Units of Study: The Complex Landscape of a New York City Reading Curriculum

ABSTRACT

Reading methodology in the United States has been in flux for the past 100 years, with many methods to aid and instruct young children vying for dominance. Though phonics based reading has been a classically prominent methodology, balanced literacy, or contextual reading, has been tested since the 60s. A contemporary curriculum – Units of Study, devised by Columbia Teachers’ College professor Lucy Calkins in 2002 – is currently experiencing a heated critique in light of its widespread use and noticeable lack of efficacy.

Beginning in 2003, the Units of Study curriculum used New York City public schools as a testing ground. Thus, New York City was chosen as a site of analysis that explores the question: can critics pin the difficulty of literacy education on one curriculum? The research specifically considers the geography of literacy rates in New York City and uses geographically-weighted regression analysis to assess the influence of key reading curriculum, demographic, economic, and funding-related indicators to language and reading proficiency, as measured by English & Language Arts (ELA) test scores in New York City public elementary schools in 2019.

We found that Units of Study exhibits no correlation with ELA results, prompting the question: why is the media linking Units of Study to failed literacy? Through the following discussion, we posit that shifting curriculums are not the answer to solving low literacy rates. Curriculum shifts are treated as a band-aid solution by politicians vying for better literacy scores, and can at times destabilize meaningful progress by hasty course-correction. Rather, it will take long-term action against systemic poverty and education underfunding to reverse these concerning trends.

WHAT IS UNITS OF STUDY?

Despite varied efforts to improve literacy rates in the United States, two-thirds of fourth graders do not demonstrate reading proficiency in 2023. Why does the U.S. rank so poorly in literacy? What is the country doing wrong?

In recent years, opinion pieces have pointed towards one particular literacy program, Units of Study, as the root cause of this deeply concerning American failure. Developed in 2002 by Lucy Calkins, a founding director of Columbia’s Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, Units of Study rests on the assumption that children are natural readers, using a balanced literacy approach of teacher-led reading and writing instruction and independent learning. It’s been estimated that around a quarter of the country’s 67,000 elementary schools use the curriculum (Goldstein, 2022).

Parents and teachers who support the “science of reading” approach have criticized the program, instead advocating for a reading comprehension curriculum that better incorporates phonics and linguistic comprehension. Fifty years of research has revealed the effectiveness of phonics, those sound it out exercises that are purposefully sequenced, in literacy instruction (Ibid). While Units of Study includes some phonics instruction, critics argue that it is not enough to help struggling readers. The inflexibility of the program has also been cited as a key concern, as it is designed to be used with all students in a classroom, regardless of their reading level or ability. Some have argued that this one-size-fits-all approach is not effective for all students, and struggling readers may require more individualized instruction and support to help them catch up with their peers.

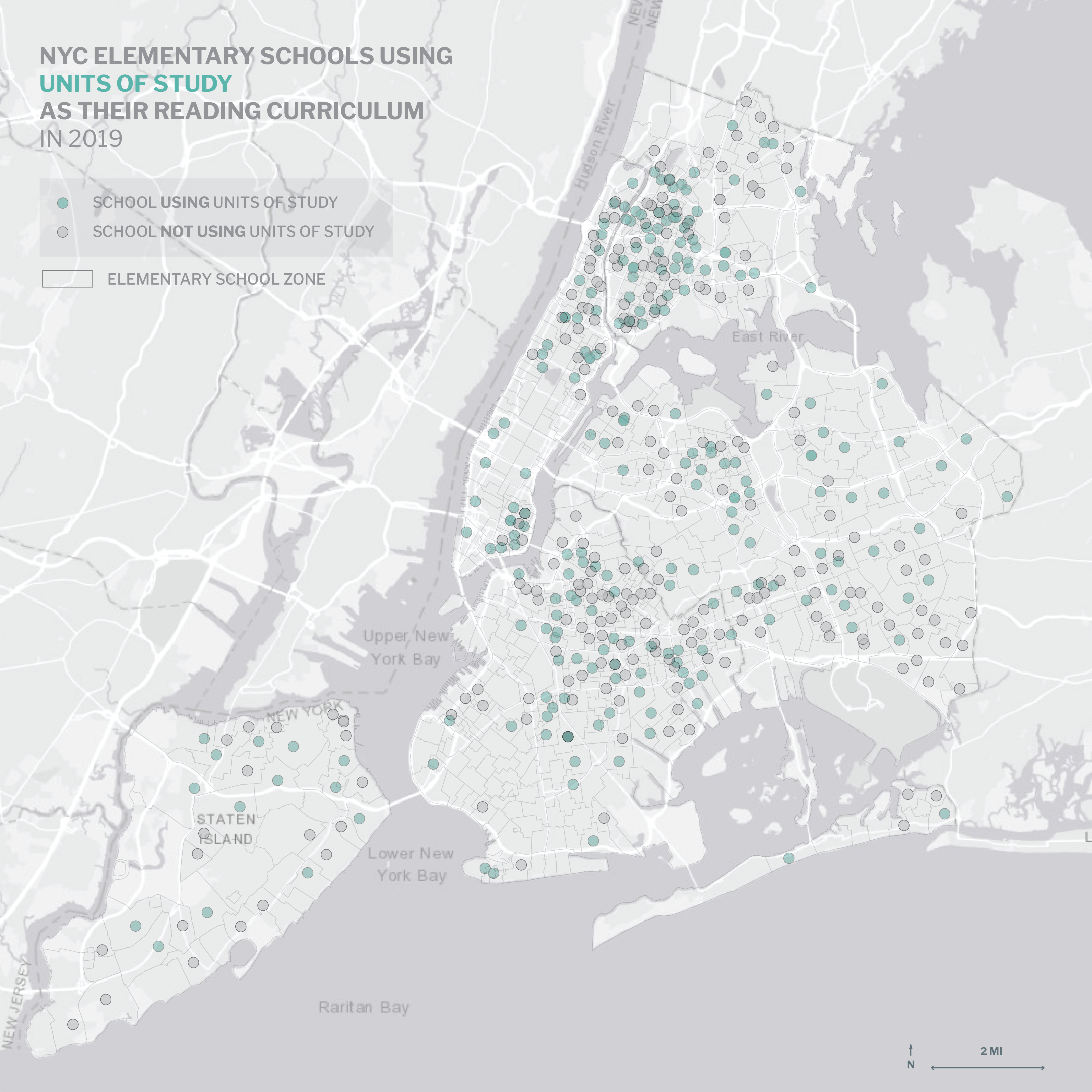

To better understand this ongoing debate, this research focused on New York City, where balanced literacy gained momentum in 2003 under Mayor Bloomberg and led to implementation of the program in a majority of the city’s elementary schools under Chancellor of Education Joel Klien. Balanced literacy proponents from Teachers College were well-represented in the higher ranks of the D.O.E. at the time, furthering the curriculum’s support. However, by 2008, the influence of the curriculum began to wane, as Klein lost interest following unchanged reading scores (Winter, 2022). But in many of the schools that already invested their massive amounts of time and money into the program, the curriculum has continued. In 2019, 49% of New York City elementary schools were using Units of Study in some capacity, as shown through the map below.

The program is pricey, from 2016 to 2022 NYC paid $31 million for services from the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project (Goldstein, 2022). The question thus remains: Why keep running an expensive curriculum that may, at best, be neutral in terms of affecting early literacy rates, and at worst, be harming young students who aren’t fit for the program?

This issue goes beyond mere pedagogical differences. At its core, the disagreements over Units of Study revolve around issues of equity and educational access. Literacy, or lack thereof, can be a considerable source of conflict in urban spaces. Only 63.8% of all NYC public school students exhibited reading proficiency in 2021, prompting city and state officials to question the efficacy of schools’ current literacy programs (NYSED, 2023). Low-literate children often become low-literate adults, who are subsequently at a greater risk of low self-esteem, lower incomes, limited access to professional development, and potential isolation (Literacy Pittsburgh).

In regions as linguistically diverse as New York, understanding how literacy is taught can be understood through the framework of language ecology. First defined by Einar Haugen in 1971, language ecology is described as “the study of interactions between any given language and its environment” (Nettle & Romaine, 2002). Language ecology, thus, considers how traditional components of linguistics — sociolinguistics, philology, linguistic demography — intersect with one another. The environment through which language is learned is important, as are the methods that are used. These are the components of language ecology that we are interested in understanding on a spatial level.

Conflict emerges from spatial inequities on a daily basis, playing out in schools, workplaces, and on the streets. Low-literacy rates can limit civic participation and community involvement, as residents may have limited access to information. The potential sources of conflict that may arise from language learning are vast and understudied, making our project increasingly important.

By studying the spatial dynamics of literacy rates in urban areas like New York City, we may be better able to assess potential connections between other socioeconomic, mental, and physical health outcomes as well as the resources certain neighborhoods may have better access to that may aid their language learning.

RESEARCH QUESTION

To investigate the impact of Units of Study on New York City reading levels, we explore the question: How are student literacy rates affected by diverse student backgrounds, school funding allocations, and reading curriculums in New York City elementary schools?

METHODOLOGY

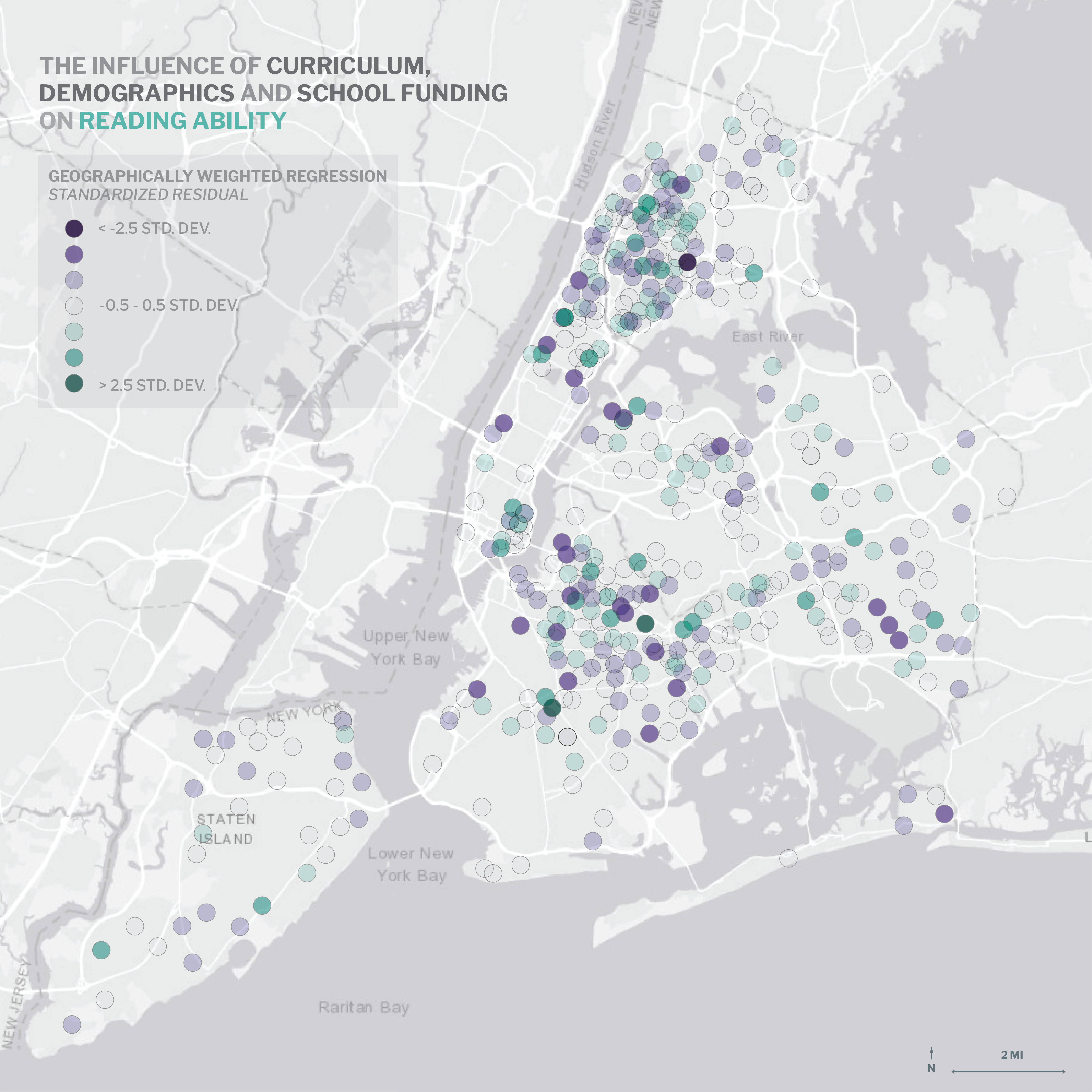

To assess our research question, we ran a geographically-weighted regression analysis, a “spatial analysis technique that takes non-stationary variables into consideration (e.g., climate; demographic factors; physical environment characteristics) and models the local relationships between these predictors and an outcome of interest” (Population Health Methods, 2023). This method provides a useful vehicle for analysis to assess our research question as it allows for localized, school-level understanding of the influence of key reading curriculum, demographic, economic, and funding related indicators to language and reading proficiency, as measured by English & Language Arts (ELA) test scores in New York City public elementary schools in 2019.

In the geographically weighted-regression, our dependent variable was school-level elementary student ELA scores; our dependent variables were diverse student backgrounds as measured by race and economic need, school funding allocations per pupil, and finally each school’s reading curriculum. All data was sourced from publicly available New York City and New York State Department of Education databases.

As shown in the map below, the regression looked at each school’s ELA performance as a function of its unique demographic, funding and curriculum conditions, denoting which schools over- or under- performed with a standardized residual. A standardized residual is just the difference between observed and predicted values based on the statistical model. Negative residual values (in purple) indicate schools that underperformed on ELA tests based on their conditions, while positive residual values (in green) indicate schools that overperformed on ELA tests based on their conditions.

In terms of our research question, the geographically-weighted regression also allowed us to analyze relationships between variables to understand which dependent variables had the strongest relationship with ELA results. It’s also important to note that the measurement of literacy via ELA results is imperfect as many teachers are instructed to “teach to the test,” so the test results do not reflect true reading ability.

WHAT DID WE FIND?

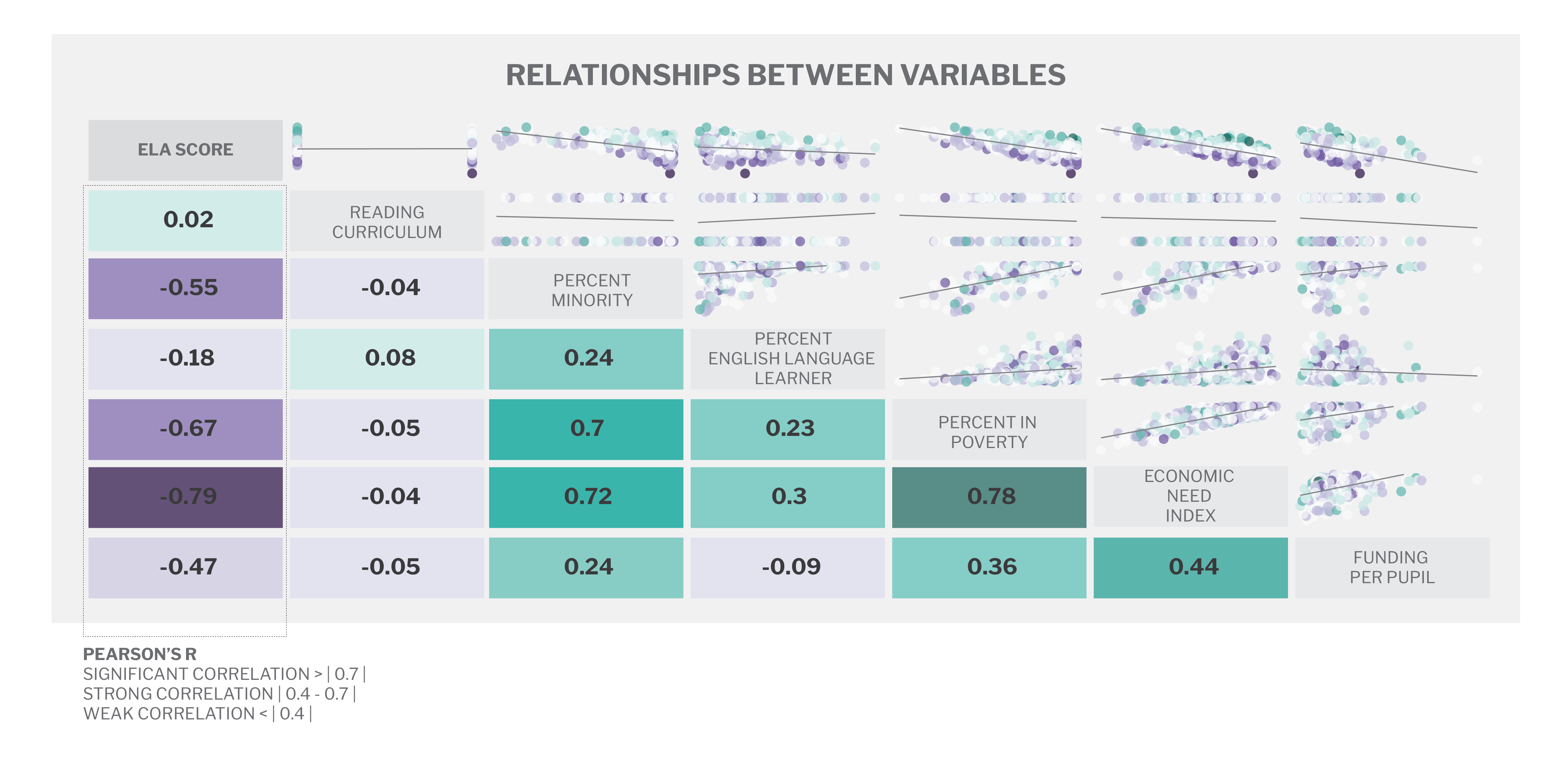

Reading curriculum exhibits no correlation with ELA results, leading us to question the alarm with which the media is linking Units of Study to failed literacy. In this case, the most significant correlation with ELA results was economic need index (which estimates the percentage of students facing economic hardship). Other strong relationships were between percent of students in poverty, percent of minority students and school funding per pupil. This graphic shows each variable relationship as Pearson’s R correlation coefficient which is a measure of relationship strength. Pearson’s R values range on a scale between -1 and 1 – values with an absolute value of 0.7 or greater typically representing a significant positive or negative correlation.

To go a step further, we wanted to control for demographics, and look at how literacy rates compare between New York City schools that have and have not employed Units of Study as a reading instruction tool?

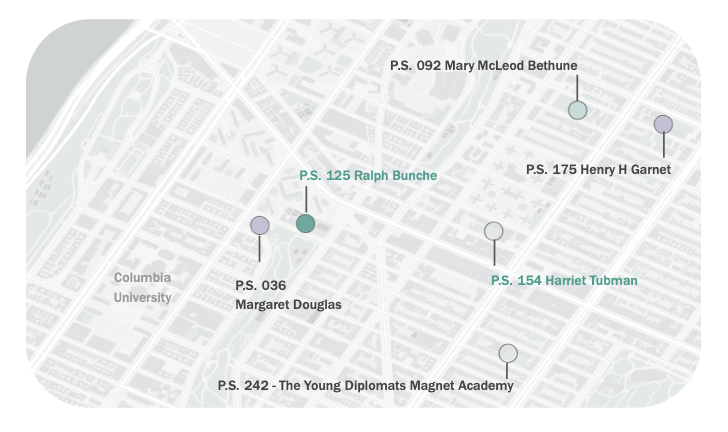

To do this, we zoomed into the Morningside Heights area of School District 5 as shown below.

This case study area, right near Columbia’s campus, includes 6 elementary schools:

Out of these 6 schools…

- 2 used Units of Study, with a 50% overperformance rate

- 4 did not use Units of Study, with a 25% overperformance rate

We then compared two of these elementary schools, just a 3 minute walk from one another.

Case Study 1: P.S. 036 Margaret Douglas The first case study school is P.S. 036 Margaret Douglas, which does not use Units of Study and underperformed in terms of its literacy score and unique conditions by a residual of -1.

Case Study 2: PS 125 Ralph Bunche The second case study school is PS 125 Ralph Bunche, which did use Units of Study and over-performed in terms of its literacy score and unique conditions by a residual of +2. With a lower economic need, lower funding per pupil, and higher percentage of English language learners, how did Bunche exceed the results so substantially? Was it merely a factor of economic need or was Units of Study actually helpful for Bunche students?

Using these case studies as a framework, it’s not apparent that reading curriculum i.e. Units of Study is the causal factor of student literacy. It might be more of a complex web of factors, including student economic conditions, classroom funding, etc. Instead of blaming the curriculum, it might be more worthwhile for NYC DOE to understand how systems of poverty and school funding influence student performance and literacy.

CAN UNITS OF STUDY BE BLAMED?

Through this research, we sought to make an argument about the geography of literacy education in New York City. Initially, we believed there might be a connection between reading curriculums and literacy rates. Upon finding an insignificant relationship, we returned to the question that sparked our attention: What’s all the alarm about if our data shows that the program has a neutral effect at worst? We wanted to dig deeper and see if this negative media correlated with anything else.

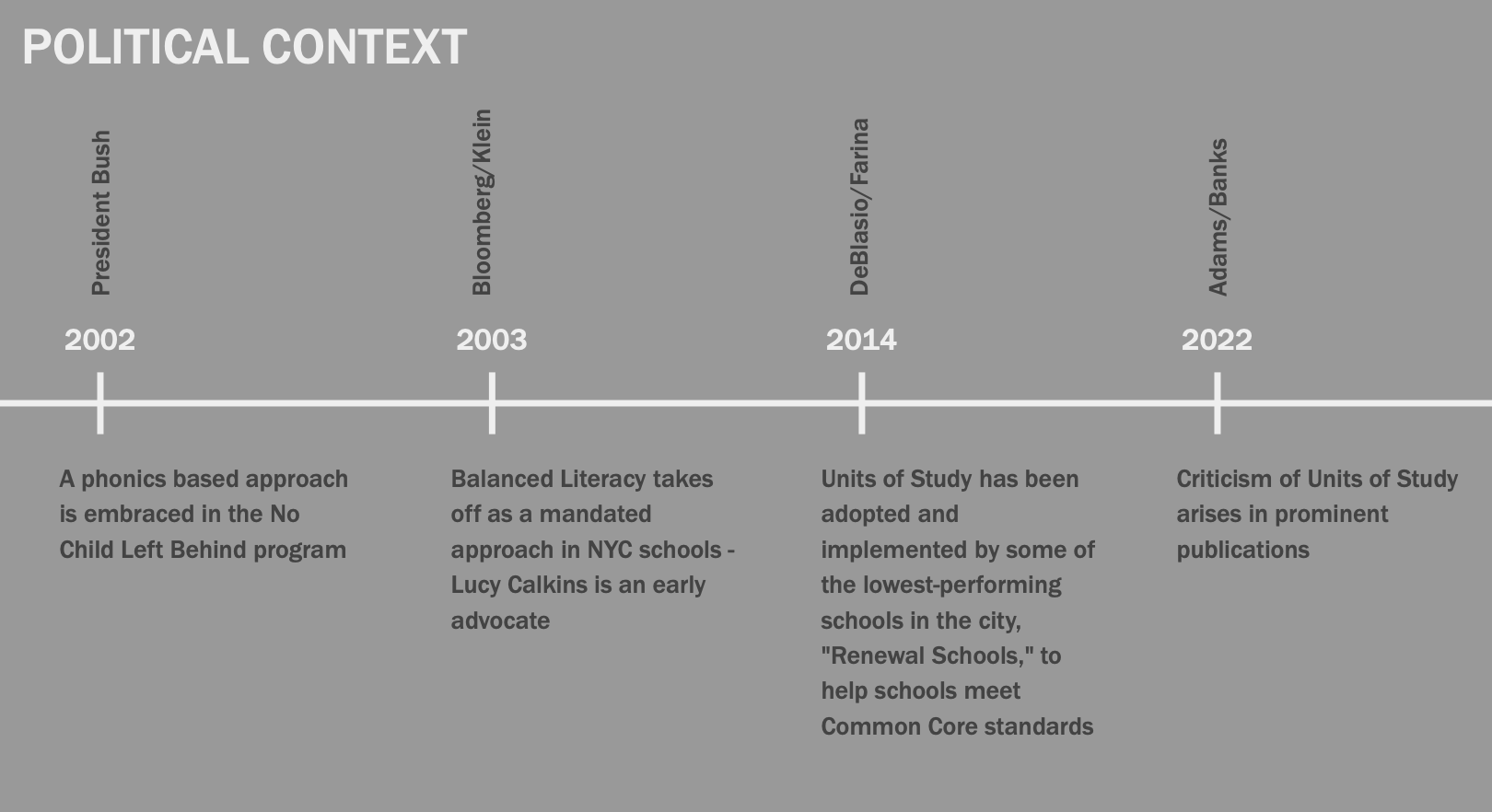

Looking at a timeline of Units of Study’s popularity, we see a direct correlation with the Mayoral and School Chancellor changes. The school chancellor in 2014, Carmen Farina, pushed for a sweeping wave of implementation at low performing schools to try and raise them up to standard criteria. But, by 2022 scores hadn’t shifted enough, and current Chancellor David Banks has become a strong critic of Units of Study.

If we look through the headlines and instead at the context and data, what we’re seeing here isn’t a very faulty curriculum. Instead, we see a target to blame for continuously low literacy rates in a very complex system of factors. Perhaps ever shifting and expensive curriculums aren’t the answer here. A NYC public school teacher we interviewed chimed in that, “There isn’t much time to train teachers in the new curriculum and none of them are given enough time to really test their efficacy.” These switches seem like a detriment to teachers ability to plan and course correct based on their own experience, rather mandating broad adoption of programs based on political motives.

Curriculum shifts are treated as a rapid solution or a scapegoat by policy makers - but in the wide network of sociopolitical issues that actually impact literacy, curriculums prove to be neither. The media’s vilification of this curriculum instead seems linked to political motives - it certainly doesn’t hurt to have a “failing” expensive curriculum to point to in relation to hundreds of millions of dollars in cut funding.

In sum, our study has found Units of Study not nearly as guilty as it seems. Instead, larger systemic issues are still the obvious indicators of low literacy issues. This problem is certainly not helped by the treatment of curriculums as quick-fix solutions. There is no quick fix solution, and instead the government must do the harder work of tackling systemic poverty and underfunding to see real progress.

WORKS CITED

A - districts: Nysed Data Site. data.nysed.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://data.nysed.gov/lists.php?type=district

Calkins, Lucy. “Units of Study Reading, Writing &; Classroom Libraries by Lucy Calkins.” Lucy Calkins and Colleagues Units of Study. Heinemann Publishing. https://www.unitsofstudy.com/.

“Comparing Reading Research to Program Design: An Examination of Teachers College Units of Study.” Achieve The Core. Student Achievement Partners, January 2020. https://achievethecore.org/page/3240/comparing-reading-research-to-program-design-an-examination-of-teachers-college-units-of-study.

Goldstein, D. (2022, May 22). In the fight over how to teach reading, this guru makes a major retreat. The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/22/us/reading-teaching-curriculum-phonics.html

Kristof, N. (2023, February 11). Two-thirds of kids struggle to read, and we know how to fix it. The New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/11/opinion/reading-kids-phonics.html

Literacy Pittsburgh. “The Challenges of Low-Literacy.” Literacy Foundation. https://www.literacypittsburgh.org/the-challenge/

Meko, Hurubie. “Court Leaves New York City School Budget Cuts in Place.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 22, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/22/nyregion/new-york-city-school-budget-cuts.html.

Nettle, D., & Romaine, S. (2002). Vanishing voices: The extinction of the world’s languages. Oxford University Press.

New York City Public Schools. New York City Department of Education. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.schools.nyc.gov/.

Population Health Methods. “Geographically Weighted Regression.” Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/geographically-weighted-regression

“The Debate over the Best Way to Teach Reading.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 4, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/04/opinion/letters/reading-phonics.html.

The challenge: Causes of low literacy. Literacy Pittsburgh. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.literacypittsburgh.org/the-challenge/

Winter, Jessica. “The Rise and Fall of Vibes-Based Literacy.” The New Yorker, September 1, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-education/the-rise-and-fall-of-vibes-based-literacy.

Zimmerman, Alex, and Yoav Gonen. “Hundreds of NYC Elementary Schools Used a Teachers College Reading Curriculum Banks Said ‘Has Not Worked’.” The City. The City, February 14, 2023. https://www.thecity.nyc/2023/2/14/23598696/nyc-teachers-college-lucy-calkins-balanced-literacy-david-banks.