COVID-19 and Water Rights On the Navajo Nation

Stay at home order near Many Farms, Arizona on the Navajo Nation. From NBC News.

Stay at home order near Many Farms, Arizona on the Navajo Nation. From NBC News.

Introduction

In mid-March of 2020, around the time that the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 a pandemic and the United States had claimed it a national emergency, hotspots began to emerge throughout the country as the virus took hold with particular intensity in specific regions. Many of these were urban areas with high density, cities like Seattle and then New York, Detroit, and suburban New Jersey. One hotspot however seemed to surprise both the public and public health officials: the Navajo Nation, a Native American reservation that spans northern Arizona, southern Utah, and northern New Mexico. In April cases on the Navajo Nation started rapidly climbing, by May 18, it had surpassed New York for highest cases per capita.1 Though first underreported due to the way COVID data was aggregated by county, the Navajo Nation did soon emerge as site of much media coverage. The virus was shedding light on the underlying conditions that had allowed it to spread.

According to the Center for Disease Control’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) —measured through a combination of factors like household income, overcrowding, and access to infrastructure—the rate of “vulnerability” on the Navajo Nation is .9946 out of 1.2 SVI is also being used to track how COVID-19 has disproportionately affected lower income communities and communities of color. But, within the context of public health, what does vulnerability mean and how is it produced? And what if we considered vulnerability not just as a series of interrelated symptoms of inequality in America, but rather a condition actively produced by the policies of racial capitalism and colonialism? What if vulnerability is part of a historically far reaching state project to exclude and marginalize certain populations from the full benefits of American citizenship? What if vulnerability in the case of the Navajo Nation, is part of a long history of settler colonialism and treaty violations?

While there are several causes attributed to the COVID outbreak on the Navajo Nation—including density within households, distance to healthcare, and rate of underlying health conditions—this essay focuses on one: access to fresh water on the reservation. In a pandemic, water is necessary to wash hands and surfaces, and to stay healthy and hydrated. On the Navajo Nation over thirty percent of households don’t have access to piped water, so many people travel to communal wells or water taps, or to the houses of family, for water.3 This reality makes social distancing and isolation challenging or impossible. Lack of running water is not a new problem and is not just the result of poverty on the Nation, as the current media narrative suggests. It is the result of a many decades-long fight to restore rights to water on Diné (Navajo) lands, and to create the infrastructure to make this water accessible.

In the words of Diné geographer Andrew Curley, “When we see statistics stating that 30% to 40% of Diné communities lack running water during a global pandemic, they are not statistics without history. The entire situation is an artifact of colonialism. It is the result of decades of indifference, neglect and deliberate underdevelopment.”4 This is an ongoing struggle that grassroots collectives, citizens, NGOs and agencies like the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) as well as the Tribal Government are currently confronting with particular urgency in response to the pandemic. Neighbors are delivering water barrels, organizations are digging wells, the NTUA is building cisterns and pipelines. Activists are demanding rights to their traditional waters. This essay chronicles a history of settler colonial policies that have attempted to take water from Diné homelands, and the work of tribal members to restore their rights to water.

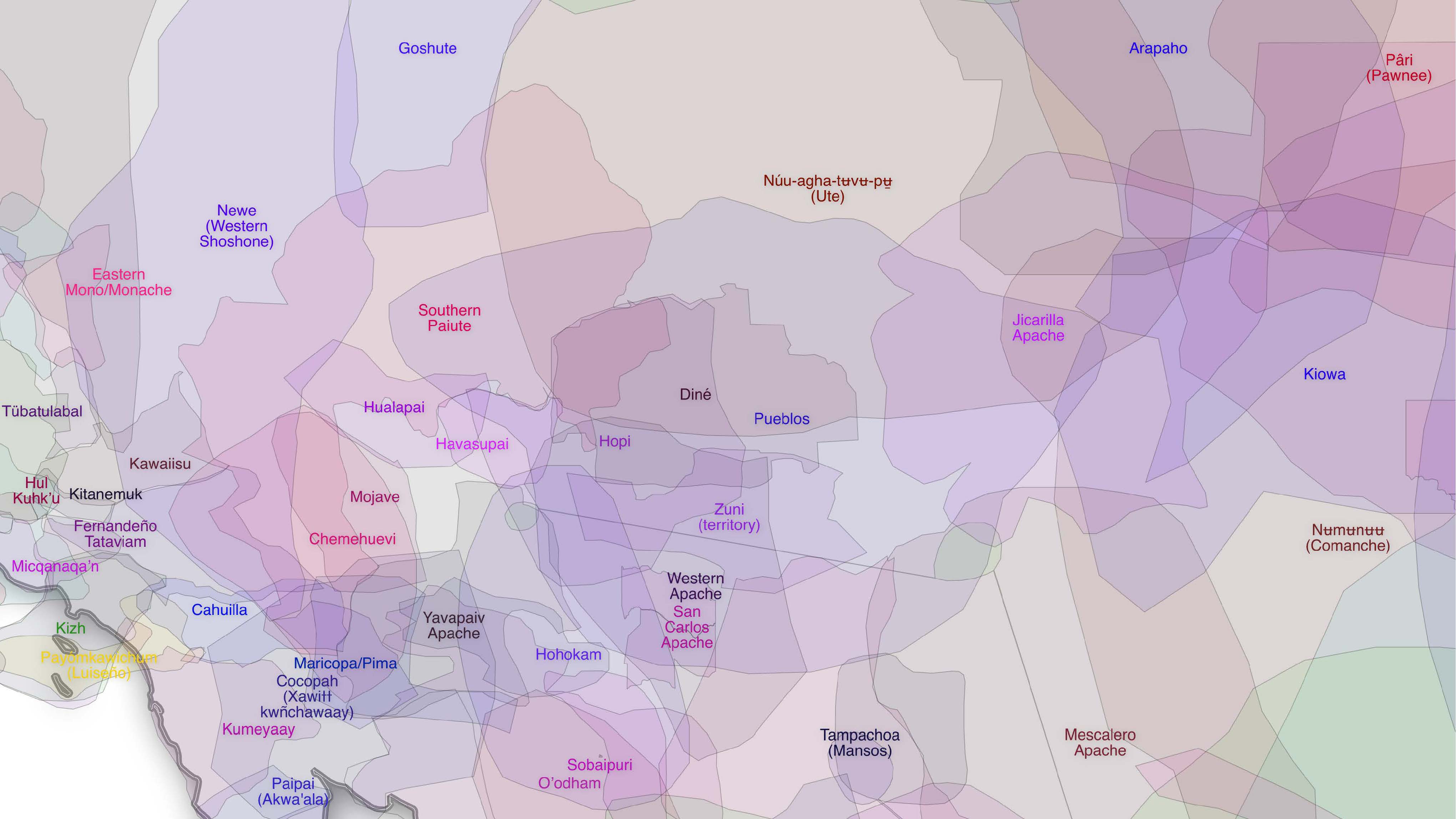

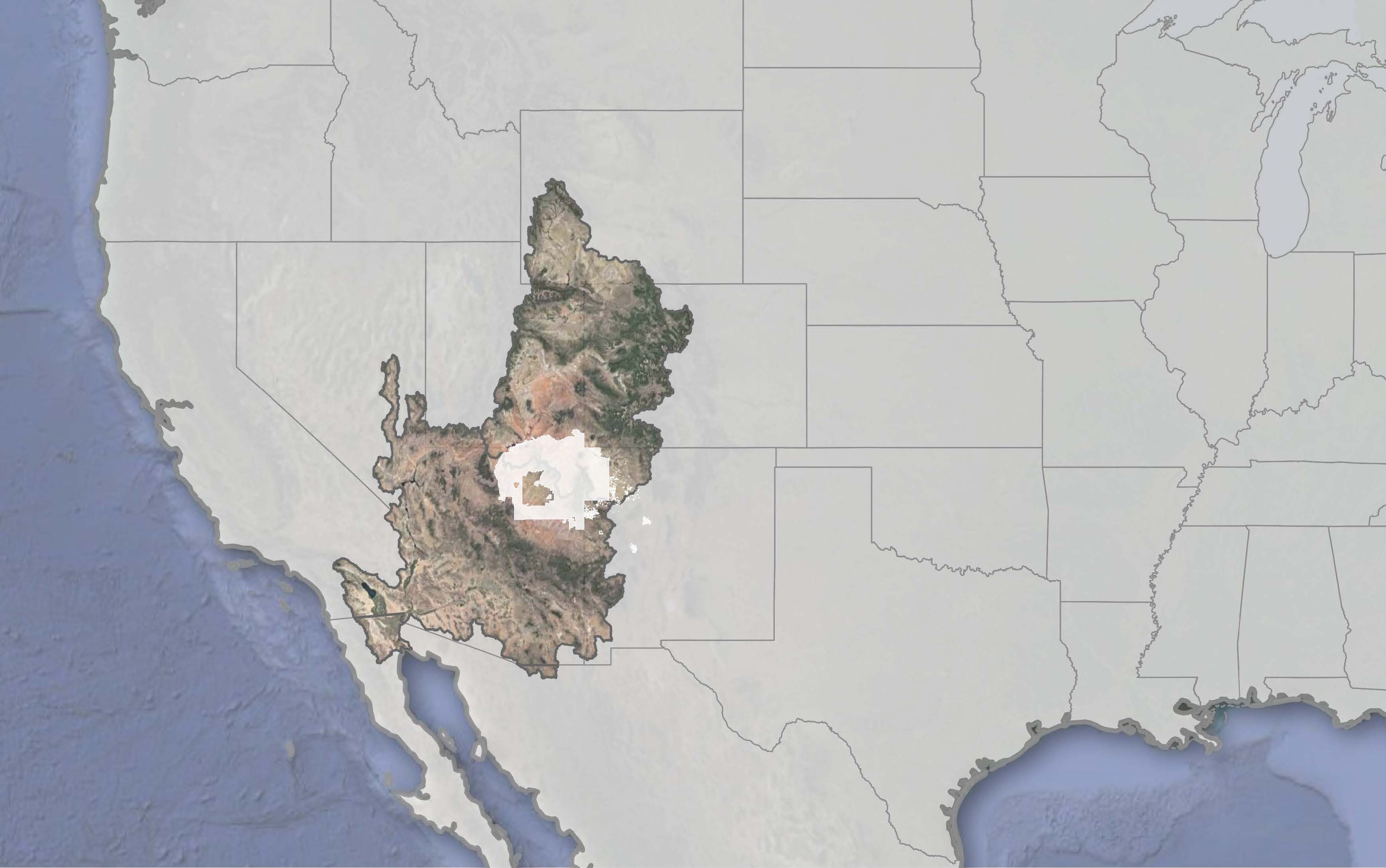

Indigenous territories of the Southwest. Data from Native Land Digital.

II. Diné Bikéyah

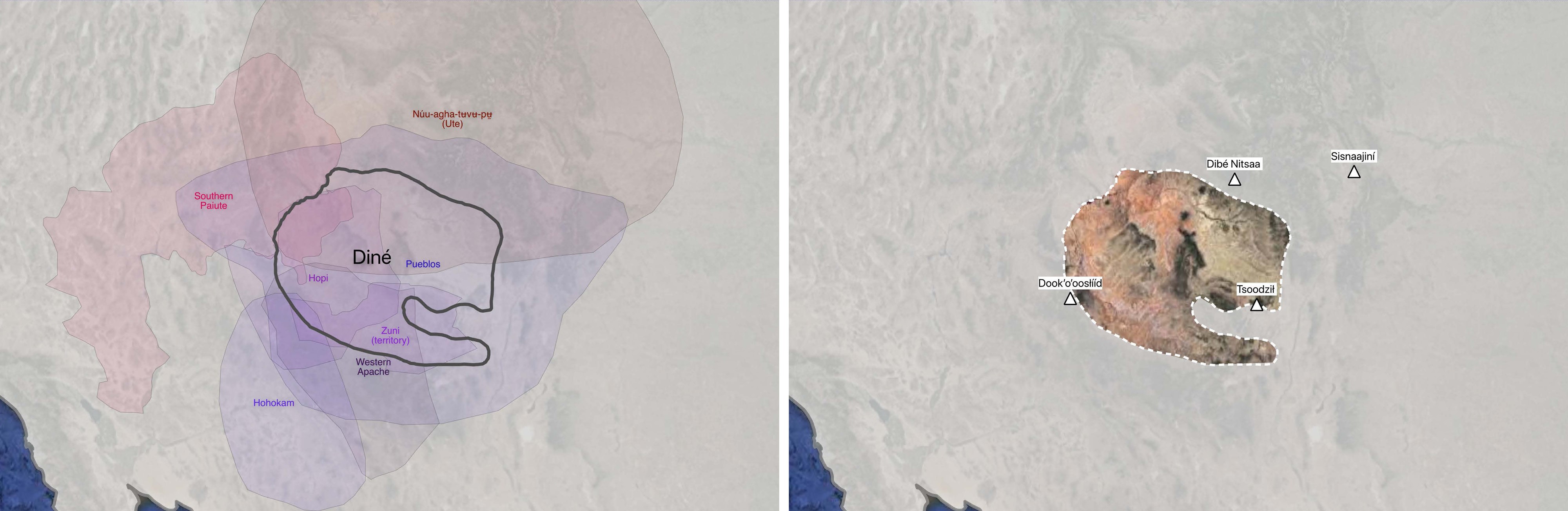

Diné Bikéyah and neighboring nations. (right) Diné Bikéyah.

Diné Bikéyah and neighboring nations. (right) Diné Bikéyah.

The ancestral homelands of the Diné people, Diné Bikéyah, encompass the land between four sacred mountains—Sisnaajiní (Blanca Peak), Tsoodził (Mount Taylor), Dook’o’oosłííd (San Francisco Peaks), and Dibé Nitsaa (Hesperus Mountain) in a territory that overlaps Hopi, Paiute, Ute, and Zuni lands. The boundaries of Diné Bikéyah extend across what are now the states of Arizona, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. The current Navajo Reservation covers much, though not all, of these ancestral homelands.

Jennifer Nez Denetdale describes Navajo land as follows:

Dinétah is the place where earth people and Holy People interacted; their relationships form the foundation of practices and teachings that underlie Navajo life today. The Holy People set the Diné homeland’s boundaries with soil brought from the lower world, placing the soil as mountains in each of the four directions. Diné Bikéyah refers to the lands that lie within the four sacred mountains, which are named Sis Naajiní, or Blanca Peak, in the east; Tsoodził, or Mount Taylor, in the south; Dook’oosłííd, or the San Francisco Peaks, in the west; and Dibé Nitsaa, or Mount Hesperus, in the north. The soil brought from the world below also formed two other mountains: Dził Na’oodiłii, or Huerfano Mountain—east of the center, and Ch’ool’í’í, or Gobernador Knob—the center. These last two mountains are within Dinétah and central to events that occurred when the progenitors of the Diné emerged into the world we inhabit today, which is known as the Glittering World. Traditional Navajo philosophy names these six mountains as the leaders of the Diné. It is in this place that the philosophy sa’ah nagháí bik’eh hózhóón was established through actions and words. Navajo leaders and citizens declare that traditional teachings form the foundation of the sovereignty that the United States recognized in the Treaty of 1868.5

As Denetdale’s telling of Diné Bikeyah’s origin story reflects, the interconnection between surface and subsurface is fundamental to Diné conceptions of land and territory. Further, land is a site of lived tradition and ceremony, a place of relations, and a terrain where plants, animals, and people are supported by mountains, rain, wind, and snow. Land is also not just a two-dimensional plane drawn on a map as colonial mapping practices would render it as. It is also the air, the soil, and subsurface geology, and the water.

III. Treaty

1868 Treaty and map of 1868 Treaty Boundary overlain on Diné Bikeyah.

1868 Treaty and map of 1868 Treaty Boundary overlain on Diné Bikeyah.

The Diné had lived in and moved through Dine Bikeyah for thousands of years, but as the West and Southwest were “opened” to settlement in the mid-nineteenth century that land was claimed by white settlers moving into Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah territories in advance of their anticipated statehood. Settler incursions and land grabs escalated into violent invasion in 1863 when the United States Union Army entered Diné territory, destroying lives and land in a deadly scorched earth policy. Ultimately, the army, led by Kit Carson, forced the Diné people in what was called “the long walk” onto the Bosque Redondo concentration camp in New Mexico territory.

In 1868 the Diné interned at Bosque Redondo signed Naal Tsoos Saní (the Treaty of Fort Sumner), establishing the Navajo Reservation on what amounted to only a quarter of their homelands.6 The treaty created the boundaries of the reservation at the 37th degree latitude to the north, a line passing through Fort Defiance to the south, a longitude parallel through Bear Spring on the east, and to the west a longitude line alongside Cañon de Chelly. Within these boundaries, “The United States agrees that no persons except those herein so authorized to do, and except such officers, soldiers, agents, and employees of the government, or of the Indians, as may be authorized to enter upon Indian reservations in discharge of duties imposed by law, or the orders of the President, shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in, the territory described in this article.”7 While the treaty explicitly stated that those not authorized (i.e. non-Diné) could not settle within the reservation boundary, it said nothing about the use of resources that passed through the reservation (water) or underneath the soil.

This treaty also enshrined several principles of settler colonial governmentality that would go on to become critical in how water rights were conceived of and allocated in the American West. First, it established farming as the primary means for private property acquisition and for federal assistance on the reservation. The treaty provided for allotments for individual Diné farmers, a system of dividing communal land that was replicated in the Dawes Act, and that ultimately left it up to individuals to ask states for access to water on their plot of land instead of the tribe negotiating for water as a sovereign government. The treaty also decreed that, “[the Navajo] will make no opposition to the construction of railroads now being built or hereafter to be built, across the continent.” The railroads would be a primary driver of the rapid settlement of the west and water infrastructure would then make it possible for settlements to take hold.

Naal Tsoos Saní also brought with it the paradoxes of recognition—being recognized as sovereign by the United States government enabled the United States government to dictate what sovereignty meant and the forms through which it could be practiced and acknowledged. Dene political theorist Glen Coulthard describes the politics of recognition like this, “the politics of recognition in its contemporary liberal form promises to reproduce the very configurations of colonialist, racist, patriarchal state power that Indigenous people’s struggles for recognition sought to transcend.”8 In the case of water rights, recognition has meant entering into a process of negotiation, arbitration, and settlement with the state that has then led to compromised rights to water. State and federal laws circumscribe the terms by which one can claim water, the ways in which one might understand water, and the landbase from which it could be claimed.

The treaty established private property ownership, Western agricultural practices, and the logic of expansion on the Navajo Nation and within the documents that governed its existence. And while within the treaty, attention was paid to practices of surveying and the enforcement of property among Navajo “settlers,” there was no mention of subsurface rights, including water. According to the laws governing the establishment of reservations land rights are meant to extend to natural resources unless explicitly stated otherwise.9 However, these obligations were not upheld and over the twentieth century, tribes had to fight for their mineral and water rights.

IV. Reservation

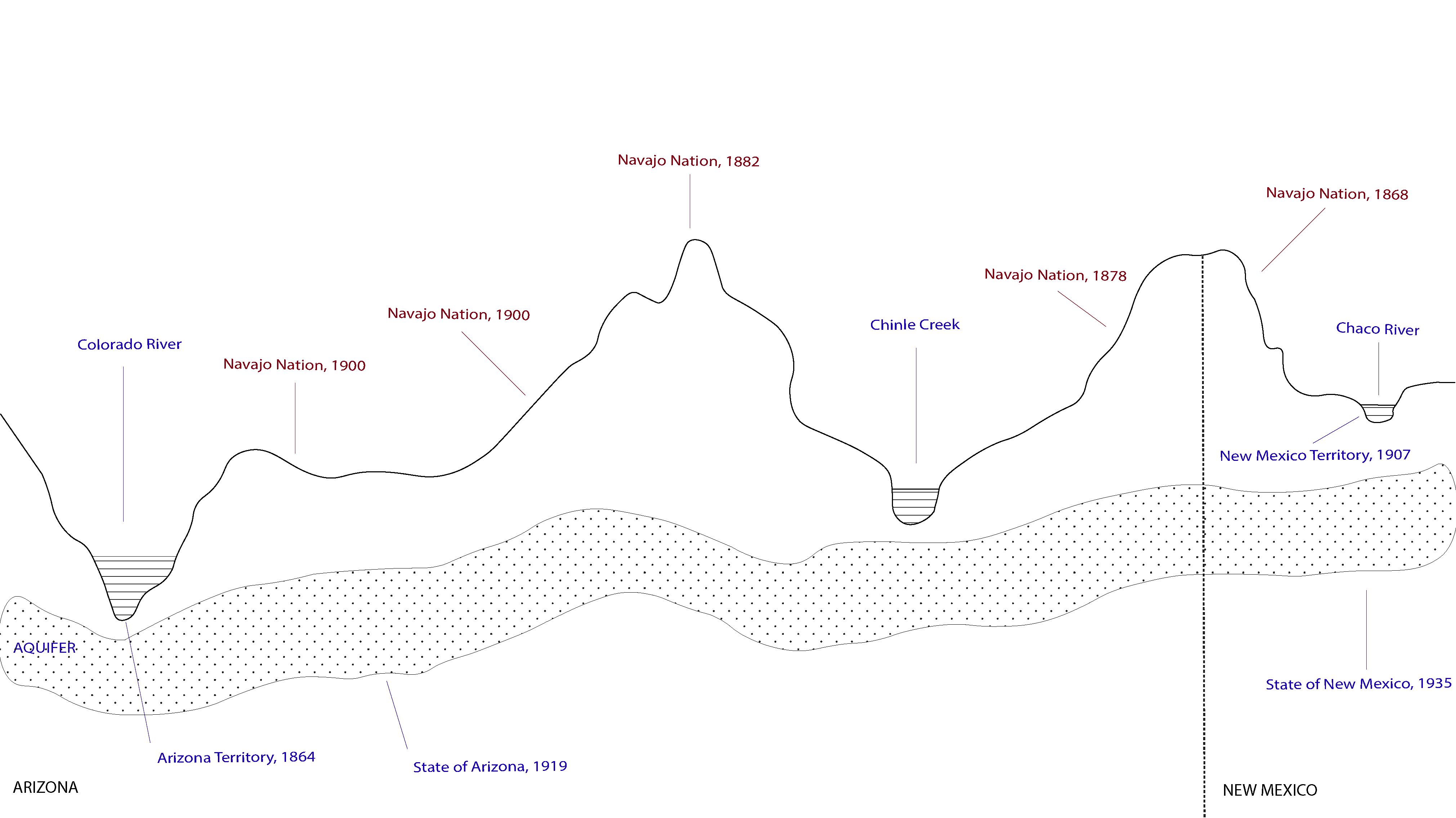

Expansion of the Navajo Reservation 1868-1934.

Expansion of the Navajo Reservation 1868-1934.

Over half a century the land base of the Diné people grew to approximate—but not equal—its original extent as the Navajo Reservation was expanded through executive orders and land purchases. Executive orders were hard won; Diné families struggled to regain land occupied by white settlers and petitioned the federal government relentlessly for reservation boundaries to be redrawn.10 The Naal Tsoos Saní-created reservation contained less than a quarter of Navajo homelands; there was not enough space to sustain ranching and farming, and Diné families wanted to return to their original homes. But the federal government had already started giving this land away in the checkerboard pattern of speculation it used to subsidize railroad development (land sales of alternating parcels would fund the railroad).

As settlers and the Santa Fe Railroad quickly moved in, water became a site of conflict, with settlers trying to expel Diné families from territory near streams and springs. Disputes were often resolved with force. A Diné History of Navajoland quotes Commission of Indian Affairs agent Denis Riordan, “The leader of the Indians Toh-yel-te by name, declared his purpose to die right there sooner than give up the spring. I heard the story of each side fully…I told Toh-yel-te he could begin getting ready to die just as soon as he pleased, that he must leave the place…[T]he Indians accepted my terms.”11 As the government pushed Navajo people off their farms and ranches, settlers were able to claim prior appropriation to secure water rights—a settler concept discussed further below.

Allotment was a tactic for the federal government to divide Native communal land stewardship, individualize and privatize land as property (both on and below the surface), and insert both state and settlers into the fabric of Native territories. Individual allotment holders would then have to deal with the federal government for water rights, and could also be more easily displaced by the federal government, as the following passage from a 1936 letter by families in the now Arizona portion of the Navajo Nation demonstrates:

Over 30 years ago, the government began to survey this land and gave it to Indians in allotments. The Indians were urged to improve this land. The built homes, made corrals, and fenced in their fields, just as the government told them to. Many of the Indians were granted “patterns” [trust patents to the Indian allotments]. Then the first white man rancher settled on the Navajo Reservation at Taylor Springs, he never gave the Indians any trouble, so Indians left him in peace.12

The letter goes on to describe good relationships with white settlers but also settlers who would take Navajo allotments or expand their property lines into them. It also decries the constant relocation of Diné families: “we are paying taxes on this land and still we are asked to move out…” Allotment was a conception and representation of land completely counter to Diné ways of thinking. For the Diné, whose four sacred mountains are made of soil from the underworld, the subsurface, surface, and sky were interconnected. Surveying and allotting practices denied such a view and limited the notion of land and resources.

Ultimately, the government extended the Navajo Nation into this checkerboard area of Arizona but, as Kelley and Francis point out, with the intention of reducing Navajo livestock to prevent erosion and water depletion along the Colorado River as it surged to the newly-built Hoover Dam. By the early 1930s the Colorado River watershed had been neatly split between the five new states of the American West, leaving out native nations.

V. Prior Appropriation

As white settlers began to move into the newly acquired lands of the Southwest—enabled by the Santa Fe railroad that cut across the southern portion of the Navajo Reservation—the then territories created laws to regulate the use of water. Arizona was the first territory to establish a prior appropriation law for water in 1864. Prior appropriation doctrine, “gives unequal rights in streams according to the relative times of beginning use.” This means that whoever first uses the water can lay claim to that, and that claim would be registered with the territorial, and then state, government. Furthermore, water rights are based on not just any use but rather “beneficial use,” defined by the government as “productive.” Productive use is primarily understood as industrial and agricultural, reflecting the needs of the mining industry and settler agriculture in the region.

Use, as legal scholar Brenna Bhandar explains, is a colonial concept directly linked to European practices of cultivation and “improvement.” Such ideology did not recognize Indigenous ways of living with land and territory. Beneficial use provided a legal framework for settlers to impose specific logics of extraction and development on to Diné lands, and then turn that framework into a mechanism to expropriate water in those lands.

Prior appropriation law also established junior and senior water rights, whereby the first property owner to claim rights has “senior” rights, and subsequent claimants have “junior” rights; junior rights holders can lay claim to less water and their water access is reduced during drought times. Native nations were usually given junior water rights, and in later water rights settlements, would be pressured to accept junior water rights in exchange for funding for water infrastructure.

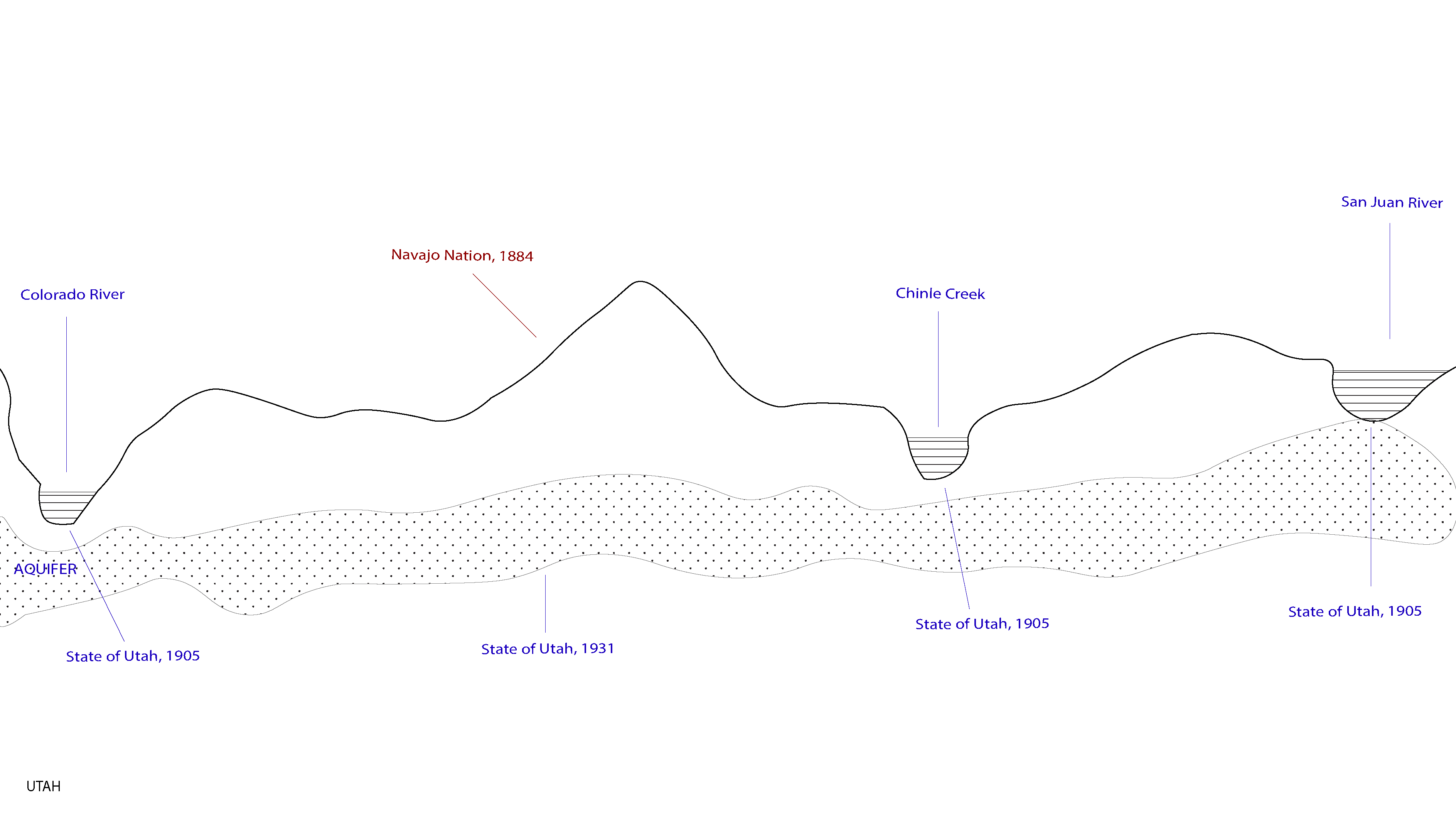

In 1903, Utah passed prior appropriation laws for surface water, and in 1935 it added groundwater to prior appropriation doctrine. New Mexico passed prior appropriation laws for surface water in 1907 and ground water in 1931. Arizona’s prior appropriation policies were signed into state law in 1919.

According to prior appropriation in the public domain “state law (usually the law of appropriation to actual use) governs waters upon a Federal reservation as in any other part of the State.”13 This includes reservation land. However, the federal government recognized that state laws had not been acknowledging and protecting the rights of tribal governments and citizens. In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Winters v. United States that when Congress set aside lands for a reservation, it impliedly reserved sufficient water for Indian tribes to fulfill the purpose of creating the reservation. However, Winters did not set forth a method to quantify water rights beyond “sufficient water to fulfill the reservation’s purpose.” The U.S. Supreme Court would later establish a method for quantifying agricultural water rights in Arizona v. California (1963), which adopted the practicably irrigable acreage standard.

Land and water jurisdiction on the Navajo Nation in Utah.

Land and water jurisdiction on the Navajo Nation in Utah.

Land and water jurisdiction on the Navajo Nation in Arizona and New Mexico.

Land and water jurisdiction on the Navajo Nation in Arizona and New Mexico.

VI. Colorado River Compact

Colorado River Compact 1922.

Colorado River Compact 1922.

By the early 1920s, as cities like Los Angeles, Tucson, and Phoenix grew, it became clear that water would be a finite, and much vied for, resource in the west. Wending through seven states, the Colorado River and its tributaries supply most of the fresh water in the region. In 1922, these states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming) forged the Colorado River Compact, to “equitably divide” the waters of the Colorado and establish “the relative importance” of various beneficial uses of the water. Under this legislative agreement the seven states had rights to 7,500,000 acre feet a year from both the upper and lower Colorado River watersheds. Anticipating population growth, the lower Colorado River basin could increase this by one million acre feet a year.14

While article seven of the Compact states that, “nothing in this compact shall be construed as effecting the commitments of the United States of America to Indian Tribes,” there were no tribal representatives at the negotiating table, and the compact does not explicitly indicate how much water would go to the many Native nations within the watershed at the time of signing.15 In fact at the time the compact was signed there was no mechanism to enforce existing commitments with Tribes. While the Winters Doctrine had established that Native nations could claim enough water rights as to sustain the population of their reservation, there was no established standard to quantify those water rights nor avenues to bring these claims to court. Further, tribal governments fell into an intentional jurisdictional gap: sovereign tribal governments had treaties with the federal government and, as so-called domestic dependents, negotiated with the federal government. However, water rights were allocated to and divvyed up by states.

In 1922, when the Compact went into effect, the Navajo Nation was smaller than it is today, meaning that the existing commitments would only apply to those 1922 boundaries but as reservation boundaries extended individual Navajo citizens would have to continue to petition the state for water rights. But most importantly, the Colorado River Compact treated water as property to be commodified, owned, and governed—just as land had been by the Dawes Act. For the Diné, through whose lands the river runs, its water holds other meanings. Water is a relative not a resource to be claimed and exhaustively extracted for commercial development. Water is to be lived with, sustained, and cared for. The compact framed water through an entirely different jurisdictional apparatus, and through a world view of development and extraction. It was this logic that would make water more scarce and less cared for in Diné Bikeyah.

VII. Settlements

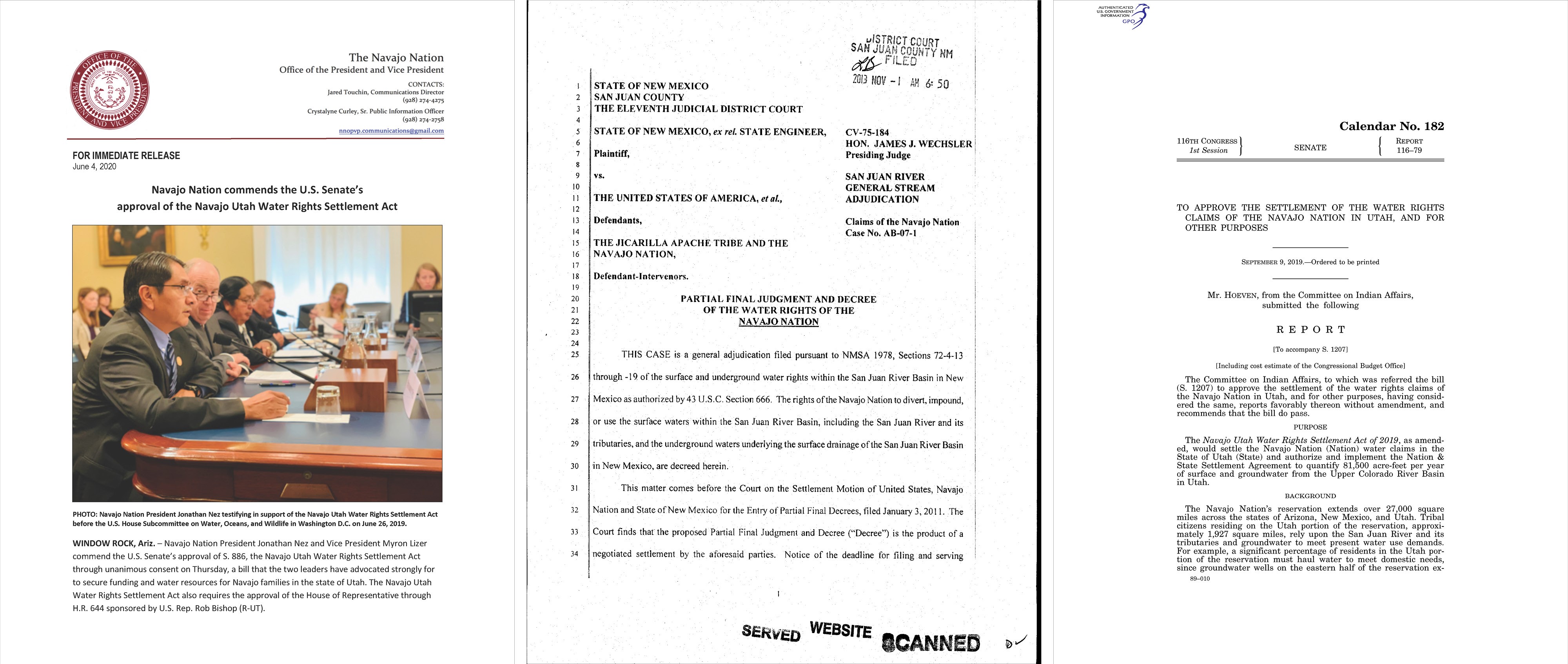

Water rights adjudication and settlements between the Navajo Nation, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico.

Water rights adjudication and settlements between the Navajo Nation, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico.

The decades following the Colorado River Compact saw the Navajo land base increase, but its water rights stagnate. Winters promises went unfulfilled while water both on and below the surface of Diné Bikeyah was siphoned and drained for state and federal projects.16 These projects would have lasting consequences. During WWII, the United States developed its nuclear program by extracting uranium and testing bombs in the Southwest, primarily on Indigenous land in Arizona, Utah, New Mexico and Nevada. Ample stores of uranium were found on the Navajo Nation, and private mining companies contracted by the federal government quickly began leasing Navajo land. Brokered by state governments, these leases directed revenue earned on Navajo trust land (as opposed to allotment land) to be held in trust by the federal government to disburse to a tribal government (whose structures it had created). As a result, land leases were negotiated in favor of mining corporations, while uranium and coal contaminated the bodies of miners and the ecology of the region as they leached into the water table and dissipated into the air.

Elsie Mae Cly describes the effects of uranium mining on the landscape “when the rain comes, you can see the white stuff that comes down the walls of the mesa from the mine.” Uranium flows downhill, into streams and through the water table. It enters bodies Cly continues, “There is a ceremony that the Navajo do whenever they get some kind of illness. [Ceremonies are performed now] all the time… A lot of Navajos live near the mines.”17

The Colorado River Compact took water from Indigenous nations and put it under the jurisdiction of state governments. Mining exploited commodified land, polluted groundwater and drained aquifers. These two process went hand in hand: the coal powered Navajo Generating Station used Colorado river water to generate electricity for cities in Arizona, Nevada, and Southern California. This electricity was also used to pump water into aqueducts of the Central Arizona Project, which diverts Colorado River water across the desert to the Phoenix and Tucson areas.

During the 1960s and 70s, two legal decisions changed how Indigenous nations approached water rights claims. The first was the 1963 supreme court ruling Arizona v California, which stated that when the federal government created reservations in the region, “it reserved not only the land, but also the use of enough water from the Colorado River to irrigate the irrigable portions of the reserved lands.”18 The capacity of irrigable portions of reservations could now be used in water rights cases as the metric by which Winters rights were measured. A 1971 US Supreme Court ruling waved US sovereign immunity for water rights claims and established state courts as the venue for water adjudication with tribal governments. Though this created a process by which tribal nations could claim their water, it did so by enacting what Jeff Corntassel calls “forced federalism.”

Through forced federalism the government to government relationship between Indigenous nations and the United States was reduced instead to negotiations between tribal and state governments. This meant state governments were deciding how much water to allocate to Indigenous nations when they in fact wanted that water themselves. Consequently, water rights adjudication often took the form of a legal settlement. In water rights settlements, tribal government claims to water in both total acre feet and seniority were exchanged for an expeditious resolution and for funding to build the infrastructure needed to bring water from rivers into communities and homes. The settler state asked tribal governments to settle for less water. Anthropologist Audra Simpson writes that Indigenous politics often challenge that which is perceived as settled. “By settled,” says Simpson, “I mean ‘finished,’ ‘done,’ ‘complete.’ This is the assumption that the colonial project has been realized: the lands have been dispossessed; its owners have been eliminated or absorbed. This clean slate settlement is now considered a ‘nation of immigrants’ (except the Indians). But this belief demonstrates a blindness to the structures of settler colonial nation-statehood—of its labor, its pains, its agonies…”19 Water rights settlements reproduce the sense of settling that Simpson describes. In overlooking the legal, political reasons for water scarcity on the Navajo Nation the current narratives of vulnerability to COVID-19 could risk obscuring what’s really at stake.

As scholars like Melanie Yazzie have pointed to, water rights settlements often aimed to undermine Indigenous claims to water as understood both through the Winters framework and outside of it. Yazzie writes of the paradox of Indian water rights laws that on the one hand establishes such rights as uncircumscribed and prior while at the same time legal adjudication introduces conservative interpretation of these laws that limit water allocation to a quantified minimum of use.20 For these reasons Navajo activists and citizens pushed back against water settlement offers in the first decades of the new millennium. In so doing they were arguing for an approach to water rights that did not limit those rights to settler colonial frameworks dictated by the federal government, but rather a notion of rights that upheld their unbroken relationship to the waters of their ancestral homelands.

Andrew Curley describes how activists protested the very limited water rights agreements suggested by state governments (for example the 2012 Little Colorado River Compact which if approved would have curtailed Navajo water rights) as well as the lack of transparency in tribal to state government negotiations. Curley explains that the framework of settlements themselves aim to limit the political horizon of water struggles: “Water settlements are also ontological constructions that convert rivers into notions of ‘acre-feet,’ divorcing water from the land, species, and kinship networks. Indigenous peoples across the world oppose these kinds of colonial limitations while working to maintain prior resource ‘jurisdictions.’”21

According to Curley the activists and tribal offices participating in water rights settlements, and surrounding debates, are navigating a paradoxical terrain. They must fight to meet the very real need for water infrastructure on the Navajo Nation while still opposing the settler colonial logics of water rights settlements. “Diné water governance transcends the colonial limitations of western water law through use of both pragmatic and decolonial practices. Diné advocates work to maximize water quantification while supporting the idea of traditional water uses for sustainable lifeways,” he writes.22

A report commissioned by Arizona congressperson Raul Grijavla recognizes that the federal government has, historically, blatantly ignored its obligations to native nations in the interest of settler expansion in the West, “Tribes often hold the most senior water rights in many river basins. Under federal law, the federal government must protect these tribal water rights. However, for more than a century, the federal government has failed to fulfill this role and, in many cases, actively undermined tribal water rights to provide water to non-Indian neighbors. To encourage people to move West in the 1900s, the federal government provided land and infrastructure, building the pipes and systems needed to bring heavily subsidized irrigation and drinking water to settlers. This water frequently came at tribes’ expense. As a result, today, many tribes still lack access to water.”

VIII. Wet Water

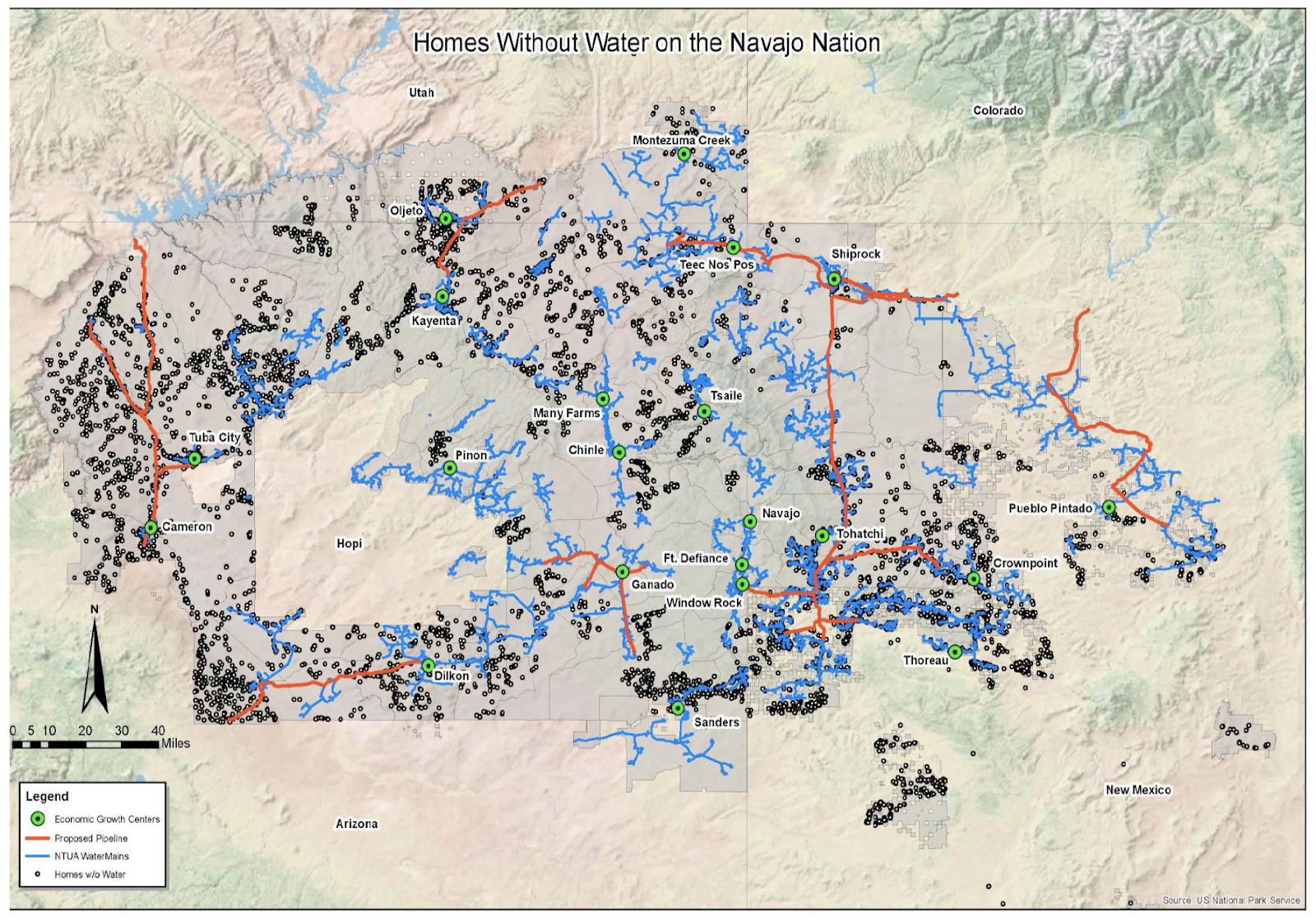

Houses without water and proposed water infrastructure on the Navajo Nation. From Navajo Tribal Utility Authority.

Houses without water and proposed water infrastructure on the Navajo Nation. From Navajo Tribal Utility Authority.

There are currently two water rights settlements that have been negotiated between the Navajo Nation and the states it borders, one as recently as last year. The 2019 Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement Act allocates 81,500 acre-feet per year of surface and groundwater from the Upper Colorado River Basin in Utah to the Navajo Nation. It also authorizes over 200 million dollars for the creation and maintenance of water development projects to be held in trust for use by the Navajo Nation.

The 2010 San Juan River Basin Navajo Water Rights Settlement agreement diverts 37,764 acre-feet a year from the San Juan River in New Mexico and directs it to the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project—a pipeline-building project that is anticipated to bring running water to 250,000 residents of the Navajo and Jicarilla Apache Nations, and city of Gallup, New Mexico by 2040.23

A water rights settlement between Arizona and the Navajo Nation is still under adjudication after the tribal council ended negotiations for the Little Colorado River Settlement. Earlier this year, republican law makers in the Arizona state legislature proposed a bill that would require Native nations to settle water rights claims before they could renegotiate gaming compacts.24 As population increase and climate change put pressure on Arizona’s limited water supply, state lawmakers are increasingly pushing tribes to settle their water rights in agreements that will be binding in perpetuity.

Meanwhile people are working on the ground in the Navajo Nation to turn “paper water” provided through Winters doctrine and recent settlements into “wet water” that can come out of a tap in people’s homes. This includes officers in tribal government, the Navajo Utility Authority, and grassroots groups. Tó Bei Nihi Dziil (Water is our Power) is a collective of Diné organizers who fight for water security through teach-ins about the history of struggle for water rights in Diné Bikeyah and collective conversations on grassroots strategies to gain access to water in communities. Citing the role of tó within Diné traditional political thought and within international human rights frameworks, Tó Bei Nihi Dziil say,

Together we can develop and enforce a Water Rights negotiation process that respects our “Free, Prior and Informed Consent” and helps us claim, capture, use, conserve, and protect our precious water resources so that they are abundant, clean, and available for all the current and future needs of our people and homelands. We must continue to create and strengthen our Diné lifeways, instead of weakening our traditions—our strength—due to the misplaced power we give to the Navajo Nation government…let’s unite to develop the movement for our water, our land, and democratic control over our local resources.25

Utah Diné Bikeyah, an NGO that formed to protect Indigenous sacred lands in Utah. The group is particularly active in San Juan County which includes the Utah portion of the Navajo Nation. There they have been advocating for legislation that would bring running water and electricity to Westwater, a Diné neighborhood of Blanding, Utah. Utah Diné Bikeyah’s work offers a holistic model of advocacy that sees the fight for land, traditional agricultural practices, and water access as politically intertwined.26 Since the pandemic broke out already existing networks to bring water to elders in remote areas of the Navajo Nation have increased. Zoel Zohnnie, for example, founded Collective Medicine in the weeks following the onset of COVID-19 to deliver water barrels to elders and mobility impaired people on the reservation. Darlene Arviso has been bringing water barrels in the Eastern area of the reservation for years.27 Mutual Aid collectives like Ké Infoshop and Navajo Hopi Covid-19 Relief, among other groups, deliver food and water across the Navajo Nation.

Within the tribal government, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority is working to build the pipelines planned for in the Navajo Gallup Supply Project; work that extends back beyond the passage of the project to laying out and planning where pipeline will go. Under the CARES act, the Navajo Nation has received $714 million. The majority of that ($476.6 million) will go to improving infrastructure like electricity, broadband internet, and water: $20.9 million for cisterns systems, $18.6 million for wastewater systems.28

The use of CARES act funds for water and electricity poses the question: what does care look like and what does it take to get it? Though Navajo Water Rights struggles are over 150 years old, the pandemic is exposing these struggles to many Americans for the first time. Care is political, and in the case of the Covid relief on the Navajo Nation, care requires reckoning with centuries of settler colonial history that are producing conditions of vulnerability today. A vulnerability index may helpfully point to areas where relief is needed in the present. But more work needs to be done to understand how that vulnerability has been produced and what ends it is serving. And work must be done to dismantle it. This is the work that collectives, citizens, and agencies on the Navajo Nation have been doing for decades. Raul Grijavla’s congressional report concludes “the United States expects all nations to live up to their treaty obligations; it should live up to its own.”29 Care requires caring for treaty obligations and understanding so-called resources like land and water through the terms of the Indigenous nations those treaties are with. Scholar Maria Puig de Bellacasa calls for, “exploring an idea of care that goes beyond moral disposition or well-intentioned attitude to consider its significance for knowledge construction.”30 Here the kind of care that will forestall future devastation from the pandemic or other health emergencies requires foregrounding water as a right not as a commodity or form of property separated from the land it runs through and under but instead as enmeshed in and a part of it. It will require caring for water as an element of Diné sovereignty over Diné Bikeyah.

Flyer from ToÌ Bei Nihi Dziil.

Notes

- Hollie Silverman, Konstantin Toropin, Sara Sidner and Leslie Perrot, “Navajo Nation surpasses New York state for the highest Covid-19 infection rate in the US,” CNN, May 18, 2020, Link

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) Fact Sheet, accessed August 26, 2020, Link

- Navajo Water Project, Link

- Andrew Curley, “Contested Water Rights Settlements Inflamed the Navajo Nation’s Health Crisis,” High Country News, August 11, 2020, Link

- Jennifer Nez Denetdale, “Naal Tsoos Saní (The Old Paper): The Navajo Treaty of 1868, Nation Building and Self-Determination,” American Indian Magazine, vol. 2, no. 19 (Summer 2018), Link

- Denetdale, “Naal Tsoos Saní.”

- United States of America and the Navajo Tribe, “1868 ye̜e̜da̜a̜ naabeeho dinee̕ bilagaana yił a̕hadaa̕dees ta̕ne̜e̜,” (“Treaty between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians,”), August 12, 1868.

- Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 3.

- Democratic Staff of the Natural Resources Committee, Water Delayed is Water Denied: How Congress Blocked Access to Water for Native Families, October 10, 2016, Link

- For a detailed, oral-history based account of the creation and expansion of the Navajo Nation in the context of railroad development and settler colonial expansion see Klara Kelley and Harris Francis, A Diné History of Navajoland (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2019).

- Kelley and Francis, A Diné History of Navajoland, 146.

- Kelley and Francis, A Diné History of Navajoland, 162.

- Samuel Charles Weil, Water Rights in the Western States, (San Francisco: Bancroft Whitney Company, 1911), 238.

- Colorado River Water Compact, August 19, 1921, 1, Link

- Colorado River Water Compact, 3

- For an excellent, and concise, telling of this history see Andrew Curley, “Contested water settlements inflamed the Navajo Nation’s health crisis,” High Country News, August 11, 2020.

- In Doug Brugge, Tim Benally, and Esther Yazzie-Lewis, “Uranium Mining on Navajo Indian Land,” Cultural Survival Quarterly

- Arizona v. California, 373 U.S. 546 (1963)

- Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 11.

- Melanie K. Yazzie, “Unlimited Limitations: The Navajos’ Winters Rights Deemed Worthless in the 2012 Navajo–Hopi Little Colorado River Settlement,” Wicazo Sa Review vol. 28, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 26.

- 116th Congress of the United States, S.1207, “Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement Act of 2019,” September 9, 2020.

- Andrew Curley, “’Our Winters’ Rights’: Challenging Colonial Water Laws,” Global Environmental Politics vol. 19, no. 3 (August 2019): 57-76.

- “Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project Planning Report and Final Environmental Impact Statement,” United States Bureau of Reclamation website, updated August 12, 2019, Link

- Ryan Randazzo and Andrew Oxford, “Arizona lawmakers want to use casino agreements to force tribes to settle water disputes,” Arizona Republic, January 18, 2020, Link

- Colleen Cooley and Janene Yazzie, “Tó Bei Nihi Dziil ‘Water is our Power’ Teach-in,” Censored News, August 10, 2015, Link

- Alastair Lee Bitsóí, “Westwater Needs Water,” February 8, 2020, Link

- Laurel Morales, “For Many Navajo, A Visit From The ‘Water Lady’ Is A Refreshing Sight,” NPR, January 6, 2015, Link

- Alyssa Becenti, “$174 Million Still up for Grabs,” Navajo Times, September 10, 2020, Link

- Raul Grijavla, “Water Delayed is Water Denied: How Congress Blocked Access to Water for Native Families,” A report by the Democratic staff of the House Committee on Natural Resources, October 10, 2016, Link.

- Maria Puig de Bellacasa, “Matters of care in technoscience: Assembling neglected things,” Social Studies of Science vol. 41, no. 1, (February 2011): 86.