POWER, POLITICS, AND CONTESTATION IN DHARAVI SLUMS, MUMBAI: A COUNTER-MAP

Investigation

Dharavi, at the heart of Mumbai, India, is at the frontline of oppositional practices confronting neoliberal, futuristic mega-projects focused on capital accumulation, elite consumption, slum clearance, and deregulated real estate speculation.

With accelerating urbanization around the world, cities are witnessing unprecedented demographic and geographical growth. An outcome of unprecedented pressure and advancement is a vision of a global city, thrust upon the urban development, architectural character, and identity of cities. Urban centers thus remain no more a static entity but a ground for power struggle for coexistence and legitimization of collective identity by multiple stakeholders. Common property is acknowledged as a commodity of multiple claims and contestation by its residents against hegemonic power. Dharavi’s development, or rather un-development, reflects a larger play of governmental authority and convergence of rules and policies, which frequently mask the existence of any informal quarters. Do the law and the city work in tandem to protect the city’s most vulnerable residents? An in-depth inquiry is conducted along with an analysis of the informal-urban, projecting spatio-political defenses, offenses, and alliances that define the future of these contested slum-landscapes throughout Mumbai. A contestation of over-debates, worn out bidding processes, compromised on-ground representation, and overworked proposals. Using a counter map, we identify potential datasets and map the scales and scalability of various neo-liberal redevelopment processes initiated by political will and their outcomes.

The Team

ERYN HALVEY, Urban Planning & Real Estate Development, Columbia University, GSAPP

PRADITI SINGH, Urban Design, Columbia University, GSAPP

SURABHI DAHIVALKAR, Urban Design, Columbia University, GSAPP

ARCH A4890: Conflict Urbanism: 2022: LAURA KURGAN, Professor of Architecture, ADAM VOSBURGH, Graduate TA.

Research Methodology

Inspired by Vyjayanthi V. Rao’s work on Beneath the Tent of a Horizonless Sky in Spring ’22, we conducted an independent investigation on the infra-politics of Mumbai and how hegemonic power systems have shaped Dharavi until now. Using elements of Counter Mapping we indulged in: Referenced + Public-Sourced Fieldwork, Video Analysis, Building an Image-based data Complex, and Investigative Journalism All combined as a tool for open source investigation to identify the irregularities in the power, economic and spatial structure that shapes Dharavi as an urban fabric today, as well as voids in the process. Investigating and tracing politics and policies restricting housing supply in Mumbai. Tracing the decisions of slum demolition, upgradation, rehabilitation, and redevelopment programs parallel to policy change devised by the state and SRA (Slum Rehabilitation Authority) and the compounding effects on Dharavi.

Abbreviations & Definitions to Position the Reader

SRA: Slum Rehabilitation Authority

DRP: Dharavi Redevelopment Project

SRS: Slum Rehabilitation Scheme

PMAY: Pradhan Mantri Aawas Yojana (A presidential scheme for poverty alleviation)

BMC: Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation

SPA: Special Planning Authority

MMPC: MM Project Consultants, DRP ARchitect

SecLink: Current Bid Winner (2019)

Adani: Competing Bid (2019)

The Site

The Dharavi slum in Mumbai is a sprawling 525‐acre mosaic of matchbox houses with rickety roofs and questionable sanitation housing over one million residents in the center of India’s glitzy financial capital of Mumbai. Dharavi’s residents. ( Simon Crerar, “Mumbai slum tours: Why you should see Dharavi”, The Times, May 13, 2010)

Its prime real estate value is defined by its land mass sprawling across 0.81 sq. miles, its proximity to four busy local railway stations: Bandra, Mahim, Matunga, and Sion, and proximity to the airport. All shaping the fabric for the future 5-minute infrastructure models.

A gold mine for advanced capitalistic systems, it has a strategic advantage in leveraging Dharavi improvement costs with high saleable regions. In its 18 years of upgradation plan, Large-scale rehabilitation models have been approved and designed to provide profit margins for builders and political parties, however, the projects are inevitably entangled in the political battle.

Disparity Mapped

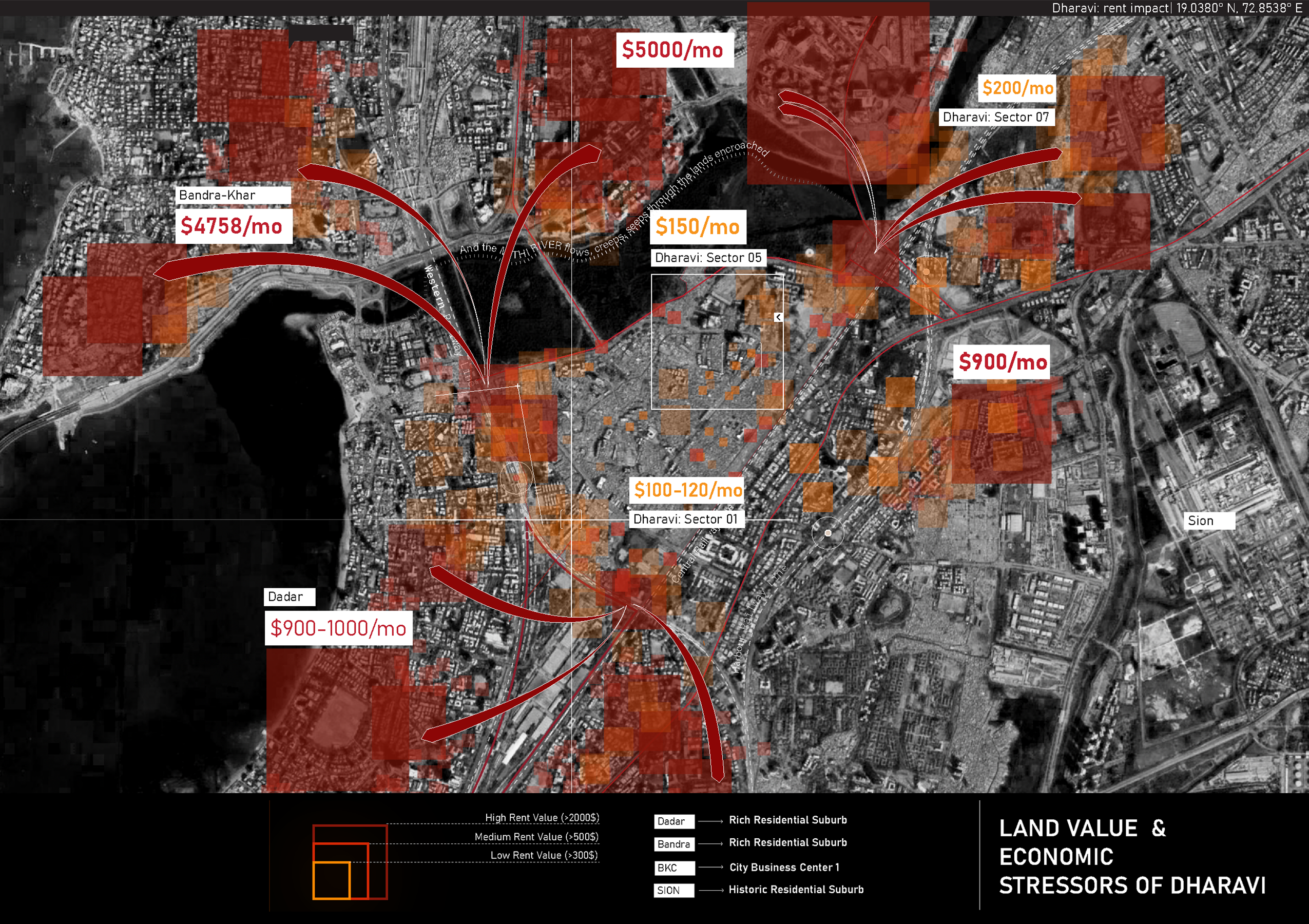

Image 01: Google sourced imagery illustrated. This work is a derivative of Sanctioned Proposed Land use Plan of Dharavi by the Government of Maharashtra SRA-DRP and MMPC.

Image 01: Google sourced imagery illustrated. This work is a derivative of Sanctioned Proposed Land use Plan of Dharavi by the Government of Maharashtra SRA-DRP and MMPC.

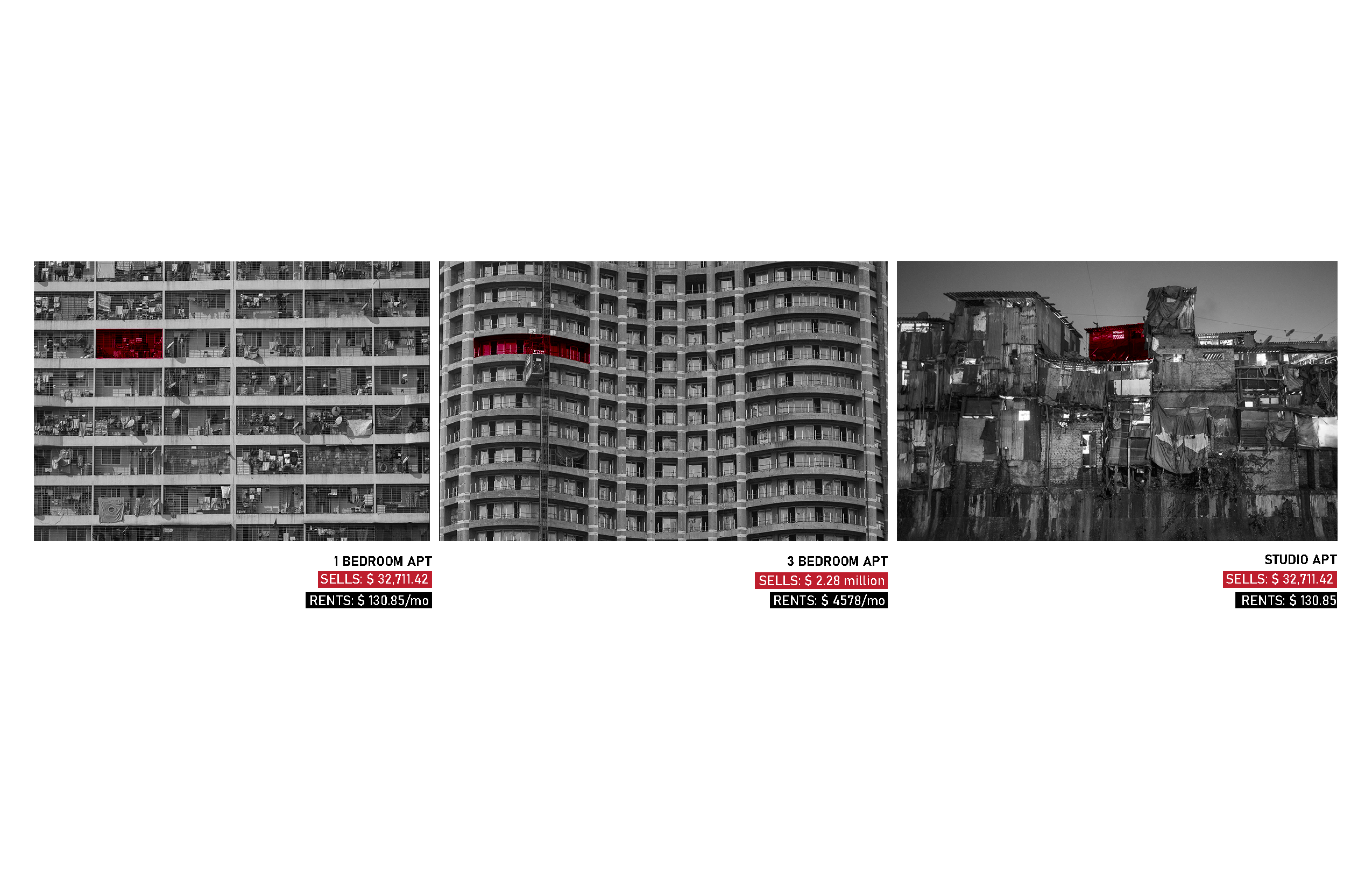

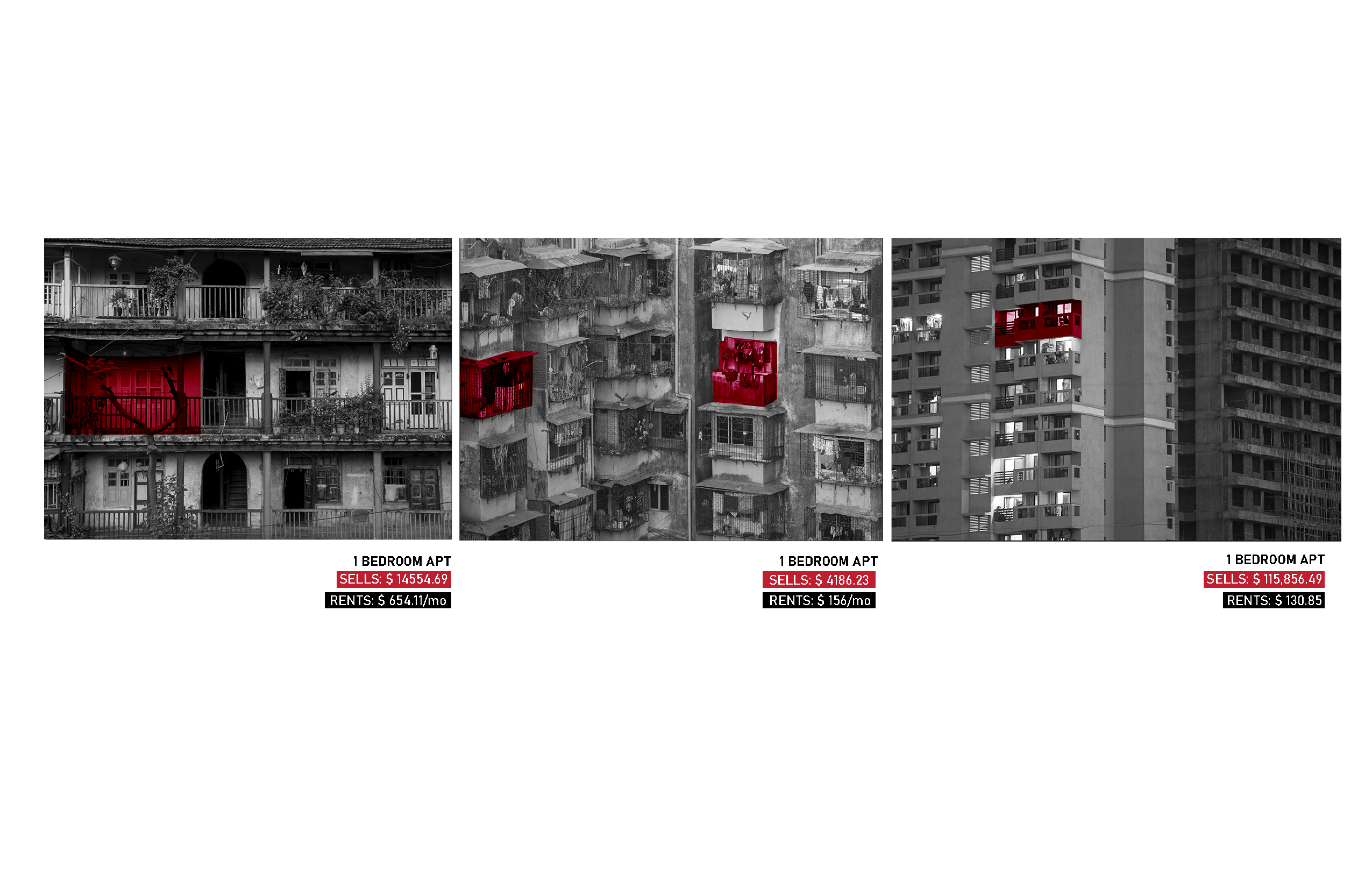

Image 02: From shanky to swanky; Mapping on google sourced map with Danish Siddiqui’s photographs for The Guardian , April 2015/ Desaturated from original.

Image 02: From shanky to swanky; Mapping on google sourced map with Danish Siddiqui’s photographs for The Guardian , April 2015/ Desaturated from original.

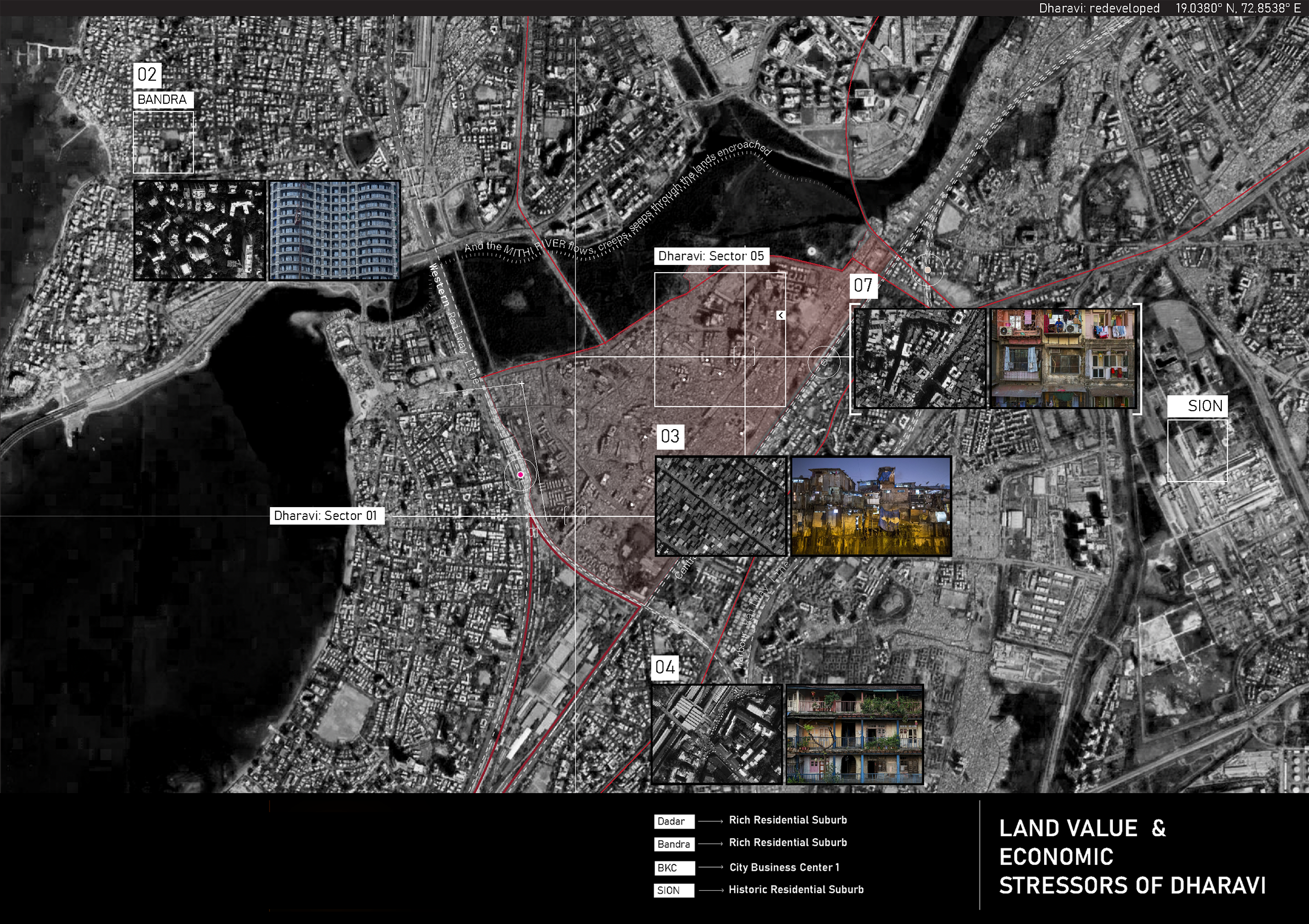

Image 03: From shanky to swanky; Mapping stresses of adjacent neighborhoods with richer land value and higher rents on Dharavi

Image 03: From shanky to swanky; Mapping stresses of adjacent neighborhoods with richer land value and higher rents on Dharavi

Image 04: From shanky to swanky; This work is a derivative of Danish Siddiqui’s photographs for The Guardian, April 2015/ Saturated from original

Image 04: From shanky to swanky; This work is a derivative of Danish Siddiqui’s photographs for The Guardian, April 2015/ Saturated from original

A dataset was curated out of listed rates of units from a local website: 99acres.com. The resulting sampling is bicubically interpolated from 20-30 rates per identified region, based on availability. The remainder is corroborated by the journalistic research.

Past Efforts

Through its lifespan, Dharavi and its people have witnessed multiple projects, researches indulged with on its behalf. Multiple firms and companies across the globe have participated in the redevelopment process of Dharavi either by attempting through a competition or proposing schemes and policies. The shortlisted tender awarded projects by Seclink and MM Project consultants still remain entangled within the hierarchical structure of government bodies overlooking the redevelopment process. This failed system can be viewed forensically through the lens of undeveloped projects.

Image 05 & 06: Official Dharavi Redevelopment Project Plan : Source: MM Project Consultants, Seclink Dubai overlaid on Google Sourced Imagery and timeline of project revisions

Image 05 & 06: Official Dharavi Redevelopment Project Plan : Source: MM Project Consultants, Seclink Dubai overlaid on Google Sourced Imagery and timeline of project revisions

Image 07-10: The best idea to redevelop Dharavi slum? Scrap the plans and start again; This work is a derivative of digital productions from participating firms-2008 Reinventing Dharavi competition (as listed), sourced from The Guardian, overlaid on Google Sourced Imagery

Image 07-10: The best idea to redevelop Dharavi slum? Scrap the plans and start again; This work is a derivative of digital productions from participating firms-2008 Reinventing Dharavi competition (as listed), sourced from The Guardian, overlaid on Google Sourced Imagery

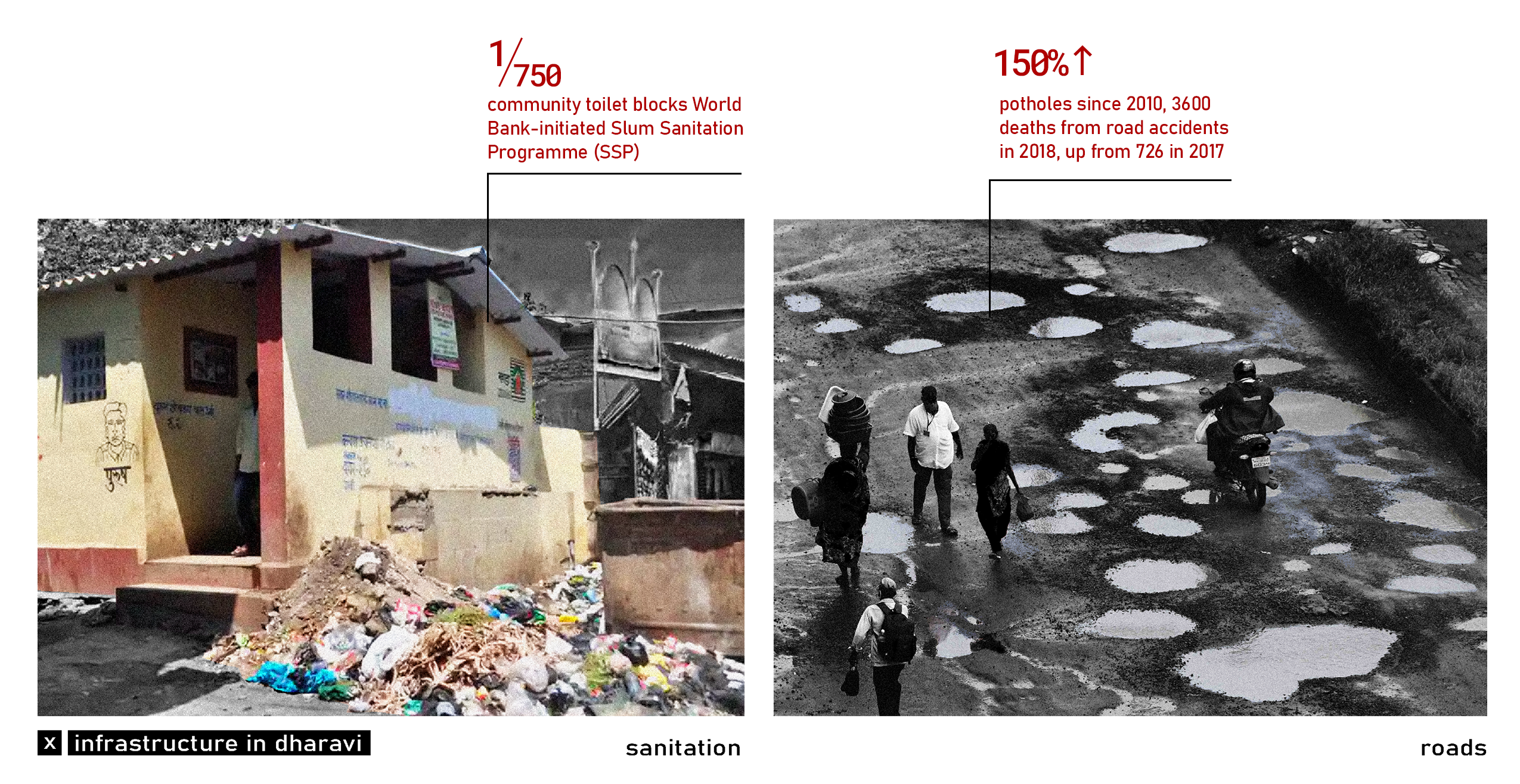

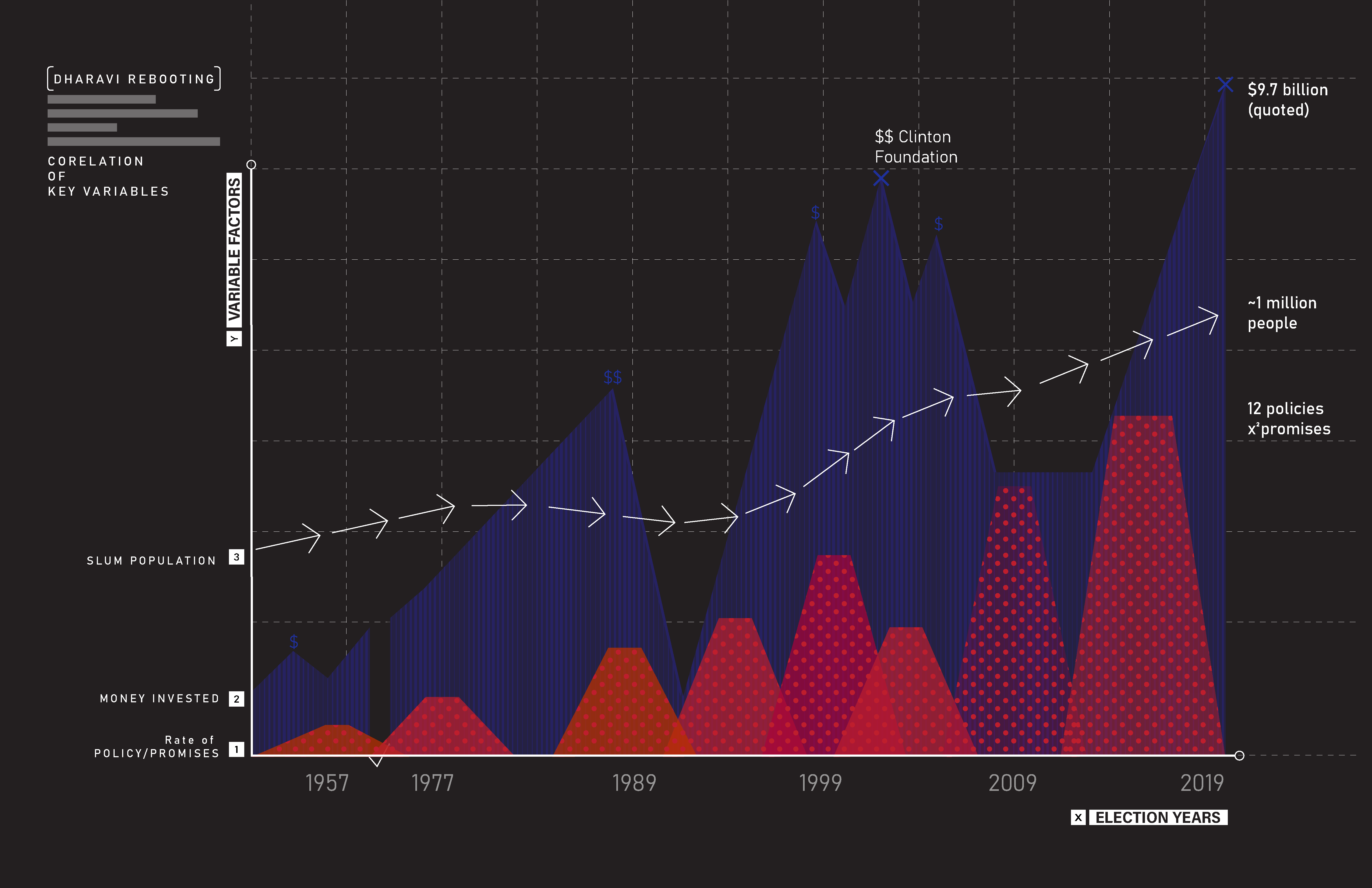

Money Influx + Infrastructure Development

The past 50 years have seen a noticeable influx of money for the redevelopment or upgradation of Dharavi. We cross-referenced the infrastructural developments and investments during this time period along with the journalistic reports from 2000s-2020s. It was discovered that the foundation funds/ investments were not synonymous with the outcomes on the ground. It is conjectured that channels of black economy/ hidden economy underline the development projects.

Image 11

Image 11

The first investigation studied the development of 3x 4 lane roads along with the territory, and the upgradation of abutting roads (namely, 100ft, and 90ft roads). This has increased the vehicular circulation in the area by 45% since 2015. Parallel developments include the construction of link roads from other parts of the city to Dharavi.

Image 12

Image 12

The second and third investigations follow the multi-track railway stations and tunneled metro developments along the edge. These are mapped against undeveloped edges of the slums. Disparity and wealth influence is evident, while these projects employ cheap labor force from the slum pockets. Parallelly, the internal slum infrastructure -sanitation, and pedestrian bridges are repeatedly observed to be in substandard conditions.

Image 13

Image 13

A noticeable conflict is recorded through an image complex of sanitation infrastructure and toilet blocks constructed under the World Bank-initiated Slum Sanitation Programme (SSP) since 2001. This was aided by Rahul Mehrotra’s research on Public Sanitation infrastructure for SPARC (a local

NGO). Nearly half-a-million residents of the “notified” slums are served by these 750-odd communities. A simple calculation reveals that most of the SSP toilet blocks thus have one toilet seat for 190 users, as against the city municipality’s -accepted WHO norms of one toilet per 50 people.

Additionally, the internal roads when constructed or repaired are of substandard material, resulting in frequent damage during the annual monsoons/rains.

Image 14

Image 14

Image 11-14: All maps are Google Sourced imagery, overlaid with Bhuvan NSRC Open Data; desaturated from original

GIF: Variable Sources of images

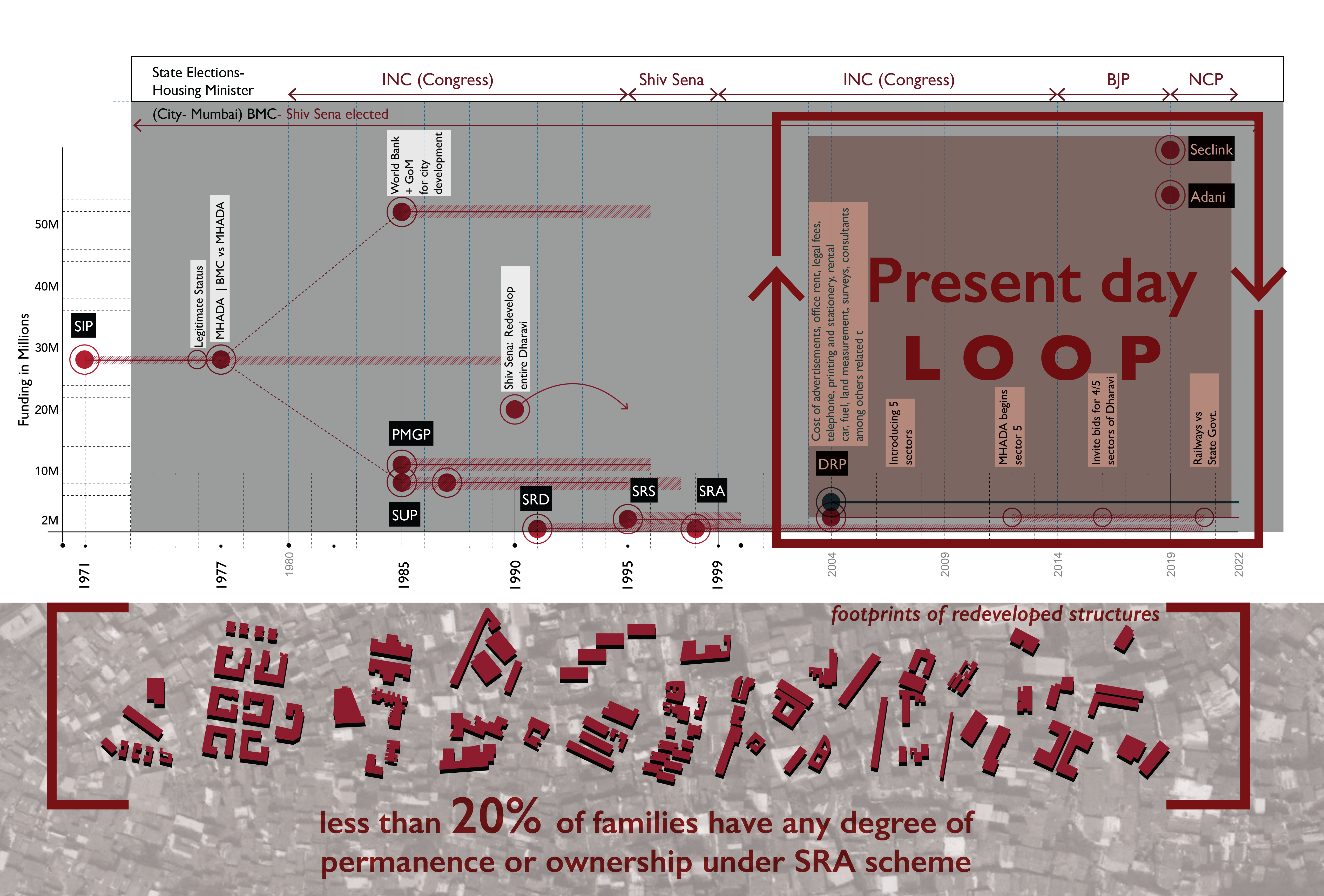

Process of Redevelopment

An (un)lawful mapping of the process indicates the multiple loops in a rather straightforward/ constitutionally bound process. The official and unofficial structures of the system underlie the redevelopment process.

A general perception of Dharavi is either the shanty structures, with corrugated iron sheets or teeming industrial workers, smiling faces in the home based industries. We would like to acknowledge that these pictures are more often misleading, and asserting to unlawful actions on ground; including asserting to the loops charted in this process.

The informal economy in Dharavi has repeatedly proven to be a source of informal investments for several NGOs, political representatives (voter banks). Vested interests of every party, compounds this loop by at least twice.

Image 15: This work is an adaptation of the processes listed Slum rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai

Image 15: This work is an adaptation of the processes listed Slum rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai

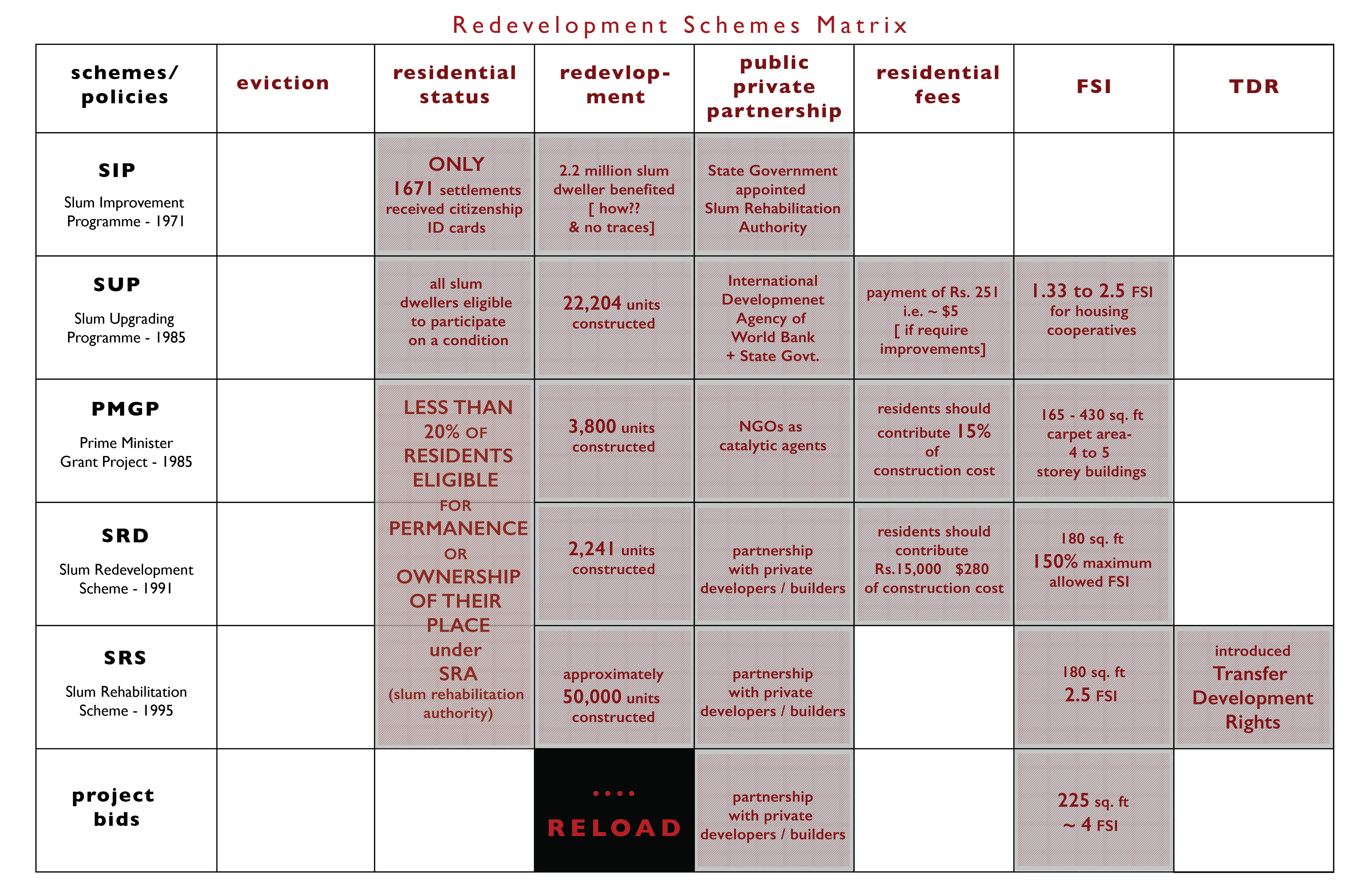

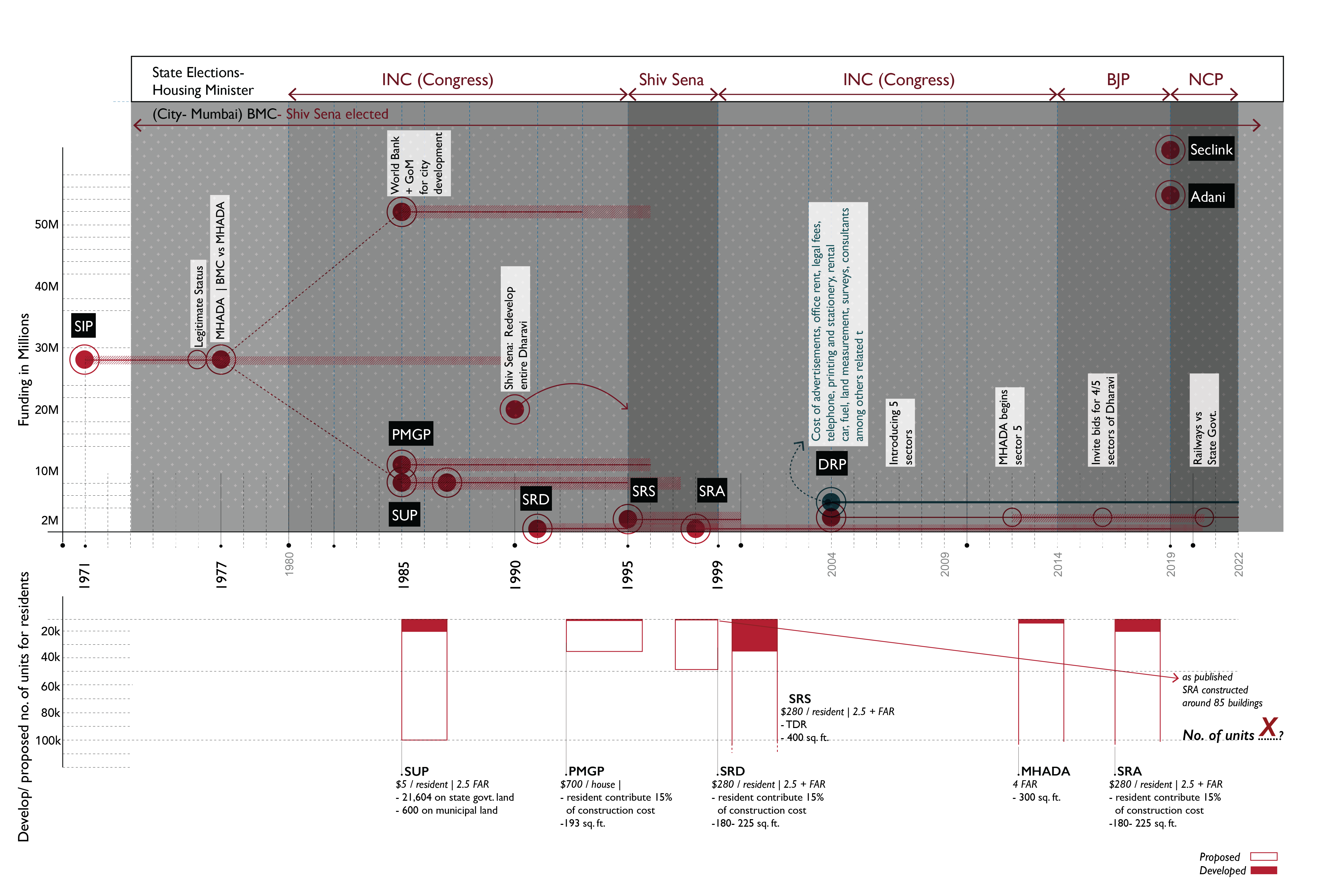

Public Schemes/ Policies

How to map benefitted residents in an unreliably mapped area with non-existing geographically allocated data which is impossible to pin-point in a complex, dynamic area like Dharavi

Using the process of investigative journalism and fieldwork, we extensively studied the mechanism and structure of each scheme converging with political decisions and acts. Each quantitative figure is extracted from press journals and published articles that do not have a basis of geographical location within the context of Dharavi or a method of verifying it with ground reality. Relying on comparatively trustable sources, we observed that within the workability of these schemes, the framework is plagued by the play of partnership between the stakeholders and the policy dictators.

The rise of slums in post-colonial Mumbai experienced an experimentation of schemes and policies in the name of Redevelopment projects for Dharavi. This timeline of the redevelopment process marks the limitations of each scheme as each scheme is proposed more because of a political agenda and less to do with improving critical conditions of the area. Initially, schemes were proposed without conducting a thorough survey of Dharavi and what makeshift improvements are required in each corner. A less popular belief that Dharavi is more complex than the generalized solutions and policies proposed overall, plagued the redevelopment process and gave rise to unsuccessful schemes consecutively, one after the other.

Image 16: Limitations and Failures of the schemes that restructure Dharavi.

This matrix highlights the contributions of each scheme and the real beneficiaries of the uninterrupted cycle of parent policy developers and recipient private builders that inherit the outcome. A composite score of social factors and vulnerability is being neglected here.

The Slum Improvement Programme by the State government promised to protect the residents from eviction and published a figure of 2.2 million slum dwellers to be benefited from the scheme. There is a lack of ground figures about who these residents are and where they were located. In parallel, an observation has been made that the scheme was more focused on the improvement of infrastructure. While introducing SRA (Slum Rehabilitation Authority implemented for the execution of the improvement scheme) only a few selected residents of Dharavi are eligible for permanent residency.

With the start of the Slum Upgrading Programme, an internal conflict developed among the residents who were and weren’t in a position to pay for the construction cost. In spite of the State Government being in a partnership with the International Development Agency of World Bank, this scheme restricted the places of upgradation due to unsettled boundaries between each slum and their respective cooperatives which defined the eligibility criteria to participate in SUP. The inefficiency of the program and unclear surveys resulted in the construction of only 22,204 units in total.

Image 16: Limitations and Failures of the schemes that restructure Dharavi.

This matrix highlights the contributions of each scheme and the real beneficiaries of the uninterrupted cycle of parent policy developers and recipient private builders that inherit the outcome. A composite score of social factors and vulnerability is being neglected here.

The Slum Improvement Programme by the State government promised to protect the residents from eviction and published a figure of 2.2 million slum dwellers to be benefited from the scheme. There is a lack of ground figures about who these residents are and where they were located. In parallel, an observation has been made that the scheme was more focused on the improvement of infrastructure. While introducing SRA (Slum Rehabilitation Authority implemented for the execution of the improvement scheme) only a few selected residents of Dharavi are eligible for permanent residency.

With the start of the Slum Upgrading Programme, an internal conflict developed among the residents who were and weren’t in a position to pay for the construction cost. In spite of the State Government being in a partnership with the International Development Agency of World Bank, this scheme restricted the places of upgradation due to unsettled boundaries between each slum and their respective cooperatives which defined the eligibility criteria to participate in SUP. The inefficiency of the program and unclear surveys resulted in the construction of only 22,204 units in total.

The ending period of schemes introduced till 1985 is when the improvement and up-gradation ideas for slums were transformed into real estate development as the private sectors got attracted to slums. In time, the only growth observed from the matrix is the Floor Space Index (FSI) or FAR (Floor Area Ratio) and the increase in construction cost for accommodating larger areas. To this day, the unclear power systems, the clash between public-private partnerships, and proposed unrealistic modules and policies have stripped residents of Dharavi of their comfortable life.

Stakeholders + Relationships

Image 17

Image 17

Image 18

Image 18

A list of campaign agendas/ promises and policies are charted against key election periods of the state, along with the recorded monetary funds (key : funds from global foundations like World Bank and Seclink-now). The outcome of projects are incoherent with the population growth (influx of migrants) and political campaign promises.

Politics of Care

How to map politically influenced decisions that do not disclose the failure of schemes and policies officially

Through the process of locating Dharavi related specific promises that were vocally made in order to win the political elections and analytically examining election inspired incidents within the elaborate timeline of the schemes, we identified changes made in the framework of the redevelopment process.

Image 19: Conflict between the state and the local (city) elected bodies and the contrast of proposed v/s constructed residential units.

The City of Mumbai is located in the state of Maharashtra. The two main electoral bodies that look over the redevelopment process of Dharavi slums are 1) The State government and 2) the local body (city council) Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), the governing civic body of Mumbai. Shiv Sena (a right- wing Marathi regionalist and Hindu ultra nationalist political party) has been a constant BMC (locally) elected body. Whereas, the State elected housing ministers have been from different political parties from the year 1980 till today.

For the execution of Slum Improvement Scheme (SIP), the state government appointed SRA ( Slum Rehabilitation Authority) in 1971 and established MHADA (Maharashtra Housing and Areas Development Authority) in 1977. A conflict of land ownership between private, municipal and state owned land, limited the provision of facilities of the schemes. Dharavi, a gold mine, became a political battleground as both the elected bodies disfavored losing authority over future development of the area. This political war between the local body and state body continued in the next upcoming scheme of SUP (Slum Upgrading Programme) as well. With the lack of legal tenure to housing of residents, the dispute of reclaiming private land either by BMC or MHADA resisted the upgradation process of slums. The Prime Minister Grant Project (PMGP) was established to flip this political battle. To overcome this, BMC elected body Shiv Sena declared that if they won the state elections they would redevelop the entire city’s slums for free (free of construction cost charged to the residents of the slums). As Shiv Sena won the state elections, they cautiously replaced Slum Redevelopment Scheme (SRD) to Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS) just to symbolize their dominance over the earlier political party. In the act of adhering to the promise they vocally made, out of 4 million residential units, only 50,000 were constructed.

SRA continued the process of redevelopment while the Dharavi Redevelopment Plan (DRP) took off with division of the area into 5 sectors. Almost double of the project estimated cost was spent in the mechanism and management of the process and not on the construction of the residential units. MHADA gained the authority to develop sector 5 along the historical political dispute, while the other sectors invited bids. Even today, the conflict over the ownership, transfer of power and economic beneficial structure demand is seen between the Central Railways and the State Government.

Image 19: Conflict between the state and the local (city) elected bodies and the contrast of proposed v/s constructed residential units.

The City of Mumbai is located in the state of Maharashtra. The two main electoral bodies that look over the redevelopment process of Dharavi slums are 1) The State government and 2) the local body (city council) Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), the governing civic body of Mumbai. Shiv Sena (a right- wing Marathi regionalist and Hindu ultra nationalist political party) has been a constant BMC (locally) elected body. Whereas, the State elected housing ministers have been from different political parties from the year 1980 till today.

For the execution of Slum Improvement Scheme (SIP), the state government appointed SRA ( Slum Rehabilitation Authority) in 1971 and established MHADA (Maharashtra Housing and Areas Development Authority) in 1977. A conflict of land ownership between private, municipal and state owned land, limited the provision of facilities of the schemes. Dharavi, a gold mine, became a political battleground as both the elected bodies disfavored losing authority over future development of the area. This political war between the local body and state body continued in the next upcoming scheme of SUP (Slum Upgrading Programme) as well. With the lack of legal tenure to housing of residents, the dispute of reclaiming private land either by BMC or MHADA resisted the upgradation process of slums. The Prime Minister Grant Project (PMGP) was established to flip this political battle. To overcome this, BMC elected body Shiv Sena declared that if they won the state elections they would redevelop the entire city’s slums for free (free of construction cost charged to the residents of the slums). As Shiv Sena won the state elections, they cautiously replaced Slum Redevelopment Scheme (SRD) to Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS) just to symbolize their dominance over the earlier political party. In the act of adhering to the promise they vocally made, out of 4 million residential units, only 50,000 were constructed.

SRA continued the process of redevelopment while the Dharavi Redevelopment Plan (DRP) took off with division of the area into 5 sectors. Almost double of the project estimated cost was spent in the mechanism and management of the process and not on the construction of the residential units. MHADA gained the authority to develop sector 5 along the historical political dispute, while the other sectors invited bids. Even today, the conflict over the ownership, transfer of power and economic beneficial structure demand is seen between the Central Railways and the State Government.

Image 20: The contrast of proposed v/s constructed residential units and the unending loop.

Image 20: The contrast of proposed v/s constructed residential units and the unending loop.

Since the redevelopment of Dharavi is affected by the political war and entangled ownership structure, the top bidders, UAE based Seclink Technologies Corporation and Adani Infra that were shortlisted earlier would go through the entire tendering process again. Even though few published articles mention the call for new tenders, others mention dissolution of existing GR (Government Resolution) of DRP.

GIS (Not So) Open Source Data

Image 21: GIS mapping launched by SRA inaccessible to extract data.

Image 21: GIS mapping launched by SRA inaccessible to extract data.

As the app shows availability of GIS data as a means of communication and an act of showing transparency in the system, the esri India - ‘GIS based slum information management system’ mentions the availability of the data only for the concerned department of Mumbai Metropolitan Region for their planning purpose. This tool is developed for speedily implementation of SRA schemes, without providing a direct communicating tool for the residents.

Image 22: GIS mapping launched by SRA mapped only the ground floor structures.

Image 22: GIS mapping launched by SRA mapped only the ground floor structures.

There is lack of clarity with respect to full documentation of the residents on site.

Conclusion

Infrapolitics are used by both the powerful and the powerless, by governments, corporations, citizens’ associations, or individuals, as acts of oppression, dispossession, exclusion, protest, or resistance. (Infrapolitics seminar, Center for spatial research). Today public infrastructure and rehabilitation buildings are manifestations of the broken contract between the state and its most vulnerable citizens.

One slum. Four layers. Four realities.

On the ground floor is a hardship of bleating traffic and substandard constructions. One floor up is work, trade and commerce that crosses global boundaries Another floor up is politics. And at the top is hope.

“Dharavi,” said Hariram Tanwar, 64, a local businessman, “is a mini-India.”

What Lies Ahead of Us?

Image 23: illustrated conflict between responsible project partners

Image 23: illustrated conflict between responsible project partners

It is impossible to ignore the continuous conflicts between dominant power structures and on- the - ground actions after more than 50 years of slum reforms and policies have molded the Indian urban rural fabric. Today, the nature of Public- Private Partnership (PPP) generates profile- based credits in TDR (Transferable Development Rights) which ensures a substandard living versus developer profits. What is now needed is not just more than participatory planning systems, but a pivotal shift in designing PPP models.

What if the PPP models are redefined as equity incentivized with social development/advancement credits?

All in pursuit of ushering a future rooted in realization of human rights, social equity and resilience.

Image 24: Curating datasets for permeable landscapes & fluid economies

Image 24: Curating datasets for permeable landscapes & fluid economies

Given these considerations, we intend to push the boundaries of creating datasets. And ask: How can we curate datasets for a permeable landscape and fluid economics?

How might these datasets aid in shaping the future of these spaces as they exist, evolve, and transition from one to the next?

Citations

“About DRP : Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA).” Accessed May 7, 2022. https://sra.gov.in/page/innerpage/about-drp.php.

“Beneath the Tent of a Horizonless Sky - Architecture - e-Flux.” Accessed March 1, 2022. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/conditions/296455/beneath-the-tent-of-a-horizonless-sky/.

“Dharavi Development Project Stuck as Railway Land Is yet to Be Transferred to State: Maha CM – ThePrint.” Accessed May 7, 2022. https://theprint.in/india/dharavi-development-project-stuck-as-railway-land-is-yet-to-be-transferred-to-state-maha-cm/887094/.

Dhikle, Sanjay, and Rakesh Lakhena. “GIS Based Slum Information Management System.” ESRI India, n.d. https://www.esri.in/~/media/esri-india/files/pdfs/events/2017/indiauc/papers/UCP021-gis-based-slum-information-management-system.pdf.

Free Press Journal. “Mumbai: Rs 31.27 Crore Spent on Dharavi Redevelopment Project Related Works over 15 Years, Reveals RTI Reply.” Accessed May 7, 2022. https://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/mumbai-3127-crore-spent-on-dharavi-redevelopment-project-related-works-over-15-years-rti.

Kolokotroni, Martha. “THE POLITICS OF DHARAVI: On the Relation between Discourse and Territorial Production,” 2015. https://center4affordablehousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/India-The-Politics-of-Dharavi-On-the-Relation-between-Discourse-and-Territorial-Martha-Kolokotroni.pdf.

“Mere 100 Families Own Dharavi Slum Sprawl: Survey” Accessed May 7, 2022. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/ampnbspmere-100-families-own-dharavi-slum-sprawl-surveyampnbspampnbspampnbsp/articleshow/11138221.cms.

“Poor Sanitation in Mumbai’s Slums Is Compounding the Covid19 Threat | ORF.” Accessed May 7, 2022. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/poor-sanitation-in-mumbais-slums-is-compounding-the-covid-19-threat-66216/.