Nuclear Ecology: Data Voids of Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station

The project explores the impact of Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station on ecosystems – both natural and political – in Southern Florida. Tracing how nuclear infrastructure creates an artificial landscape, our project reveals a key tension: while Turkey Point’s cooling canals have been long under scrutiny by environmental groups due to their proven leaking of salt water into local aquifers, this warm brackish water has surprisingly created an ideal habitat for American crocodiles. Set against a backdrop of concerns for the risk associated with nuclear generation, our research aims to bring to light the various data voids – or missing information – connected to Turkey Point. Amidst a contentious political landscape with scandals connected to Florida Power & Light, the owner of the plant, the project focuses on mapping available information and the array of actors, from Senators to crocodiles, to point to gaps in Turkey Point’s narrative. The research aims to expose a series of complex relationships between ecology and political motivations and, ultimately, contribute a nuanced perspective to discourse on impact of nuclear infrastructure.

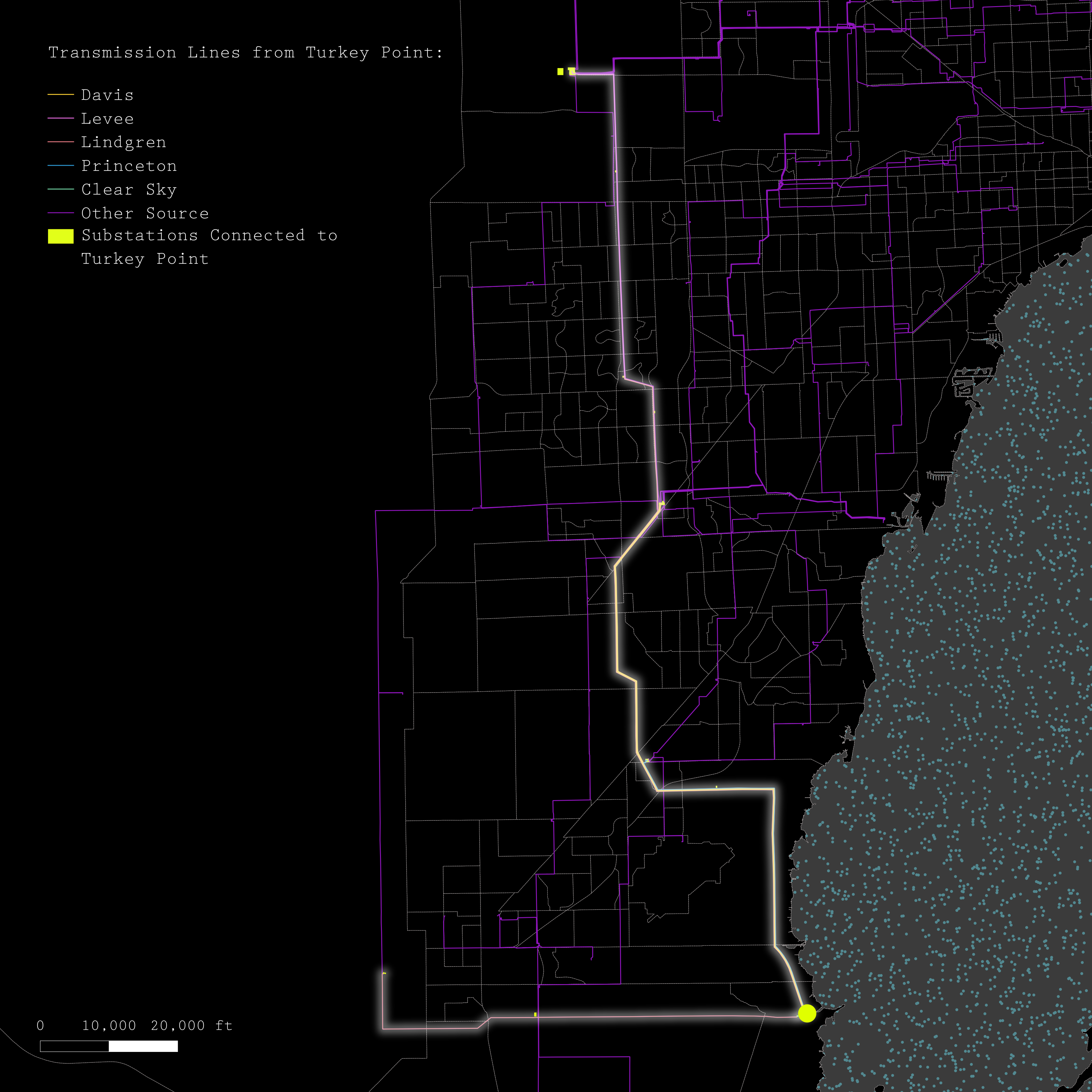

Transmission lines originating at Turkey Point.

Transmission lines originating at Turkey Point.

Context

Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station was completed in 1972 to meet the energy demands of South Florida’s booming population, under the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson. Located twenty five miles south of Miami, the plant sits in a sensitive ecosystem between the Everglades National Park and Biscayne Bay. It sits directly on top of the Biscayne Aquifer, the primary public water supply for Miami-Dade and Florida Keys.1 The plant is owned by Florida Power & Light Co (FPL), and comprises seven units: units 1, 2 and 5 are oil/gas, whilst units 3 and 4 are nuclear generating.2 With units 6 and 7 in construction, our investigation focuses specifically on units 3 and 4. The Turkey Point cooling canals span 168 linear miles, an area so large that it can be seen from space or zoom level 1, and stands as the only plant in the US that uses earthen cooling canals in its operations.3 After a contentious exchange involving multiple lawsuits between FPL and environmental groups, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved and reinstates Turkey Point’s license extensions in March 2024, allowing Units 3 and 4 to operate until 2052 and 2053 respectively.

Hatchlings of American Crocodiles at Turkey Point Nuclear Power Plant. Image courtesy NRCgov, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Hatchlings of American Crocodiles at Turkey Point Nuclear Power Plant. Image courtesy NRCgov, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

American Crocodiles at Turkey Point

Turkey Point has since become a thriving sanctuary for American crocodiles, a species once on the brink of extinction. South Florida’s crocodile population was estimated to have numbered over 3000 in the early 1960s, but their population had dwindled to just 150-300 by the mid-1970s and were classified as an endangered species. Reasons for the historical decline of its population in North America include habitat loss, road kills, hunting for the hide industry, pet trade, and wildlife exhibitions.4 The construction of Turkey Point’s cooling canals had inadvertently created a near-perfect habitat for these crocodiles. These canals serve an essential engineering purpose: as water cycles through the nuclear plant, it removes excess heat before cooling down in the canals and re-entering the system. The canals have provided abundant prey and elevated berms for nesting – but, most crucially, the absence of human interference. By 2007, the American Crocodile Distinct Population Segment in Florida was reclassified from Endangered to Threatened.5

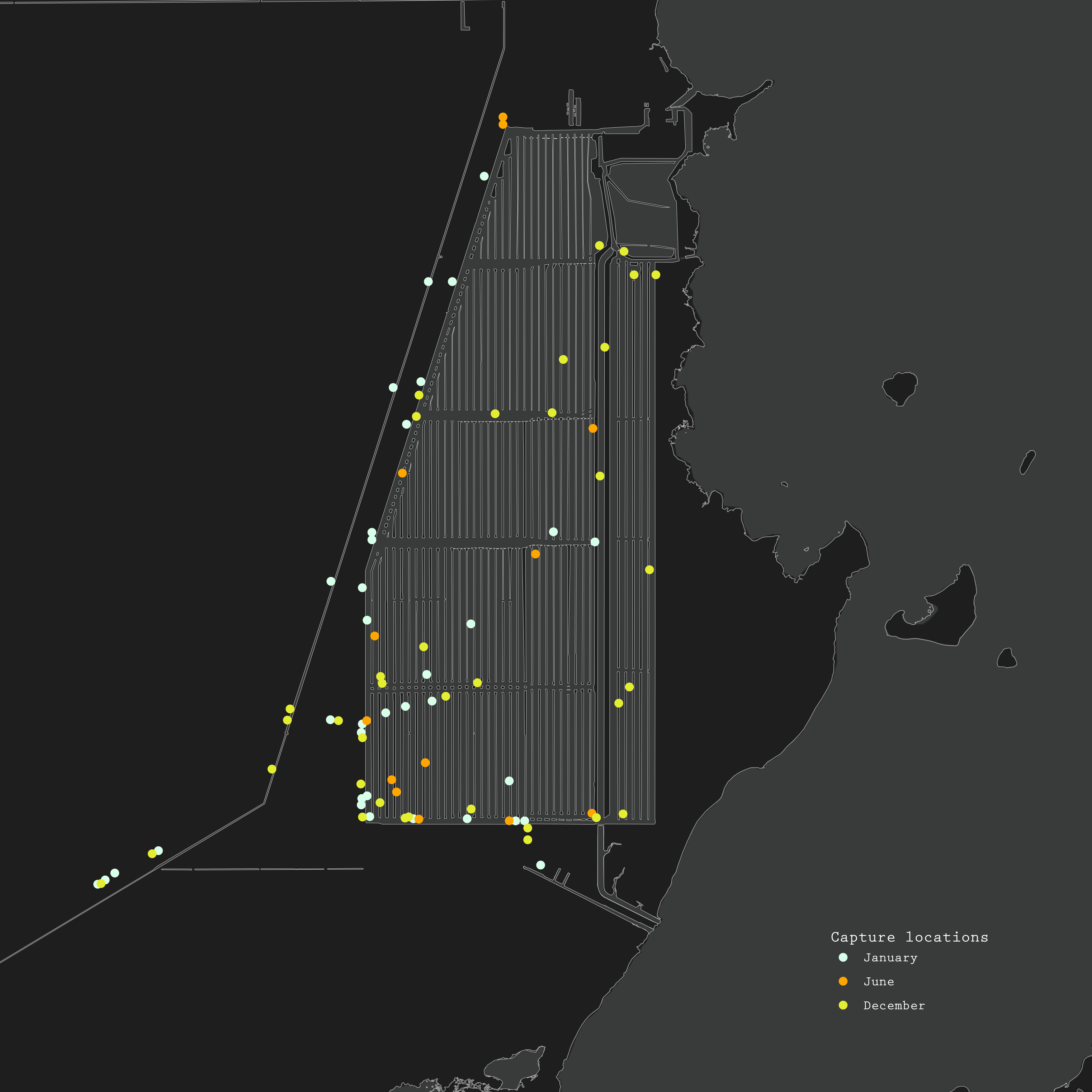

American crocodile capture locations at Turkey Point Power Plant from the 2012 January, April and November capture events.

American crocodile capture locations at Turkey Point Power Plant from the 2012 January, April and November capture events.

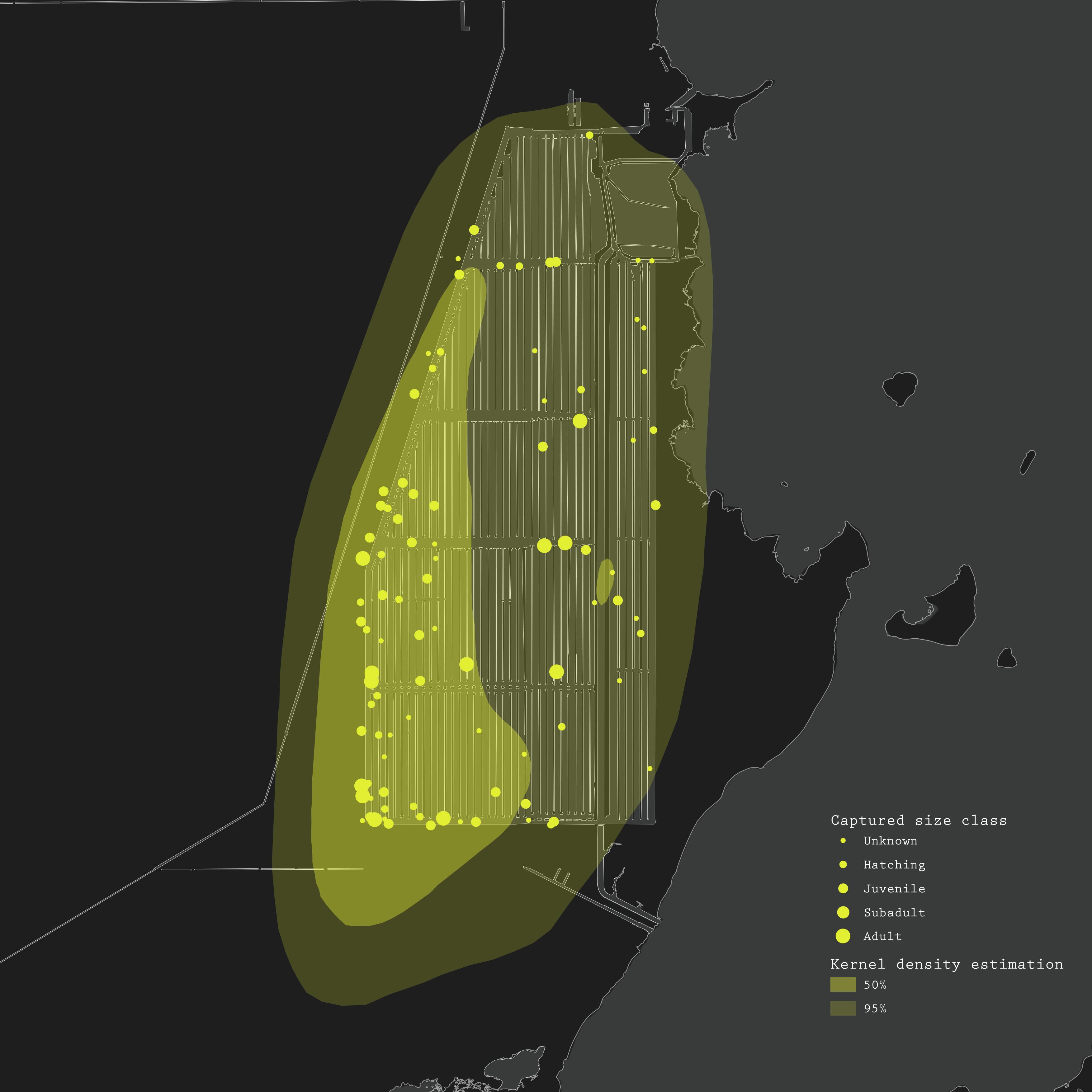

Kernel Density Map of crocodile locations at Turkey Point Power Plant during August 2012 spotlight survey.

Kernel Density Map of crocodile locations at Turkey Point Power Plant during August 2012 spotlight survey.

Our research compared user generated sightings from iNaturalist with FPL published data on crocodile monitoring. Given the fact Turkey Point facility is a highly restricted zone, it is unsurprising that user generated sightings were far fewer than that of the plant’s owner. However, while user generated sightings gradually proliferated, FPL stopped publishing data in 2012. Adding to this, we found that clicking any links posted on their official crocodile monitoring website page resulted in a “page not found” error. Broken links and old data both present a data void; an absence of information that appears to be more of a PR stunt than a commitment to transparency and real-time ecological monitoring.

American crocodile crowd source data from iNaturalist.

American crocodile crowd source data from iNaturalist.

Land surface temperature from 2013 to 2025 showing the relatively high temperature in cooling canels.

Land surface temperature from 2013 to 2025 showing the relatively high temperature in cooling canels.

Water Quality Testing

The canals have long been suspected to have had serious problems, and in recent years, it has been confirmed that they are leaking salt water and contaminating the Biscayne Aquifer.6 2012 marked a significant turning point: the very same year FPL stopped publishing crocodile monitoring data, they responded to pressure from environmental groups and addressed saltwater intrusion. In conducting an internal investigation, FPL published a plan to add water from the Floridan Aquifer to freshen the canals and dilute their saline content.7 The public acknowledgement of a longstanding issue prompted further investigation from both environmental groups and county legislators. One such example was a study published in the Miami Herald conducted by Miami-Dade County which reported tritium levels in Biscayne Bay up to 215 times higher than normal ocean water.8 Tritium is a radioactive isotope that is used for water tracingand, although these levels are still far below what the Clean Water Act accepts in drinking water, the presence of tritium led scientists to believe that water was leaking, and travelling with ammonia and phosphorus, into the bay.9

Water systems in Southern Miami-Dade County including canals, streams, and lakes close to Turkey Point.

Water systems in Southern Miami-Dade County including canals, streams, and lakes close to Turkey Point.

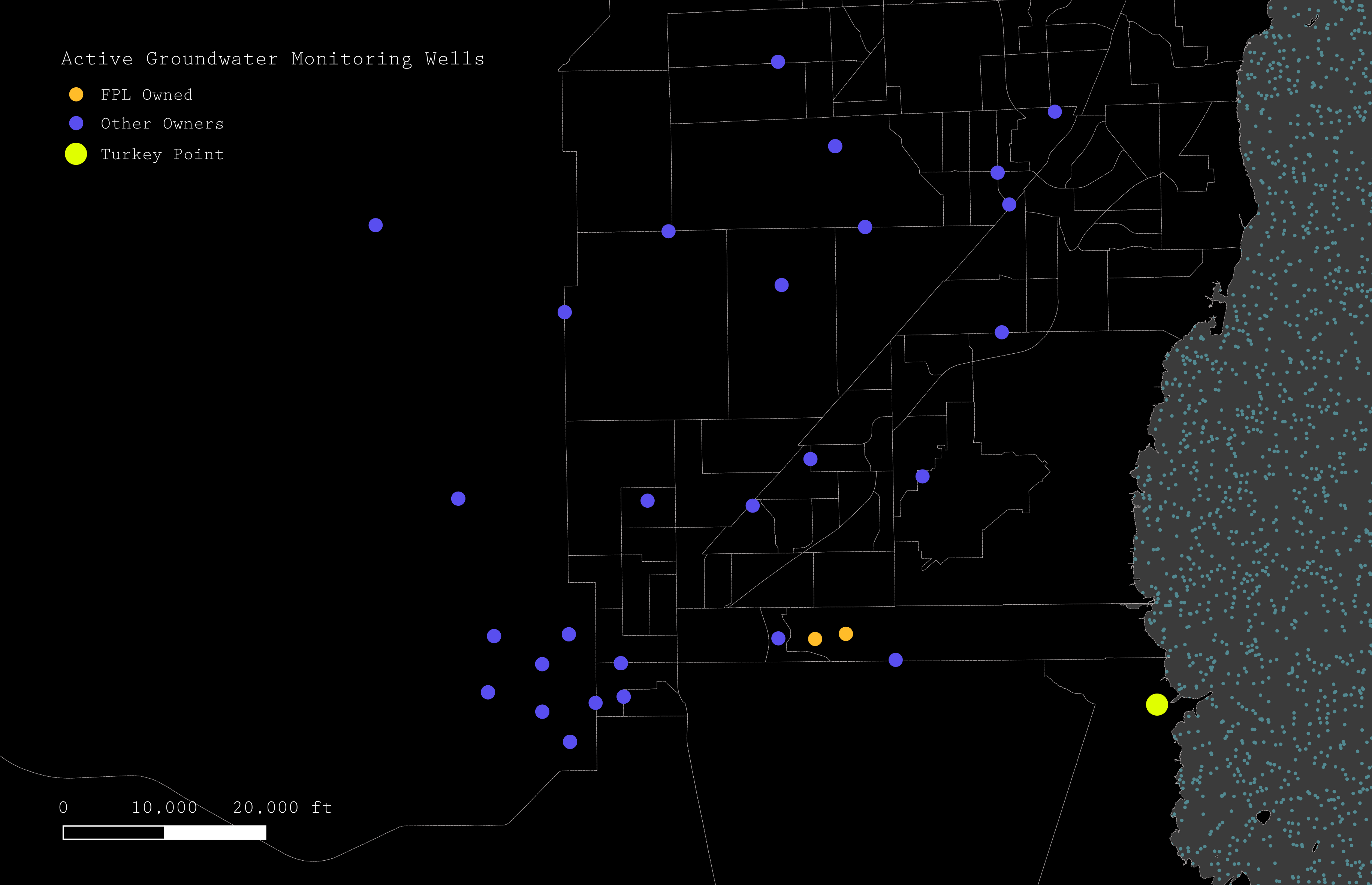

Active Ground Water Monitoring Wells near Turkey Point, highlighting FPL owned wells.

Active Ground Water Monitoring Wells near Turkey Point, highlighting FPL owned wells.

Mapping water quality data focused on ammonium, salinity, nitrogen oxide and phosphorus revealed a higher concentration of each both directly around Turkey Point and further north in the bay in 2024, than the concentrations in 1980.10 The concentrations north of the plant can be attributed to prevailing currents from the Atlantic which bring particulate matter north past Miami. Our research, however, revealed a significant data void in the types of chemicals being tested in the area. In 441 chemicals tested across water monitoring stations, there was not a single nuclear isotope. Of the groundwater monitoring wells, two of the closest to Turkey Point are owned by FPL – presenting a questionable conflict of interest.

Census Tract changes in Southern Miami-Dade County from 1960 to 2020.

Census Tract changes in Southern Miami-Dade County from 1960 to 2020.

Licensing & Census Tract Changes

In 2018, FLP became the first nuclear operator to seek to extend its operating license to a total of 80 years, which was met with backlash from environmental activists. In 2019, the NRC granted license extensions without a comprehensive environmental impact assessment, leading to a lawsuit enacted by Miami Waterkeeper, Friends of the Earth, Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). In 2022, the NRC reversed its prior decision and mandated a full environmental review, and by 2024 – after publishing the “Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement” – the NRC reinstated the license extensions, allowing Units 3 and 4 to operate until 2052 and 2053.11

An analysis of Florida’s census tract changes from 1960 to 2020 revealed an intriguing insight: while most tracts subdivided and increased as a clear result of urban development around Miami, Turkey Point was uniquely assigned its own census tract in 2020. The map shows that the line was deliberately drawn to enclose the facility. Notably, this tract is clearly not connected to any urban development, which raises questions about the reasoning behind the decision and its implications.

FPL used outdated census data from 1990 in their license renewal application published in 2018.12 The report cited continuity from its renewal filing in 2000 and for consistency in available environmental data, yet a lower population count clearly works in their favour to and gives a regulatory advantage to reduce perceived public risk and opposition. FPL’s interest in census outcomes is evident, though the political and regulatory implications are complex. While we presume that NRC incorporated updated census data in their assessment in 2022, the report does not make this entirely clear.13 Although there is no direct evidence, the appearance of a newly drawn tract around Turkey Point in 2020 raises speculation as to whether FPL had any influence in the redistricting process – potentially to position the facility as an isolated entity, with lower population in the vicinity, which would offer significant regulatory and strategic advantages.

Political Funding

The CEO of FPL Eric Silagy was implicated in an election manipulation scheme against Democratic Senator Jose Javier Rodriguez in 2020.14 Silagy was proven to have contributed “dark money” as a bride towards a ghost-candidate with the same last name as Rodriguez to create confusion and split the vote. The strategy proved effective as the Republican senator Ileana Garcia narrowly defeated Senator Rodriguez in District 37. Frank Artiles, a disgraced previous Senator and avid supporter of Turkey Point, was arrested for facilitating election manipulation and orchestrating the scheme itself.

Following the 2020 census, increased population figures contributed to the redrawing of district lines in Southern Florida ahead of the 2022 elections. These new boundaries fragmented the voting power of residents near Turkey Point – two-thirds of whom are Hispanic living in Miami-Dade county – diminishing the influence of Democratic leaning voters who support pro-regulation and pro-solar initiatives, spearheaded by Senator Rodriguez, which would break apart FPL’s energy monopoly of the area. Rodriguez again narrowly lost in a newly drawn District 37 to their Republican counterpart. A year later, Governor Ron DeSantis accused of racialized gerrymandering in congressional redistricting splitting up Hispanic communities, where the newly drawn 28th congressional district in which Turkey Point lies was cited as a critical example.

There is substantial evidence to suggest that FPL is not merely pursuing regulatory approval, but actively engaging in strategies to critically influence and act within their own political interest. Census track changes trigger redistricting processes and, in turn, can lead to politically advantageous gerrymandering. Whether the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is complicit in, or simply inattentive to, these dynamics remains a critical and open question.

Turkey Point lies at the intersection of energy infrastructure, ecological growth and political influence. While its cooling canals have inadvertently created an ideal environment for a once-endangered species, their leakage has contributed to the degradation of Miami-Dade and Florida Keys’ drinking water systems. Our research reveals how data voids, outdated metrics and political entanglements have shaped public narratives and regulatory decisions surrounding the plant. The Generation Station can be seen as a microcosm over a broader struggle over transparency from private infrastructure corporations and the manipulation of civic data for governance. As the plant is now set to move into operating in the 2050s, with the risk of hurricanes becoming ever more present, the stakes – ecological, political and social – only grow more urgent.

Citations

- Richard Luscombe, “Ageing nuclear plant in Florida at risk from climate crisis”, The Guardian, March 1, 2025

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Unit 3 | NRC.gov Florida Power and Light Co, Turkey Point Fact sheet

- LeBuff, C. (2016). Historical Review of American crocodiles along the Florida Gulf Coast

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. “Reclassification of the American Crocodile Distinct Population Segment in Florida from Endangered to Threatened; Final Rule.: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.” FWS.Gov, 20 Mar. 2007, www.fws.gov/species-publication-action/reclassification-american-crocodile-distinct-population-segment-florida.

- The Natural Resources Defense Council. Friends of the Earth et al. v. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 6 Aug. 2024, www.nrdc.org/court-battles/friends-earth-et-v-nuclear-regulatory-commission.

- Ecology and environment, inc. “FPL Turkey Point Initial Ecologic Condition and Characterization Report - June 2012.” Sfwmd.Gov, June 2012, https://www.sfwmd.gov/document/fpl-turkey-point-initial-ecologic-condition-and-characterization-report-june-2012

- Staletovich, Jenny. FPL Nuclear Plant Canals Leaking into Biscayne Bay, Study Confirms, 7 Mar. 2016, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/environment/article64667452.html

- Roelant, David. “Tritium Levels No Threat to Our Drinking Water, by Dr. David Roelant.” Florida International University’s Applied Research Center, 17 Apr. 2016, Tritium levels no threat to our drinking water, by Dr. David Roelant The data mapped was sourced from Miami Dade Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources, Division of Environmental Resources Management (DERM)

- The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Turkey Point Nuclear Plant, Units 3 & 4 – Subsequent License Renewal Application.” NRC Web, 15 Oct. 2024, https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/operating/licensing/renewal/applications/turkey-point-subsequent.html

- Florida Power & Light Company. “Turkey Point Nuclear Plant, Units 3 & 4 – Initial License Renewal Application.” NRC Web, https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/operating/licensing/renewal/applications/turkey-point/er.pdf

- The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Turkey Point Nuclear Plant, Units 3 & 4 – Subsequent License Renewal Application.” NRC Web, 15 Oct. 2024, https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/operating/licensing/renewal/applications/turkey-point-subsequent.html

- Ariza, Mario, and David Folkenflik. “Florida Power CEO Implicated in Scandals Abruptly Steps Down.” NPR, NPR, 25 Jan. 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/01/25/1151453870/fpl-florida-power-ceo-eric-silagy

Data Source

- Earth Explorer, Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS Collection 2 level-1, https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ American Crocodile Monitoring Program Turkey Point, American crocodile capture locations at Turkey Point Power Plant from the 2012 January, April and November capture events. 2012, https://www.fpl.com/environment/wildlife/crocodiles.html

- American Crocodile Monitoring Program Turkey Point, Kernel Density Map of crocodile locations at Turkey Point Power Plant during August 2012 spotlight survey. 2012, https://www.fpl.com/environment/wildlife/crocodiles.html

- Species Sighting, iNaturalist, https://www.inaturalist.org/home

- Water quality, Miami Dade Department of Regulatory and Economic Resources, Division of Environmental Resources Management (DERM), 1980-2024

- Miami-Dade County Census 1962-2022, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets.html