Redefining Homogeneity: Marriage Migration in Rural South Korea

Once a country known for its homogeneity, South Korea’s population is no longer homogeneous. Over the past 30 years, South Korea’s highest in-migration rate has been through marriage. Primarily women from southeast Asian countries – China, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Cambodia – have been encouraged by government-sponsored subsidies to get married in South Korea. This ‘marriage migration’ was driven by the considerable numbers of unmarried men in rural towns, resulting from fast economic growth and internal migration by rural women to urban areas. The migrant brides, in turn, have created economic and cultural links between Korea and their home countries. This cultural and social phenomenon(Onishi 2008), this movement has vast implications and impacts on the future of this country and on what it now means to be identified as “Korean.”

This project investigates these international and domestic scale movements; they reveal a spatial complexity created by marital cultures and local policies, all ultimately driven by economic necessity.

Domestic Migration in South Korea: 1970s and Onward

click here for full screen view of this map

Scroll map of internal migration within Korea over the years (1970-2020). Source: kosis.kr

Since the Korean War, South Korea has been experiencing tremendous and steady economic growth. In 2022, it is now the 10th largest world economy. The drastic increase in its national GDP from the 80s till now was coined the “miracle on the Han River.” Along with the economic growth, a mass country-wide migration from rural to urban areas has been ongoing. As a result, more than 50 percent of the national population now lives in the Seoul metropolitan area, which accounts for only 0.6 percent of the country’s land area.

click here for full screen view of this map

Swipe map of population overtime (1970 v.s. 2020). Source: kosis.kr

Despite these recent economic changes and rural-urban migration, social life in South Korea remains embedded in Confucian culture, especially in rural areas, where the emphasis is placed on family and kinship. The patrilineal Confucian definition of the family has an immense impact on domestic migration across Korea. Confucianism underscores that filial piety is a cardinal virtue and that marriage and procreation are the eldest son’s most important social obligations. (Hsu 61)

A traditional Korean nuclear family, according to Confucianism values, has four formal criteria:

- The nuclear family 가 (家).

- The family’s formal head Hoju 호주 (戶主), the oldest man in the family, holds significant rights and privileges.

- The successor to the head-of-house 호주계승 (戶主繼承), which is the eldest son.

- The estate is considered family property 가산 (家産).

This Korean nuclear family is ruled entirely patrilineally, where the prominent family unit is the direct line of descendants 친족 (親族). Other relatives through female kinships are considered outside family 외갓집 (外家). Therefore, when a daughter marries, she will be immediately called “an outsider,” leaving the family unit. In other words, she joins her husband’s family and is responsible for her domestic duties, including serving him and his parents, thereby maintaining traditional family customs and reputations.

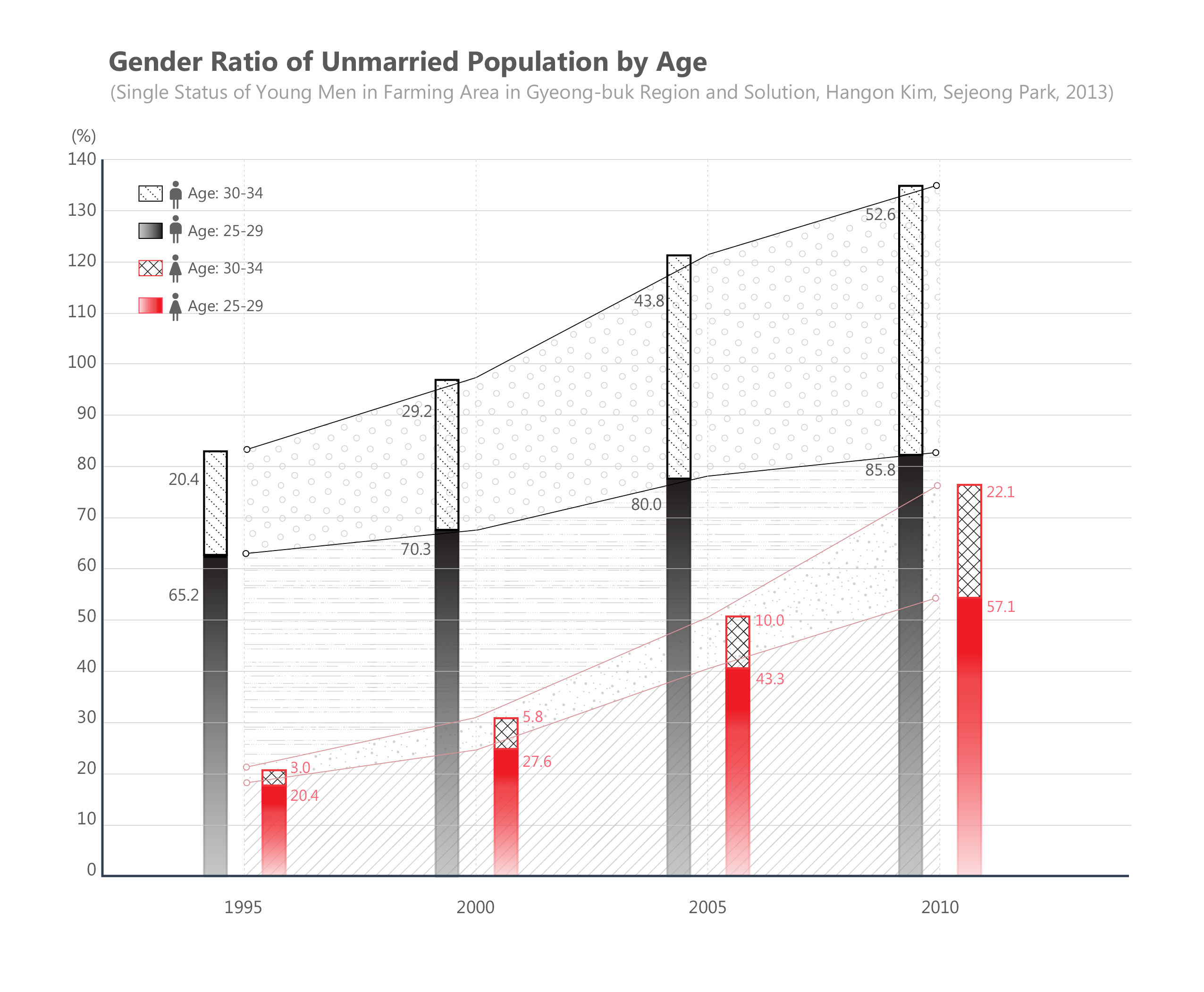

Because of these traditional family practices, more men remain in rural areas than women, contributing to the decline in birth rate that has persisted in Korea since the 60s. The gender imbalance in rural South Korea caused a sharp drop in population in rural towns. As a part of the revitalization program of those rural municipalities, local governments started to provide subsidies for ‘marriage migration,’ and therefore to foreign brides, starting in the 90s.

International Marriage Migration to South Korea

click here for full screen view of this map

Marriage migrants to Korea 2020. Source: kosis.kr

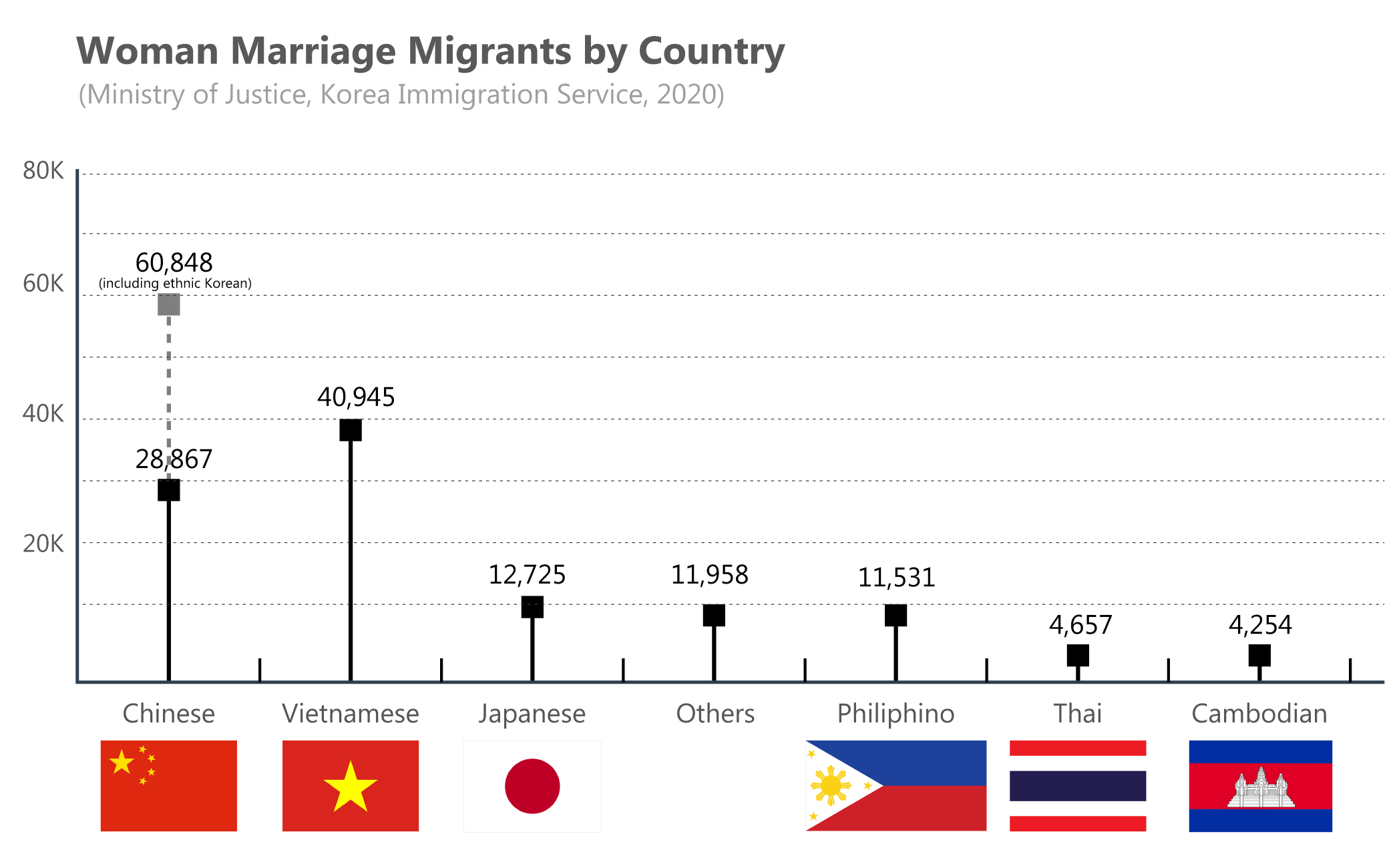

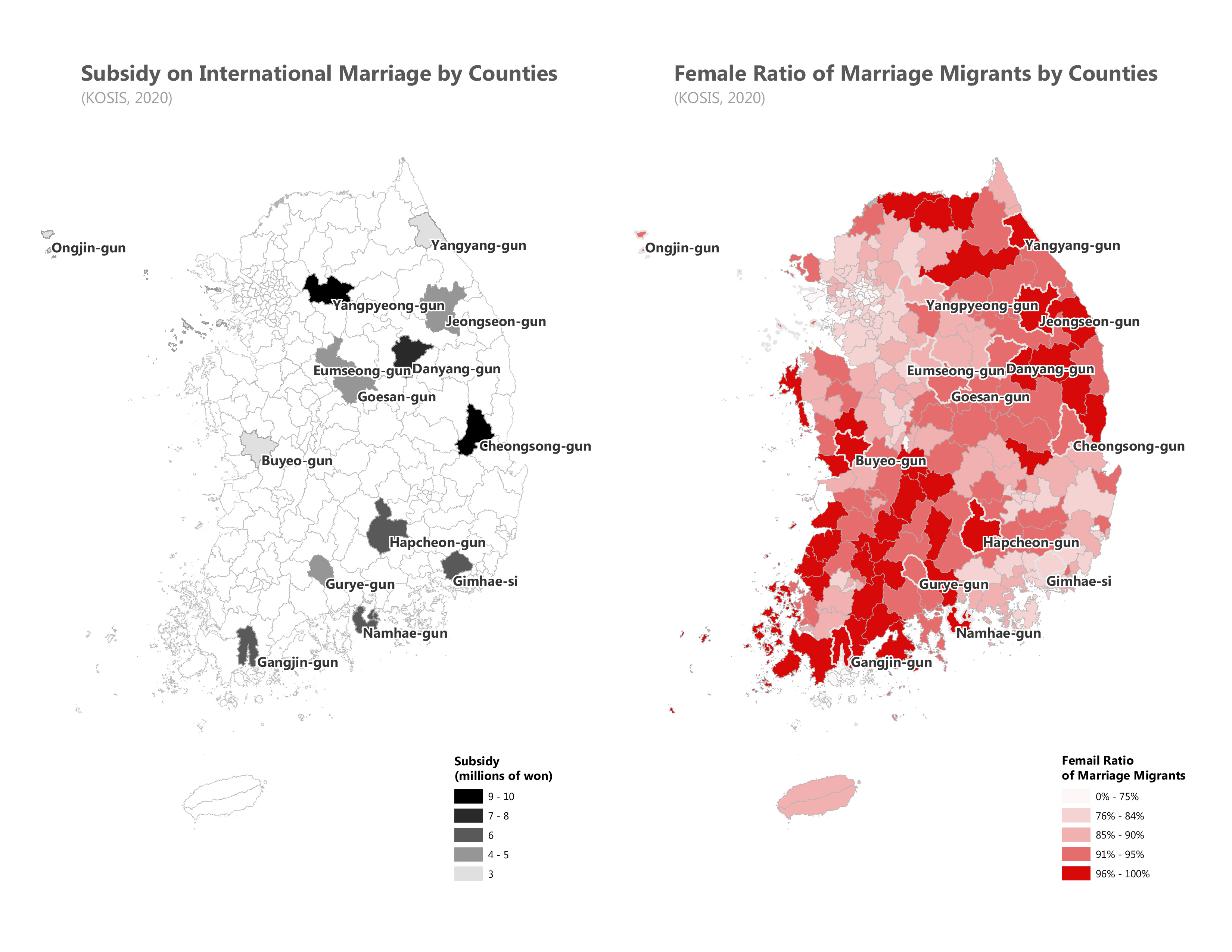

In the 1990s, 35 rural municipal governments started subsidizing private marriage brokers to introduce unmarried male farmers to ethnically Korean women in China and women from other Asian countries, paying the brokers 4 to 10 million Korean won (back then, around $3,800 to $12,000) per marriage.

These policies were established in an attempt to address the aging population by encouraging these unmarried men to find a wife and eventually reproduce to increase population growth. However, after 30 years of this practice, in 2021, government subsidies started to be removed. As a result, in South Korea, between 2000 and 2005, such marriages increased almost fivefold, from 6,945 to 30,719 (Korea National Statistical Office 2011a). Now bolstered at more than 334,000, these marriage migrants (immigrants and naturalized by marriage) account for 16.7 percent of all immigrants in South Korea. Renowned as a monoethnic country, Korea is now demographically and politically shifting towards becoming a multi-ethnical society.

However, these political movements and economic subsidies supporting marriage migration are not 100% celebrated and, in fact, have an adverse effect. Marriage migrants report facing higher levels of domestic and social conflict. They are isolated from their home countries and remain disadvantaged in these new environments. Furthermore, they tend to face more economic difficulties since more men from rural lower-income brackets seek help from marriage agencies for foreign brides. A study conducted by Ewha Womans University in 2022 has found that “…immigrant women in patriarchal households were more likely to be depressed … poorer life satisfaction … and poorer marital satisfaction … than women in martially equal households.” (PLOS ONE 2022)

Marriage migrants have also been expected to maintain the patriarchal hierarchy by acting as compliant and submissive wives, limiting their career growth and eventual integration into Korean society. Language barriers, cultural differences, and financial dependencies contribute to the characteristic isolation these new immigrants face in the so-called homogenous society in which they have: ‘…marriage migrants play multiple roles - as mothers, domestic workers, caretakers, and family helpers.” (Piper and Roces 2003)

The Story of Pham, from Vietnam to Cheongsong County

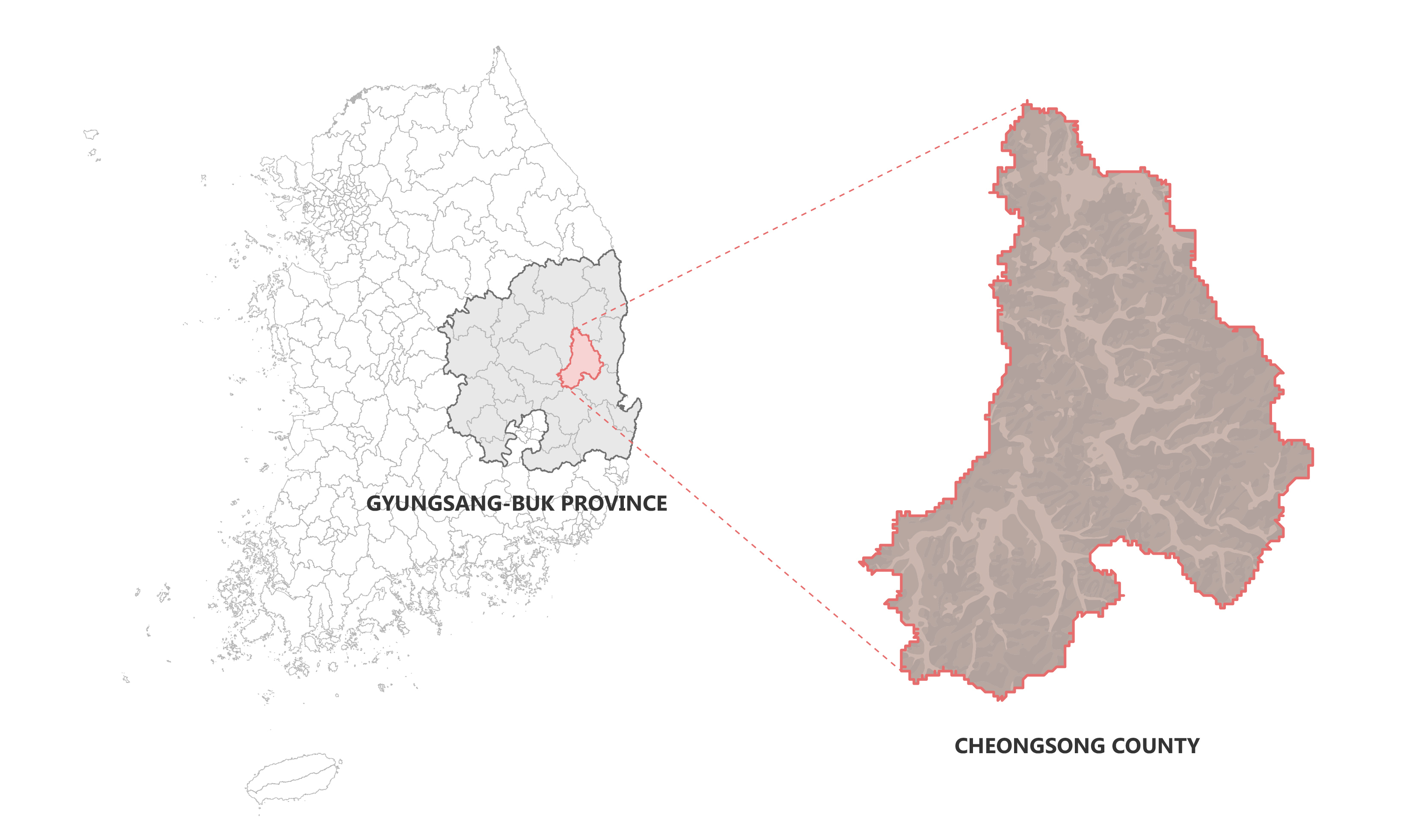

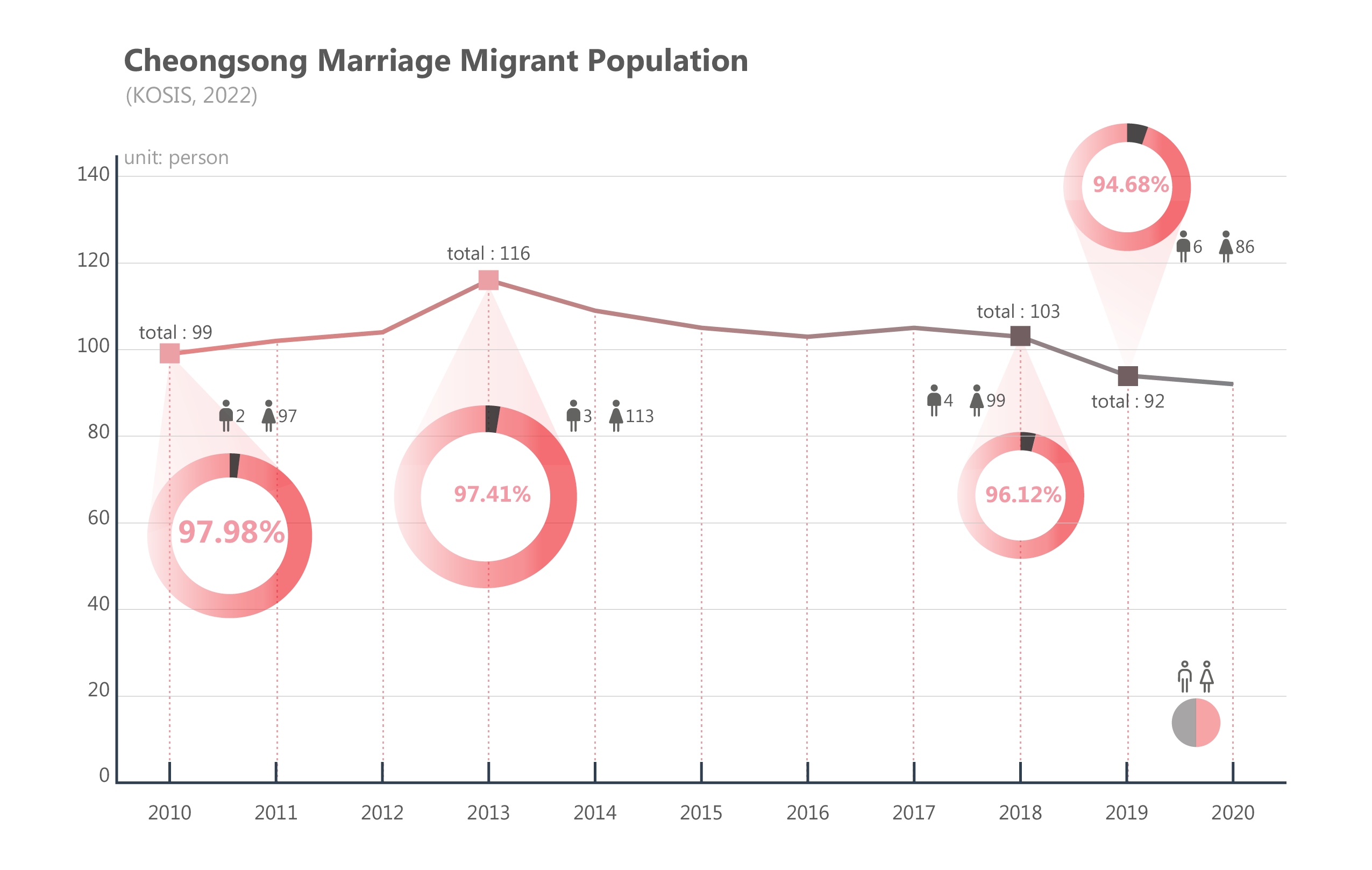

Cheongsong County, a county in Gyungsang-buk Province, has an influx of marriage migrants, which make up more than 69 percent (160 of 231) of the foreign residents in the municipality. Among them, the overwhelming proportion is women. Additionally, Cheongsong County, a rural area of the province, was one of the counties that sponsored the most significant subsidies (up to 10,000 dollars per case) for international marriage as a part of rural revitalization policies.

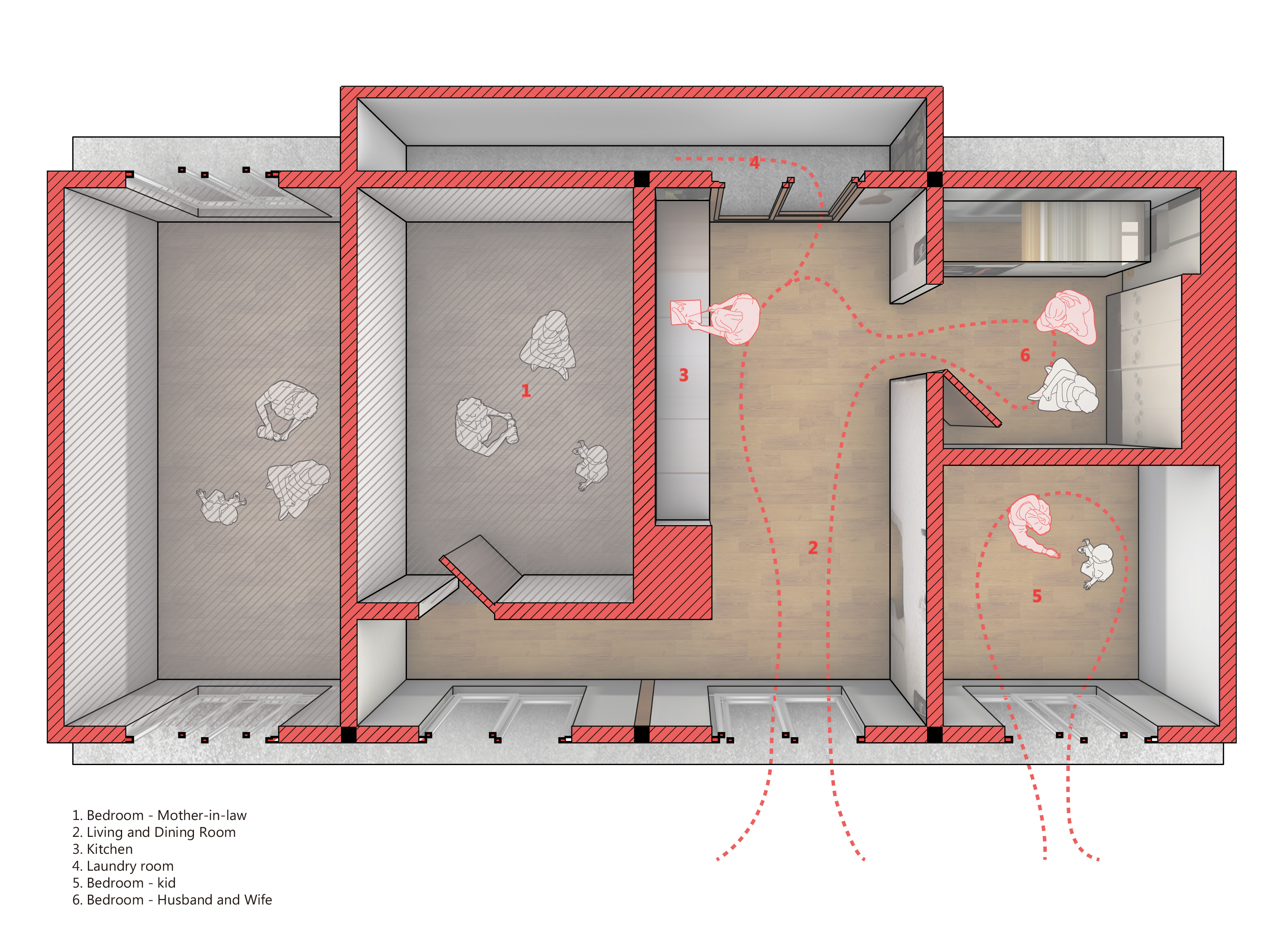

In this section, we are translating the architectural space inhabited by a marriage migrant from Vietnam- Pham, through the images portrayed in the documentary film “Tales of Multicultural Inlaws.” By reconstructing the typical rural house where a marriage migrant lives in Cheongsong, we transform this narrative into a more intimate one. Her hierarchy in the household becomes visible to the viewers- you can see the limited access she has to a lot of the house and her workspace in her living quarters, including the kitchen, living room, and kids’ room. This- clearly shows her unequal position and traditional feminized role in the family.

click here for full screen view of spatial experience

Despite these unfortunate circumstances, more and more individuals have broken this stereotype and become visible in Korean society. In addition, multicultural support centers in communities help integrate new immigrants. Furthermore, policies such as the “Female Marriage Migrant Family Social Integration and Support Policy” and the “Foreigners in Korea Fundamental Treatment Law” help ensure their successful entrance into Korean society.

While these domestic support policies and groups are significant in helping these marriage migrants, the economic benefit these women sent home and the numbers of unmarried men in rural Korea, which remains a phenomenon, means that this marriage migration will not disappear in the short term, and must remain as an ongoing social and cultural concern.

Conclusion

The research exposes the so-called homogeneity of South Korea through the lens of marriage migration at various scales, from the global to the intimate. The story visualizes how urbanization in one country has an impact across the border between countries and permeates everyday life in South Korea—combined with the Confucian culture, which is deeply rooted in rural areas. The urbanization of South Korea has created an unbalanced gender ratio in the rural towns in addition to the more common issues exacerbated by urbanization, such as population decrease and underdevelopment. As a result, female marriage migrants from neighboring countries have been filling up the voids created by urbanization. This phenomenon has caused adverse effects, revealing how South Korea’s so-called homogeneity, a distinct characteristic and pride of the county, is forever transformed.

This research is conducted from the perspective of Korean society, which mainly investigates through the data visualization of population movements. However, if conducted through a political and economy-driven approach, this phenomenon would reveal much more conflict on the scale of international affairs. Therefore, a probable different approach would be to trace back these marriage migrants to their home country by collecting data on their remittance and investigating how this money drives the supply of potential migrants.

Citations

Hye-Kyung Lee, International Marriage and the State in South Korea, Pai Chai University, 2008

Hyunok Lee, Adapting to Marriage Markets: International Marriage Migration from Vietnam to South Korea, University of Toronto Press, 2016

Sending Money Home: Worldwide Remittance Flows to Developing Countries, IFAD Publication, 2006

National Atlas of Korea, Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport, 2019

Hye-Kyung Lee, Problems and Reactions to Marriage Migrants and Their Families, Korean Demographics, 2005

Yugyun Kim et al, Don’t Ask for Fair Treatment? A Gender Analysis of Ethenic Discrimination, Response to Discrimination, and Self-Rated Health among Marriage Migrants in South Korea, Internatilnal Journal for Equity in Health, 2016

Onishi, Norimitsu. “Korean Men Use Brokers to Find Brides in Vietnam.” The New York Times. The New York Times, February 22, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/22/world/asia/22brides.html.

Francis L. K. Hsu, “Confucianism in Comparative Context,” 61.

Lee E, Kim SI, Jung-Choi K, Kong KA (2022) Household decision-making and the mental well-being of marriage-based immigrant women in South Korea. PLOS ONE 17(2): e0263642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263642

Yamanaka, Keiko, and Nicola Piper. 2003. “An Introductory Overview.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal , vol. 12, nos. 1-2, pp

EBS, Documentary Film “Tales of Multicultural Inlaws - The hidden story of a daughter-in-law who is always hungry”, 2015