The Ever-changing City: Rethinking the Role of Informality in Jakarta

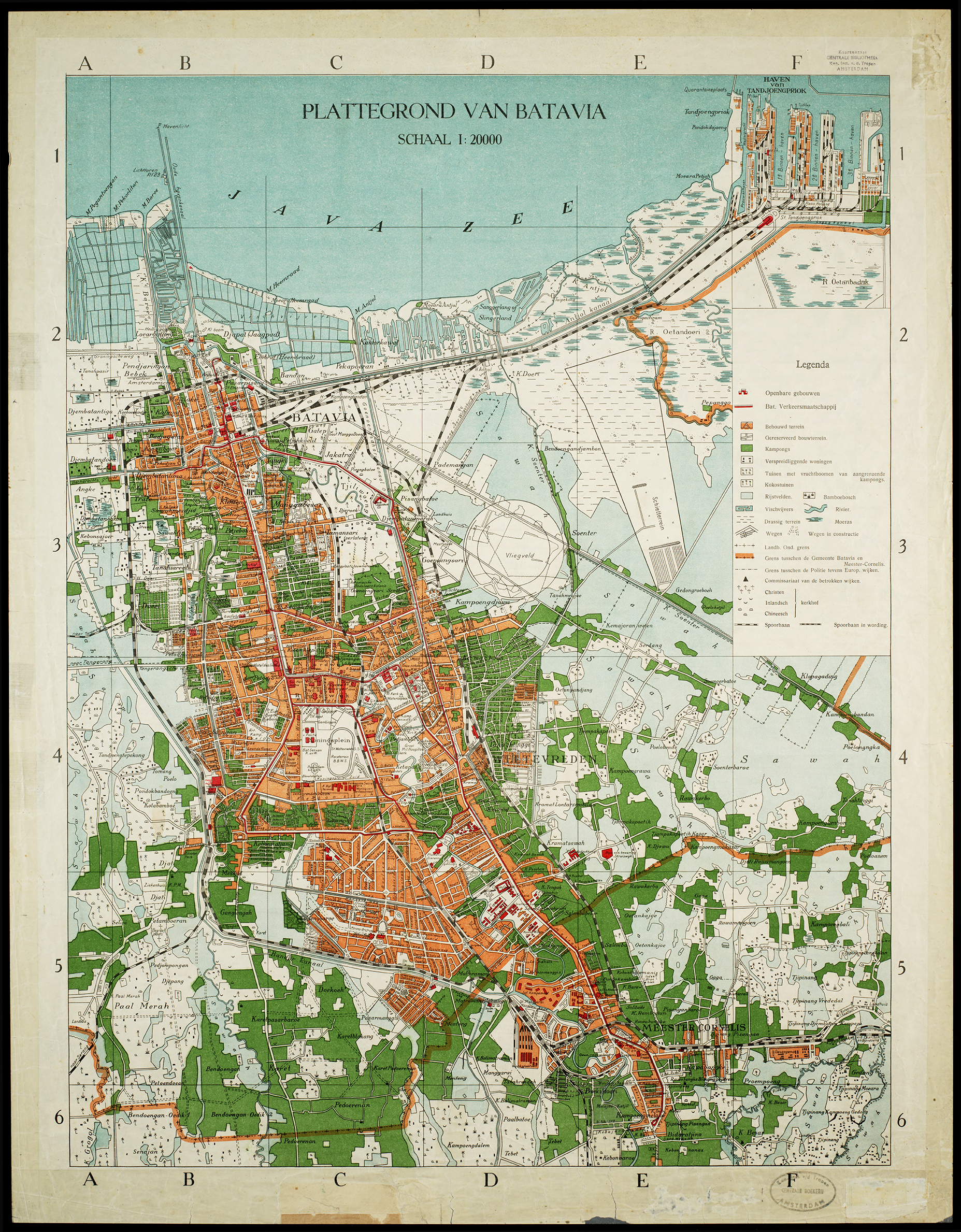

Fig.1 - Plattegrond Van Batavia, 1938 - red color denotates built areas while green color denotates kampung areas. (Source: Leiden University)

Fig.1 - Plattegrond Van Batavia, 1938 - red color denotates built areas while green color denotates kampung areas. (Source: Leiden University)

Introduction

the long-standing paradigm that categorizes Southeast Asian cities as “Third World cities” with unique, non-Western features. Dick and Rimmer (1998) argue that due to globalisation and urban restructuring since the 1980s, Southeast Asian cities are increasingly converging with Western urban forms. Cities now feature edge cities, gated communities, mega-malls, and integrated satellite towns, especially around Jakarta. Jakarta exemplifies hybrid urban conditions, with new town developments reshaping the urban landscape into sprawling, privately developed zones integrating residential, commercial, and industrial functions, where informal settlements (kampung) are not peripheral but integral to the city’s form and function. This challenges the dominant urban theories focused on formal development and marginalization. Kampungs embody a “middle” position—both rural and urban, formal and informal, integrated yet marginalized.

Informal settlements or kampungs are home to 20–25% of Jakarta’s population and are often labeled “illegal” by authorities. Residents face both environmental threats (flooding, subsidence) and state-led displacement via “modernization” plans like river dredging and flood mitigation. The state simultaneously depends on and displaces kampung residents, using evictions and redevelopment as tools of control.

Jakarta’s urban form is best understood not through binary oppositions but via the integrated, ambivalent space of the kampung—a site of survival, negotiation, and production within capitalist urbanization.

The Sprawling Metropolis

Who has the right to author a city? Throughout its history, the development of Jakarta has emerged as an interplay of socioeconomic forces. From its origin as a Dutch colonial city to its eventual zenith as one of the most populated cities in the world. Because of that, Jakarta doesn’t have a fixed urban identity as its development goals change to suit its political landscape. One constant that’s ever-present is the existence of informality. Be it in the form of kampung or informal economy, informality has been the ongoing thread that connects Jakarta’s past, present, and future.

Despite its perseverance, the residents of Kampungs in Jakarta face constant fear of forced eviction by the government. Often understood as dirty, disorganized, or hurtful to the image of the city, many kampung areas are demolished in favor of building infrastructure or political projects such as riverbank development, city stadium, or luxury housing. Worse yet, the Kampung residents are not temporary squatters. They’re often long-time, multi generational families who work in the city as street vendors, cleaners, domestic workers, uber drivers, and more. The evictions disrupt their socioeconomic stability and often reverberate into violent conflicts with the authority, worsening their image to the public.

It is unfortunate that informality often framed as thorns that should be trimmed in Jakarta’s contemporary urban development. With so many forced eviction, on will wonder why such an integral part of a city’s history is constantly demonized. A dialogue with RRJ (Rame-Rame Jakarta), an NGO specializing in championing informality in Jakarta revealed an insightful perspective to this issue.

The Western Idea of Urbanization

Urban development in Jakarta increasingly reflects a globalized, Western-influenced mindset—one that prioritizes top-down planning, technological efficiency, and alignment with international standards of modernity. Initiatives such as the Jakarta Smart City program and the city’s aspiration to become a global financial hub are emblematic of this trend. They frame progress in terms of digital infrastructure, economic competitiveness, and investment appeal, often designed and delivered through elite-driven governance.

A striking example of this mindset is the Great Garuda project (NCICD)—a Dutch-led mega-infrastructure plan that proposes to shield Jakarta from coastal flooding through a massive sea wall shaped like a mythical bird. Marketed as both a flood solution and a symbol of national advancement, the project also includes land reclamation and luxury development.

As Kian Goh notes in Form and Flow, the Great Garuda functions not only as engineering but as a narrative of state-led modernization—one that has been heavily criticized for privileging elite interests, justifying kampung evictions, and excluding meaningful public participation.

Together, these initiatives illustrate how urban transformation in Jakarta often relies on a Western logic of control and formalization, where communities are expected to adapt to the plan, rather than shape it. To move toward a more equitable and inclusive city, development must shift from imposing visions from above to recognizing and engaging the urban knowledge that already exists on the ground.

Tracing the History of Jakarta Political Dynamics

Jakarta has long been more than just Indonesia’s capital—it has been a launchpad for political power. Over the past two decades, the role of governor has increasingly become a pathway to the presidency. In this context, large-scale urban development projects—flood mitigation, housing renewal, infrastructure upgrades, are often used not just to address urban challenges, but to perform leadership and gain national visibility.

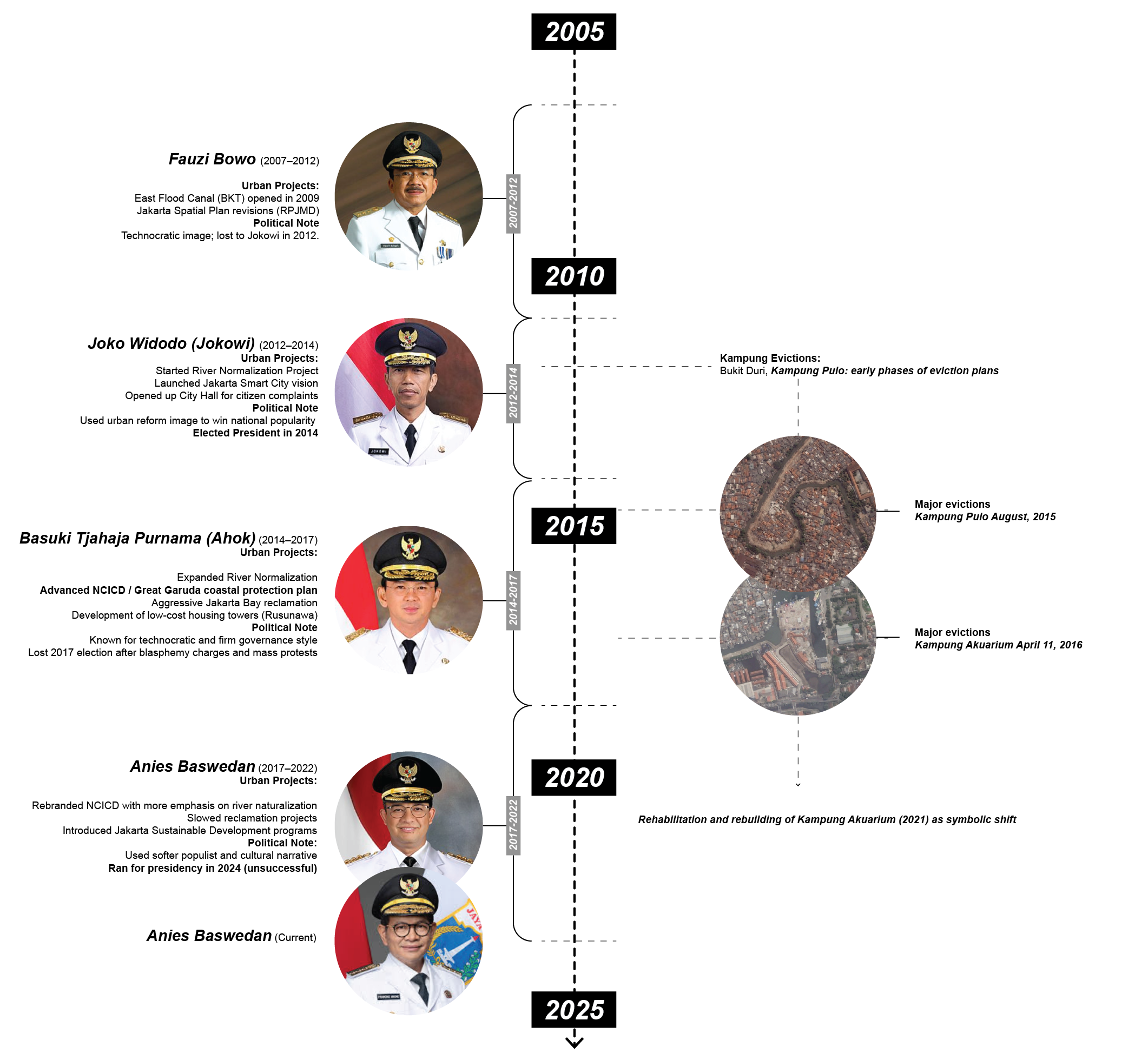

Fig.2 - Timeline of Jakarta’s Political and Urban Development History (2007–2022)

Fig.2 - Timeline of Jakarta’s Political and Urban Development History (2007–2022)

From Sutiyoso and Fauzi Bowo to Jokowi, Ahok, and Anies Baswedan, each administration has introduced its own wave of mega-projects: river normalization, seawalls, smart city platforms, and expressways. While framed as solutions to pressing urban issues, these projects often reflect top-down decision-making shaped more by political ambition than by local needs. Jokowi’s rise, for example, was closely tied to his urban initiatives in Jakarta, many of which were continued or intensified by his successors.

Across these shifts, kampung communities have borne the cost. Evictions often rise during periods of political transition, revealing how Jakarta’s landscape is not only a site of planning, but of power. The ever-changing city reflects not just development pressures, but the ambitions of those who hope to rule it, and beyond.

The Forgotten Crises

The politicization of kampungs in Jakarta has caused deep wounds. From a loss of neighborhood bonds, intergenerational care, and support networks, many residents have expressed deep regret at the destruction of their homes. The psychological impacts are rarely discussed, too. Ranging from feelings of shame, alienation, and trauma, these forced evictions become the source of stress to an already marginalized community. The trauma is especially unique as the emergent nature of Kampung’s dense network is hard to build as it relies on informality, an aspect that the government demonizes.

With its westernized development compass, the government often replaced these organically formed Kampung with flats and social housing that is built based on formality. While it can handle the population density of a kampung, it is lacking in its capacity to handle its cultural density.

”In a flat, there is no neighbor. In kampung, we live together”--- Kris, RRJ

What is the proper approach in integrating kampung into Jakarta’s contemporary paradigm? To investigate this issue, we must first understand the different relationship between kampungs and Jakarta. In this study, three kampungs are selected as case studies to observe these relationships. Those kampungs are Kampung Pulo, Karbela, and Kampung Akuarium.

Case Studies

Kampung Pulo: Wiped out in the name of flood control

Kampung Pulo was a dense riverside neighborhood in East Jakarta, situated along the Ciliwung River. Despite being informal in the eyes of the state (many lacked formal land ownership), Kampung Pulo was a well-organized, socially connected community and tight-knit social life made it a place of belonging for working-class Jakartans.

Fig.3 - Timelapse satellite images of Bukit Duri and Kampung Pulo reveal the shift from informal waterfront settlements to a hard-engineered riverbank.

Fig.3 - Timelapse satellite images of Bukit Duri and Kampung Pulo reveal the shift from informal waterfront settlements to a hard-engineered riverbank.

In August 2015, the Jakarta provincial government under Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) carried out a large-scale forced eviction of Kampung Pulo residents.

The government claimed the eviction was necessary for:

- Ciliwung River normalization (flood control and infrastructure improvements)

- Creating a green corridor and embankment wall

- Protecting Jakarta from annual flooding

Despite widespread protests, many residents were evicted with little warning or fair compensation. Hundreds of police and military officers were deployed. Heavy machinery moved in, demolishing homes while people were still packing their belongings.

Kampung Karbela: Strategic Location = Daily Interaction

Karet Kuningan, or Karbela, sits in the shadow of Jakarta’s Golden Triangle—one of Southeast Asia’s most important financial districts. Its presence highlights the strategic location of many kampungs, which have evolved alongside the city over time.

Fig.4 - Timelapse satellite images show the transformation of the financial district and Kampung Karbela.

The red overlay represents the officially recognized area of Kampung Karbela, while the yellow dashed boundary marks the edge between the kampung and the financial district, where commercial activity and interaction is concentrated.

Residents of Karbela operate a wide range of informal services that directly support workers in the financial district, illustrating the deep interconnection between kampung life and Jakarta’s formal economy. These residents provide essential, low-cost labor across various sectors, including:

- Street food stalls and warungs that feed thousands of office workers each day.

- Laundry and tailoring services catering to white-collar staff.

- Parking management, motorbike taxis (ojek), delivery services, and domestic work for nearby executives.

- Kampungs offer affordable housing in the city, housing a large portion of Jakarta’s working-class population, despite overcrowding and poor infrastructure.

Fig.5 - Timelapse of Google Street View images at the edge of the area shows transformation where informal services are actively operating

Fig.5 - Timelapse of Google Street View images at the edge of the area shows transformation where informal services are actively operating

These services are not only affordable and flexible, but they also rely on hyper-local knowledge—making them vital to the smooth operation of Jakarta’s formal economy. Far from being separate, they are deeply interwoven into the systems that keep the city running.

"Their survival isn’t just about resistance, it’s about co-production of the city."

Kampung Akuarium: Erased ,but rebuilt by resistance, the best approach to accommodating informality

Kampungs Residents had lived in the area since the 1970s, forming a tight-knit community with livelihoods tied to the nearby fish market and informal economic activities. They preserve cultural traditions, creating strong community networks and social support systems, while contributing to the city’s unique cultural identity in this fisherman community.

Fig.6 - Timelapse satellite images of Kampung Akuarium transformation

Like many kampungs Akuarium established near trade routes, water sources, or urban centers for economic and resource access. Over time, these locations became valuable real estate, and Kampungs remained in place as cities expanded. On April 11, 2016, the Jakarta Provincial Government, under Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok). The eviction aimed to revitalize the Kota Tua heritage area and integrate the land into urban development projects.

Fig.7 - Timelapse of Google Street View images shows transformation of the contested site where residents refused to relocate and stayed in makeshift shelters.

Fig.7 - Timelapse of Google Street View images shows transformation of the contested site where residents refused to relocate and stayed in makeshift shelters.

Following the eviction, many residents refused to relocate to temporary housing and instead stayed in makeshift shelters on the demolished site. They organized protests, filed lawsuits, and garnered support from NGOs. Which are another form of infrapolitic, daily tactics: rebuilding demolished homes, resisting registration to remain off radar, reclaiming public space. After Anies Baswedan’s election victory, the government initiated the reconstruction of Kampung Akuarium as a “vertical kampung”—a mid-rise housing complex designed with community input.

“Warga beradaptasi dengan cara yang tidak terlihat, tapi sangat politis.” Kampung resistance ranges from visible protest to infrapolitical acts

Conclusion and Hopes for the Future

The story of Jakarta’s kampungs reveals a deeper imperative: Southeast Asian cities must be reintegrated into global urban discourse not as passive recipients of Western planning models, but as producers of their own urban knowledge. Too often, dominant frameworks prioritize formal infrastructure and top-down control, sidelining the lived realities of communities whose informal systems are deeply adaptive, resilient, and socially rich. Kampung residents do not reject development. They call for in-situ upgrading, secure tenure, and hybrid spaces that sustain social proximity and everyday livelihoods. As one resident put it,

"Warga ingin kota yang bisa menampung hidup mereka, bukan mengusir mereka” —they want a city that can hold their lives, not push them out."

Researchers, activists, and design practitioners working in solidarity with these communities envision a different urban future—one that challenges narratives that criminalize informality and instead positions it as a site of innovation, care, and collective life.

The kampung is not a remnant of the past but a living alternative to dominant urban paradigms. If global urban discourse is to respond meaningfully to the intertwined crises of inequality and climate change, it must shift from exporting solutions to learning from situated practices. In the kampung, we find not a problem to solve, but a set of propositions for how cities might be reimagined just, adaptable, and rooted in the lives of those who build and sustain them every day.

References

Dick, H. W., and P. J. Rimmer. “Beyond the Third World City: The New Urban Geography of South-East Asia.” Urban Studies 35, no. 12 (1998): 2303–2321. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098983985.

Kusno, Abidin. “Middling Urbanism: The Megacity and the Kampung.” In Visual Cultures of the Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, 163–180. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2020.

Goh, Kian. Form and Flow: The Spatial Politics of Urban Resilience and Climate Justice. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12801.001.0001.

Rame-Rame Jakarta. Personal interview by Bimo Wicaksana and Dolyagritt Wonggom, via Zoom, March 29, 2025.

Jakarta Smart City. “Mengenal Konsep dan Pengertian Smart City.” Accessed May 1, 2025. https://smartcity.jakarta.go.id/en/blog/mengenal-konsep-pengertian-smart-city.

Jakarta Smart City. “Upaya Jakarta Menuju Kota Global.” Accessed May 1, 2025. https://smartcity.jakarta.go.id/en/blog/upaya-jakarta-menuju-kota-global.