Occupation through Smart Cities

Artsakh, or Nagorno-Karabakh, is a region of the Caucasus that has been the site of particularly violent contestation between Armenian and Azerbaijani ethnolinguistic groups since the decline of the Soviet Union, first from 1988 to 1994 resulting in occupation of the historically majority-Christian and majority-Armenian-ethnolinguistic region by Azerbaijani military, then in 2020, with the subjugation of this population to governance by the Azerbaijani state, and finally, in 2023, with a state program of depopulation, including forced expulsion of over 120,000 Armenian residents and the coerced surrender of national identity of remaining residents.

Before focusing on “smart cities”, it is important to critically address how the tactics used by the Azerbaijani nation-state to consolidate control over this area closely parallel the Azerbaijani nation-building project. A tactic is the deployment of “ecological activists” to blockade the Lachin Corridor. Claiming to protest pollution and a vague risk of environmental exploitation, these “activists” prevented delivery of supplies or personnel to majority-Armenian areas. Nonetheless, in 2021, Azerbaijan intervened in the Qashgachay, Elbeydash, and Agduzdag ore deposits, subsequently selling land to Turkish mining companies. Here, too, one reads an underlying anxiety about Azerbaijani dependency upon a petroleum economy quickly falling out of vogue on an international stage. Coincidentally, Azerbaijan also began its development of “the biggest solar park” in Garadagh with the statement of using “clean air energy”, adding to their greenwashing roles.

In line with the Azerbaijani nationalist claims to the dual authorities of an ancient empire and a contemporary, technocratic futurism, “smart cities” have emerged as a 21st-century, greenwashed settler-colonial tactic. Variously described as “integrated with advanced technologies to enhance urban and rural living conditions” or simply surveillance state apparati, “smart cities” have been built throughout Azerbaijan, but most recently in “liberated” Karabakh as a means of consolidating control over the territory.

This list of case studies is not comprehensive, with the following cities being notably omitted due to present limitations on information access:

- Khojavend

- Shusha

- Soltanli

Alirzah, Aghadzor, Aghali I, II, III

high speed internet, smart street lights, video link government services ("DOST"), occular scanning (medical)

Agali I, II, and III, are a collection of settlements in the Zengilan region and perhaps the most emblematic of the historical entanglements of all of the smart cities of the former Artsakh area.

The city's impressive post-2020 construction with integrated "smart technologies" presents an interesting paradox for Azerbaijani state mythmaking. On one hand, the city is "new," built from the ground-up with 21st-century technologies, and yet, on the other hand, it must appear "old," so as to warrant its "liberation" from ethnic Armenians in the project of "the Great Return".

President Aliyev's tweet announcing the city's "recapture" already hints at a certain awkardness, identifying Agali I, Agali II, and Agali III as "liberated" towns:

Müzəffər Azərbaycan Ordusu Zəngilanın Birinci Ağalı, İkinci Ağalı, Üçüncü Ağalı, Zərnəli, Füzulinin Mandılı, Cəbrayılın Qazanzəmi, Xanağabulaq, Çüllü, Quşçular, Qaraağac,

— İlham Əliyev (@azpresident) October 28, 2020

In truth, like many other caucasian cities, Agali's history comprises a palimsest of names and residents better read in reverse chronological order. Just prior to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, the city, then called "Aghadzor," was home to a majority population of ethnic Armenians. Even as of 2025, videos of Aghadzor street signs or restaurants can be found online. Further back, during the establishment of the Republic of Artsakh and the fall of the Soviet Union, a 1992 CIA linguistic study identified the area as populated, but with no dominant linguistic group, likely a mix between Azeri Turkish and Armenian. Then, going back to 1962, Soviet administrative maps show the area belonging to the general administrative region of Zengilan in the Azerbaijan SSR.

As of writing, no evidence is known to the authors of this site of the name "Agali" prior to the Soviet Union, though its pre-Soviet historical name "Alirzah" does imply a Persian or Turkic-language-speaking population. The ambiguity of this city's origin does not accept the facile ethnonationalist identification of the city, but rather demonstrates the city as something that predates the very invention of nationhood. Ironically, it is precisely the possibility of this city having potentially Turkic origins as Alirzah that makes its renaming as Agali so necessary for Azerbaijan. This is because, counterintuitively, if the linguistic history of the city is to be accepted, then it must be furthermore accepted that supposed linguistic borders do not follow the ethnonationalist borders presently claimed by the Azerbaijani state. Agali, therefore, can only ever be seen as "old enough," but not an ancient metropolis like Baku or Fuzuli.

This perhaps places greater emphasis on the role of the "smart technologies". Indeed, Aliyev's tweet about Agali I, II, and III is perhaps less about a truly historical claim and more about the World Bank's smart city report published earlier in 2020. One must note, however, that with the exception of the "smart street lights", the technologies that make Agali "smart" are in fact quite ubiquitous among other cities across Azerbaijan. Most technologies, including the notable video-based government services, are managed through Əmək pensiyası və sosial müavinətlər (DOST), a state agency for social welfare. Agali is, at its core, a housing project, part of the program of "repatriating" 100,000 Azerbaijani citizens at the cost, no less, of 130,000 displaced ethnic Armenians.

The smart street lights, meanwhile, suggest a different set of priorities in designating the city as a "smart city". Visible in the video below, the lamps bear substantial resemblance to Huawei Smart Poles. While further investigation is needed to confirm the sourcing of these lamps, "smart city technologies" have elsewhere proven instrumental in China-Azerbaijan relations.

The instrumentality of Agali's "smart city-ness" thus reveals three anxieties. From a historical point of view, the designation smart city provides a means of subverting question that may undermine some of the more tenuous historical claims to an ancient Azerbaijani nation state. Second, the city's "intelligence" offers something of a techno-propagandistic surplus that avoids the uncomfortable conclusion that the city's role in housing people necessarily starts with a deficit of houses. Third, the city's specific technologies provide economic opportunities, not only to request loans from the World Bank, but to improve trade relations with foreign partners such as China and Israel.

Technologies deployed:

to be determined, likely the same as Agali

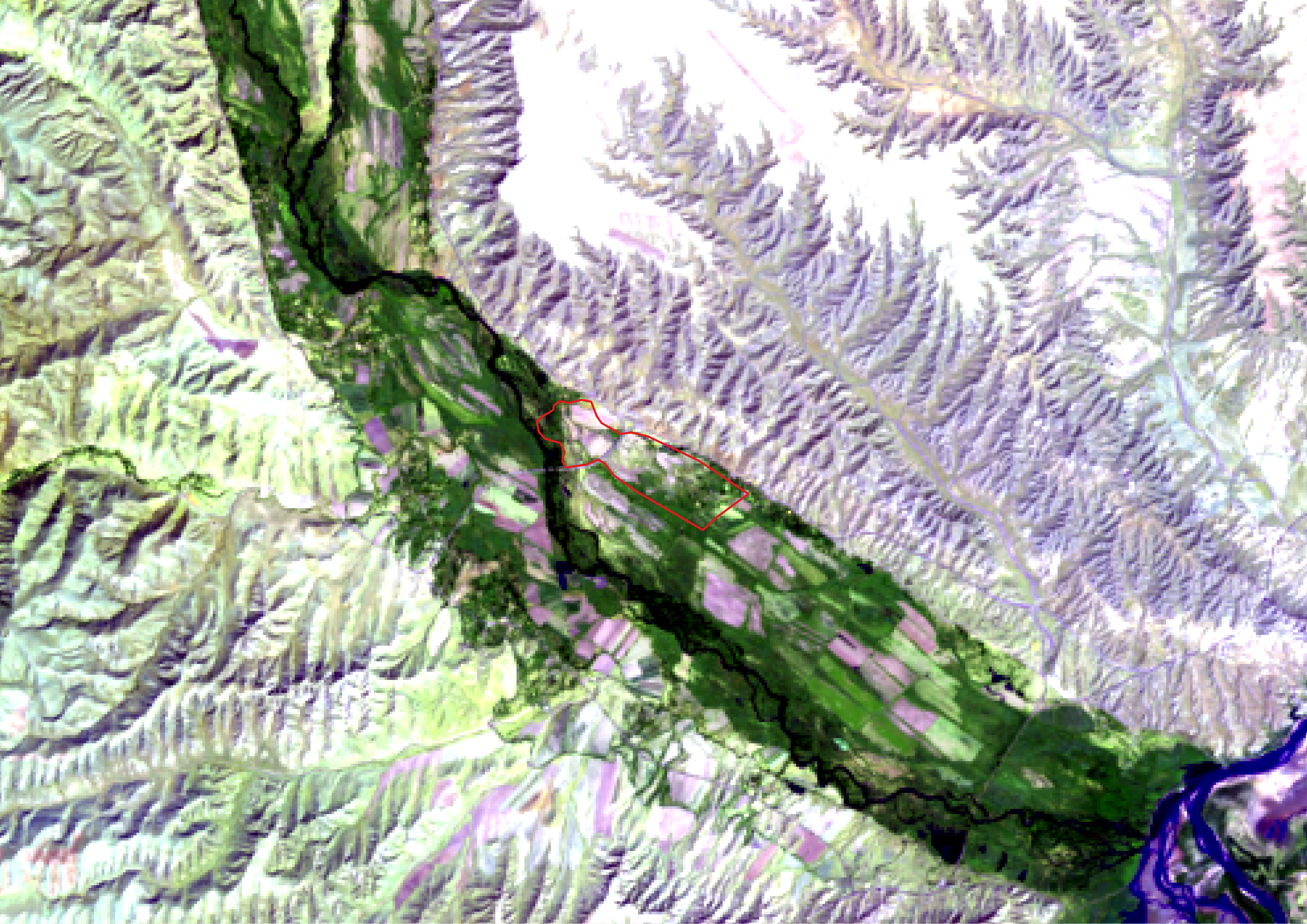

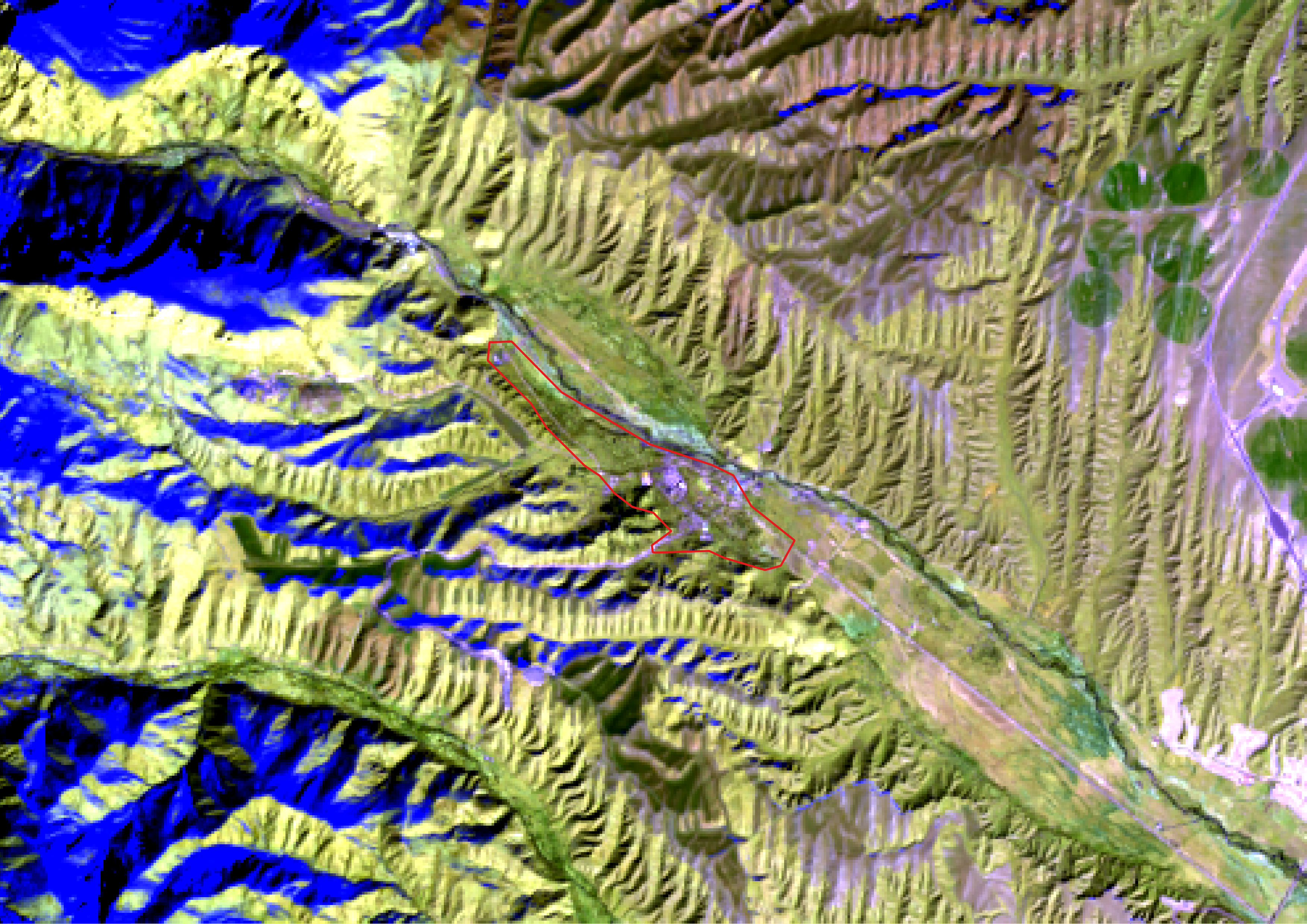

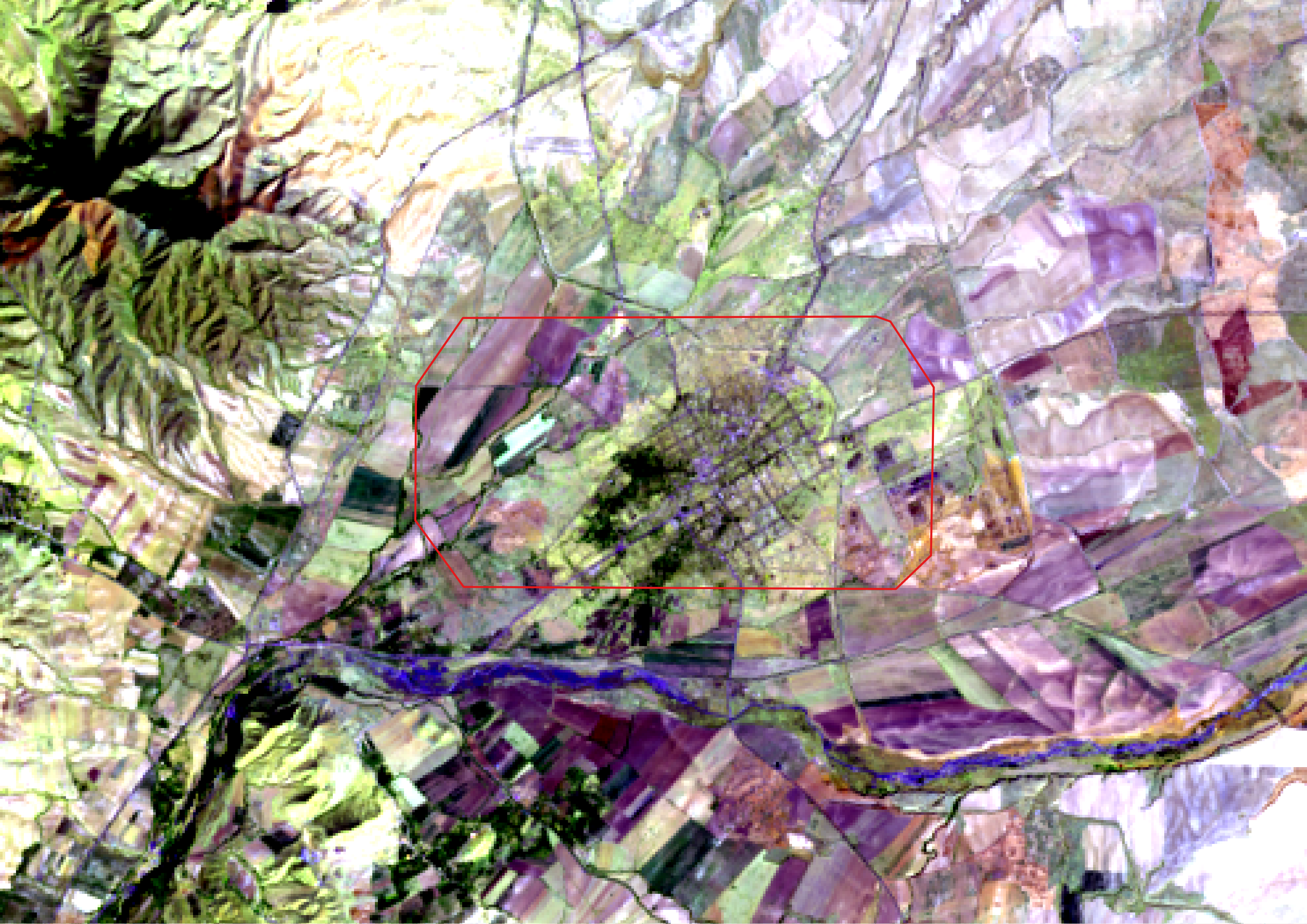

Though most mentions of Zengilan as a "smart city" refer instead to Agali I, II, and III, towns considered within the broader metropolitan area of Zengilan, recent developments in Zengilan, as seen in the false color satellite imagery, may suggest a new phase in the development of the "smart city" concept. In particular, the Zengilan-Agali relationship demonstrates the state distinction of "smart cities" and "smart villages". Though the 2020 World Bank proposal for Smart Cities in Azerbaijan (as well as the 2023 follow-up report by the same) do not make any distinction between Smart Cities and Smart Villages, some effort has been put into to distinguishing the two terms in official state communications.

On its surface, it appears that the distinction may refer to a slight difference in infrastructural focus on urban versus agricultural technologies, but firsthand accounts by Azeri farmers in Agali suggest otherwise, noting the city's prohibition on keeping livestock too close to the city. Instead, the distinction may be a more procedural one, with "smart villages" serving as experimental branches attached to "smart cities". The later developments of Zengilan compared to the rapid development of Agali may corroborate this claim.

That the "smart city" concept is one that remains in flux is a fairly uncontroversial claim. What is curious, however, is that the World Bank smart city concept (published just prior to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War) was deployed fairly quickly before the officially proposed deployment in the Zengilan "smart city". The term "smart village" here serves a secondary role-to grant some plausible deniability to the World Bank and pre-October 2020 leadership for a program of total depopulation of Artsakh. To clarify, the point of this statement is not to argue that the World Bank had any direct role in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War; rather, it is to point out the fact that the legal claim of Azerbaijan on the area is not entirely tenable in purely contemporary terms of international law, and that the claim to Zengilan and Agali must draw both from the historical "authenticity" of Zengilan and the technological spectacle of Agali without fully admitting the mutual insufficiencies of the individual cities.

Like with Zengilan and Agali, Jebrayil is also structured along the "smart city-smart village" concept, with most initial developments occuring in the smart village of Soltanli. Unlike Zengilan and, however, the "smart technologies" cited in the region are primarily infrastructural, including the solar farms as well as the construction of the Horadiz-Agband trainline running across the Zangezur Corridor (presently running through Armenian territory), connecting Fizuli and the larger Nakhchivan region.

As published by Azerbaijani state media, the groundbreaking ceremony for Soltanli village was attended by Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Péter Szijjártó and coincides with the 2023 STRING oil and gas agreement between Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia. The designation of Jebrayil as a "smart village" does not refer to any present technological innovation, but rather to an aspiration of future conquest of the Zangezur Corridor currently within Armenian borders, which, if conquered, might appear simply as the continuation of a longstanding transnational development program.

Technologies deployed:

"green energy initiatives", waste treatment, water monitoring, "construction of houses from natural materials... involves the use of smart technologies", solar heat pumps, charging stations, solar collectors, solar parking lots

The historic city of Agdam, recognizable in maps predating the earliest mention of Azerbaijan or the birth of pan-Turanist ideology, plays a critical role in contemporary definitions of Azerbaijani nationalism. The city maintains an undeniably Turkic heritage and, like the similarly historic Fizuli, suffered immensely during the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, earning the bleak moniker "the Hiroshima of the Caucasus" after being entirely depopulated of its almost 30,000 ethnic Azeri residents.

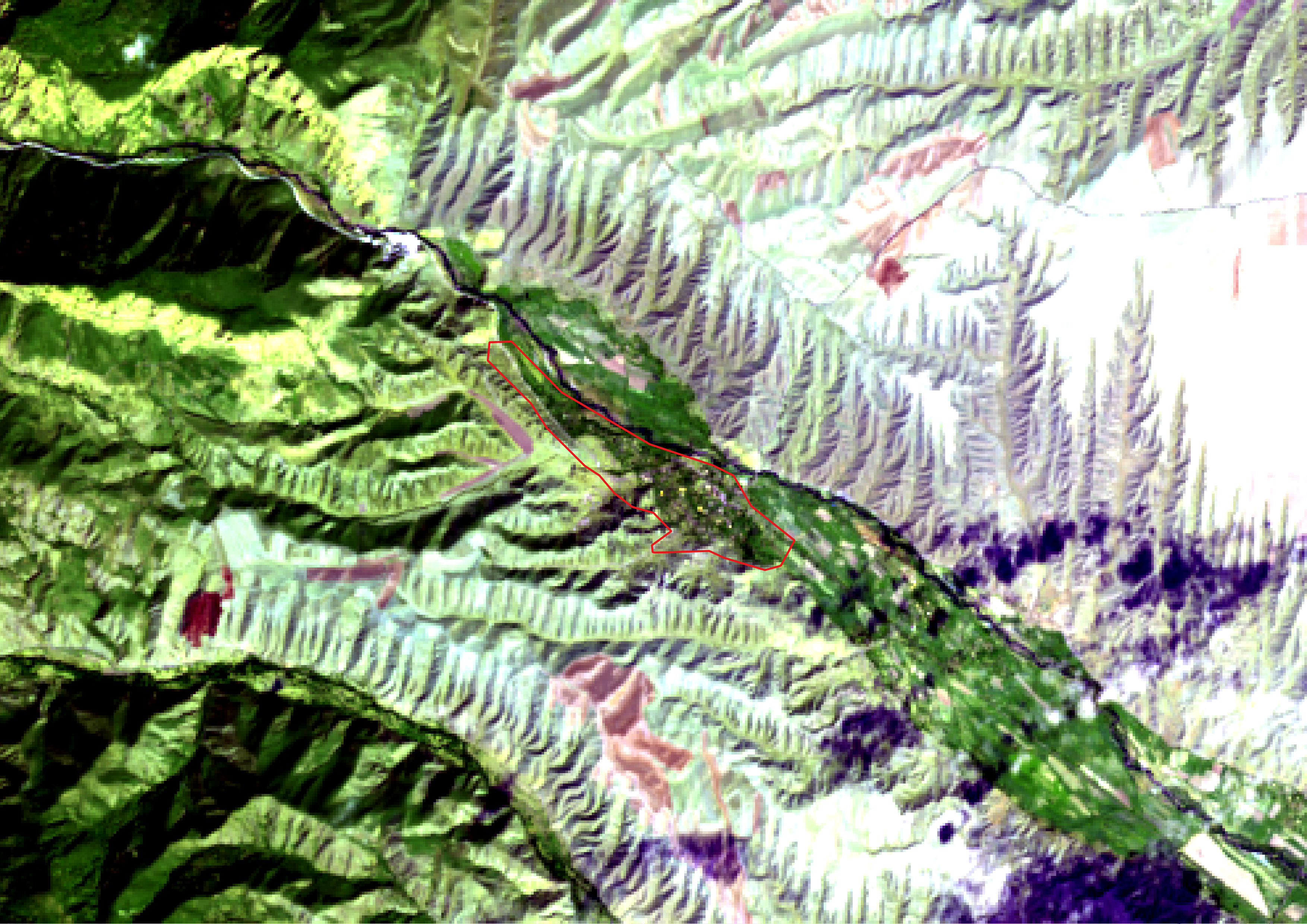

Agdam, in many ways, represents both the most sincere of Azerbaijan's claims to Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh as well as its most cynical. On the sincere end, actions like the 2024 restoration of the Agdam Mosque and the vast resources dedicated to demining the never-fully-repopulated city allows the 21st-century Azerbaijani state to position itself as a steward of Ottoman/Turkic heritage in a manner that even Agali or Baku do not fully satisfy. The master planning visible in the false color satellite imagery, for example, may not simply be a Haussmannian rewriting of history, but rather unironically inspired by the material constraints of contaminated water and landmine placement.

Nonetheless, given the city's history and the apparent ease with which it may fit into nationalist victimhood, it may be curious that relatively little forensic attention has been granted to the historical city in comparison to the press given to its recent "smart city" developments. It is here that the more cynical side of Agdam's reconstruction reveals itself.

Studies of damage to Agdam, while revealing of individual war crimes perpetrated by Armenian military and paramilitary against civilians, presents as far less hateful than typically categorised. The story of the desecration of the Agdam Mosque and its subsequent use to house cattle, for example, may have been largely exaggerated beyond a simpler reality of material neglect in a depopulated area. Furthermore, traces of BM-21 artillery suggest Agdam's use as a military installation by Azerbaijani forces during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Agdam's 20th-century history is undeniably tragic, but the magnitude of its destruction does not indicate Armenian intentions to perpetrate genocide beyond a cruel (and illegal) eye-for-an-eye calculus characteristic of the first Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Viewed from a more 21st-century perspective, Agdam's construction is presently ongoing (as of May 2025) and now relies heavily on collaboration with Slovakia. Though further investigation is required into the outcomes of the alleged green energy initiatives proposed as part of the "smart city" designation of Agdam, one curious fact is that much of this "green" infrastructure is being installed with the support of the Solidarity Ring (STRING) Project. STRING, an agreement to enable natural gas and oil deliveries to Europe, may instead suggest a core anxiety about the Azerbaijan's (and other member states') anxieties about their own economic dependency upon fossil fuels rapidly falling out of favor on an international stage.

Technologies deployed:

solar panel

Technologies deployed:

smart water management, renewable energy production, bioenergy, energy storage systems, energy-efficient buildings, smart grids, hydropower

Fuzuli also follows a model of "smart city-smart village"; the town of Dovletyarli was named as a nearby "smart village" making extensive use of solar power.

____

Bibliography

(Secondary sources)

“Azərbaycan Respublikasının Qaşqaçay, Elbəydaş Və Ağduzdağ Filiz Yataqlarının Öyrənilməsi, Tədqiqi, Kəşfiyyatı, Işlənməsi Və Istismarı Ilə Əlaqədar Bəzi Məsələlərin Tənzimlənməsi Haqqında Azərbaycan Respublikası Prezidentinin Sərəncamı » Azərbaycan Prezidentinin Rəsmi Internet Səhifəsi,” May 29, 2021, https://president.az/az/articles/view/51802.

Babayan, Melsida. “Urbanism and Infrastructure as Military Weapons in Artsakh.” The Funambulist Magazine, no. 50 (October 25, 2023). https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/redefining-our-terms/urbanism-and-infrastructure-as-military-weapons-in-artsakh.

International Institute for Environment and Development. UN Climate Change Conference COP29. Accessed May 2, 2025. https://www.iied.org/collection/un-climate-change-conference-cop29.

Nas Daily. "The first oil country is Going Green." TikTok, October 30, 2024. https://www.tiktok.com/@nasdaily/video/7431552292815539474

“President of Azerbaijan and First Lady Attend Opening of ‘Azerbaijan’s Contribution to the World of Culture’ Exhibition.” President.az. Accessed March 5, 2025. https://president.az/en/articles/view/53249.

TRT World. “Azerbaijan Unveils Karabakh Smart Village,” September 27, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oV7pfopkMCg.

Visit Every Country (@visiteverycountry). "Free house in Karabakh? Welcome to the Agali Smart Village in Azerbaijan 🇦🇿 #agali #karabakh #zangilan #azerbaijan🇦🇿 #visiteverycountry #travelstories #refugees" TikTok video, 1:27. Posted September 15, 2022. https://www.tiktok.com/@visiteverycountry/video/7143519832514907397?_t=ZT-8uTMC4H6kw6&_r=1.

(Primary sources)

Huseynova, Zumrud. “Smart Village and Smart City Project in the Social Policy of the Republic of Azerbaijan.” Ancient Land International Online Scientific Journal 29, no. 3 (2025): 38-44. https://doi.org/10.36719/2706-6185/29/38-44.

Uni Assistance. “Smart Qarabag: Smart Village - Qarabag”. 2021.

World Bank. Smart Villages in Azerbaijan: A Framework for Analysis and Roadmap. June 2021.

(Datasets)

Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. (2020). Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager / Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-2, Collection 2 [LC08_L2SP_168032_20200830_20200906]. U.S. Geological Survey.

Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. (2020). Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager / Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-2, Collection 2 [LC08_L2SP_168033_20200915_20200919]. U.S. Geological Survey.

Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. (2025). Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager / Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-2, Collection 2 [LC08_L2SP_168032_20250305_20250312]. U.S. Geological Survey.

Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. (2025). Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager / Thermal Infrared Sensor Level-2, Collection 2 [LC08_L2SP_168033_20250305_20250312]. U.S. Geological Survey.

World Bank. Smart Villages in Azerbaijan: A Framework for Analysis and Roadmap. June 2021.

Geospatial World. "Nagorno-Karabakh Exodus: Satellite Images Capture Mass Migration." Geospatial World, accessed February, 2025. https://geospatialworld.net/prime/nagorno-karabakh-exodus-satellite-images-capture-mass-migration/.

Humanitarian Data Exchange. HOTOSM Azerbaijan Roads (OpenStreetMap Export). Accessed May 9, 2025. https://data.humdata.org/dataset/hotosm_aze_roads.