The Line That Changed a Nation

INTRODUCTION

Nicosia, Cyprus is the world’s last divided capital city. The decades-long stalemate between Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriots over the UN-controlled Green Line—also known as the Buffer Zone, Neutral Zone, Dead Zone, and No Man’s Land—has resulted in politically and socially charged mappings of the island. A simple search for “map of Cyprus” yields dozens of interpretations of ethnic and geopolitical divisions at the scale of the country, with additional nuances coming to light at the scale of the Green Line. This project provides a brief overview of the events that led to the drawing of the Green Line, the perspectives from which the country and the Green Line are mapped, and the implications of these cartographic representations.

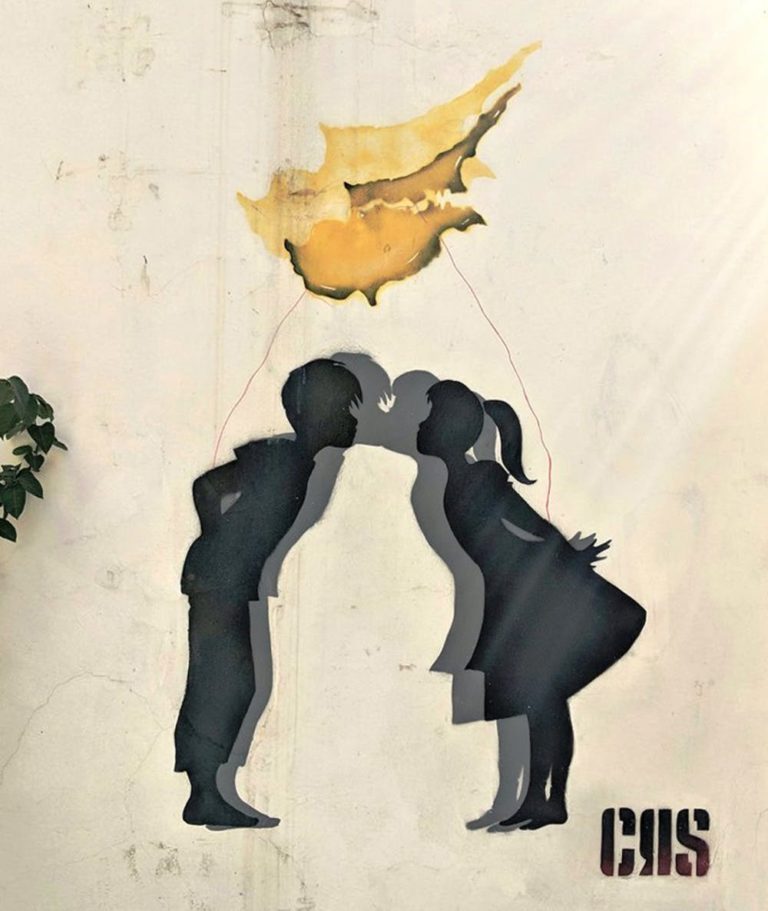

Unity in Peace. Street art in Cyprus depicting repercussions of the country’s divide. Source: Neos Kosmos.

BACKGROUND

The events that led to the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus are complex, span decades of conflict, and involve atrocities and conflict spurred both by Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots. The scope of this project focuses on the spatial and representational consequences of the events of the summer of 1974.

The Island of Cyprus

Cyprus is a small island in the Mediterranean Sea located south of Turkey and west of Syria that is home to both Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots; ethnically, however, Greek-Cypriots compose the majority of the population. Before the war the two ethnic groups both lived throughout the island, although Turkish-Cypriots tended to live among other Turkish-Cypriots in smaller communities. Post-conflict, the island was split into the Turkish north and the Greek south.

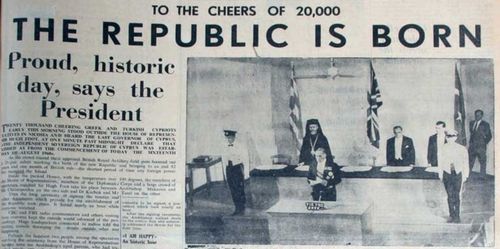

Independence and a Brief Period of Peace

The nuances of Cyprus’s history and political control by the Ottoman Empire, Greece, and England go beyond the scope of this project—for the sake of brevity and to maintain focus on the aftermath of the invasion, this historical summary begins in 1960 when Cyprus became an independent republic, free of British rule (although two large British bases remain on the island to this day). Cyprus’s new constitution allocated separate control to Greek- and Turkish-Cypriot municipalities in an attempt to satisfy both communities and prevent conflict; however, just four years later, these concessions proved unsuccessful.

Celebration of Cypriot Independence. Source: Military Histories: The Green Line in Cyprus.

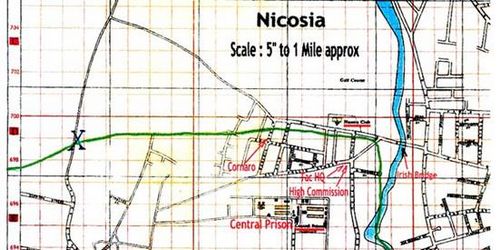

Drawing the Green Line

By 1964, armed conflict between Greeks and Turks rose to a level of alarm that required UN intervention: sending peacekeeping forces to the island (to this day, the UN remains in Cyprus in one of its longest-ever peacekeeping missions). Despite efforts by the UN to control the fighting, tensions continued to rise and the Cypriot military eventually accepted intervention by the British as well. Their troops took control and oversight of local Cypriot and Turkish military units,and British Major General Young embarked on a set of discussions and concessions with Greek and Turkish National Contingents. Attempting to appease both sides, he began drawing a line on one of his maps of Cyprus to separate the Greek south from the Turkish north. General Young’s selection of a green pencil was no random choice—blue and red were out of the question given that they were associated both with the British flag (the former enemy) and with the Greek and Turkish flags. Green, he argued, was associated with military fortifications and was the most ‘neutral’ color choice. General Young went back and forth with Greek and Turkish representatives, erasing and re-drawing the line until both sides were in agreement. And just like that, the Green Line was born, and a country divided. Although the Green Line was meant to be a temporary step to restore peace between the two sides, it became a permanent and impassable part of the island after the Turkish Invasion of 1974.

The original Green Line is drawn. Source: Military Histories: The Green Line in Cyprus.

The Invasion of 1974

Continued violence between the two sides followed the events of 1964 and persisted up until 1974 when the conflict came to a boiling point. Greek nationalists attempted a military coup, which Turkey took as a threat and subsequently sent forces to invade the island in what they called a “peacekeeping mission.” Turkey took control of the northern half of the island, and all Greek-Cypriots living in the north were immediately forced from their homes, and Turkish-Cypriots in the south were relocated to the north. To this day, no country (nor the UN) other than Turkey recognizes the so-called ‘Northern Republic of Cyprus.’

Turkish forces storm the streets during the 1974 invasion. Source: T-Vine.

The Aftermath

Over 200,000 Cypriots were displaced from their own homes and became refugees in their own country overnight. The division of the capital city of Nicosia creates a painful and delicate tension in which some Greek-Cypriots have lived less than a mile from their old homes and memories, yet are remain refugees. It wasn’t until 2003 that border crossings opened between the two sides. Even after the crossings opened, many decided not to go to the Turkish side either in protest or due to the emotional trauma they endured. To this day, in order to cross to the Turkish side, Greek-Cypriots are required to show their passport at crossing points.

Greek Cypriots cry over the loss of their homes. Source: Neos Kosmos.

INSIDE THE GREEN LINE: THEN AND NOW

The drawing of the Green Line not only affected the forced migration of Cypriots on either side of the line, but it also deeply affected the nation’s symbols of culture within the Green Line that were ‘neutralized’ due to their location within the Buffer Zone. Furthermore, the way in which the Green Line is drawn in maps today—usually greyed out—underscores the implication that artifacts of culture within the Buffer Zone are disregarded and ‘neutralized’ themselves. This section calls out two of the most pertinent examples of ‘neutralized’ culture.

The Nicosia International Airport

First is Nicosia’s airport: it was set to become a travel hub for the Mediterranean and the Middle East, bringing in tourists from around the world and exhibiting all that Cyprus has to offer. Now, it sits abandoned and in disrepair—untouched since it was deserted in 1974.

The Nicosia International Airport Then. Source: World Abandoned.

The Nicosia International Airport Now. Source: Dimitris Sideridis.

The Nicosia International Airport Now. Source: Dimitris Sideridis.

Ledra Palace Hotel

Second is Ledra Palace: once one of Nicosia’s most upscale hotels that was home to celebrations for upper-class Cypriots and a symbol of the city and country’s prosperity starting from its opening in 1949. After the first conflicts broke out in 1964, the UN’s peacekeeping forces have set up shop within the once-glitzy hotel walls, and its common areas converted to spaces for peacekeeping talks between Greek and Turkish politicians. As of 2004, it also became the site of an official crossing point between the north and the south.

Ledra Palace Hotel Then. Source: ARTos Foundation/MAPS.

Ledra Palace Hotel during the invasion 1974. Source: Dimitris Sideridis.

Ledra Palace Hotel as UN Peacekeeping Forces HQ Now. Source: AP News.

MAPPING PERSPECTIVES

The below maps by the author underscore spatial and political representations of Cyprus at the country- and city-scale. These maps are interpretations and re-creations of how various parties have chosen to represent Cyprus and the Green Line based on their political views. Each map becomes a form of counter cartography, political power play, or a social construct.

A careful selection of the ‘fill’ of the Green Line in these maps as Lefkara lace—recognized by UNESCO as part of the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity—is made to highlight the persistence of Cypriot culture and the strength of its people despite the unimaginable suffering they have endured. Using this pattern for the Green Line fill allows for the utilization of a typical architectural representation strategy, but instead of employing an ambiguous pattern or objective material as a fill, the use of Lefkara lace transforms the map into a form of counter cartography, making visible the author’s own views.

Cypriot Perspective: Country Scale

Cyprus as a unified nation. The island represented as it is on the Cypriot flag: unified. It is important to note that the majority of Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriots, and especially the younger generations, desire a unified Cyprus; thus, the ‘Cypriot’ perspective often becomes the Cypriot + Turkish non-politician view.

Turkish (Politician) Perspective: Country Scale

Northern Cyprus as center stage. Maps like this follow the representational strategy employed by political and tourist organizations from the Turkish north side. In these maps, the southern Greek side of the island is greyed out and discounted, represented as an inactive and irrelevant player in their eyes. Again, this perspective is held mainly by politicans, not necessarily by most Turkish-Cypriot individuals.

British Perspective: Country Scale

British-made Cyprus. This map depicts all territories created by the British, yet represented in ways that counter the traditional narrative. British bases are depicted in the ‘neutral’ language of being greyed out, indicating that they should not be active players given that Cypriots declared independence from them over 60 years ago. In addition, although the British drew the Green Line, it is still represented with the Lefkara lace fill, indicating resilience of Cypriots and their right to own the land that should be theirs.

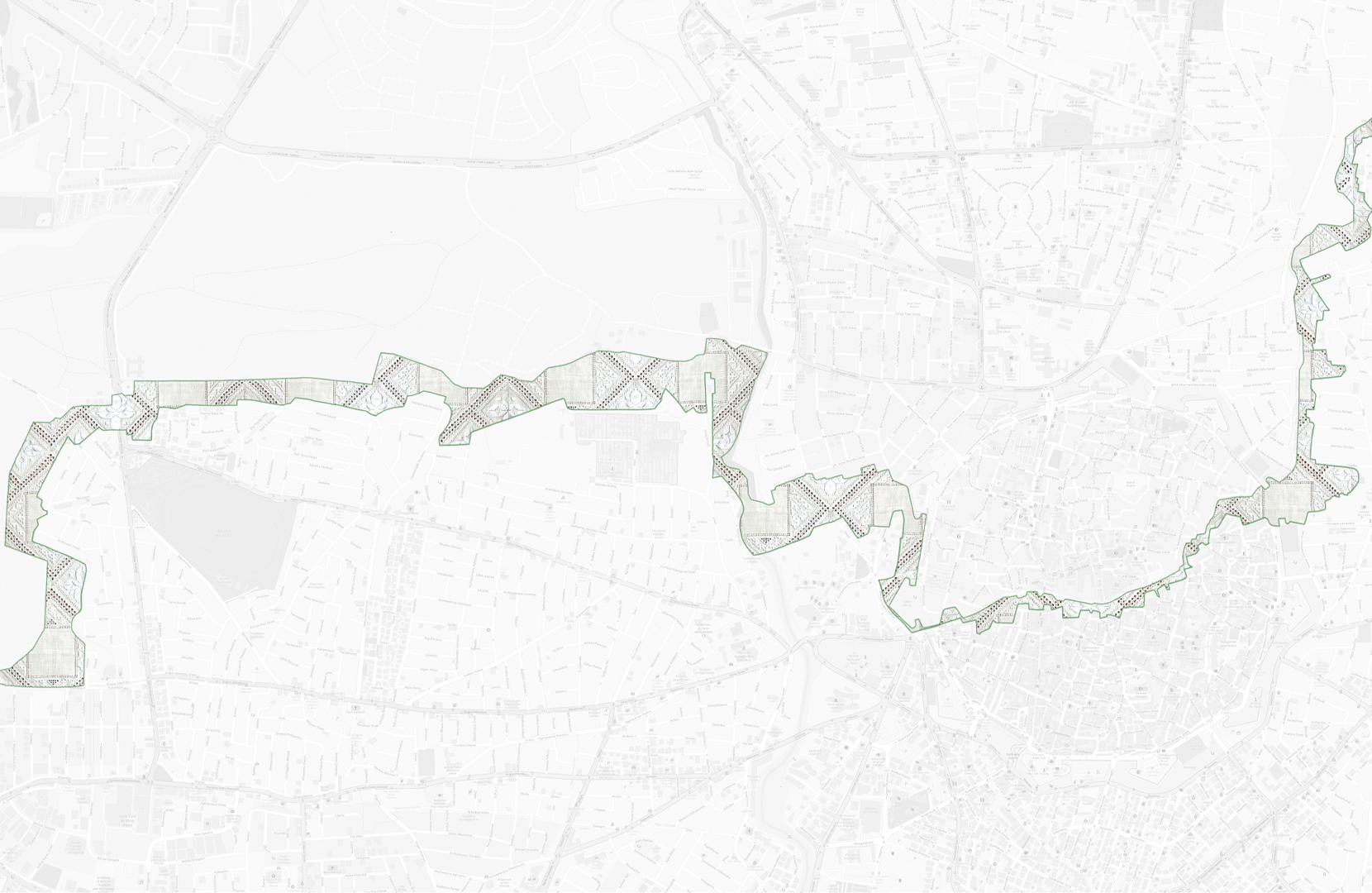

Green Line + Buffer Zone: Pre-2003

Closed, divided, unreachable. While these words aptly describe the nature of the Green Line for nearly 30 years, the representation of the Green Line itself attempts to counter that.

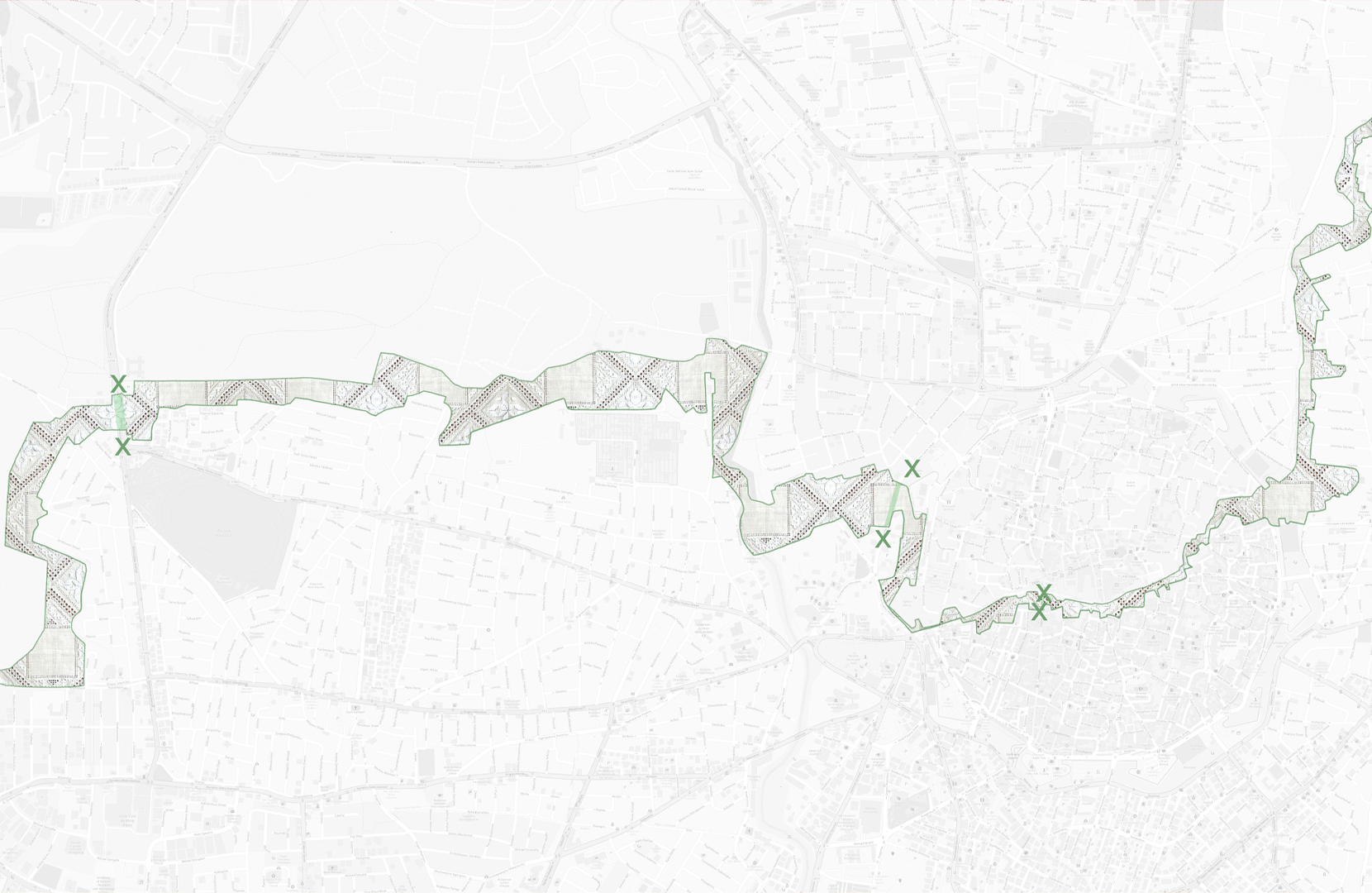

Green Line + Buffer Zone: Post-2003

Opened yet restricted. Official crossing checkpoints opened the divide between north and south. Yet, while these openings within the Green Line allowed for physical crossing, many Greek-Cypriots chose not to cross because of the emotional toll.

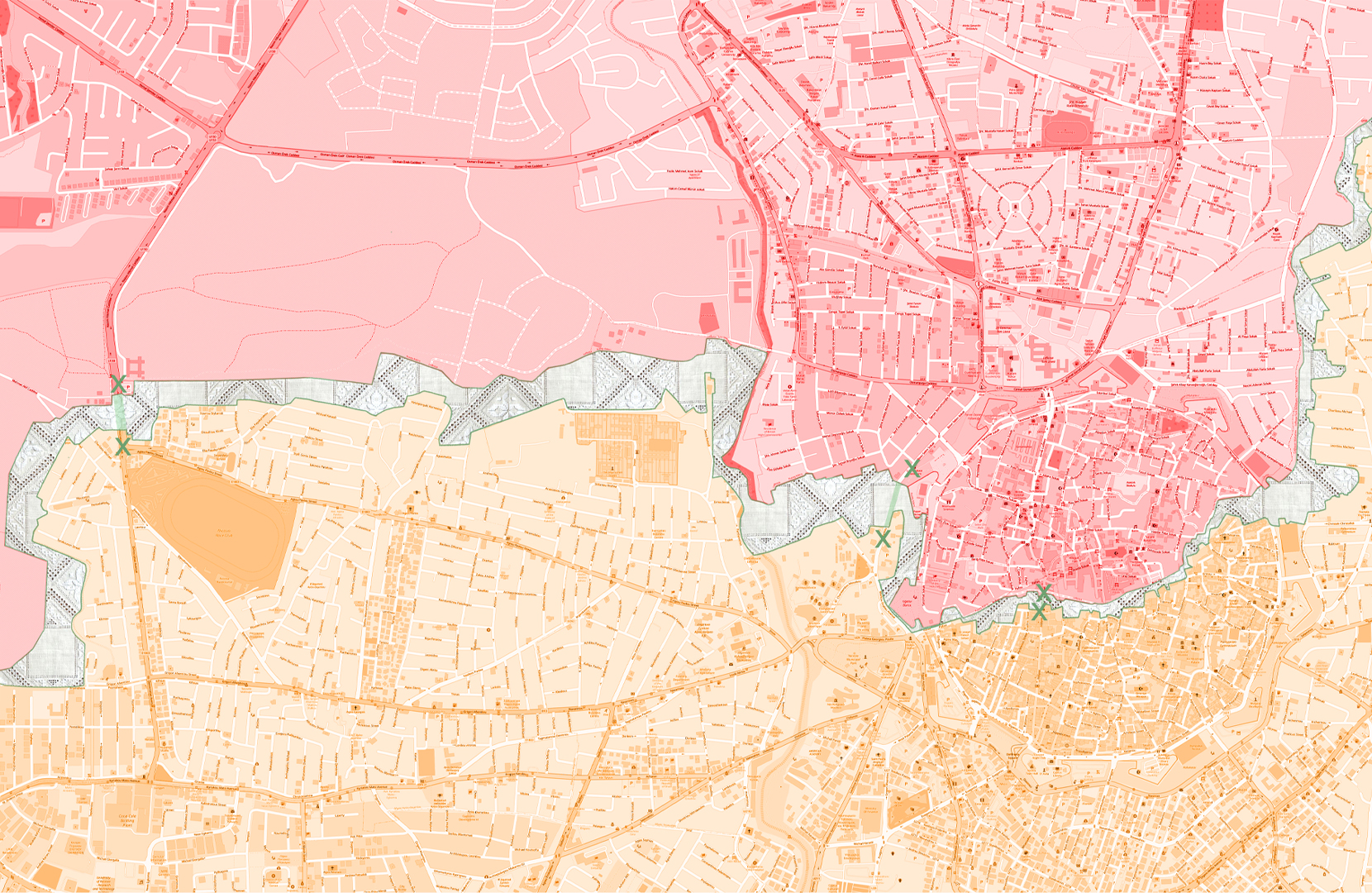

Turkish (Politician) Perspective: Green Line Scale

Turkish-dictated Cyprus, as it stands. A close-up representation of what the Turkish (politicians) believe is theirs.

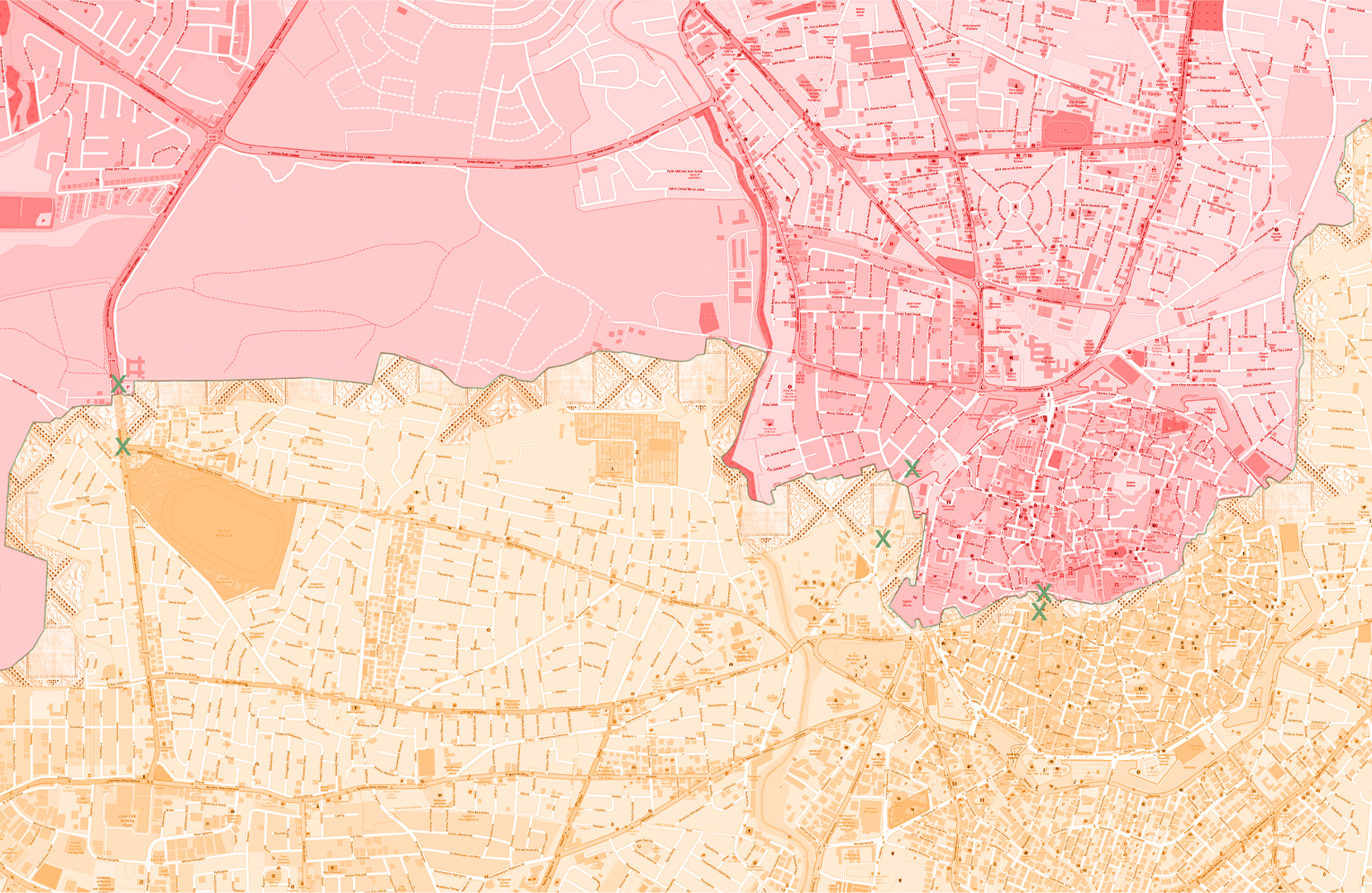

Cypriot Perspective: Green Line Scale

Greek-dictated Cyprus, as it stands. A close-up representation of what Greek-Cypriots understand as theirs, under the current circumstances. Although they believe in a unified Cyprus where all land is rightfully returned, the current circumstances (essentially, a geopolitical stalemate) call for a modified mapping of the Green Line. In this map, the southern portion of the Green Line is removed completely, and the demarcation between the Cypriot side and the Neutral Zone is erased, thus giving back as much land as possible to Greek-Cypriots.

De-Neutralizing the Neutral Zone

Since crossing points have opened between the north and south in 2003, peace-generating pop-ups have started to appear within the Buffer Zone. Co-working spaces promote collaboration between Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots, and media centers and NGOs host events such as screenings of peace-promoting films. These establishments are the beginnings of cultural and political change that show the neutral zone is no longer neutral—that its happenings are no longer predetermined by acts of colonialism or conflict, but by those who strive toward peace.

Conclusion

Nearly 50 years have passed since the invasion and subsequent fracture of the island of Cyprus. While tensions have eased and crossing points between the two sides have opened, reunification talks throughout the years have all ended in stalemates. Sentiments among the younger generations on both sides support a unified Cyprus and a future living together in harmony, yet politicians’ agendas prevail again and again. Despite the seemingly never-ending stalemate, it is critical that the ways in which the division of the island is represented have a seat at the table during these talks. We often assume maps are objective sources of truth, and final products not to be changed; however, under the circumstances of the Green Line in which the nuances of mapping become contested geopolitical grounds, the maps themselves must become subjective documentation of the world we want to see.

Northern Cyprus: Lands Unseen for 50 Years. Images of a view that may never be seen again by many Greek-Cypriots. Source: Jack Mac.

Bibliography

“Aging Grand Hotel Highlights the Ethnic Division in Cyprus.” AP NEWS, 26 Apr. 2021, apnews.com/article/nicosia-international-news-europe-cyprus-travel-199a790bddca4ab5a2faef84822070a4.

Byrne, Kolyn. “Nicosia International Airport - an Abandoned Airport in a Divided City.” World Abandoned, 22 Mar. 2017, www.worldabandoned.com/nicosia-airport.

Constantinides, Marie. “Ledra Palace: Dancing on the Line.” Mosaic, 4 June 2021, mosaic.gr/ledrapalace/.

“Hubris, Nemesis and Lies – Cyprus and the Downfall of the Greek Cypriots in 1974.” Www.t-Vine.com, www.t-vine.com/hubris-nemesis-and-lies-cyprus-and-the-downfall-of-the-greek-cypriots-in-1974/.

Jack Mac. “Cyprus in Film.” Bicycle Touring Apocalypse, jack-mac.com/cyprus-in-film.

Lepp, Billy Tusker Haworth, Catherine Arthur, Eric. “Graffiti in Cyprus Paints a Rich and Complex Picture of This Divided Society.” NEOS KOSMOS, 10 July 2019, neoskosmos.com/en/2019/07/11/news/cyprus/graffiti-in-cyprus-paints-a-rich-and-complex-picture-of-this-divided-society/.

“Military Histories - a Green Line Is Drawn.” Www.militaryhistories.co.uk, www.militaryhistories.co.uk/greenline/line2.

NEOS KOSMOS. “On This Day 46 Years Ago… Turkey Invades Cyprus.” NEOS KOSMOS, 19 July 2020, neoskosmos.com/en/2020/07/20/news/cyprus/on-this-day-46-years-ago-turkey-invades-cyprus/.

Sideridis, Dimitris. “Nicosia International Airport: The Cypriot Airport Abandoned for 44 Years.” CNN, 6 June 2018, www.cnn.com/travel/article/nicosia-airport-abandoned-cyprus/index.html.

Tiggerbird. “Exploring the Green Line in Cyprus.” Tiggerbird’s Travels, 21 Apr. 2019, www.tiggerbird.com/green-line-cyprus/.

“The Ledra Palace Hotel – Nonument.” Nonument.org, nonument.org/nonuments/the-ledra-palace-hotel/.

UNESCO. “UNESCO - Lefkara Laces or Lefkaritika.” Ich.unesco.org, ich.unesco.org/en/RL/lefkara-laces-or-lefkaritika-00255.

United Nations. “United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus: About” UNFICYP, 7 May 2014, unficyp.unmissions.org/about#:text=UNFICYP%20is%20one%20of%20the.