Deproblematizing Flooding by Problematizing the Waterfront

We Picked the Wrong Fight!

What is the waterfront? Images of beaches, docks, and promenades come to mind – recreational space lulled by the sound of crashing waves. The water ebbs and flows as the surface shifts, lapping at the shore. Our intuition understands the waterfront as a dynamic space of ever-changing waves and tides; so why then, do our maps define our waterfront with static lines? Water will always escape the neat boxes we draw to contain it.

While our maps are representations of space, they hold real consequences. Mapping acts as a tool for urban and environmental planning to shape space. The abstract lines we draw eventually materialize through the infrastructures we build. Along coastlines, this looks like seawalls, berms, bulkheads, docks, breakwaters, and levees, all designed to define where water can and cannot go. When waters shift (as with climate change) or exceed predictions (as with Hurricane Sandy), our neat lines quickly dissolve. The government holds protocols to protect against these events through form codes and insurance. This relationship, however, positions flooding as the problem, not the overextended development which it threatens. This is the urban waterfront of today.

In recent decades, urban designers and ecologists have challenged traditional conceptualizations of the waterfront, attempting to soften urban edges by promoting green infrastructure like horizontal levees or marsh restoration to mitigate flood risk. These projects invite room for the movement and capture of water, largely learning from Dutch methods of flood adaptation. Softening lines and mediating hydrologic systems has proven effective. However, the logic of applying Dutch technique to New York – a former Dutch colony – positions these methods as inherently colonial.

This project seeks to use critical cartographic tools to map these competing conceptualizations of the water-land interface to challenge the governmental and scientific definitions by which water is problematized. Across these competing definitions, we explore the idea of the extent to which historic, legal, and scientific waterfront delineation is more so a product of judgement through methodology than of actual natural ebbs and flows of water. As a counternarrative, we will highlight indigenous ontologies and epistemologies for living with water that survive in storytelling and language. We use Jamaica Bay in New York City as a geographic case study of the ways in which these frameworks create or deproblematize flood exposure.

To accomplish this, we expect to use a mixed-methods approach. Colonial conceptualizations of the waterfront draw from institutional datasets like FEMA flood maps, shoreline clipped boundaries, tidal datums, sea level rise projections, and historical maps. Indigenous Lenape conceptualizations draw from language, oral history and storytelling, and archaeological evidence that demonstrate a different conceptualization of the water-land interface. These competing narratives are visualized in a series of maps that challenge Western definitions of waterfronts.

How do the lines we draw enact violence upon people and nature? And what alternatives can we learn from?

The Power of the Line

Lines are one of the most powerful tools of government, used to carve out space in maps, architecture, and politics. They serve as walls and connectors, defining relationships of have and have nots. While they are representative in concept, lines are used as worldbuilding tools, and have real consequences for those who suffer their violence.

Dilip da Cunha, a professor and landscape architect, explores the power of the line in his book, The Invention of Rivers. Landscapes we consider to be natural, he claims, are actually culturally constructed by the lines we use to describe them. The line allows nature’s ephemerality to be made static, freezing dynamic processes in time and space. Simplifying nature with linear separation between land and water allows the “wild” to be tamed for development right up to the water’s edge. Over time, development hardens these imagined lines in place, materializing mapped worlds in concrete and sand.

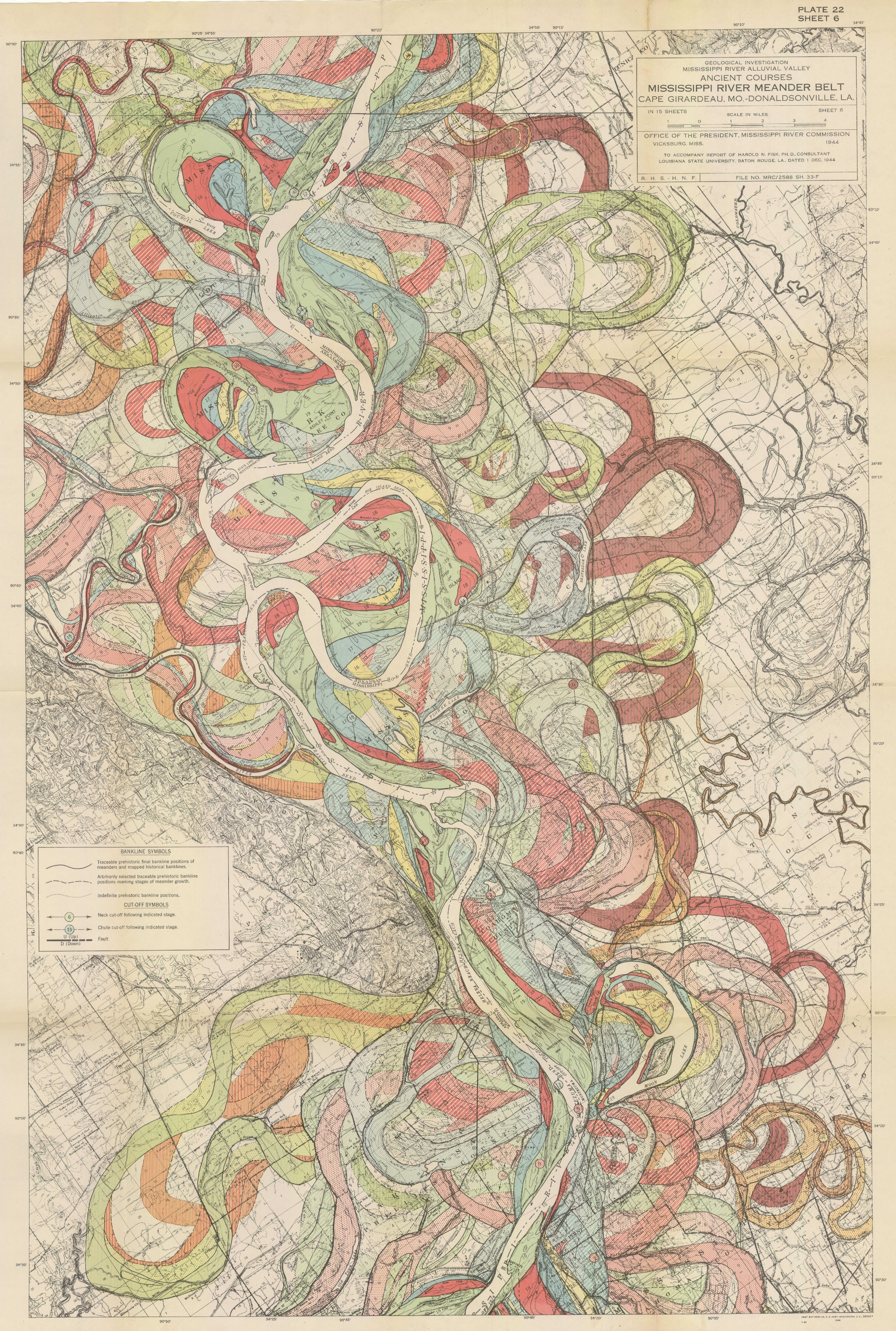

Geologic time, however, is unrelenting. Water is powerful, dynamic, and fluid. It does not obey terrestrial laws of physics. These lines easily dissolve as storm surges, cloudbursts, waves, and sea level rise demonstrate water’s verticality, reclaiming land through flooding and erosion. Harold Fisk’s famous Mississippi River maps diagram water’s power, constantly snaking through the landscape to carve new terrains. This diagram forces one to rethink the idea of the “waterfront;” by understanding historic water-land interfaces, we can begin to imagine the summed presence of water in a landscape, not just its momentary appearance.

The Lines of Jamaica Bay

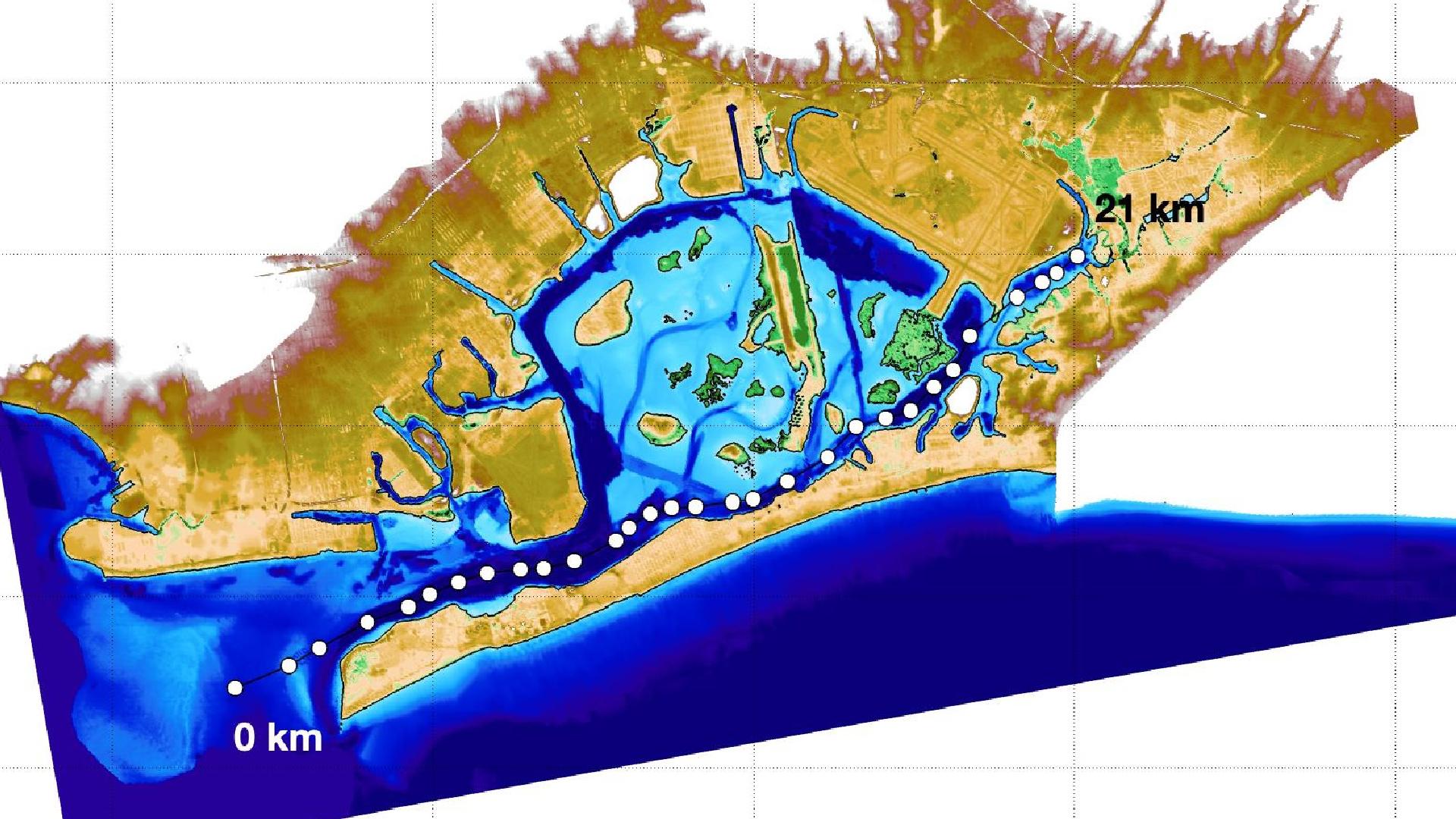

New York City’s Jamaica Bay is no stranger to this practice of line drawing. Maps from as early as 1651 have used lines to draw the waterfront of the American frontier to enable through navigation, resource extraction, and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. Later mapping efforts in the 1700s and 1800s sought to survey New York’s waterfront to identify safe shipping channels and opportunities for infill. These tools for spatial control, as shown in the GIF below, became increasingly detailed to enable imaginaries of a controlled waterfront. Dirt, trash, and discarded oyster shells became new weapons of invasion, filling in marshland to create new space for development once New York had grown too large for its confines.

These land reclamation projects, like JFK Airport’s runway construction in 1948, appeared useful at the time. Time has disagreed. Under a changing climate, rising sea levels and intensifying storms are flooding communities around Jamaica Bay. Areas of infill – over water and rivers – are the first to flood, restoring the city’s historical pre-development waterfront, if only for a moment. When floodwaters recede, land prevails. These spaces of overdevelopment ignore water’s summed presence upon the landscape, and yet modern policy and government blames water for encroaching on development, and not the other way around. Is flooding not a problem that we invented? We picked the wrong fight!

Our modern development in flood-prone areas inherently embodies a certain level of risk. Governments and developers have accepted that the profit from building in floodplains – given their proximity to urban centers – exceeds the financial risk posed by flooding. Yet, when these spaces flood, insurance and disaster relief programs bail out (pun intended) landowners to incentive redevelopment on historically flooded plots. Infrastructure in these wet landscapes fossilizes the most up-to-date science of ecology, hydrology, and economics to maximize profit given certain probabilistic thresholds of modeled flood events. We need an alternative understanding of the waterfront to reimagine our relationship with its edge – one that protects people and honors the sum of water’s presence.

Inviting Room for Movement

This project aims to melt these ice-cold accusations against water by first demonstrating the arbitrary nature of waterfront mapping. The violence of colonial lines defining water and land, access and extraction, and movement and target are pure constructions of perception. Each map represents the scientist’s series of decisions – a methodology – used to define representations of space. Before the invention of digital mapping tools, waterfront maps were generalized, often collapsing infinitely complex textured coastlines into smooth sweeping curves. Even after mapping technology modernized, coastlines still reflected the z-axis for which the scientist decided where water suddenly became land.

Waterfronts, however, are far more murky. The vertical movement of water – through tides, storm surges, waves, and sea level rise – challenges the singular z-axis datum for which water is drawn; water exists at all points between its highest and lowest historical extents. Hydrological science tries to remedy this through statistics by calculating tidal datums (from sea level to mean higher high and mean lower low water), sea level rise rates, flood event probabilities, and rainfall models. These estimates, however, serve to enable development in the floodplain by estimating the likelihood of water’s verticality posing a problem to infrastructure.

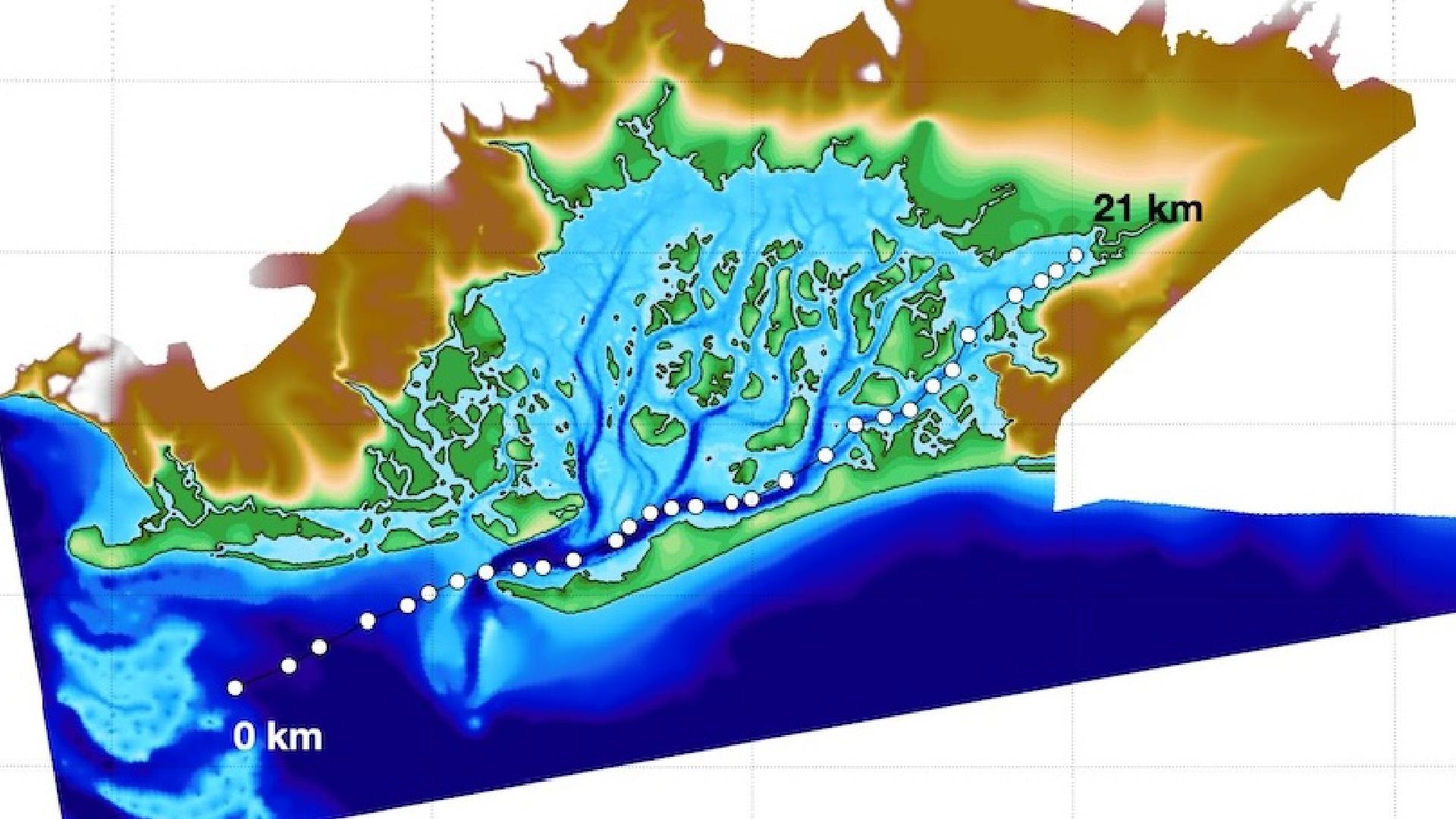

We propose the idea of the waterfront as an amorphous space in constant motion, where lines are an insufficient tool for delineation. Jamaica Bay provides a helpful case study to demonstrate the amorphous waterfront because of its varying edge typologies. JFK Airport’s infill is sited next to shrinking marshland, and expanding landfill, flood-prone development, dredged channels, and seawalls. The Bay’s history of government terraforming and dredging projects based on mapping surveys helps demonstrate how water, when subjected to the violence of the line, becomes doubly victimized during flood events by being trapped and a perpetrator of violence. Yet, as the elevation and historical maps below demonstrate, these projects are, themselves, the cause of flooding.

The modern waterfront of Jamaica Bay is no different than da Cunha’s invented rivers. Figure 3 shows NYC borough, NYS civil, federal coastline, OpenStreetMap coastline, and NYC MapPluto boundaries laid upon a hillshade terrain of Jamaica Bay. These lines all hold critically important legal roles in defining jurisdiction, infrastructure, and water boundaries. So why, then, are they not concurrent?

It is because water is messy. It is ambiguous, ephemeral, and in constant motion. By overextending waterfront boundaries, governments absorb water into the terrestrial sphere of control; by underextending, they minimize risk. On sunny days, this difference matters, but during storm events, these boundaries dissolve. Figure Y shows a hillshade map of Jamaica Bay with the Hurricane Sandy inundation zone, 2050 100-year floodplain sea level rise projection, and FEMA FIRM map.

The ambiguity of the waterfront is complicated by these real or projected flood events which suggest that not only do current lines fail to reach consensus on a “waterfront” – they ultimately fail to hold any relevance for water’s summed presence upon the landscape.

To address the flood risk of Jamaica Bay’s current development, New York City is turning to its historic colonial owner: the Dutch. 55 percent of the Netherlands sits in flood-prone areas, so in response, the Dutch government has implemented a series of hydro-engineered megaprojects and zoning codes to protect development. Massive levees, flood gates, and pumping systems keep water out, while floating or floodable architecture keeps people dry. This approach embraces living with water, blurring the lines of the waterfront. Communities across the tri-state area like Hoboken and Staten Island have adopted projects based on Dutch design principles.

We challenge this appropriation of Dutch engineering to protect the coastline of their former colony by asking: are there historical examples of living with water that already exist in New York? Rather than look to the same Western methodologies that enabled development to encroach on water, we look to Indigenous knowledge that is contextual to the landscape of Jamaica Bay. The Lenape (meaning “original peoples”) lived in Lenapehoking (the coastal areas comprising so called Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York) for time immemorial. Over centuries, their communities, language, and cultural practices evolved around water, constituting an ontological system that centers inter-relations between humans and more-than-humans. While the Dutch forced removal of the Lenape in 1609 erased much of this knowledge, fragments survive in language, stories, and archeology. We turn to these precious remnants to build a decolonial framework for conceptualizing the waterfront.

Rematriating the Waterfront through Lenape Epistemologies

The Lenape have made Lenapehoking their home for thousands of years. The area around Jamaica Bay was particularly kind, supporting multiple Lenape communities who fished, hunted, and traveled along its shores. Lenape communities located their structures, particularly in Canarsie, in the floodplain and near the water, using ancestral knowledge of flood risk to protect people and make the most of coastal landscapes. This knowledge of water was fundamental to the Lenape; the Lenape origin story tells of the land being born from a muskrat scooping mud from the seafloor and piling it on a turtle’s back. The land on which we all live, Lenapehoking, is referred to as “Turtle Island,” claiming that land is borne from water. This challenges Western notions of flooding by suggesting the shifting waterfront results from the vertical movement of land, while water stays static. It also positions land as an act of generosity from a living being – the turtle and the muskrat – capable of interrelations with people.

These active, intentional relationships between the Lenape and water are not transactional – they are generative and world building. The Lenape comprised multiple communities, referred to by their relationship with water: Unami (“people down the river”), Unalachtigo (“people by the ocean”), Nanticoke (“people of the tidewaters”), and Munsee (“people of the stony country”). Access to water served as a link between these communities. Dutch colonization of the coastline pushed the Lenape west, severing them from the water that connected them. Surviving communities hid in swamps like Jamaica Bay – areas where water’s dynamism made land unproductive for Western agricultural practices. Access to water, rather than separation from it, is key to Lenape worldviews, but hindered by modern waterfront development.

Lenape culture and practice view water as alive, and more-than-human. Robin Wall Kimmerer, an Indigenous scholar and scientist explores this principle in the context of a Bay: “A bay is a noun only if water is dead. When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb wiikegama – to be a bay – releases the water from bondage and lets it live.” Part of living is movement, horizontally through currents, and vertically through flooding and tides. Containing, filling in, or dredging based off of lines thus becomes literal violence against water’s right to move freely. Language becomes a metaphorical line, too, enacting violence against water through conceptual containment inherent in definitions like “tidal datum,” and “100-year flood.” Along the shores of Jamaica Bay, concrete embankments and scientific projections become carceral, trapping waters who are meant to ebb and flow. Denying this movement, however, fails to deny the inevitable: flooding.

Surviving Lenape languages keep this movement alive, inviting the receding and flooding of the water. Language, as a living archive, contains records of worldviews, traditions, and culture. Lenape nouns, especially, suggest a living conceptualization of more-than-humans like water, using animate pronouns, “he,” “she,” or “they” to refer to what, in English, would otherwise be inanimate. Verbs thus become social, connecting two beings through interrelations. To demonstrate this – rather than providing a literary dictionary – we offer a video (at the top of this post) of Jamaica Bay overlaid with Lenape language to connect Lenape ontologies with place, suggesting new relationships that honor water’s personhood.

Reframing Jamaica Bay’s Waterfront

Through these Lenape ontologies and epistemologies, we can reimagine Jamaica Bay’s map not through lines and delineations, but through language and interrelationships. Rather than separate land and water with a binary waterfront, this new worldview connects the upland to the bay through water and its movement. The violence of lines of separation gives way to embodied practices of connection. In describing the waterfront as space, and not a boundary, we invite room for water’s verticality, flow, and dynamism. Most importantly, we do this through Lenape histories borne from Lenapehoking, not design principles imposed by the Dutch.

Communities around Jamaica Bay have already suffered at the hands of the violence of the line. JFK Airport and communities like Edgemere and Canarsie, built on marsh infill, face increasingly frequent flood events as seas rise and storm events become more frequent. Meanwhile, the double violence of the line both contains (kills) and problematizes water. Water, however, is not the problem. Lenape stories position water as a giver of life – a generous provider on which the world is built. From this perspective, we understand our Western practices – of controlling, containing, and quantifying water – as the true challenge to overcome. The waterfront is not a binary. It is alive.

References

Datasets

Historical Maps

- J.B. Beers & Co. New map of Kings and Queens counties, New York: from actual surveys. New York: Published by J.B. Beers & Co., . ©, 1886. Map. Link.

- Manuscript map of British and American troop positions in the New York City region at the time of the Battle of Long Island Aug.-Sept. [?, 1776] Map. Link.

- New York; [1809], Map Collection, NYC-[18-?]a.Fl; Brooklyn Historical Society. Map. Link. -NOAA Office of Coast Survey. JAMAICA BAY AND ROCKAWAY POINT. [1903] Map. Link.

- Plan of New York and Staten Islands with part of Long Island, survey’d in the years , & 82. [1782] Map. Link.

- Survey of the Coast of the United States. New York Bay and Harbor and the Environs. [1845] Map. Link.

- Visscher, Nicolaes. Novi Belgii Novaeque Angliae: nec non partis Virginiae tabula multis in locis emendata. [Amsterdam?, 1690] Map. Link.

Legal Waterfront

- NYC Planning. Borough Boundaries (Clipped to Shoreline). [2025] Shapefile. Link.

- NYC Planning. MapPLUTO. [2025] Shapefile. Link.

- NYS GIS Clearinghouse. Civil Boundaries. [Nov., 2024] Shapefile. Link.

- OpenStreetMap. Coastline. [2024] Shapefile. Link.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Tiger/Line Federal US Census Coastline. [2024] Shapefile. Link.

Scientific Waterfront

- FEMA. FIRM Maps. [2025] Map. Link.

- Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. February 19, 2024. Sea Level Rise Maps (2050s 100-year Floodplain). Accessed March 6, 2025. Link.

- New York Department of Small Business Services. Feb 19, 2024. Sandy Inundation Zone. Accessed March 6, 2025. Link.

Lenape Language

- Delaware Tribe of Indians.. n.d. Lenape Talking Dictionary. Accessed March 6, 2025. Link.

Literature and Precedent

- da Cunha, Dilip. 2019. The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hall, Karelle. “Eeskw Nutapimun: Nanticoke and Lenape Fluid Sovereignties.” Order No. 31767838, Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies, 2025. Link.

- Kimmerer, R.W. (2017), “Learning the Grammar of Animacy.” Anthropol Conscious, 28: 128-134. Link.

- McCulloch, Joe Baker, and Gabrielle Hughes, eds. 2023. Lenapehoking: An Anthology. New York: Brooklyn Public Library.

- Pareja-Roman, L. F., Orton, P. M., & Talke, S. A. (2023). Effect of estuary urbanization on tidal dynamics and high tide flooding in a coastal lagoon. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 128, e2022JC018777. Link.