cartographic mapping across the Antilles, Central, and South Americas through cooperation. Their mission was “to make the countries cartographically self-sufficient”(3) having the United States as the provider of training and technical support to local technicians and students in all phases of their mapping programs. In exchange for such support, the United States gained unfettered access to the acquired data, paving the way for the potential emergence of divergent interests and strategic maneuvering.

Image 1: The work coordinated by IAGS was executed by the 10th Air Survey Squadron Group of the United States Air Force (Aerial Squadron Team 10 – USAF – AST10). Mixed team AST10 BRAZIL-USA. Source: Photo from the personal archive of Col. Krukoski found in Mauro Pereira De Mello, Claudio João Barreto Dos Santos, and Marcelo Maranhão, “Uma Abordagem Diacrônica Sobre a Influência Da Relação Brasil-Estados Unidos No Mapeamento Do Território Brasileiro Nas Escalas Topográficas 1:50.000 e 1:100.000,” Terra Brasilis, no. 10 (December 12, 2018)

It is also important to highlight that the enlistment of scientists and technicians to collaborate with the military apparatus under the dictatorship constituted a strategy aimed at cultivating an aura of impartiality—using a rhetoric of objectivity, modernization, and efficiency—not only in the context of the nation’s modernization but also concerning the legitimization of the regime itself(4). Thus, cartography emerged as a tool for social control and narrative construction.

Image 2: RADAMBRASIL Project. Sheet SC.24-X-D., 1976. Source: ESDAC - European Commission.

As a direct consequence of this complex network, the “Radar in the Amazon” (RADAM) project emerged in the 1970s. This initiative aimed to employ side-looking airborne radar (SLAR) technology to map the entire Amazon Basin and assess its natural resources, thereby situating the region within the broader geopolitical framework. Aligned with the National Integration Program(5), which delineated the imperative of conducting surveys encompassing topography, forest cover, geomorphology for mineral exploration, energy resources, soil composition, drainage patterns, and territorial cohesion(6), the newfound radar technology was deployed by the military regime to penetrate the forest, enhancing the often inaccurate or incomplete understanding of the Amazonian terrain by non-indigenous people. The extensive presence of clouds, attributed to the region’s high atmospheric humidity and distinct meteorological dynamics, made conventional aerial photography coverage—an approach employed since 1964—impractical for conducting surveys in the Amazon. In a collaborative effort between the Brazilian National Commission for Spatial Activities and NASA, it became clear that radar technology was the best way to survey the North of Brazil and overcome the weather conditions.

Image 3: “Improvised camping of the pedology team at the Von Steiner riverbanks in Mato Grosso.”

Source: “RADAM Project Is Subject of Publications and Event at IBGE | News Agency,” Agência de Notícias - IBGE, October 30, 2018.

Image 4: “Aerial photograph of Carolina, located in the Tocantins riverbanks, during reconnaissance flights using infrared film.” Source: “RADAM Project Is Subject of Publications and Event at IBGE | News Agency,” Agência de Notícias - IBGE, October 30, 2018.

In 1975, the project changed its name to RADAMBRASIL as it expanded to encompass the entirety of the national territory. During this same year, the initiative disclosed data regarding gold, cassiterite, and uranium deposits in the Amazon region, which drew thousands of men to participate in what would later be recognized as the Brazilian “gold rush” of the twentieth century. One of the stages of this migratory and economic process occurred in Roraima, on the border with Venezuela, in an area occupied by the Yanomami people, the largest indigenous group in the country. The area constituted Sheet NA/NB.20 within RADAM.

Image 5: Keymap highlighting Sheet NA/NB.20, where the Yanomami indigenous land is located, “Map of Potential Land Use,” RADAMBRASIL Project, 1975. Source: “Boa Vista Roraima. Mapa de Uso Potencial Da Terra. Folha NA./NB.20. Volume 8. - ESDAC - European Commission”.

Image 6: Map of Potential Land Use, RADAMBRASIL Project, 1975. Source: “Boa Vista Roraima. Mapa de Uso Potencial Da Terra. Folha NA./NB.20. Volume 8. - ESDAC - European Commission”.

Images 7-9: The Serra Pelada mine was probably the most famous Brazilian “gold rush” episode, 1981. Source: Photos by Rudi Böhm found in Mídia NINJA, Ensaio • Serra Pelada 1981.

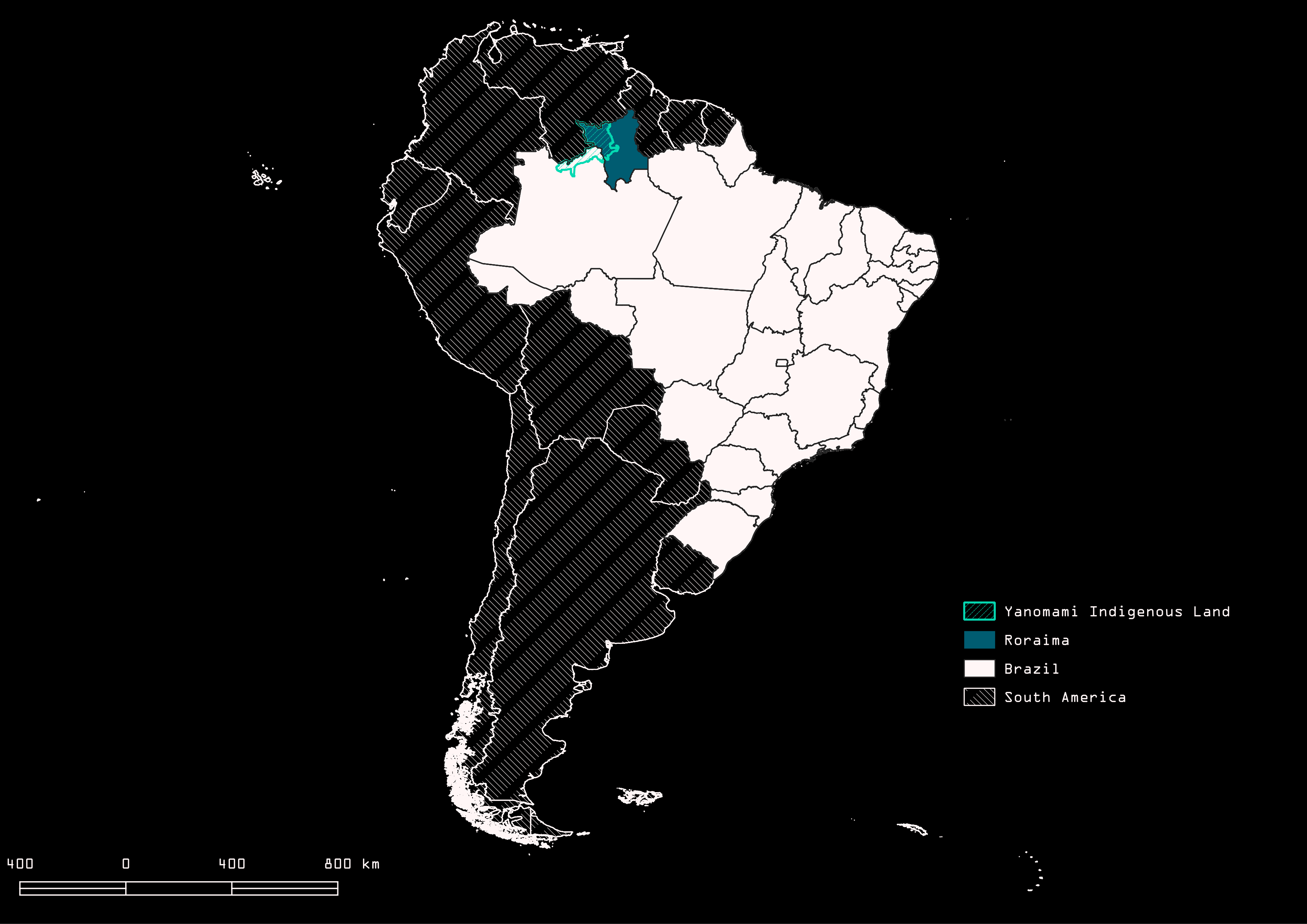

The Yanomami Indigenous territory occupies an area equivalent to the size of Portugal and has been a disputed land for many decades. It is situated at the intersection of three nations, straddling the boundaries of legality and illegality, forest and mercury, sky and earth, and, most significantly, between indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

Image 10: Map of Brazil highlighting Roraima. Source: Map created by Clarisse & Gokul using QGIS.

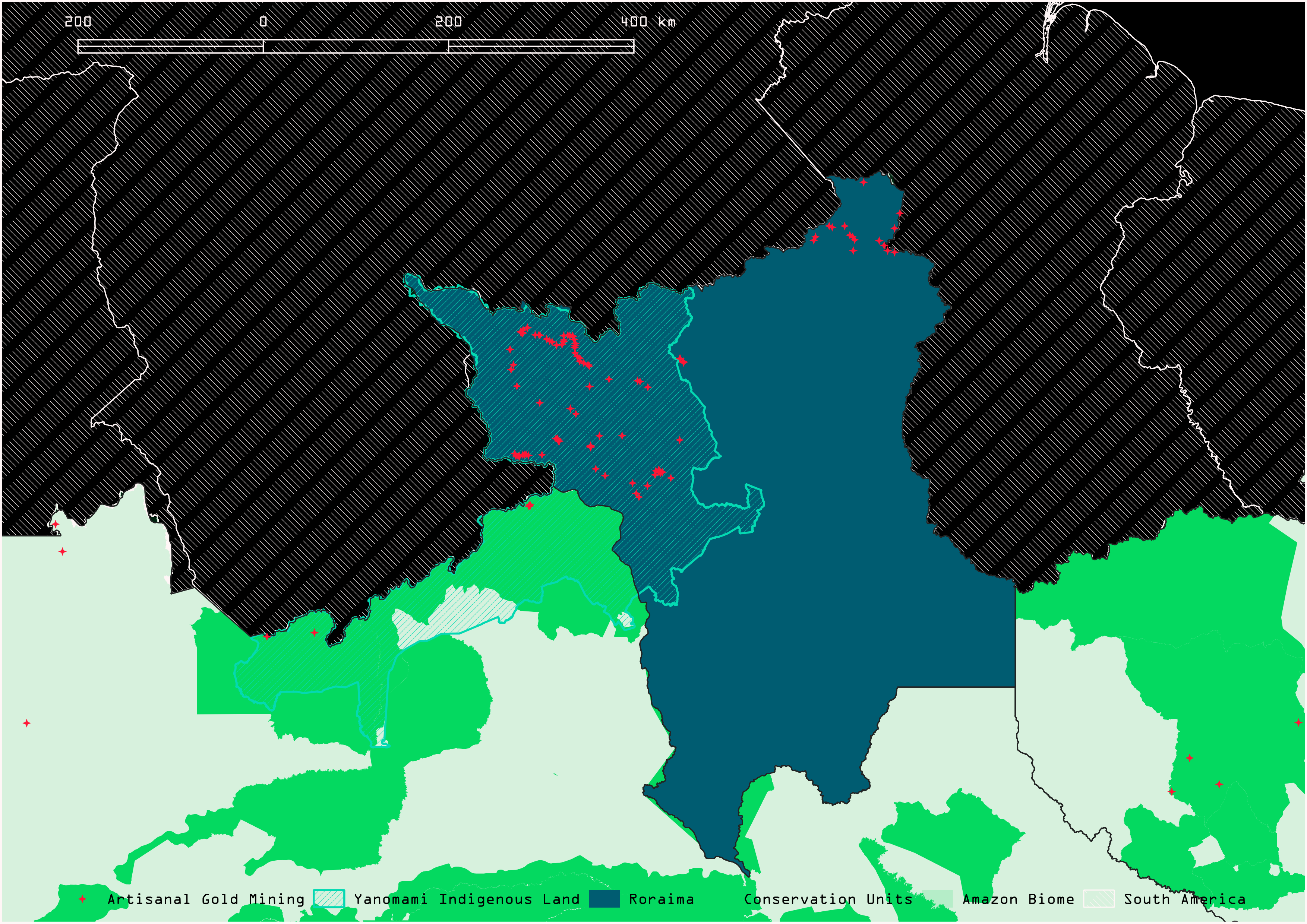

Image 11: Map of the Northwest of Brazil, highlighting Roraima, the Yanomami Indigenous Land and Conservation Units. Source:Map created by Clarisse & Gokul using QGIS.

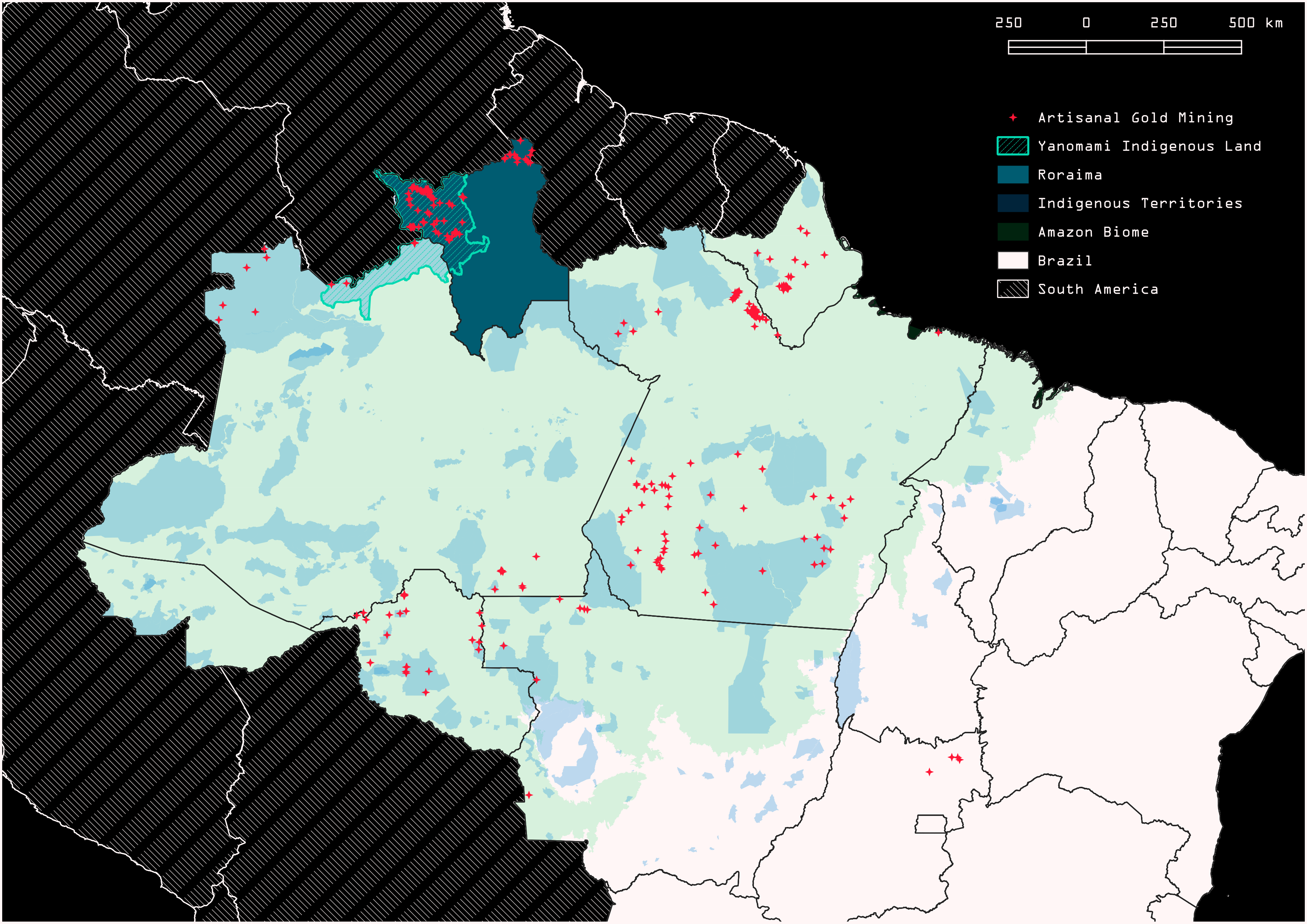

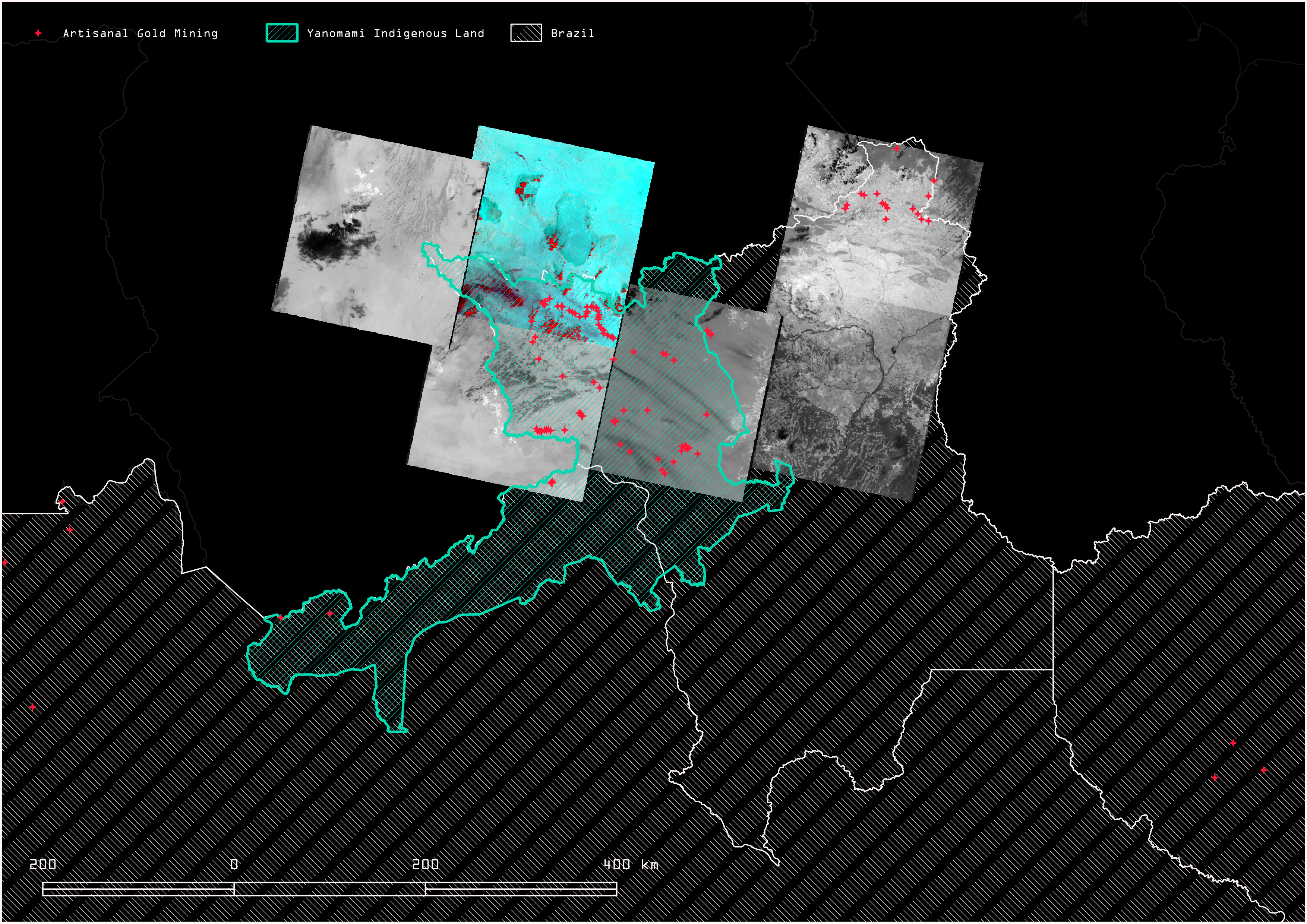

Image 12: Map of the Amazon biomel, highlighting Roraima, the Yanomami Indigenous Land and artisanal/illegal gold mining camps. Map created by Clarisse & Gokul using QGIS.

The extraction of gold and other minerals in Roraima, which intensified in the early 1980s, attracted approximately 50,000 people(7) to the territory, along with diseases that decimated part of the Yanomami population, caused displacement, and profound alterations in the landscape and local fauna. In recent years, between 2019 and 2022, during Jair Bolsonaro’s government, the Yanomami population gained international attention again due to the worsening humanitarian, sanitary, and environmental crises resulting from the increased gold mining activity in the indigenous territory. This activity has been illegal under the Brazilian Federal Constitution since 1988(8).

Image 13: “Homoxi village in the Yanomami IT.” Bruno Kelly and Emily Costa, “Como um avião do garimpo atropelou e matou um Yanomami,” Amazônia Real, August 4, 2021

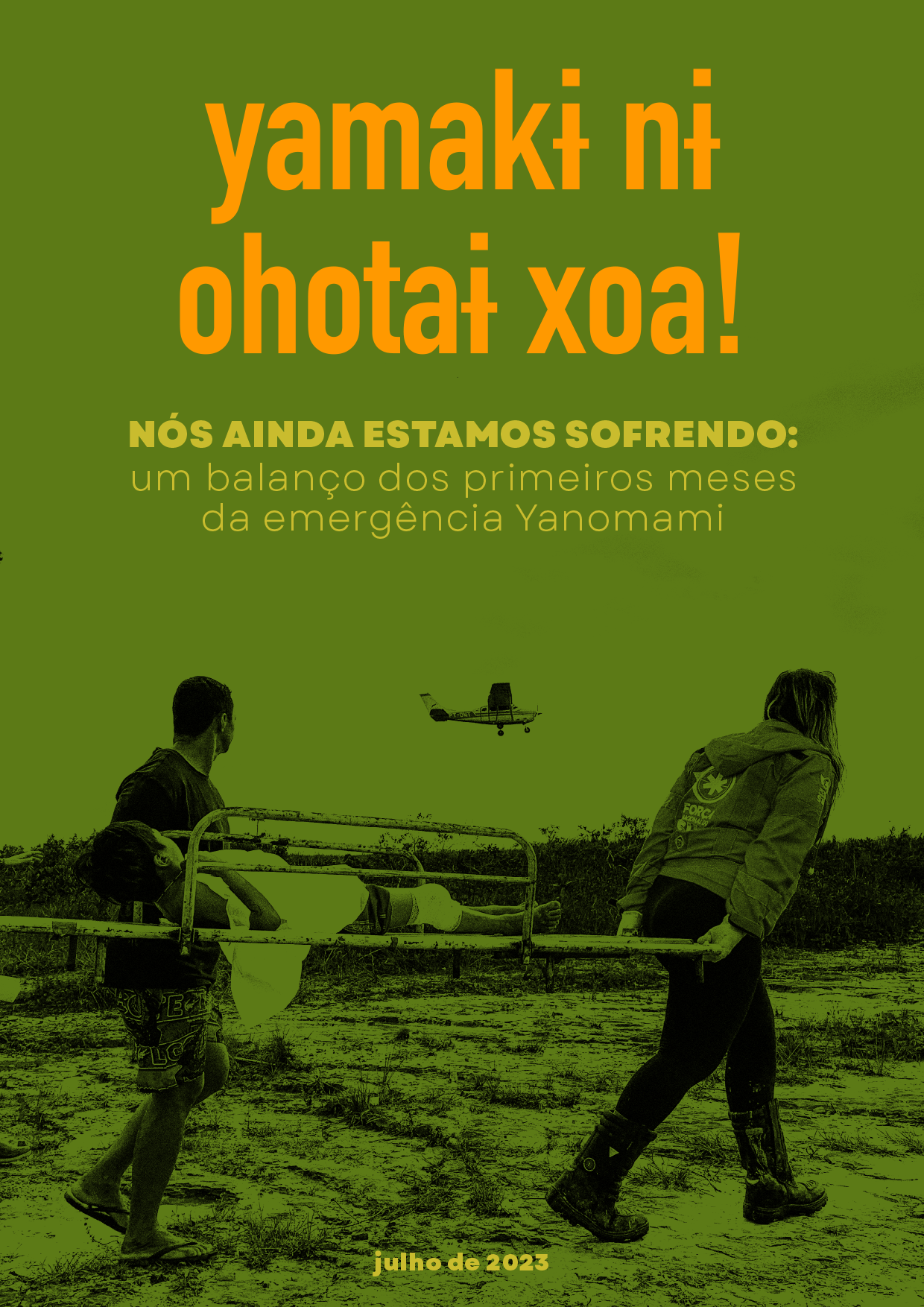

In the most recent publication produced by the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA)—a Brazilian Civil Society Organization of Public Interest that has been working alongside indigenous communities to develop solutions that protect their territories since 1994—entitled “Yamaki ni ohotai xoa! = We Still Suffer” (2023), a decline in the growth of the indigenous population was observed, something only witnessed before during the aforementioned “gold rush” between 1987 and 1990. The report highlights the direct relationship between the surge in gold mining and the increase in infectious diseases, such as malaria, influenza, pneumonia, and other respiratory infections.

Image 14: “Yamaki Ni Ohotai Xoa! = We Still Suffer: A Balance of the First Months of Yanomami Emergency.” Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) Archive.

Another piece in this puzzle concerns the use of mercury—which encompasses the title of this work—in the gold extraction process. Mercury separates gold from other sediments, generating toxic fumes and polluting rivers, animals, and humans. Notably, in a study conducted by the Federal University of Western Pará among residents of communities near mining areas, out of 400 individuals, 75% showed mercury levels in their blood exceeding the safety limit stipulated by the World Health Organization(9).

Image 15: “Garimpeiro displays mercury in his hand.” Fábio Bispo, “Da Bolívia para o Tapajós: a rota ilegal do mercúrio até chegar nos garimpos das terras Munduruku,” InfoAmazonia, Nov 30, 2022.

Bearing in mind that “cartographic map-making has played a pivotal role as a political technology of empire-building, settler colonialism, and the dispossession of Indigenous lands”(10), this work addresses one portion of the Yanomami territory through different temporalities, media and cartographies. Departing from a 1975 radar image produced within the RADAM project and shifting to a Landsat image taken this year, we can consider the impact inflicted on the forest in almost fifty years, separating both records. Shifting to the recent presence of Starlink technology in the territory, we will observe how these extractivist processes are evolving in the forest and resonating in the sky. Finally, we will arrive at YouTube videos filmed and publicly posted by illegal gold miners operating in Yanomami indigenous lands, shifting our vision and perspective to ground level.

Four Moments, Four Media

RADAM:

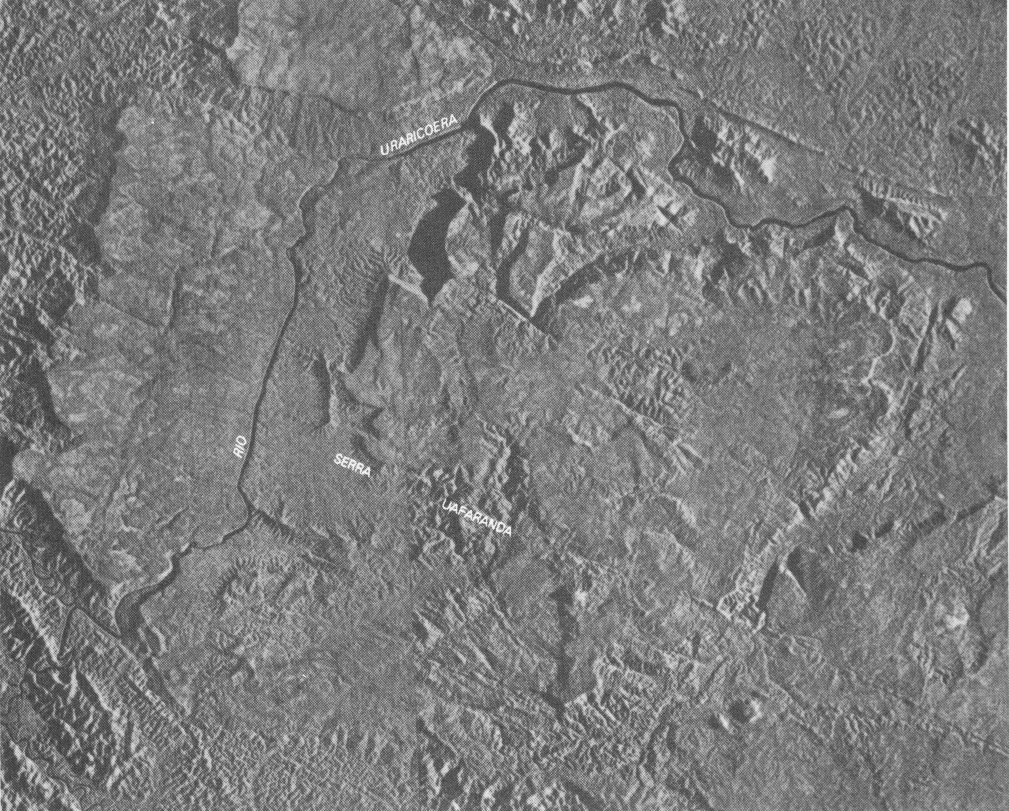

The image below populates a five-hundred-page book published by the Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy as part of the RADAMBRASIL project in 1975. This book constitutes the 8th volume of a series analyzing the RADAM findings regarding natural resources, geology, geomorphology, pedology, vegetation, and potential land use. The selected volume, housed in the library of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), focuses on Sheets NA.20 and NB.20, encompassing Roraima, the area of interest in this study. The image shows a portion of the Urariocoera River and the Uafaranda Mountain. Navigating through a matrix of satellite images of Roraima, one can easily detect signs of illegal gold mining simply by following the river courses, as artisanal and small-scale gold mining tends to occur along river banks. This 1975 image depicts evidence of the forest’s pristine nature before the uncontrolled extraction of this metal from Yanomami land.

Image 16: “Sheet NA. 20 Boa Vista and Part of Sheets NA. 21 Tumucumaque, NB. 20 Roraima and NB. 21; Geology, Geomorphology, Pedology, Vegetation, Potential Land Use / RADAMBRASIL Project,” Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) Library, volume 8, 1975.

Landsat:

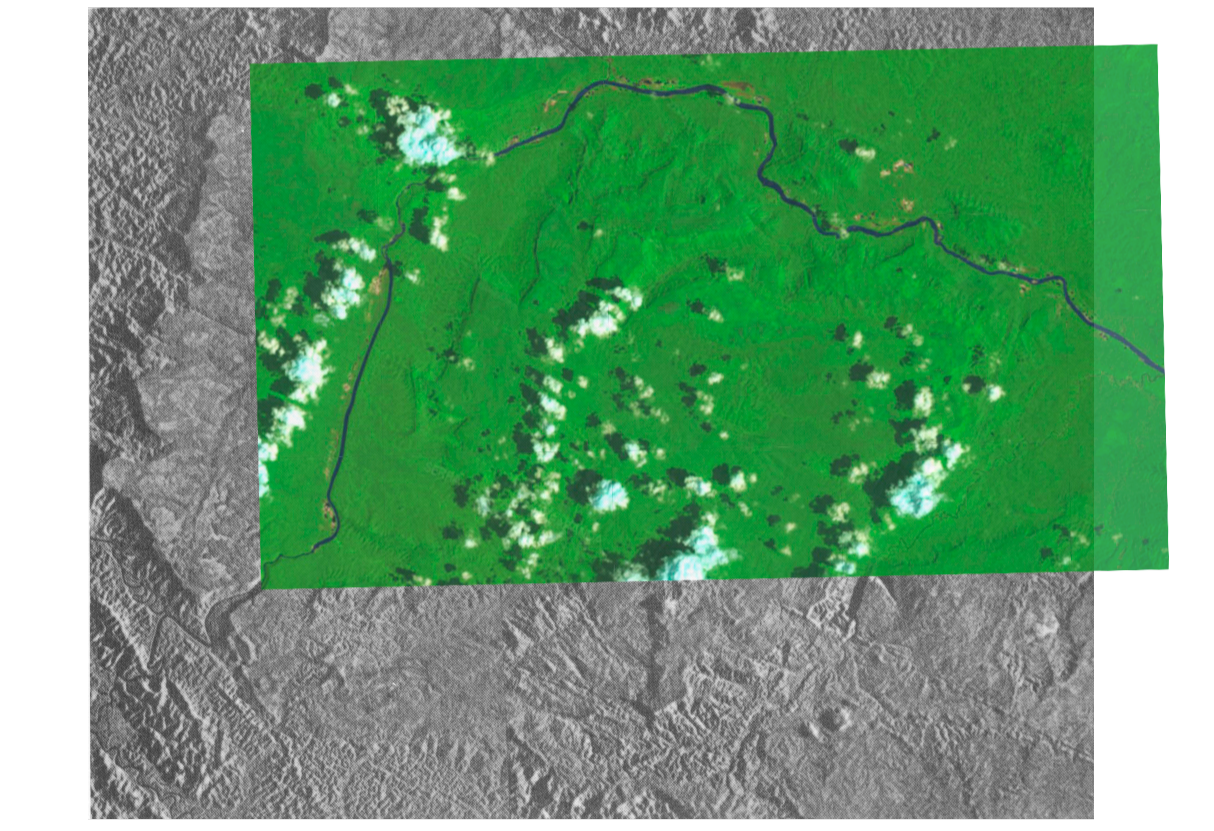

Analyzing a Landsat image from February 2024, one can discern large, amoeboid-shaped clearings amid the blue tarps enveloping the structures of the mining camps, juxtaposed against the green of the forest. These are the scars of illegal gold mining, referred to in this study as “mercury scars.” These openings not only underscore the toxicity inherent in the extraction process, disseminating mercury throughout the rivers and affecting both humans and more-than-human entities but also underscore the extent of hazardous anthropomorphic interference in the landscape of the world’s largest rainforest.

Image 17: Landsat image LC09_L1TP_001057_20240221_20240221_02_T1_refl from 04/21/2024 juxtaposed to RADAM image from 1975. (Image 16)

The Landsat is a program managed by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. It is constituted by a series of Earth-observing satellites with ground resolution and spectral bands to track and document phenomena in the landscape related to “climate change, urbanization, drought, wildfire, biomass changes”, and other natural and human-caused changes(11). Curiously, even though its archive—the world’s most extensive continuous collection of land remote sensing data—started in 1972, the oldest Landsat images we could find from our study area are from 2013.

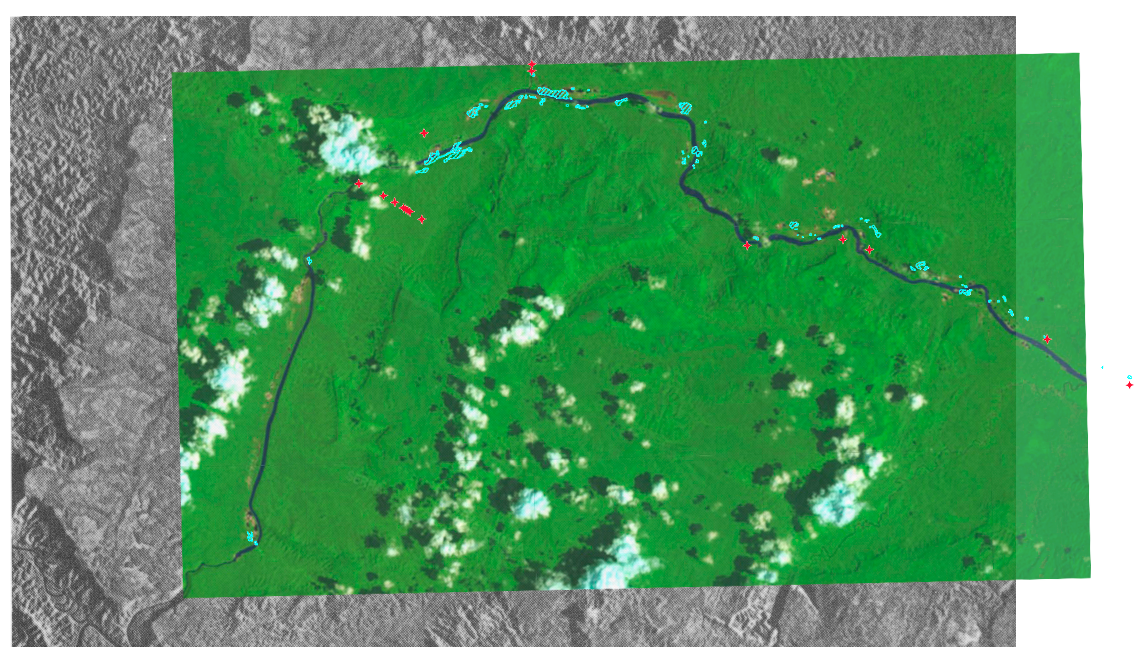

Image 18: Mining areas (highlighted in blue and red) juxtaposed to Landsat (2024) and RADAM (1975) images. Landsat created by Clarisse & Gokul.

Image 19: Landsat images over Yanomami Land and Roraima, highlighting mining areas. Maps created by Clarisse & Gokul.

Highlighted in the juxtaposition are the scars and mining camps as of 2023. At least, according to the data available through the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental (RAISG), a consortium of civil society organizations from the Amazon countries. The initiative disseminates cartographic data produced in cooperation with other projects and institutions, such as the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA). As can be perceived in the image, when combining RAISG’s 2023 data and a Landsat satellite image of this year, there is a significant increase in the number of scars along the Urariocoera River.

The Matrix: Aerial imagery highlighting Mining Scars between 2016 and 2024. Landsat images created by Clarisse & Gokul.

Starlink:

Since 2022, following an agreement between Jair Bolsonaro and Elon Musk, SpaceX has operated in Brazil “to serve schools in rural areas and monitor the Amazon rainforest.”(12) However, while only three schools have received the device so far, the use of Starlink among illegal miners has only increased, allowing for better organization, communication, and operation within the territory. This satellite internet technology enables “high-speed, low-latency internet across the globe, even in the most remote and rural locations”(13) and has been widely used in war zones, remote areas, and places hit by natural disasters as often the only way to access the internet(14).

Image 20: Bolsonaro and Elon Musk pose for a photo in SP, 2022. Source: Associated Press, “Antenas da Starlink são apreendidas em garimpo ilegal na Terra Yanomami,” G1, Mar 15, 2023.

Image 21: Equipment abandoned by miners in the Yanomami indigenous territory. A Dishy—the Starlink portable terminal—can be seen on the right. Source: Associated Press, “Antenas da Starlink são apreendidas em garimpo ilegal na Terra Yanomami,” G1, Mar 15, 2023.

Image 22: Brazilian Police Federal agents seized the internet kit in an illegal mine in 2023. Source: Associated Press, “Antenas da Starlink são apreendidas em garimpo ilegal na Terra Yanomami,” G1, Mar 15, 2023.

Video: Video of Starlink movement over the Amazon on 28 April 2024.

Roraima is, indeed, a war zone. Amidst the challenges posed by the pace of conflict facilitated by the dissemination of Dishys—the Starlink portable terminal—among mining camps, Yanomami communities have initiated the utilization of SpaceX devices to maintain real-time updates on the advancement of miners into indigenous territories, instances of fires, outbreaks of diseases such as malaria, communities facing food insecurity, water contamination hotspots (often due to mercury), as well as points of confrontation with garimpeiros(15). These data are collected and processed through an online platform named the “Map of Sanitary and Environmental Vulnerability in the Yanomami TI Regions.” This platform is regularly updated and managed by the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) in collaboration with Hutukara Yanomami Association, Seddume Ye’kwana Association, and Urihi Yanomami Association, with support from UNICEF and Nia Tero.

Youtube

Despite its illegality, garimpeiros not only openly occupy indigenous territories in search of gold but also share their day-to-day activities through YouTube and TikTok channels. In the videos, we see them hiding or confronting federal agents, walking among their flooded camps, or having fun crossing rivers and filming their pets. They burn mercury, cut down trees, and fly over the forest. In June 2023, the Federal Police claimed that there was no more illegal gold mining in the Yanomami territory. However, the latest videos posted on one of the YouTube channels are from just six months ago. Shifting away from the conventional aerial perspective provided by satellite images and maps, we offer an on-the-ground exploration of the “mercury scars” surrounding the Urariocoera River region. Through publicly available videos on YouTube, a more comprehensive understanding of this activity’s scales, tools, and organizational dynamics becomes attainable. Within some of the shared content, indigenous people are observed traversing the footage, highlighting the proximity of these activities to their villages.

This video was made using videos from the YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/@fabiogarimpojunior919/videos and a Landsat satellite image from February 2024.

Conclusion:This is Cartography

Through the selectivity of its content and its symbols and styles of representation, maps are a means of imagining, articulating, and structuring the world. Never neutral or impartial, concepts and limits cross the set of existing cartographies, and, as Melo (2011) points out, “every limit necessarily produces a frontier.” Frontiers—like the one where the Yanomami indigenous land is located—represent the unification of diverse points and the opening to another place, crossings, and interchanges. By bringing together these four moments of the same disputed territory, we weave a sort of cartography. Perhaps, more than the product created by manipulating shapefile data through QGIS or overlaying different media and formats of aerial images, this work aimed to stitch together an urgent narrative which, only by looking at it from different angles (sky and land, radar, and satellite), can we begin to understand it.

Bibliography

- Leandro Gomes Moreira Cruz and Claiton Marcio Da Silva, “The Clouds against Progress: Technoscience, Environment and the U.S./Brazil ‘Radar in Amazon Project’ (RADAM) (1970-1975),” Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies 10, no. 2 (February 18, 2022), https://doi.org/10.25160/bjbs.v10i2.128402.

- Mauro Pereira De Mello, Claudio João Barreto Dos Santos, and Marcelo Maranhão, “Uma Abordagem Diacrônica Sobre a Influência Da Relação Brasil-Estados Unidos No Mapeamento Do Território Brasileiro Nas Escalas Topográficas 1:50.000 e 1:100.000,” Terra Brasilis, no. 10 (December 12, 2018), https://doi.org/10.4000/terrabrasilis.3117.

- Mapping the Americas: Inter American Geodetic Survey (IAGS) ,National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.https://www.nga.mil/history/Mapping_the_Americas_Inter_American_Geodetic_Surve.html.

- Gomes Moreira Cruz and Da Silva, “The Clouds Against Progress,” p. 247. See also: Marcos Napolitano, 1964: História do regime militar brasileiro, (Editora Contexto, 2022).

- The National Integration Program was created by Decree-Law N°. 1106, of July 16th, 1970.

- “Pioneering, knowing, mapping: Memories of the RADAM Project/RADAMBRASIL,” book, ID: 101614, Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics Library, https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=2101614.

- James Brooke, “Boa Vista Journal; This Is El Dorado? Gold and Death in the Jungle,” The New York Times, November 30, 1989, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/30/world/boa-vista-journal-this-is-el-dorado-gold-and-death-in-the-jungle.html.

- Brazilian legislation is quite evident in stating that mining activity on indigenous lands is only allowed when carried out by the indigenous peoples themselves. Approval from the National Congress would be required in other cases.

- Heloisa Do Nascimento De Moura Meneses et al., “Mercury Contamination: A Growing Threat to Riverine and Urban Communities in the Brazilian Amazon,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5 (February 28, 2022): 2816, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052816.

- Reuben Rose-Redwood et al., “Decolonizing the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings,” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 55, no. 3 (September 2020): 151–62, https://doi.org/10.3138/cart.53.3.intro.

- What Is the Landsat Satellite Program and Why Is It Important? ,U.S. Geological Survey,” https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-landsat-satellite-program-and-why-it-important.

- Erica Saboya, “Starlink: ‘Elon Musk’s Internet’ Brings Euphoria and Fear to the Amazon,” SUMAÚMA (blog), November 6, 2023, https://sumauma.com/en/starlink-a-internet-de-elon-musk-leva-euforia-e-medo-para-a-amazonia/.

- This description appears on the home page of the Starlink website, just below where it says “ORDER STARLINK,” https://www.starlink.com/.

- Adam Satariano et al., “Elon Musk’s Unmatched Power in the Stars,” The New York Times, July 28, 2023, sec. Business, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/28/business/starlink.html.

- Garimpeiro is the term used in Brazil to refer to small-scale prospectors, typically men. The mine itself is called garimpo.

- Brian Harley, “Mapas, Saber e Poder: In Peter Gould e Antoine Bailly, « Le Pouvoir Des Cartes et La Cartographie », Paris, Antropos, 1995, p. 19-51. Traduzido Por Mônica Balestrin Nunes,” Confins, no. 5 (March 19, 2009), https://doi.org/10.4000/confins.5724.