Legal Aid Society: Red Hook

00. INTRODUCTION

When our team was first presented with the case brief for our Legal Aid Society client, we were introduced to a teen like many others. We were introduced to their day-to-day life, and their love of sports, someone who would do anything to stay on their team, even commuting long distances to do so. Despite their efforts, they lived within systems that wanted to enclose them and relegate them to the margins. They were exposed to daily systemic injustices, but through careful examination, we saw how systemic failures within the Department of Education, particularly regarding their IEP (Individualized Education Program), would play a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of their athletic and academic career. An IEP is a legally binding document guaranteeing educational accommodations for students with disabilities, defined by the NYC DOE as “a written statement of our plan to provide your child with a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in their Least Restrictive Environment (LRE).” The neglect of this student’s IEP surprised us as it functioned as an instrument of spatial injustice. Through geospatial analysis of this student’s trajectory, we demonstrate how IEP non-compliance in New York City schools precipitates the removal of extracurricular supports, like football for our client, eliminating critical protective structures and channeling Black disabled students of color into policed geographies. This work is founded on critical race disability studies, Black urbanism, and carceral geographies.

01. LEGAL AID SOCIETY PARTNERSHIP

The Legal Aid Society provides free legal representation to low-income New Yorkers on issues including criminal trials, parole revocation and appeals, juvenile justice, and child protection cases, and civil issues such as housing and immigration. The Video Mitigation Unit is an in-house unit of The Legal Aid Society and is among the first state public defender organizations to explore their clients’ lives through video to convey their character, aspirations, traumas, difficulties, and often, transformation. In certain cases, video can be more effective than traditional written requests, with extraordinary potential for low-income clients. Legal Aid has submitted 22 mitigation videos since September 2019. Of the cases decided, the unit’s work yielded reduced sentences, alternatives to incarceration, and elimination of bail conditions.

Our team worked with The Legal Aid Society to apply spatial analysis methods to their mitigation cases. While Legal Aid’s attorneys documented clients’ personal stories through interviews, we mapped the physical realities of their circumstances, revealing how policy failures create measurable spatial consequences. Using GIS tools and public data, grounded in critical race and disability theory, we developed time-space maps tracking their clients’ daily routines before and after losing football eligibility, which may have been avoided through the proper execution of the students’ school supportive services. Our visualizations also exposed resource gaps by correlating the proximity of the client’s home with the locations of neighborhood program availability. Through weekly meetings with Legal Aid attorneys, their video mitigation staff, and student advocates, we connected spatial patterns to legal arguments. These collaborations transformed our maps into evidence of systemic failure, showing how institutional abandonment in education and public resources follows geographic pathways that predate courtroom appearances.

02. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The marginalization of disabled students of color is not accidental but systemic—a convergence of spatial injustice, bureaucratic exclusion, and state abandonment. These three frameworks help untangle this case:

Spatial injustice as resource exclusion: The uneven distribution of educational resources—from IEP supports to sports teams—follows racialized geographic lines. Schools in affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods hoard opportunities, while schools serving Black and Latinx students face chronic disinvestment (Lipsitz, 2007). The Public Schools Athletic League (PSAL) mirrors this pattern: its teams cluster in well-resourced districts, leaving students in areas like the Bronx and Central Brooklyn with fewer options (Jimenez v. NYC DOE, 2022).

Bureaucratic violence in policy design: Eligibility rules like the PSAL’s “5+1” academic requirement (Public Schools Athletic League, 2025) appear neutral but weaponize disability neglect. By failing to account for IEP accommodations (e.g., modified grading, extended time), these policies punish students for systemic failures. Annamma’s (2018) work shows how such bureaucracy reframes exclusion as “fairness,” masking the violence of arbitrary standards.

Organized abandonment’s carceral logic: When schools withhold IEP services or PSAL access, they don’t merely “fail” students—they actively funnel them toward punitive systems. Gilmore’s (2007) theory clarifies this: underfunded schools, exclusionary policies, and over-policed neighborhoods are interconnected strategies of racial capitalism (Riley et al., 2024). The result? Disabled students of color lose not just sports eligibility, but also pathways to safety and stability. Together, these lenses reveal how IEP gaps and PSAL disqualifications aren’t isolated issues, but deliberate outcomes of a system designed to marginalize.

03. CONCERNS

The IEP as an Unimplemented Safeguard: An IEP is a federal civil right under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), mandating schools provide tailored supports to students with disabilities. Our client’s IEP was established in middle school for mental health-related needs. No two IEPs are meant to be the same; each document is tailored to an individual student’s needs. For example, a student with ADHD might require additional test time, permission to work in quiet environments for specific tasks, or modified assignments to help combat overstimulation, creating conditions where the student can complete work comfortably and have equal opportunities for success.

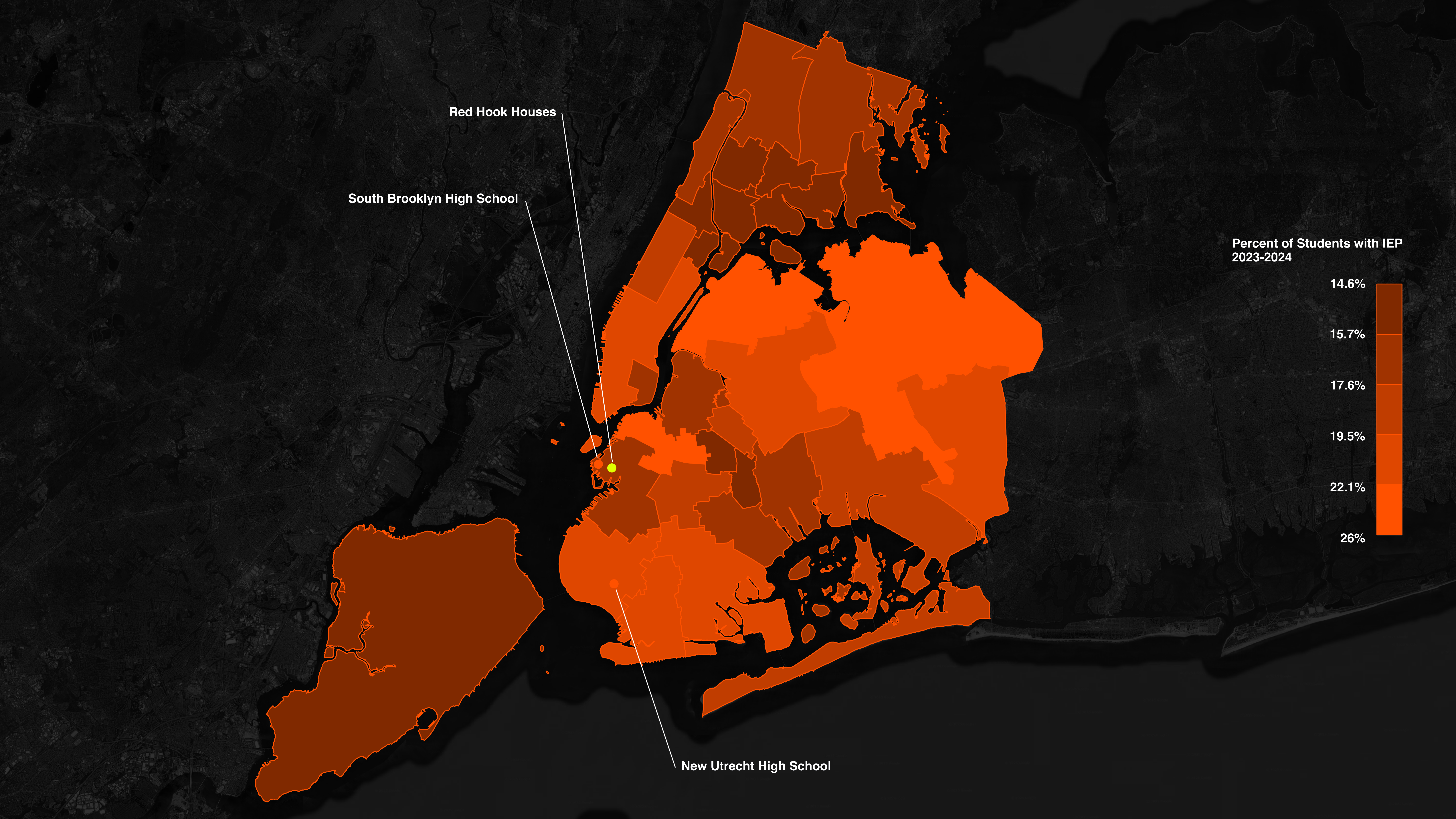

Systemic inequities in the school district create bureaucratic hurdles that prevent instructors from effectively implementing IEP supports. Many students, including our client, face additional challenges with how their IEP was managed. While research suggests proper IEP implementation could have helped maintain our client’s sports participation, the reality is more complex. According to the NYC Department of Education’s Annual Special Education Data Report (2019), improved IEP compliance (84.3% of students receiving recommended services in 2018-2019) correlates strongly with rising graduation rates and declining dropout rates. This suggests that when properly executed, IEPs can significantly impact student outcomes, making their inconsistent implementation particularly consequential. The following map (Figure 1) depicts the percentage of students in the 2023-2024 school year with an IEP distributed across the New York City school districts. Our client’s school districts show high rates of students with IEPs compared to other school districts throughout the city.

Figure 1. Percentage of Students with an IEP in 2023-2024 (per New York City School District)

Figure 1. Percentage of Students with an IEP in 2023-2024 (per New York City School District)

The following video compilation (Figure 2) depicts the stigmatization of IEPs. Our client’s response to his IEP is representative of this stigmatization and its effect on students with an IEP.

“I don’t like people really knowing I had an IEP, because they looked at it like, ‘oh, you’re dumb’”

Mapping the Absence: When Football Became Compensatory Infrastructure: The disappearance of our client’s football participation exposed a dangerous paradox: while their IEP theoretically provided structure, it was the approximately hour-and-a-half commute to a school that showcased the client’s commitment to what they loved most, football. The following daily commute comparison maps (Figure 3) depict the stark difference between when our client was commuting to school to play football versus when they were not.

Spatial-temporal analysis reveals how this daily routine created external discipline that their school supports may have failed to match without a properly executed IEP. The following daily schedule comparison maps (Figure 4) quantify what was lost: 5.5 hours per day of structured time.

Mapping the Absence: Community Resources: The following opportunity maps (Figure 5) tell the rest of the story. In this recreational desert where YMCAs and Boys & Girls Clubs are conspicuously absent, football was not just a sport; it was critical infrastructure for youth in neglected areas attending overcrowded and underfunded schools. Using the toggle to swipe between the two maps reveals how what the city reports as “resources” for the Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill-Gowanus-Red Hook neighborhood is much different from what is relevant and appropriate for those in a similar demographic of the client (NYC Department of Planning). While the left-hand side shows all categorized services reported by the city and facilities added by the researchers, the right-hand side trims this list of those locations that are not applicable to the client’s given interests; examples to illustrate this filtration include the removal of senior centers, infant-feeding sites, ESOL classrooms & Spanish language centers, electrical-transformer stations, etc. Research confirms such programs compensate for systemic failures: the routines prevent delinquency, mentors replace missing guidance, and social bonds counteract isolation (Spruit et al., 2018; Goodman et al., 2021).

When the field lights went off on their athletic career, our client did not just lose a game, they lost the scaffolding holding their world together.

04. METHODOLOGY

For our spatial analysis, we combined three evidence-based approaches. We start with an IEP distribution mapping, which visualizes neighborhood disparities in special education support and contextualized NYC DOE report linking IEP access to more favorable outcomes and vice versa. Second, a time-geography tracks our client’s daily commute from Red Hook Houses to two different high schools, using MTA transit logs to quantify how the school’s location and consequent commute and the client’s football schedule provided structure. Third, a time analysis tracks our client’s daily schedule to visualize the hour-by-hour difference in our client’s life when they were playing football and when they were not. Fourth, opportunity mapping documents infrastructure gaps through NYC Planning Department data, revealing the lack of health/human service facilities, among other central services, absent from the client’s neighborhood; herein, we mark a sharp distinction to the official narrative that the city supports all residents of this area through relevant and applicable services. Taken together, these methods make visible how spatial inequities in education and recreation intersect at our client’s address.

05. IMPLICATIONS

Our research generates several actionable insights across three professional domains. Our geonarratives convert transit logs and opportunity maps into forensic evidence for legal practitioners, documenting how spatial inequities manifest as institutional neglect in individual cases. For policy makers, we expose how IEP implementation gaps and PSAL eligibility rules collaborate to create what we can understand as de facto educational sacrifice zones, these are geographic areas where systemic abandonment becomes spatially predetermined. For urbanists, these findings demand trauma-informed design: the co-location of youth mental health services with high-need schools and athletic facilities within 15-minute neighborhoods of disinvested areas like Red Hook. By rendering these patterns visible, we redefine accommodations through a spatial justice lens, where every IEP provision and recreation center placement becomes both a legal obligation and an urban survival mechanism.

05. REFERENCES

Dancig-Rosenberg, Hadar and Dancig-Rosenberg, Hadar and Dixon, Peter, “JUSTICE OF OUR OWN” DEFINING SUCCESS AT THE RED HOOK COMMUNITY JUSTICE CENTER (April 01, 2025). Vanderbilt Law Review, volume 78, Bar Ilan University Faculty of Law Research Paper Forthcoming, Columbia Public Law Research Paper Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5202803 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5202803

Fünfgeld, Hartmut, Darryn McEvoy, and Karyn Bosomworth (2013). Resilience and Climate Change Adaptation: The Importance of Framing, Planning Practice & Research, 28:3, 280-293

Graham, Stephen, and Simon Marvin. Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. Psychology Press, 2001.

Kavanagh, Michael, “Public Housing in the New York City: The Case of the Red Hook Houses” (2013). African & African American Studies Senior Theses. 19. https://research.library.fordham.edu/aaas_senior/19

Lipsitz, George. 2007. “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape.” Landscape Journal 26 (1): 10–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43323751.

McMahon, K. “Broadband: Survey of Planners and Best Practices”. Practicing Planner. Vol. 11, No. 3 (2013)

New York City Department of Education. n.d. The IEP Process. NYC Schools. Accessed May 2025. https://www.schools.nyc.gov/learning/special-education/the-iep-process/the-iep.

New York City Department of Education. 2019. Annual Special Education Data Report: School Year 2018–2019. New York: NYC Department of Education. https://infohub.nyced.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/annual-special-education-data-report-sy18-1960b79998ec27487584b9fedec3fac29c.pdf.

New York City Department of Planning, NYC Capital Planning Explorer, https://capitalplanning.nyc.gov/facilities.

Piggott, Charlotte L., Chris M. Spray, Claire Mason, and Daniel Rhind. 2024. “Using Sport and Physical Activity Interventions to Develop Life Skills and Reduce Delinquency in Youth: A Systematic Review.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2024.2349994.

Raj, Chiraag S. 2022. “Rights to Nowhere: The IDEA’s Inadequacy in High-Poverty Schools.” Columbia Human Rights Law Review 53 (2): 409–440. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2463&context=law_facpub.

Riley, Trevon, Joseph P. Schleimer, and Julia L. Jahn. 2024. “Organized Abandonment under Racial Capitalism: Measuring Accountable Actors of Structural Racism for Public Health Research and Action.”

Shippen, Nicole, Samantha R. Horn, Patrick Triece, Andrea Chronis-Tuscano, and Maggie C. Meinzer. 2022. “Understanding ADHD in Black Adolescents in Urban Schools: A Qualitative Examination of Factors That Influence ADHD Presentation, Coping Strategies, and Access to Care.” Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 7 (2): 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.2013140.

Torrens, Paul M. “Wi-Fi Geographies.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98.1 (2008): 59-84