Addis Ababa's Landmarks: Nodes of neocolonial infiltration in the capital of African independence

Grid of notable landmarks in Addis Ababa

Pride in Ethiopian culture is a precarious embodiment. It’s propped up by the narrative of being the only country in Africa that has never been colonized - a narrative that is factually untrue but socially indispensable. That narrative has been further bloated by political empires and regimes that have strived to apply colonial framings of modernity and civilization onto native vernaculars, creating ideological and emotional distances between power, people, and the city. Goals conflating modernity with civility can be traced from the “founding” of Addis Ababa as the capital city of Ethiopia in the late 1800s, to Le Corbusier’s 1936 plan for Addis Ababa in which he drew not from experience but the allure of a tabula rasa for his portfolio and the fascist movement, to Emperor Haile Selassie’s intense desire for respect on the stage of international diplomacy, to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s globalist understanding of prosperity. With each of these examples there are foreign cultural impositions or material contributions that have sneakily shaped the way Ethiopians and diaspora have grown to perceive and navigate their social, political, and built spaces.

Such impositions have made themselves explicit through landmarks all over Addis Ababa in modern and contemporary architectural styles. Nearly all landmarks, whether or not they have functional uses, share characteristics of being starkly modern in design or staunchly political. To get around Ethiopia or give directions, one must give a descriptor of the neighborhood, the intersection, and the closest landmark. Natives and diaspora actively rely on these often-foreign morphologies to define their spatial perception of the city, and of home. Landmarks as manifestations of modernity, which can be read as forms of “erasure and reinscription” (Zeleke 2010), have worked to quiet national anxieties around backwardness and incivility which have brewed since Ethiopia’s brush with colonization between 1936 and 1941. Anxieties which governments have weaponized in the country’s push towards globalization.

This research positions, tracks, and explores landmarks as urban devices of tension between the dual welcome and refusal of foreign influence upon Ethiopian identity.

Why Landmarks?

Landmarks and monuments in Addis Ababa are critical tools to navigate and situate oneself in the city. Neighborhoods are imprecise, street names change, but landmarks remain. From regime to regime there is hardly a political or social habit of tearing down landmarks, even if dedicated to the bloodiest of dictators. Landmarks are so important in Addis Ababa that they have become the defining characteristic of micro-neighborhoods that clutter the city.

Landmarks are most notably tied to political victories and losses, becoming physical reminders of the nation’s earned right of independence and belief in cultural exceptionalism. Many are also, seemingly, random, manifesting as gas stations, banks, or electric buildings. The defining feature that graduates a landmark from a statue or building to a navigation device is the depth of contrast that the design imparts upon the city’s landscape and residents’ reservoir of collective memory. Though some landmarks have been built by the hands of Ethiopian labor, many of these contrasting designs are the products of international thought, generating a cognitive dissonance between form, authorship, and the materiality of national symbolism.

This research identifies two primary landmarks of interest - Africa Hall and the African Union Conference Center - as nodes of understanding and perceiving political and cultural space in Addis Ababa and as catalytic moments encouraging non-native urban development.

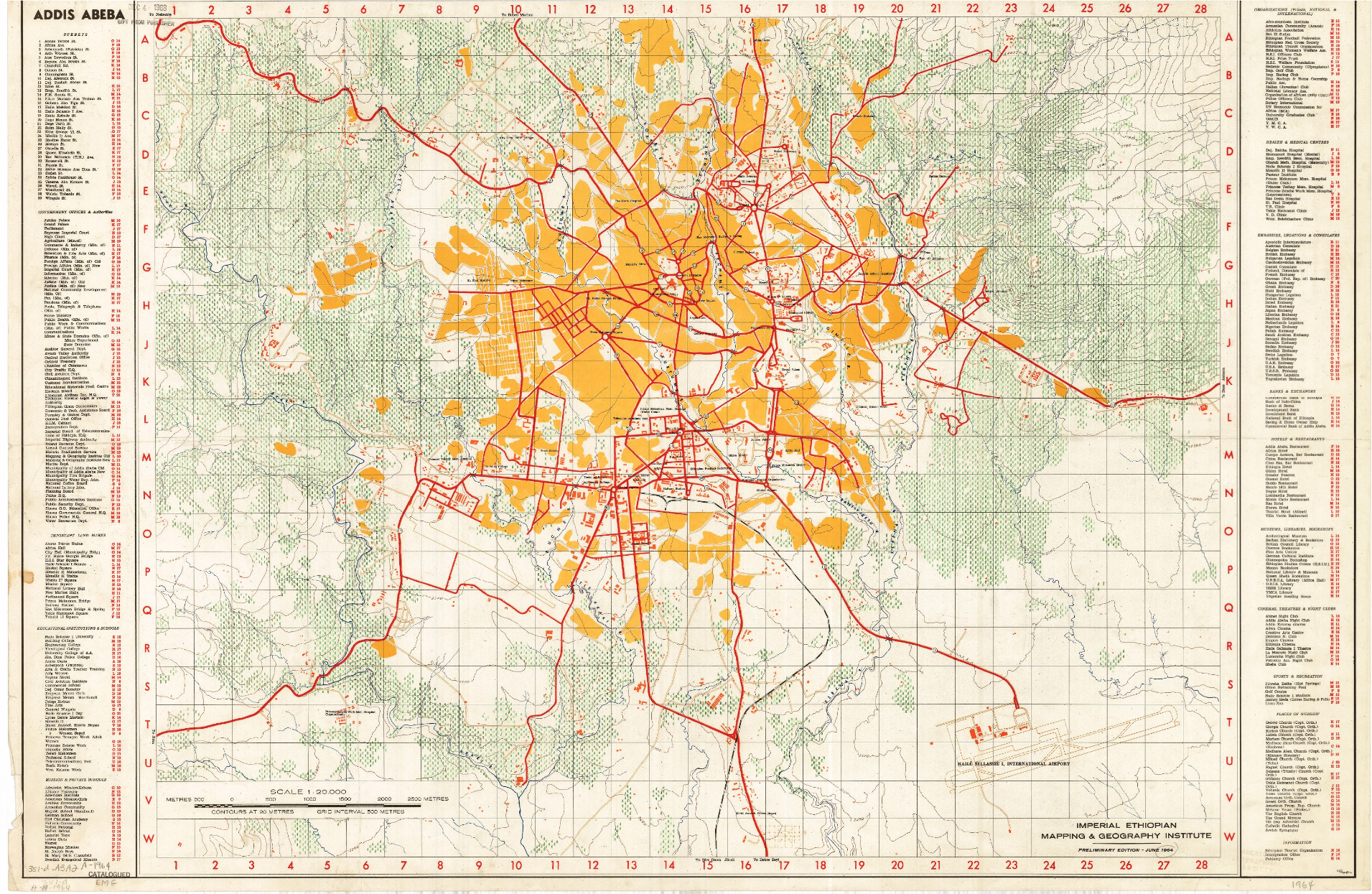

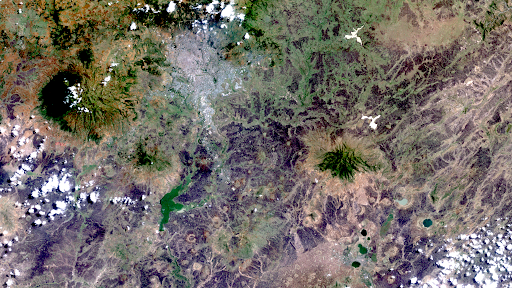

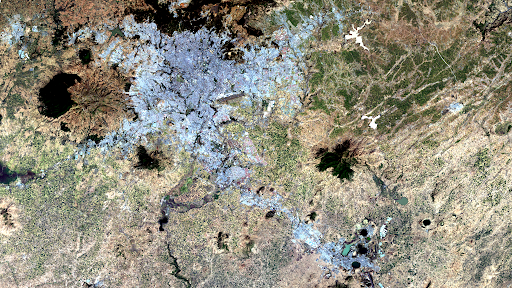

(The growth of Addis Ababa has been characterized by Western adaption to axial planning that’s succumbed to informal development, the outcome being explosive longitudinal development with latitudinal growth following commmon transit ways. The following images show incredible change in Addis Ababa’s build up (land with visible roof coverage))

1964

1990

2022

Africa Hall, Kazanchis

Kazanchis, a neighborhood bordering east of Addis Ababa’s three imperial palaces, is rumored to have roots in the Italian word for home, casa, but was more likely named after Italian construction company, Kazabi.N.C.E.S. During the Italian occupation, the neighborhood was designated as a segregated space for white Italian, highly ranked officials and became a playground for their entertainment. It was here where Emperor Haile Selassie, cognizant of this history, decided to build the first home for the Organization of African Unity (OAU), predecessor of the African Union (AU) upon his return to power.

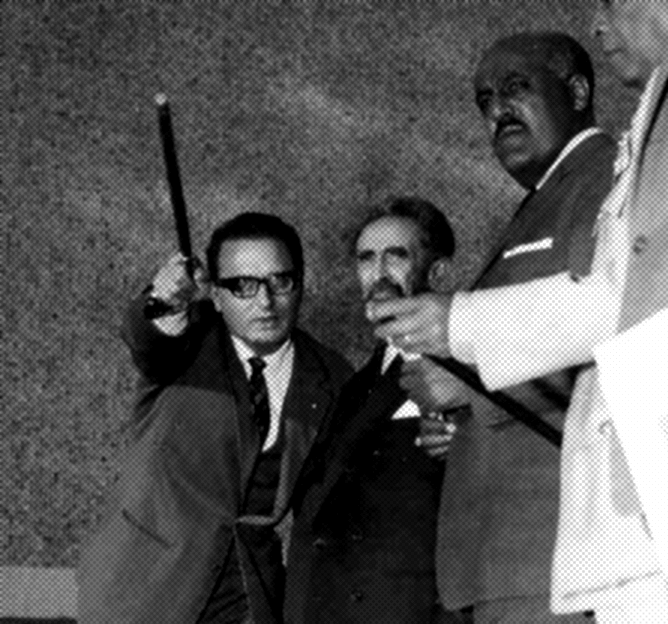

Africa Hall was the monumental structure of Haile Selassie’s dreams; imagined as soon as it was decided that the OAU headquarters would be in Addis Ababa at a 1955 Cairo meeting. Within the span of 4 years Haile Selassie launched an international design competition to show “people that it is possible to construct grand buildings here too,” stimulate investment, and “make this ‘great village’ a city and a true great capital.” Ultimately, Selassie scrapped the submission ideas in favor of Arturo Mezzedimi’s interpretation. Mezzedimi was an Italian expatriate raised in Eritrea and slowly building a body of work in both countries. Mezzedimi’s charge of Africa Hall was his big break, the launching pad for his appointment as Addis Ababa’s chief architect realizing over 100 buildings and site plans, and it grounded his 23-year working relationship with Haile Selassie. (Mezzedimi 1992).

Arturo Mezzedimi showing Emperor Haile Selassie the construction of Africa Hall, alongside former Viceroy to Eritrea Aserate Kassa

The design intent of Africa Hall was to mold a European typology with indigenous materials. However, it’s understood that less than 50% of native Ethiopian materials were used due to construction expediting. Regardless, Africa Hall’s inauguration heralded a wave of foriegn modernism; the city becoming augmented by architects from Israel (Zalman Enav), France (Henri Chomette), and the Czech Republic (Kosek Ivo). Altogether forming an architectural landscape that was both transformational and invasive. 51 years later, the negotiation of cultural and political autonomy continued through the construction of the African Union Conference Center (AUCC) in 2012. And so began the chain of monumental landmark precedents - the measure of Ethiopian political achievement becoming Africa’s largest, tallest, and brightest.

Africa Hall shortly after it was completed in 1960, source: Archivio Privato Mezzedimi

Africa Hall in the 21st century, it is currently undergoing renovation, source: Google Images

The African Union Conference Center, Mekanisa, and an Ushering in of New Dynamics of Influence

You can begin to understand the cultural ties residents of Addis Ababa have to the city’s landmarks through the Old Airport or Mekanisa neighborhood. Old Airport is more commonplace, but what one calls it may shift depending on your or your family’s relationship to its history. Old Airport was the site of Addis Ababa’s literal last airport, Lideta (which became the namesake for the micro neighborhood just north of Mekanisa. The former compound of Lideta is the current home of the Ministry of Defense, a state-of-art compound completed in 2022. On-the-ground accounts do not convey the compound as a welcoming place, although the Ministry made sure to release a quaintly soundscaped advertisement in which Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed states his hopes for the compound to be a place where families roam through the gardens.

In Old Airport sits the People’s Republic of China’s $200 million USD gift to the continent of Africa, the African Union Conference Center, designed by architects at Tongji University in Shanghai and constructed by China State Construction Engineering, to promote the image of excellency and modernity for the African Union and maintain its objective of “ridding the continent of vestiges of colonization and apartheid, to promote unity and solidarity amongst African States.” Although, the site’s predecessor, the notoriously inhumane Kerchele prison is attached to stories of political prisoners escaping to the OAU in search of amnesty. Those stories end with the escaped prisoners being ignored and returned so as to not violate the sworn neutrality of African Union members. The decision to construct the newest AU headquarters on the former grounds of Kerchele is criticized by survivors, particularly for the lack of acknowledgement or memorial. The new building’s shining, rounded glass facade reflects the future prosperity of the country, turning its face away the past, opening its arms to the free market world.

Kerchele in 2004 before demolition, source: Google Earth Pro

The African Union Conference Center today, source: Google Earth Pro

The following map offers an exploratory platform to navigate the sites of the AUCC, Africa Hall, and surrounding landmarks that inform the navigation of Old Airport and Kazanchis.

We conducted research on 34 notable landmarks between the two neighborhoods and nodes of focus, tracing their contemporary histories, architectural influences, and financial conflicts of interest. The clustering of landmarks around and between Africa Hall and the AUCC loosely follows the pattern of palace-centered axial development which characterized Addis Ababa’s urban growth up until the the fall of the last empire under the reign of Haile Selassie (Tufa 2008). The pattern has been blurred by the informal development that upticks in times of conflict. The intermingling of imposed structural form and informality have contributed to the prevalence of these landmark-named micro-neighborhoods throughout the city.

To support the map and add color to the story of landmark development and on-the-ground experiencing we developed an image repository. The repository includes additional landmarks constructed along modernist design principles and those that emerged from the so-called new style of Ethiopian modernism. Though Ethiopian modernism can be categorized as a more confused style than seamlessly hybridized (Zeleke 2010). It is our hope that the repository, which is currently private, feeds into ongoing research on Addis Ababa’s morphology.

Examples of urban landmarks existing in the repository: Ras Hotel in its 1960s glory (left), and in recent years (right), source: Pinterest, Google Images

Methodology

This project utilized an intersectional array of research methods and data analysis tools. Such methods included first-person research, oral history, analysis of satellite imagery, archival image and map sourcing, and GIS analyses such as georeferencing. These methods have been stitched together to attempt to paint a detailed picture of the landmark-ification of Addis Ababa as an urban device of foreign influence.

Though we acknowledge that the picture is not complete, is not without bias, and has not been without challenges. We experienced limitations to archival material access, available data, and available aerial imagery. Political volatility since 1975 has halted consistency with institutional data collection, and a lack of stable technology and power in Addis Ababa have stunted archiving and data collection advancements. Further, as students of spatial-based practices we recognize a practice-wide inclination to objectify the environment around us and transfigure spaces to become fascinating. Such bias emulates a top-down perspective we’ve been critical of in this work.

Throughout the research we questioned the neutrality of archival images and maps of mid-20th century Ethiopia that exist, largely, through the lens of Italian governmental agencies, Italian expatriates, or American governmental agencies. Thus lacing historical documentation, and holding hostage the historization of growth and progress with colonial biases. Which, we, and many Ethiopian nationals engaged in overlapping research, have had no choice but to integrate. These challenges necessitated a flexible and holistic approach to data collection and analysis, and personal implication of our positions and backgrounds in the work.

How does one navigate a city using landmarks when the landmarks themselves and the representations of landmarks are confused?

That question remains and keeps this research open to being part of a much larger project. Landmarks offered this research a lens on historical consistencies. Despite stark shifts in regimes and sociopolitical ideologies there has been a reliable focus on the civilized and modern image making of Addis Ababa and the Ethiopian people; so much so that it has overshadowed, and in turn disoriented the attachment one makes to a place. It’s not entirely about the landmark, about the grandeur of a building, or about the architect. The continuing research is about politicizing the culture of space and how one either grasps onto or reforms identity in the midst of spatial, cultural, and political tumult. As is the environment in Ethiopia today.

Atsede Assayehgen, Steven Duncan,

M.S. Urban Planning, Columbia GSAPP

References

Antonsich, Marco. “Signs of Power: Fascist Urban Iconographies in Ethiopia (1930s–1940s).” GeoJournal, vol. 52, Dec. 2000, pp. 325–38, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014397002570.

de Waal, Alex, and Rachel Ibreck. “Alem Bekagn: The African Union’s Accidental Human Rights Memorial.” African Affairs, vol. 112, no. 447, 2013, pp. 191–215. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43817186.

Galli, Jacopo. “Aspirations and Contradictions in Shaping a Cosmopolitan Africa: Arturo Mezzedimi in Imperial Ethiopia.” ABE Journal, no. 9–10, July 2016. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.4000/abe.10930.

Jinollo, Girmachew Tariku, et al. “Spatial Distribution of Urban Land-Use in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.” Urban, Planning and Transport Research, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2024, p. 2307364. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2024.2307364.

Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 42, no. 1, Oct. 2013, pp. 327–43. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

Léo Noyer Duplaix. Henri Chomette: Africa as a Terrain of Architectural Freedom. dir. Manuel Herz, Ingrid Schröder et Hans Focketynz. African Modernism: Architecture of Independence, Park Books, p. 271-281, 2015. Ffhalshs-01352037ff.

Levin, Ayala. “Haile Selassie’s Imperial Modernity: Expatriate Architects and the Shaping of Addis Ababa.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 75, no. 4, 2016, pp. 447–68. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26418940.

Mezzedimi, Arturo. “Testimonies Arturo Mezzedimi: Hailé Selassié: A Testimony for Reappraisal.” Apr. 1992. Archivio Privato Mezzedimi, Mezz Group.

Nyssen, Jan; Debever, Martijn; Gebremeskel, Gezahegne; De Wit, Bart; Hadgu, Kiros Meles; De Vriese, Steven; Verbeurgt, Jeffrey; Mohammed, Sultan; Frankl, Amaury; Besha, Tulu; Kropáček, Jan; Forceville, Astrid; Demissie, Biadgilgn (2020): Aerial photographs of Ethiopia 1935-1941 [dataset]. Department of Geography, Ghent University, PANGAEA, https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.920077.

Nyssen, J., Petrie, G., Sultan Mohamed, Gezahegne Gebremeskel, Stal, C., Seghers, V., Debever, M., Kiros Meles Hadgu, Billi, P., Mitiku Haile, De Maeyer, Ph., Frankl, A., 2016. Recovery of the historical aerial photographs of Ethiopia in the 1930s. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 17: 170-178.

Tufa, Dandena. “Historical Development of Addis Ababa: Plans and Realities.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies, vol. 41, no. 1/2, 2008, pp. 27–59. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41967609.

Weldegebriel, Amanuel, et al. “Spatial Analysis of Intra-Urban Land Use Dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Addis Ababa (Ethiopia).” Urban Science, vol. 5, no. 3, Aug. 2021, p. 57. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5030057.

Weldegebriel, Amanuel Tadesse, et al. “Socio-Spatial Analysis of Regime Shifts in Addis Ababa’s Urbanisation.” Applied Geography, vol. 154, May 2023, p. 102918. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2023.102918.

Zeleke, Elleni Centime. “Addis Ababa as Modernist Ruin.” Callaloo, vol. 33, no. 1, 2010, pp. 117–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40732799.

Zeleke, E. Centime. Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production, 1964-2016. Brill, 2020.