Geonarratives for Video Mitigation

0. INTRODUCTION

Our team collaborated with The Legal Aid Society for the past four months, joining and supporting their efforts to highlight the systematic barriers faced by low-income individuals and communities of color within the New York criminal justice system, and advocating for their clients’ sentence mitigation through videos and personal interviews. We contributed to their efforts by creating visual data narratives to supplement their video mitigation projects which aim for a range of outcomes including lessened incarceratory negotiated sentences, dismissals in the interest of justice, and release on recognizance instead of bail.

We created animated maps and illustrations that visualized the inequities faced by Legal Aid Society clients, all of whom are members of marginalized communities in New York City. Through applied geo-narratives (i.e. mapmaking) as a method for storytelling through “social geography”y,” we assisted the Legal Aid Society in visualizing how trauma, community, environment, and social factors “are linked to larger social forces that help or hinder their decision-making”.

Through this work, we also aim to examine how mass incarceration unfairly impacts marginalized communities and how these are processes grounded in geospatial realities.

1. LEGAL AID SOCIETY

The Legal Aid Society is a non-profit organization based in the United States that provides free legal services to low-income individuals and families who cannot afford legal representation. The organization was founded in 1876 and has offices throughout the country, with a primary focus on serving the needs of individuals and communities in New York City. The Legal Aid Society’s services include representation in civil, criminal, and juvenile rights matters, as well as advocacy for systemic change to promote fairness and justice in the legal system. During the four months, we have been in communication with the Legal Aid Society (LAS) on three specific criminal cases they are actively developing. Our role has included data acquisition, collaborating on concepts of visualizing racial and economic disparities with a hyper-focus on a case-by-case strategy to establish empathy for their incarcerated clients. It needs to be noted that much of the data, with which we have been working to construct the geo-narratives, is confidential, thus will be anonymized within this report.

2. THEMATIC CONCERNS

Mitigation for individuals currently incarcerated or at risk of incarceration is important because it can work to redress systemic inequities and promote restorative justice and equality in the criminal justice system. Literature on the prison industrial complex, like The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander (2010) highlights the transformation of Jim Crow era exclusion and oppression in the criminal justice system and its modern impact on marginalized communities, disproportionately affecting low-income individuals and Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities. Alexander writes in The New Jim Crow, “As a criminal, you have scarcely more rights, and arguably less respect, than a black man living in Alabama at the height of Jim Crow. We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.”

This systematic redesign is foundational to upholding white supremacy; structural racism and racial profiling have led to the violence and over-policing of particular neighborhoods, resulting in disproportionate rates of harassment, arrest, conviction, and sentencing of Black and Latinx people. Their entrapment in the carceral system perpetuates cycles of injustice and inequity, as highlighted by Kurgan’s “Million Dollar Blocks” (2013), which shows how the high concentration of incarceration in a few neighborhoods across New York City drains resources from those communities, disinvests public services such as education, housing, and healthcare, and creates barriers for individuals upon their release from prison.

Julie Urbanik specifies that the goal of mitigation “is to offer the client’s life story as justification for the most lenient sentencing available.” Mitigation can help to break this cycle of injustice and reduce recidivism rates by taking the geospatial and sociopolitical realities of their clients into consideration in their court case, unveiling and highlighting the underlying systemic issues while promoting equitable solutions for all individuals impacted by the carceral state. Geospatial mapping can assist through demonstrating “how clients’ lives are linked to larger social forces that help or hinder their decision-making (Urbanik).”

We’ve created spatialized narratives and/or histories of hardship to help contextualize the social, environmental, and economic influences on the life of LAS clients. The goal is to lend our skill sets to support the Legal Aid Society’s efforts in ensuring low-income and disadvantaged individuals and families have access to just and legal representation, but more specifically, in helping them establish mitigating circumstances for their clients. We hope that our work will be able to contribute in very material ways to the clientsmitigation cases. On the other hand, we also hope that our public facing work will be able to contribute to the larger conversations regarding restorative justice currently being practiced on the ground and future mobilization toward prison abolition.

3. CASE_1

Our first case involved the theme of housing instability and how living in multiple NYC shelters, being unhoused at times, attending various schools, and working multiple jobs could explain the higher likelihood of an individual being involved in the criminal justice system. As our work with the Legal Aid Society began, the client was in jail and awaiting trial. At the time we started collaborating with the Legal Aid Society, their video was already midway into editing and post-production. As such, we had less time to develop a polished process compared to the second case we would work on later in the semester. But to supplement the video interviews and narratives prepared by LAS, our mapping sought to visualize the “chaos” embedded in moving shelters and schools so frequently during the formative years of youth development.

As this was our first case, initial research was focused on understanding the situation at hand and developing a methodology which could also be applied to future cases. In addition to looking at data and satellite imagery of the relevant areas in the South Bronx, the group began searching for directions through which the narrative of an individual’s housing instability could unfold. The most challenging aspect of the early research was identifying new ways to show a lack of access to opportunities and resources, extenuating circumstances, or inequalities beyond surface level measures. Disparity of wealth, income, health, and opportunities across New York City is well-documented. On the other hand, asking what a “chaos map” would look like pushed our research to a much more personalized and micro-level scale.

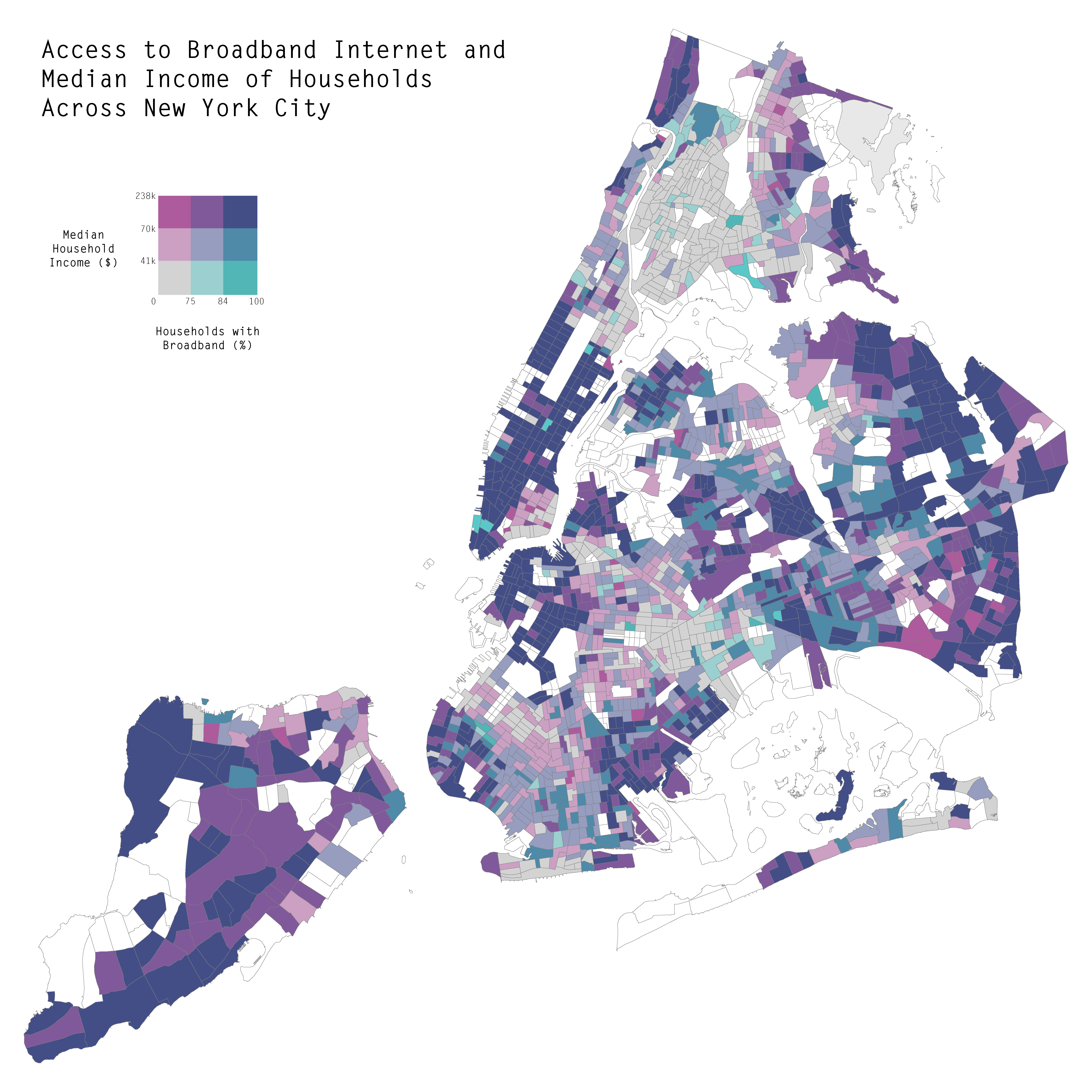

We later came across an article which revealed that shelters often lacked the necessary infrastructure for children to attend school remotely when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The number of households with broadband internet access in the Bronx, and especially within shelters, was notably lower compared to most neighborhoods across the five NYC boroughs. This fact can be critical for students that are awarded scholarships since some could not even log on to claim it, let alone attend college remotely. Though access to broadband internet is sometimes thought to be a given, lower income neighborhoods often see more trouble with internet reliability and/or buildings lacking the infrastructure ready to offer service.

The map above shows the bivariate data association between the median household income across New York and the percentage of households who have access to adequate internet. This formed the large-scale approach which we focused on, and subsequently studied more in-depth in a “chaos” map of an individual’s unstable housing. The map below originaly showed six approximate locations of the shelters that the client lived in and five locations of the schools he attended connected in sequence to illustrate the instability experience by the client, but as such information is confidential, the map has been censored here.

For pre-identified shelters and schools, we gathered other data points that helped highlight other “social forces” linked to the client (Urbanik). For each of the schools, we found a staggering percentage of students facing temporary/unstable housing situations ranging from 15% to nearly a third of all students. Meanwhile, a number of the homes and shelters were revealed to often be in squalid conditions. The Legal Aid Society video described low income families living in inhumane and illegal conditions, common issues with pests, lack of utilities, and mismanagement by building ownership. So our team decided to look into an online database of building violation reports provided by New York City Housing Preservation and Development’s and found numbers of past violations (which can include rat or cockroach infestations, broken heating, cooling, lack of water, plumbing, broken windows or tiles, leaks, etc.) for shelters specific to the case. Lastly, we included certain key life events and moments that were important to the case, bringing those together to create a personalized geo-narrative of the chaos in a client’s life.

4. CASE_2

Our second case for the LAS video mitigation team involved a young client based in the Mott Haven neighborhood of the Bronx. The goal was to have the client released and ensure he was spared a criminal record. Unlike the previous case, the video mitigation team of Legal Aid Society along with Fordham Law School students, were in the early stages of developing their case and had yet to start the interview process. They were able to share case information in which we developed a broader narrative around the social, environmental, and economic factors which exacerbate opportunity inequality across New York City.

Through the concept of opportunity mapping, a research tool developed by the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, we began to analyze the contributing factors which determine opportunity, equity, and sustainability within New York City through educational, economic, community, and health metrics. The Kirwan Institute notes that “for many marginalized communities, particularly low-income communities and segregated communities of color, neighborhood conditions limit access to opportunity and advancement” (Reece). We found this to be supported by our data findings as the Bronx and Community District 1, ranked as one of NYC’s most opportunity isolated areas. For young people, this geographic isolation from opportunity can create barriers to improvement, hinder their quality of life, and stifle potential for success.

As our research and the mitigation narrative developed, our focus turned to youth disconnection as a barometer for a community’s health and wellbeing as disconnection, poverty and violence often co-exist and persist in the same areas. In 2021, nearly 11 percent of young people 16–24 years of age in the US were not engaged in either school or the workforce, defined as disconnected youth or opportunity youth by Measure of America and The Aspen Institute respectively. In densely populated New York City, vastly different youth disconnection rates can be found just miles apart. Although the Bronx already has the highest youth disconnection rate among the five boroughs at 18.25 percent versus the city average of 13 percent, its southern Community District 1, which includes Mott Haven, has one of the highest rates of youth disconnection at 25 percent.

Risk for youth disconnection is also inequitably distributed across racial and ethnic groups. Opportunity youth remain over-represented by Black and Latinx communities, signaling structural racism contributes to disconnection. Nearly one in three opportunity youth live in poverty and are more likely to experience the compounding risk factors that accompany living in areas of concentrated poverty, including but not limited to more widespread police contact and higher rates of gun violence. The video below (fig. 4) will be used to support the LAS geonarrative which visualizes the association between the data fields described above with youth disconnection in New York City.

5. TAKEAWAYS

Privacy concerns: The Legal Aid Society deals with sensitive legal matters involving clients, and there may be privacy concerns around sharing location-based data in the public domain. It is important to ensure that any data shared does not compromise the privacy of clients or expose them to any risks.

Data accuracy and completeness: Legal Aid Society cases can involve complex legal issues, and the data used to create mapped geonarratives must be accurate and complete. You will need to ensure that the data used is up-to-date and that you have access to all the relevant information needed to create a comprehensive geonarrative.

Collaborating with non-GIS professionals: You may need to collaborate with non-GIS professionals, such as lawyers, paralegals, and community organizers, who may not have a technical background. It is important to communicate effectively and ensure that the geonarratives meet the needs of all stakeholders involved in the project.

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, Michelle, and Cornel West. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New Press, 2010.

Fischer, David. “Connecting Our Future: 2020 Disconnected Youth Task Force Report.” Nyc.gov, NYC Disconnected Youth Task Force, 2020, www.nyc.gov/assets/youthemployment/downloads/pdf/dytf-connecting-our-future-report.pdf.

Kurgan, Laura. Close up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics. Zone Books, 2022.

Lewis, Kristen. “A Disrupted Year: How the Arrival of Covid-19 Affected Youth Disconnection.” Meaureofamerica.org, Measure of America, 2022, measureofamerica.org/youth-disconnection-2022/.

NYC Department of Education, 2018-2019 Students in Temporary Housing School Level Report, January 22, 2019. Distributed by NYC Open Data. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Education/2018-2019-Students-in-Temporary-Housing-School-Lev/8iee-pzu6.

NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), Housing Maintenance Code Complaints, January 14, 2014. Distributed by NYC Open Data. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Housing-Development/Housing-Maintenance-Code-Complaints-uwyv-629c.

Office of Technology and Innovation (OTI), Internet Master Plan: Adoption and Infrastructure Data by Neighborhood, March 12, 2021. Distributed by NYC Open Data. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Internet-Master-Plan-Adoption-and-Infrastructure-D/fg5j-q5nk.

U.S. Census Bureau, MEdian Household Income by Census Tract, 2014-2018 American Community Survey, table DP03, DATA2GO.NYC, accessed March 6, 2023. https://data2go.nyc.

Reece, Jason, et al. “Place Matters: Using Mapping to Plan for Opportunity, Equity, and Sustainability .” Kirwanninstitute.osu.edu, Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, 2012, kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/opportunity-mapping-issue-brief.

Swaner, Rachel, et al. “Gotta Make Your Own Heaven: Guns, Safety, and the Edge of Adulthood in New York City.” Innovatingjustice.org, Center for Court Innovation, Aug. 2020, www.innovatingjustice.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2020/Report_GunControlStudy_08052020.pdf.

Urbanik, Julie. “Applied Geonarratives: Arts-Based Social Geography in Criminal Defense Mitigation.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4, no. 1 (May 11, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100159.