Amazon: A Question of Distribution

Data source: MWPVL, Good Jobs First & California Open Data Portal

Data source: MWPVL, Good Jobs First & California Open Data Portal

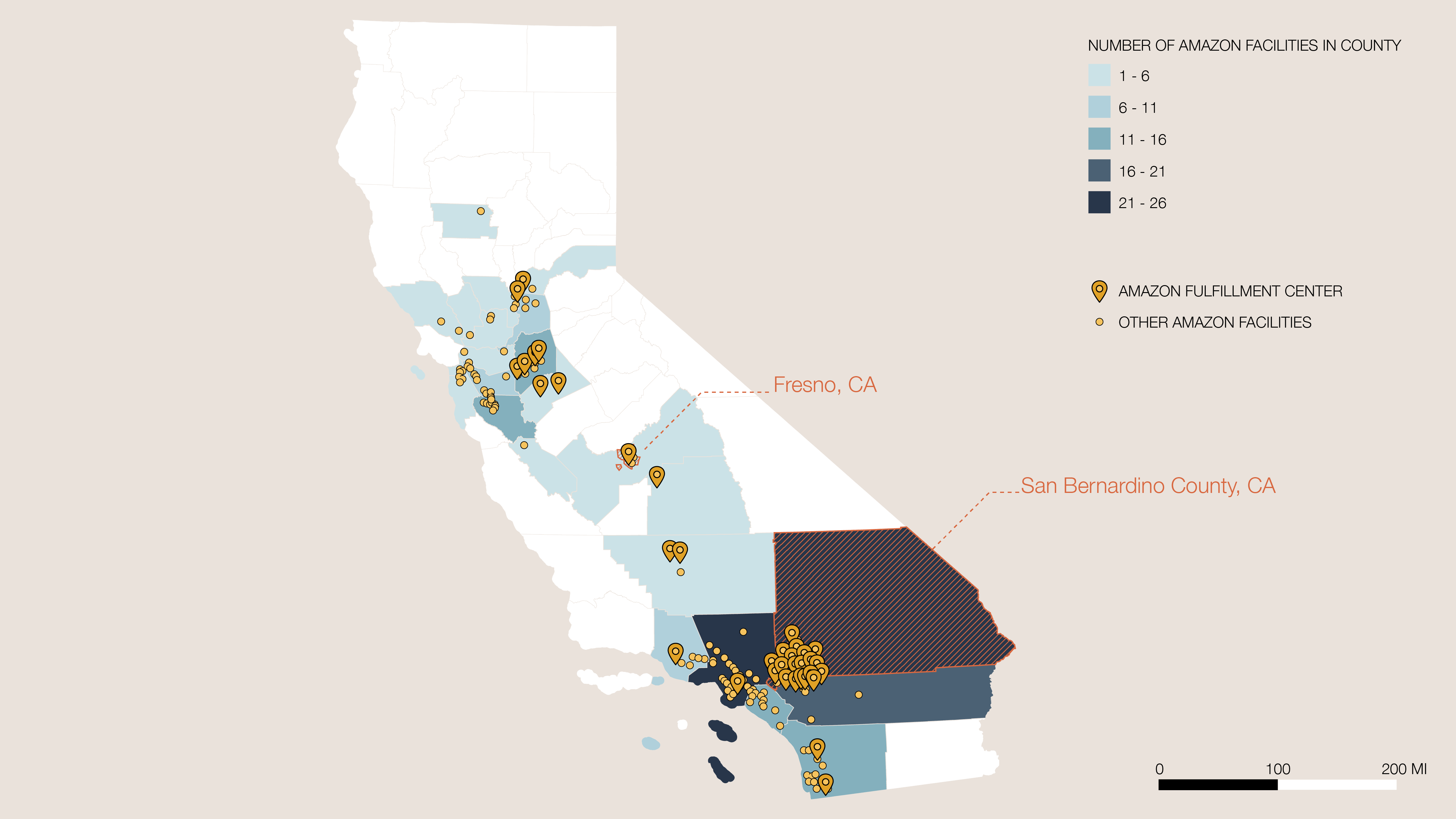

The state of California boasts the highest number of Amazon facilities across the US—and that number is continually growing. The COVID-19 pandemic and related stay-at-home orders have increased the demand within the online marketplace, contributing to an exponential growth of Amazon’s distribution networks in just the last few years.

These facilities are heavily entangled in the state’s economic structure, playing large roles in its employment rate, subsidies, sales taxes, and so on. Of these, sales taxes—more specifically, the Bradley-Burns 1% Local Sales and Use Tax (henceforth Bradley-Burns Tax)—and its distribution has been a subject of increasing contention between the cities who host Amazon fulfillment centers (host cities) and cities that don’t (non-host, or “consumer” cities), over who gets how much of the revenues generated from Amazon sales tax. What is the Bradley-Burns Tax, and why has it created so much tension between host cities and non-host cities? Furthermore, what socioeconomic and environmental conflicts at the inter-city and intra-city scales lie beyond the simple dollar amounts of the tax revenue?

The following study is divided into three sections. First, we introduce the mechanics of the conflict between the cities over Bradley-Burns Tax, and the claims made by the cities with regards to the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of the Amazon fulfillment centers. Secondly, we test these claims made at the inter-city scale by examining the socioeconomic makeup and pollution rates in the densely populated cities in San Bernardino county. We then move onto the third section in which we examine the same metrics but in a relatively isolated city of Fresno,1 in order to more closely examine some of the consequences of Amazon fulfillment centers within the city limits. Finally, after analyzing the various sources of conflicts between the cities, and between the communities within cities, we draw overall conclusions on the consequences of hosting Amazon fulfillment centers for these communities.

California Sales Taxes and Jurisdictions: Bradley-Burns 1% Local Sales and Use Tax

Data source: California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

Data source: California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

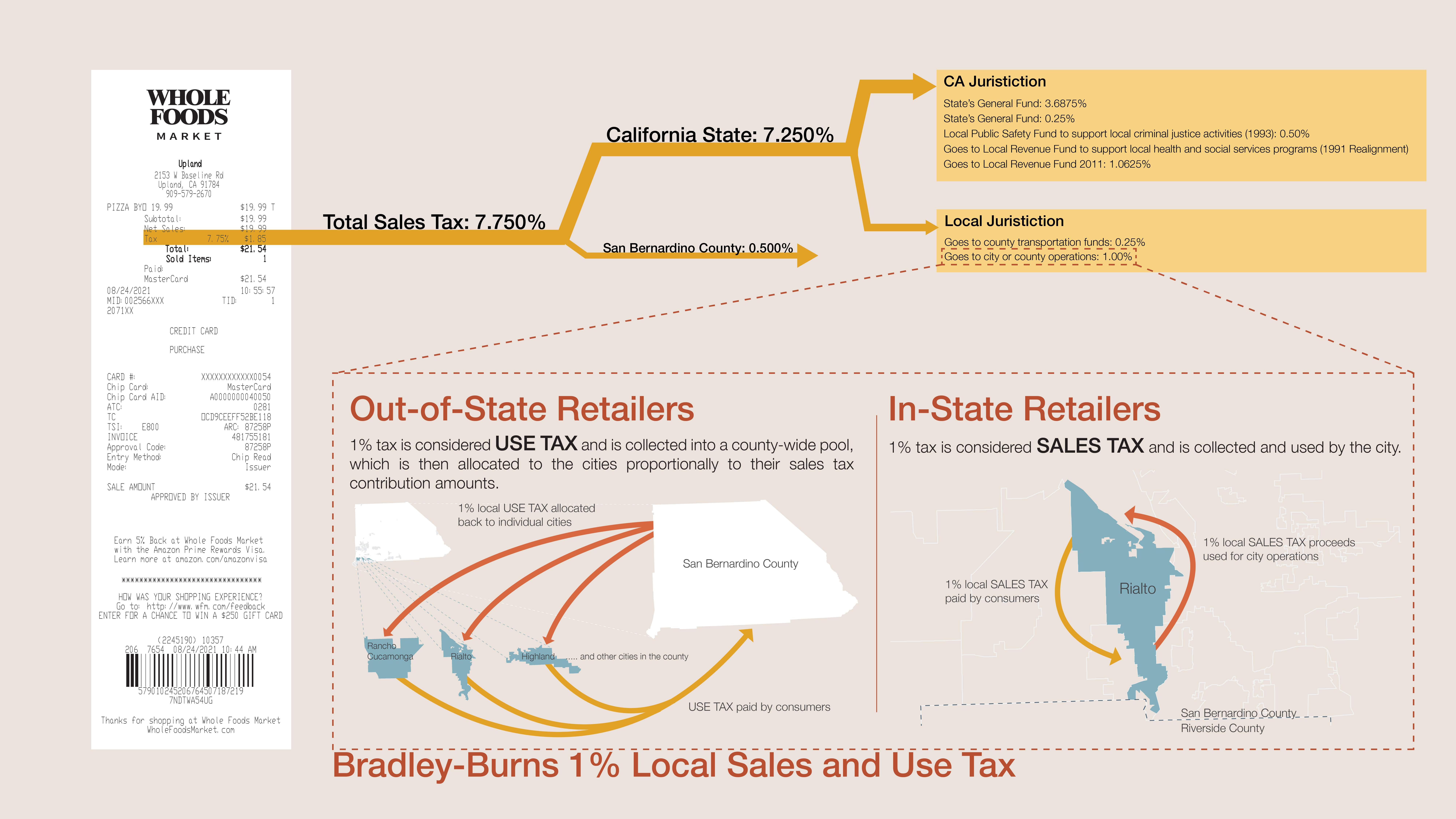

In order to more fully understand the source of this conflict, we begin by understanding the ways in which sales tax works in California. Every city in the state of California is subjected to a statewide sales tax rate of 7.25% plus the local tax that is added at the county level, the city level, or both. For example, a consumer buying pizza at a Whole Foods store in Upland, CA, a city in San Bernardino county, is charged a total of 7.75% in sales tax, 7.25% of which is mandated by the state, and 0.5% of which is mandated by the county. Not all of the 7.25% sales tax goes to the state, however. The Bradley-Burns 1% Local Sales and Use Tax (henceforth referred to as the Bradley-Burns tax) is a statewide tax whose revenues are actually under the local jurisdiction: either the city or the county of where the sale occurs (“place of sale”).

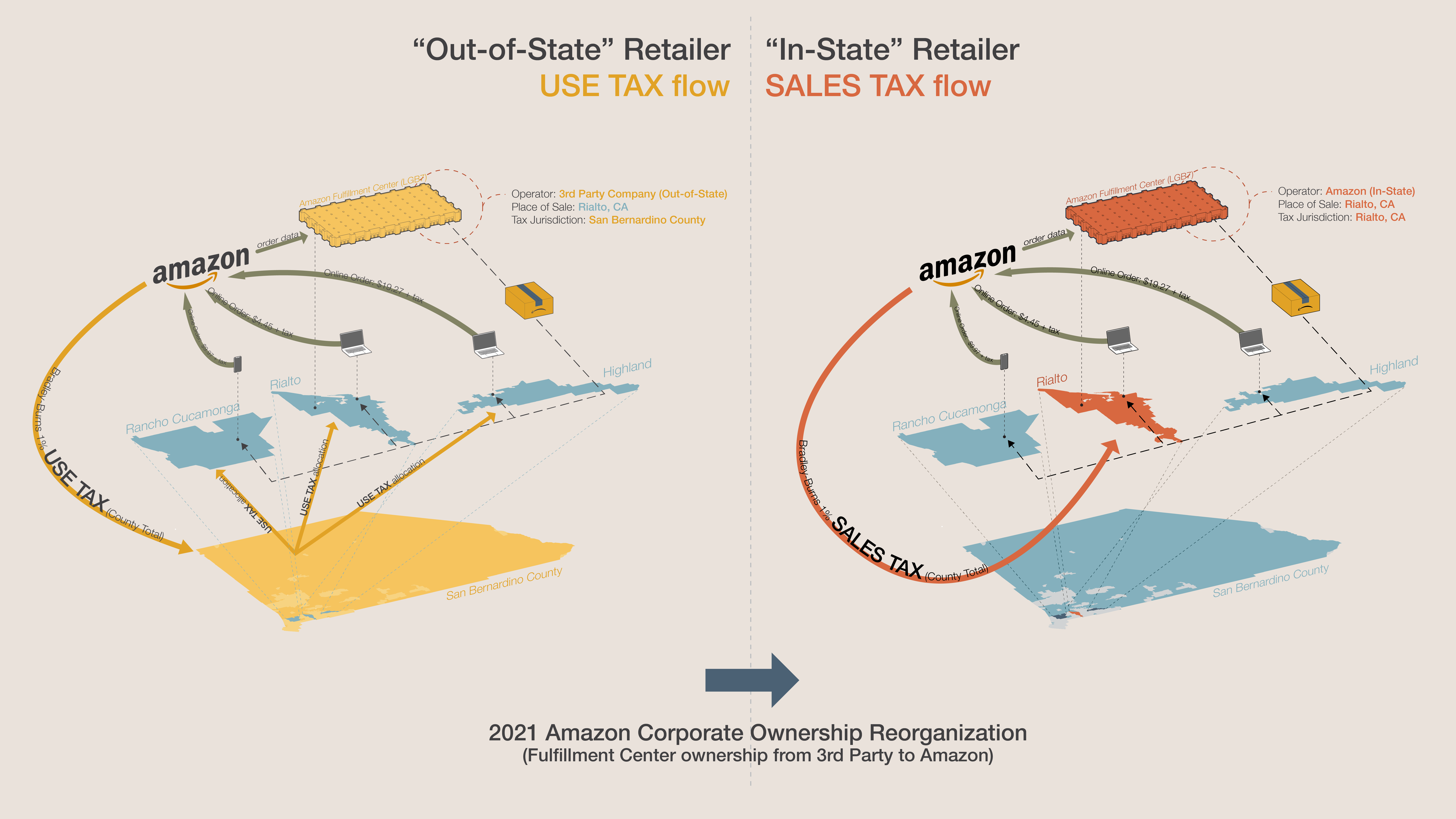

The Bradley-Burns tax is divided into two categories, depending on whether the retailer is considered in-state or out-of-state. If the retailer is considered “in-state” under California law, the tax is considered a sales tax, and its jurisdiction belongs to the city in which the sale occurred (e.g. you go to a local bakery, and the 1% of the tax collected for the pastries you purchased is considered sales tax, and it will belong to the city). However, if the retailer is considered “out-of-state,” the tax is actually considered a use tax, and the taxes that are collected in each city within the county are pooled together at the county level, and reallocated among all of the cities in that county—whether they had any use tax revenues or not.

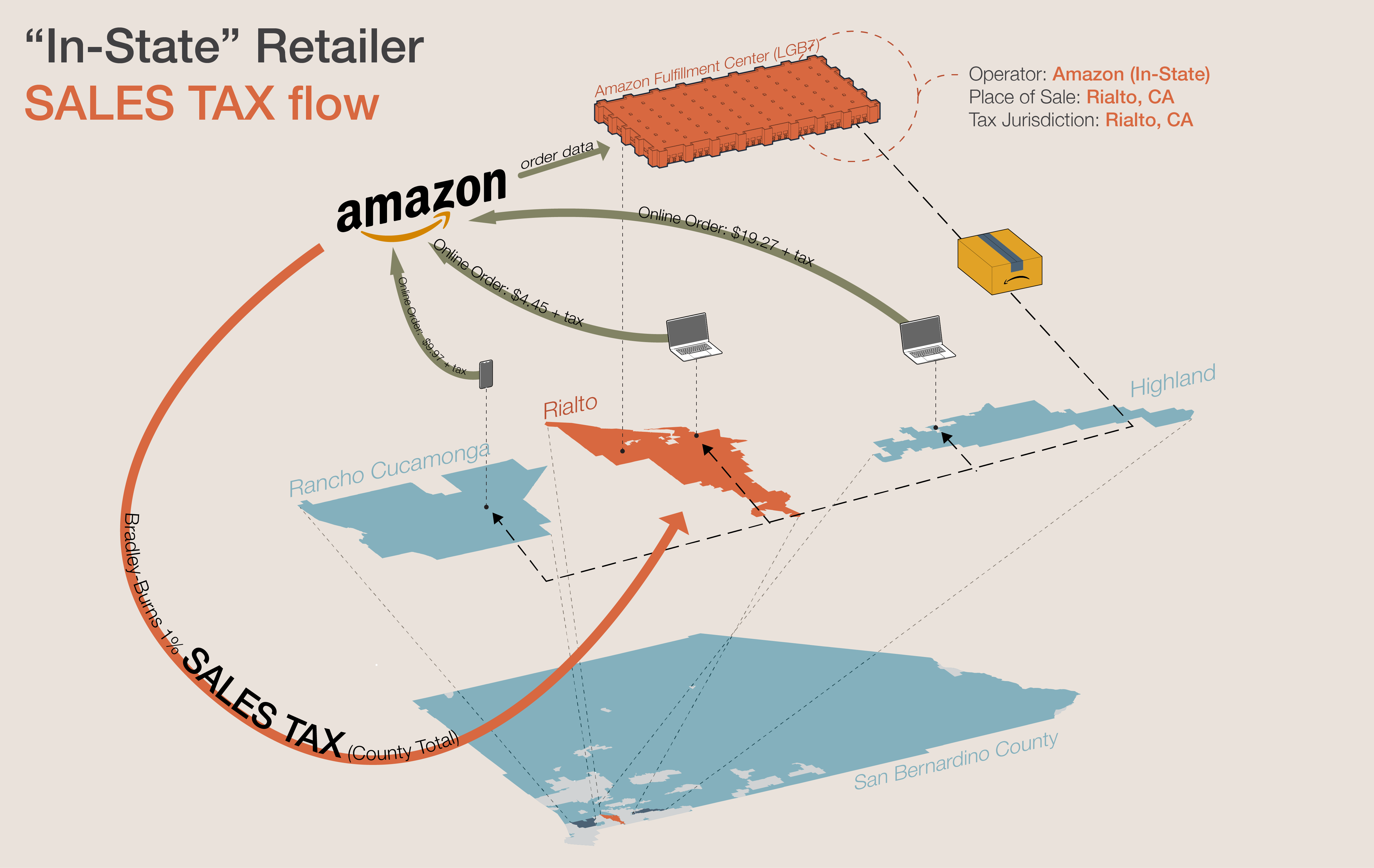

One of the biggest sources of the out-of-state use tax was—to no one’s surprise—Amazon. Prior to 2021, if you made a purchase on Amazon in the city of Rancho Cucamonga, CA, the item that you purchased would come from the fulfillment center in the nearby city, Rialto. Because Amazon was considered out-of-state at the time due to the fulfillment centers being run by an out-of-state third party company, the 1% of the tax you paid at the time of your purchase (alongside that of your neighbors in nearby cities in the county) would be pooled at the county level—San Bernardino—where the “place of sale” belongs, and redistributed back to the cities.

But in 2021, Amazon restructured its ownership, whereby the fulfillment centers, which had been operated by a third-party company, were now run by the company itself. This made Amazon an “in-state” retailer under California law, which meant that the 1% tax collected is now considered a sales tax, which is collected exclusively at the city level—in this case, Rialto. This is because California law considers the point at which deliveries are sent (the fulfillment center) as the “place of sale.”

This did not matter much when Amazon was considered an out-of-state retailer because no matter where in the county the fulfillment centers were located, the jurisdiction over the use tax belonged to the county. However, with Amazon’s switch to an in-state retailer, what was use tax was now considered sales tax, and it belonged to the city—not the county—where the fulfillment centers were located.

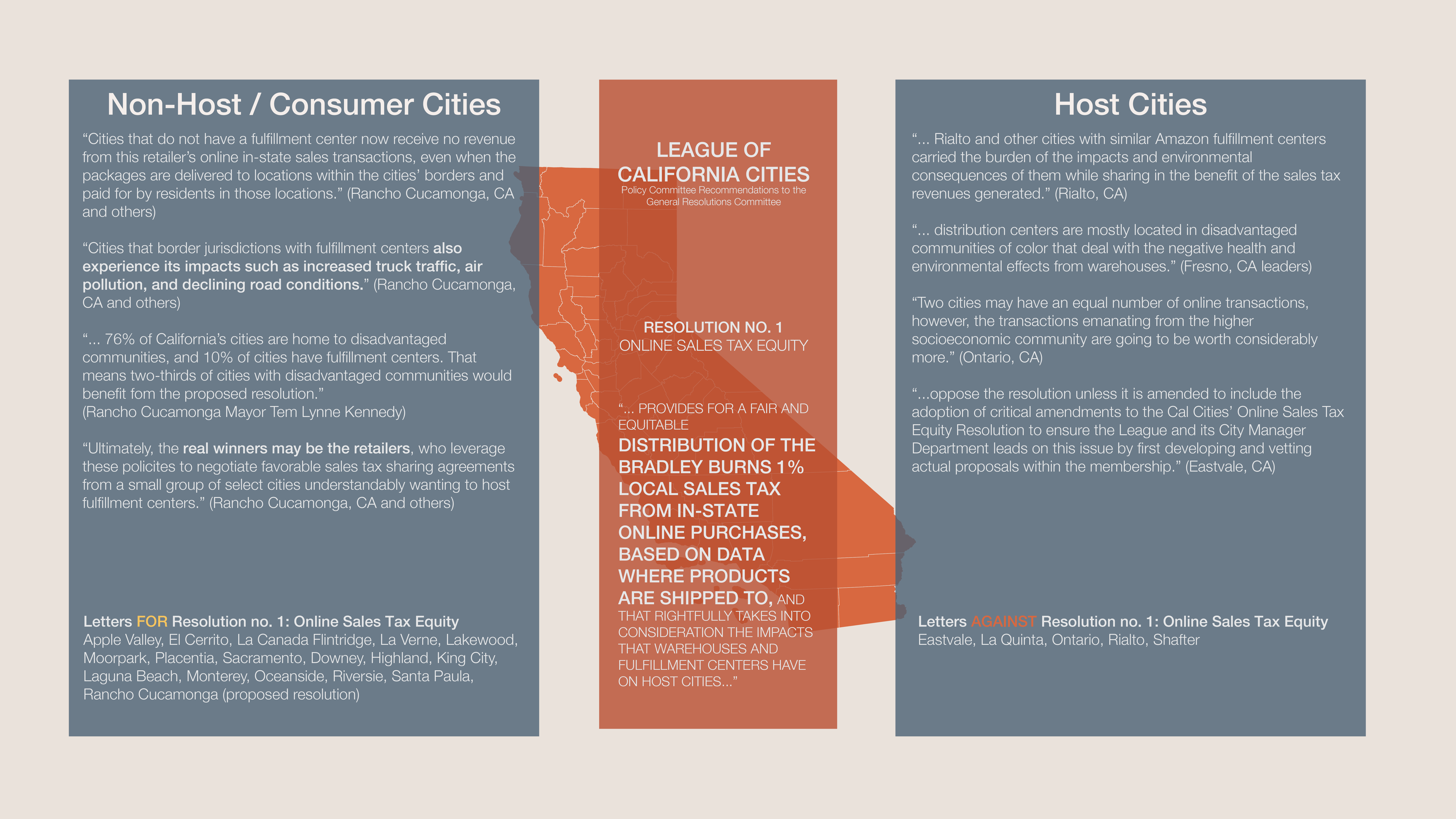

Data source: 2021 League of California Cities Policy Committee Recommendations to the General Resolutions Committee Packet

Data source: 2021 League of California Cities Policy Committee Recommendations to the General Resolutions Committee Packet

Unsurprisingly, this pitted the cities against each other, dividing the cities into two groups: the consumer cities and the host cities. The city of Rancho Cucamonga—a consumer city—proposed a resolution to the League of California Cities (henceforth Cal Cities) that would support a legislation enabling the sales tax proceeds to be distributed to the cities where the goods were delivered to, instead of being distributed to the cities where the goods were delivered from, arguing that the current tax system unfairly favors the host cities. Host cities opposed this proposal, arguing that they were burdened with the bulk of the fulfillment centers’ environmental impact. One Fresno city leader even argued that the proposal is racist because fulfillment centers are largely located in disadvantaged communities of color. Furthermore, host cities argued that the proposal heavily favors cities with wealthier communities who are able to spend more and generate greater sales tax revenues. The main arguments on both sides revolve around the issues of air and noise pollution, traffic increase, and the inequitable impact the fulfillment centers and the sales tax distribution system may have on the cities in each county.

Inter-City Conflicts: County of San Bernardino

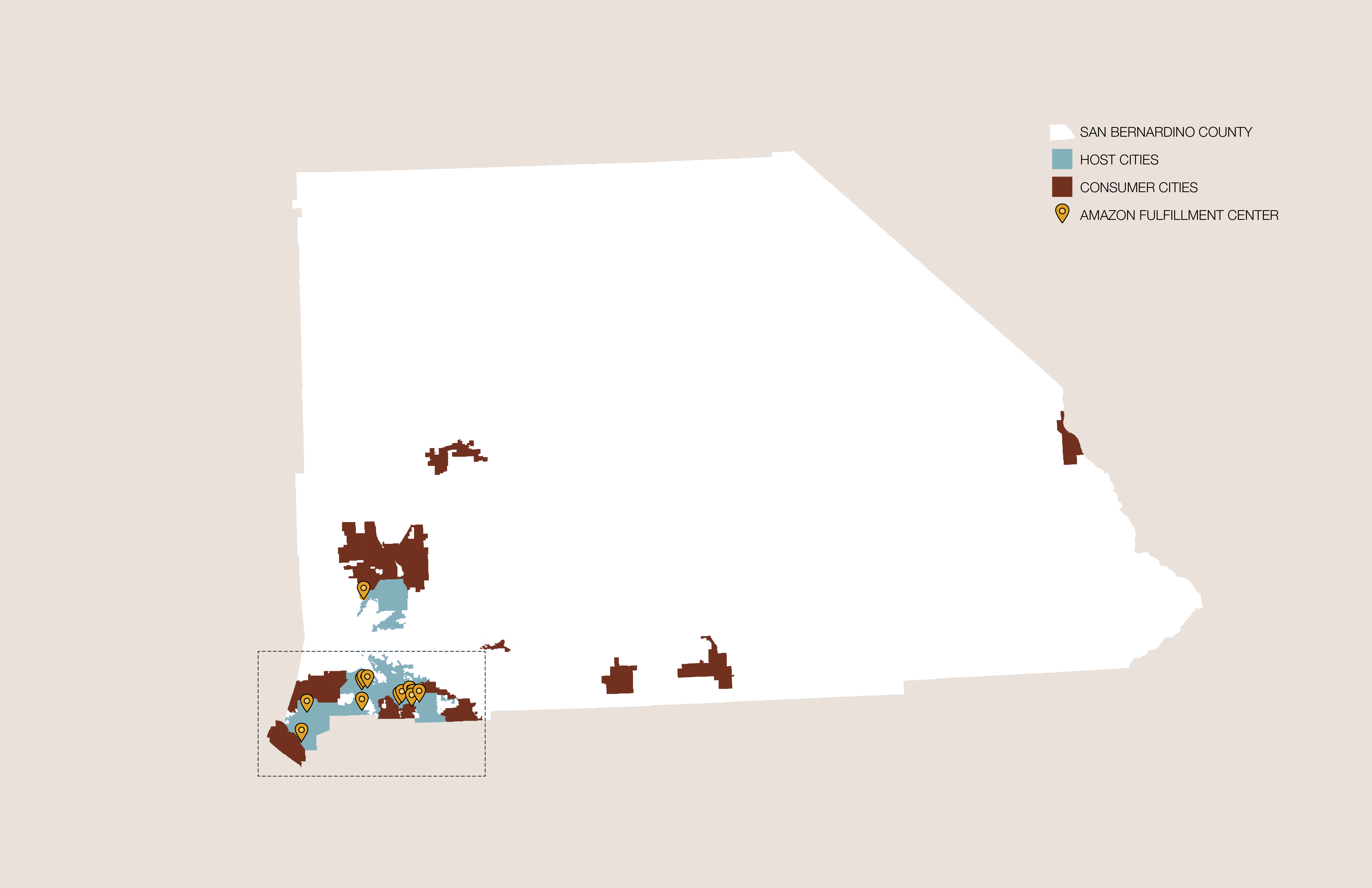

Data source: MWPVL & Good Jobs First

Data source: MWPVL & Good Jobs First

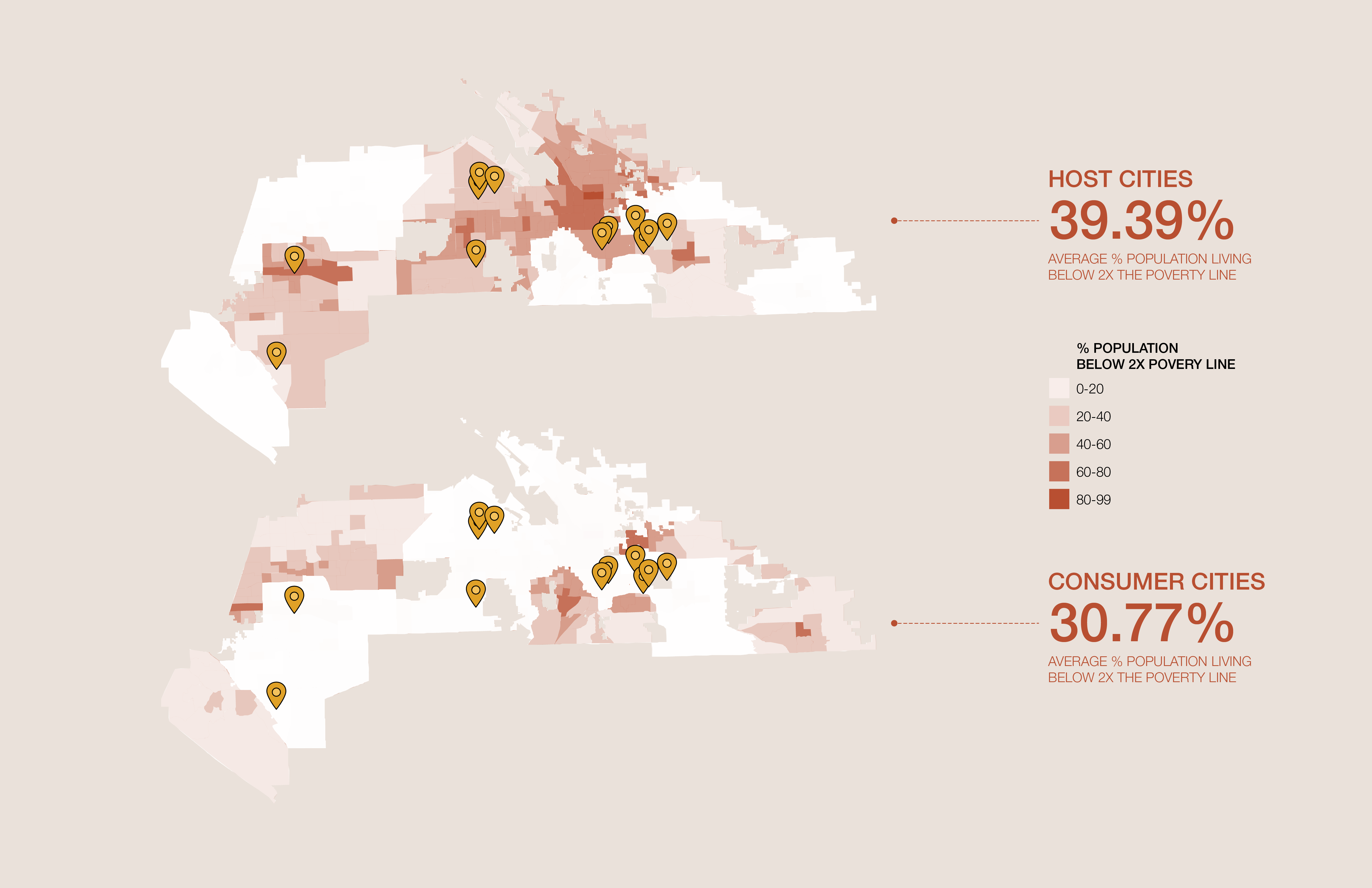

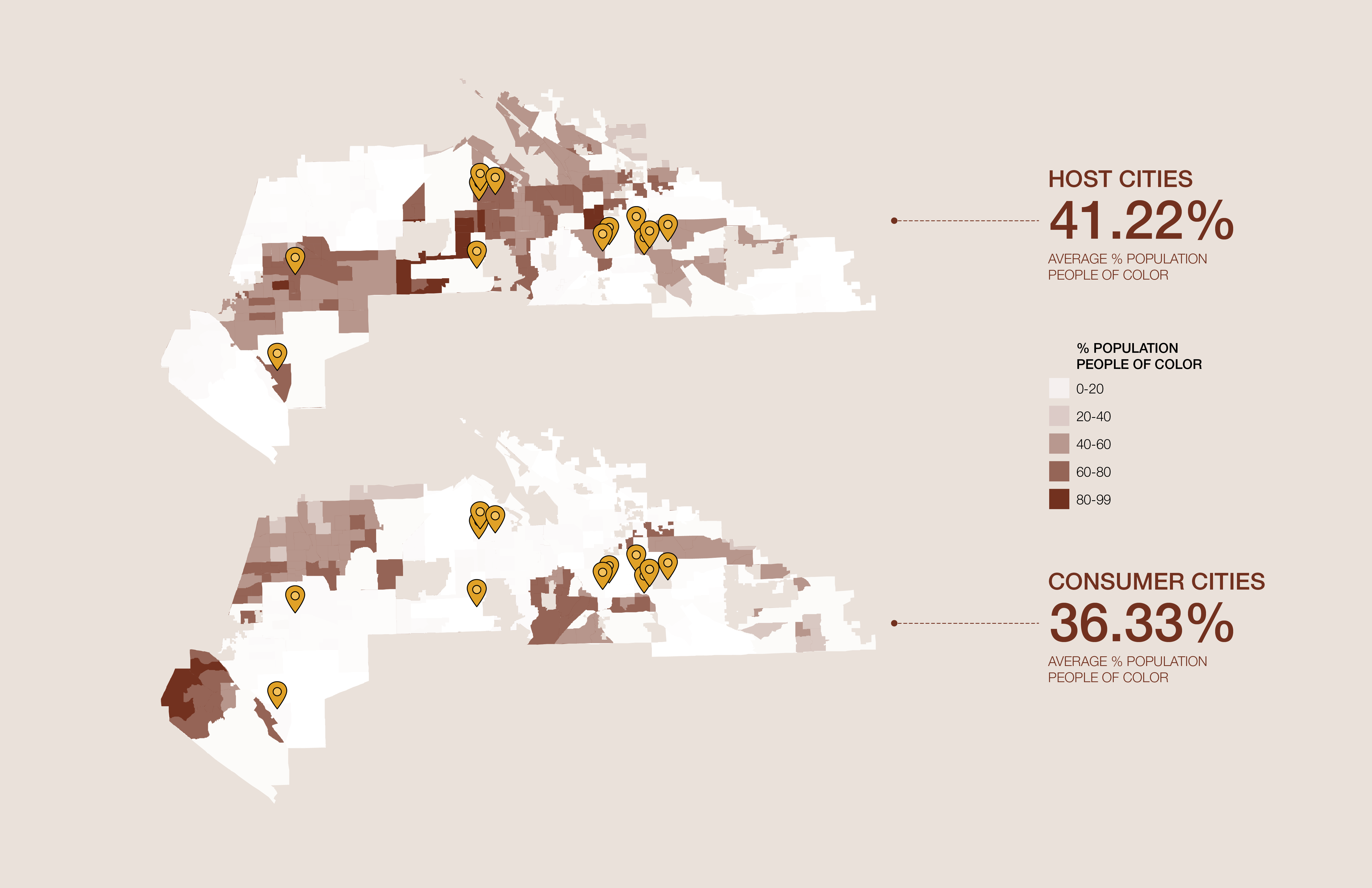

Taking a closer look at San Bernardino County—which has a substantial number of fulfillment centers in close proximity to one another—can help answer some of these questions2. Although the mere presence of a fulfillment center cannot indicate causation, the question that this investigation asks is one about equity: are host cities more disadvantaged than non-host cities in terms of environmental hazard and socioeconomic status – and how are these discrepancies distributed among historically disadvantaged racial groups? More specifically, do host cities, and their residents, experience greater levels of pollution and poverty, and do these cities house a higher percentage of people of color?

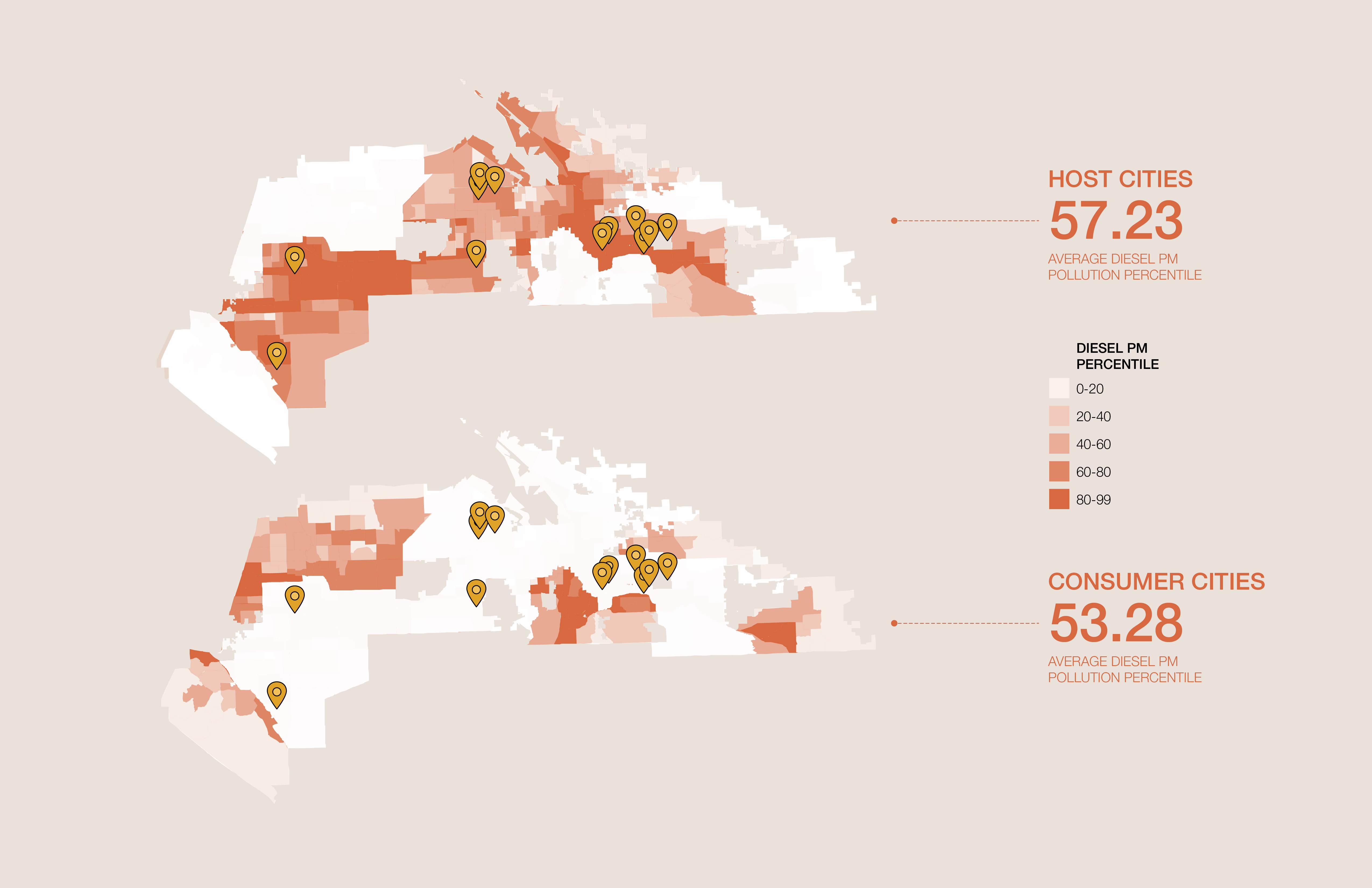

Data Source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Data Source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

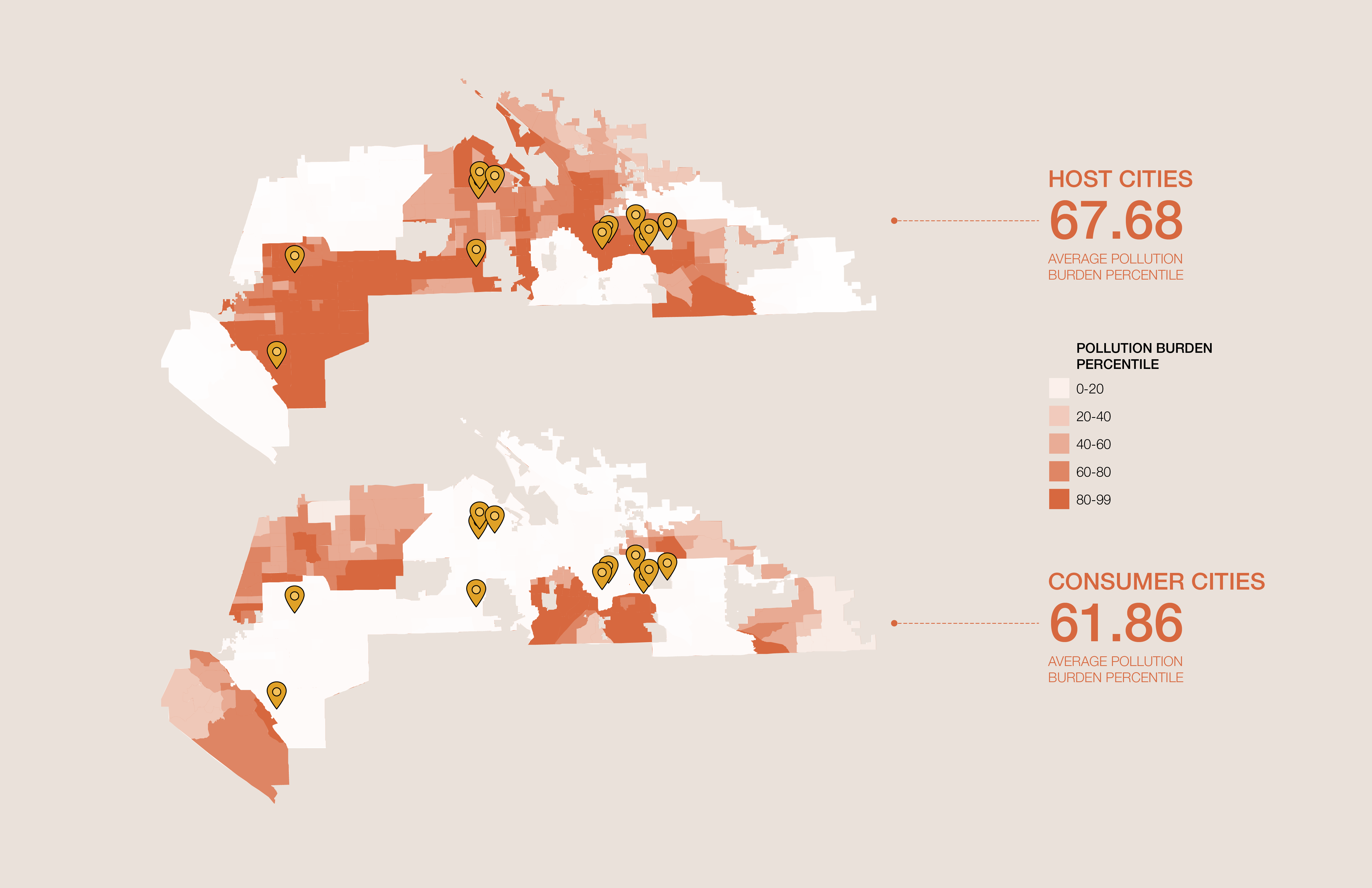

Data Source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Data Source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

When a new Amazon facility is opened, its impact expands beyond the physical structure of the fulfillment center. Not only do nodes along the Amazon delivery network conjure a substantial influx of semi trucks and delivery vans–which spew noxious pollutants into the air– they also prompt an influx of commuter traffic. Increases in traffic results in more treacherous roads for commuters and drivers alike, and nearby residents are left to deal with the consequences of diminished road safety, increased noise pollution and worsened air quality.

Diesel particulate matter (PM) is one hazard expelled from the exhaust of transportation vehicles and industrial equipment with diesel engines. Diesel PM can be incredibly harmful to individuals and is associated with a number of health complications including heart disease, lung disease, and cancer. The map above indicates that on average, host cities in San Bernardino County do experience elevated levels of Diesel PM relative to their adjacent non-host counterparts. It is worth noting that generally, the region as a whole has some of the worst air quality in the country. Looking more broadly across an aggregate of pollution indicators, host cities once again edge out adjacent non-host cities with regards to their average pollution burden percentile.

Data source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Data source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Through looking at the population and demographics data, we can then see whom the environmental pollution is affecting the most. Generally, Amazon tends to locate its fulfillment centers in markedly poor areas, which means that on one hand, residents in these areas are perhaps greatly in need of stable work – but this may come at the expense of the pollution impacts highlighted above. On the other hand, however, poorer communities are often more at-risk for negative health outcomes and they are afforded less social mobility—as individuals at or below the poverty line are greatly restricted in their ability to select an ideal living scenario. Also of note, communities with the most Amazon warehouses nearby have the lowest rates of Amazon sales per household – meaning they face the most direct environmental repercussions of the fulfillment centers with little benefit. In the southwest region of San Bernardino County, the number of people living below two-times the federal poverty level is notably higher in host cities, when compared to non-host cities in the region.

Data source: US Census (2020 ACS 5-Year Estimates)

Data source: US Census (2020 ACS 5-Year Estimates)

This trend also persists along the racial demographics of these cities. Almost 70% of warehouses are located in neighborhoods with a higher-than-typical proportion of people of color. Thus, the environmental damage that Amazon fulfillment centers cause disproportionately affects non-white Californians. Host cities in Southwest San Bernardino County generally have more residents of color than the nonhost cities that surround them. Therefore, it appears that host cities are indeed facing an unequal distribution of negative externalities as a result of the expanding Amazon distribution network. We must note here however, that this does not necessarily mean that the non-host or “consumer” cities are completely unaffected by the negative externalities of the Amazon distribution network due to their relative proximity to the warehouses, as can be seen in the PM data maps.

These kinds of spatial inequities also exist within the city scale. In order to further examine these conflicts, we look at the city of Fresno—a city that is relatively isolated in its bureaucratic geography, with Clovis being the only other city that borders it. Its relative isolation allows us to eliminate many of the variables that affect the metrics we are examining at the intra-city scale. While we acknowledge that there exist inter-city conflicts between Fresno and Clovis, this study will focus mainly on the city of Fresno.

Intra-City Conflicts: City of Fresno, CA

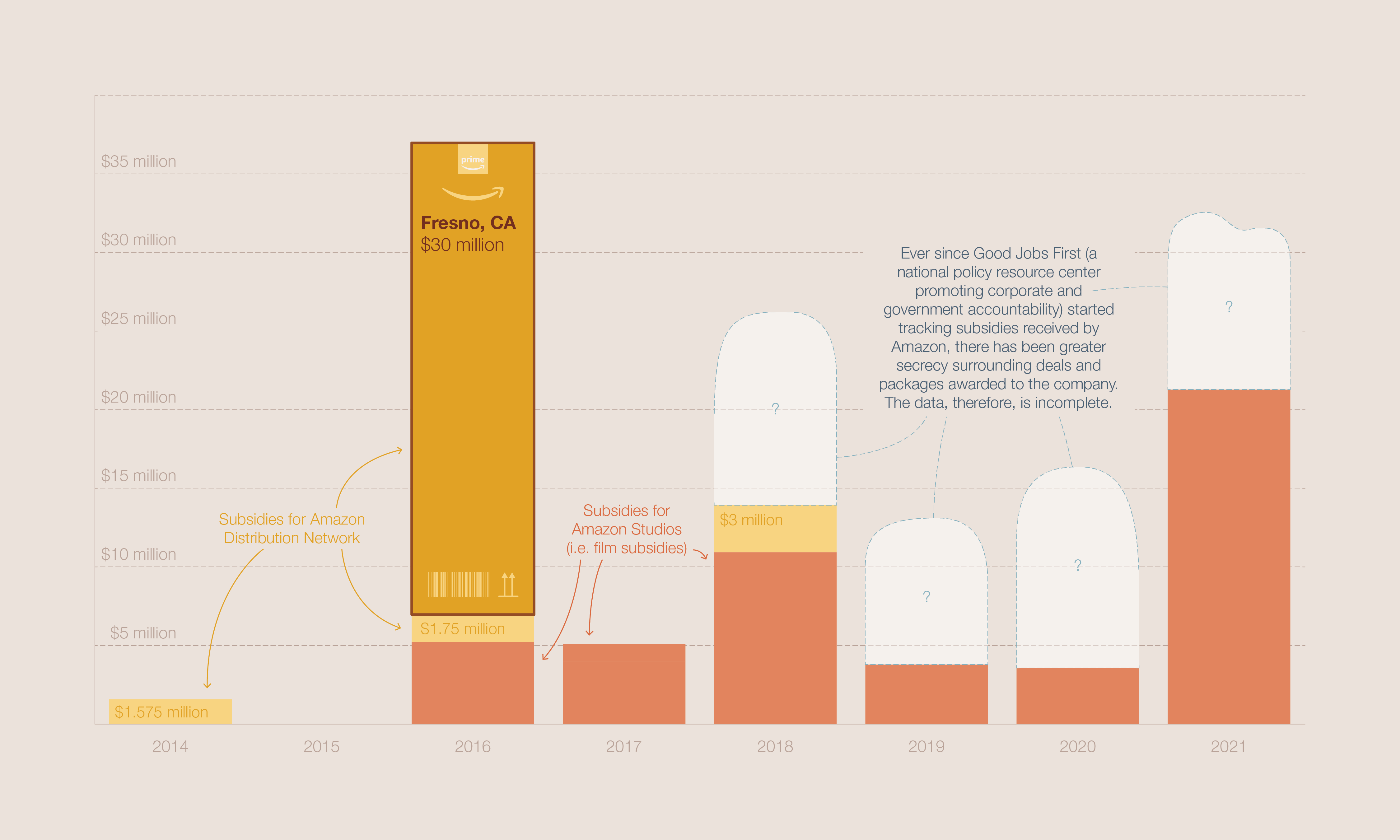

For over a decade, states, counties, and cities have offered subsidies to Amazon in exchange for the opportunity to host a part of the e-commerce giant’s distribution network. With the company’s 2021 restructuring and subsequent changes in sales tax distribution, cities have an even greater stake in hosting fulfillment centers in particular. This also means that—as the company chooses where to locate their facilities—Amazon now has even greater power in shaping the economic well-being of California’s cities.

Date source: Good Jobs First

Date source: Good Jobs First

Although the deals struck between Amazon and city governments have been shrouded in greater amounts of secrecy in the last few years, it is evident that Fresno, CA has given a staggering amount of subsidies to the company. While some counties or groups of cities have given Amazon between one and two million dollars in subsidies, the city of Fresno granted Amazon $30 million worth of subsidies in the form of tax rebates and a 90% property tax discount in exchange for hosting the city’s first Amazon fulfillment center. Now, the city is facing resident pushback for planning to add yet another facility.

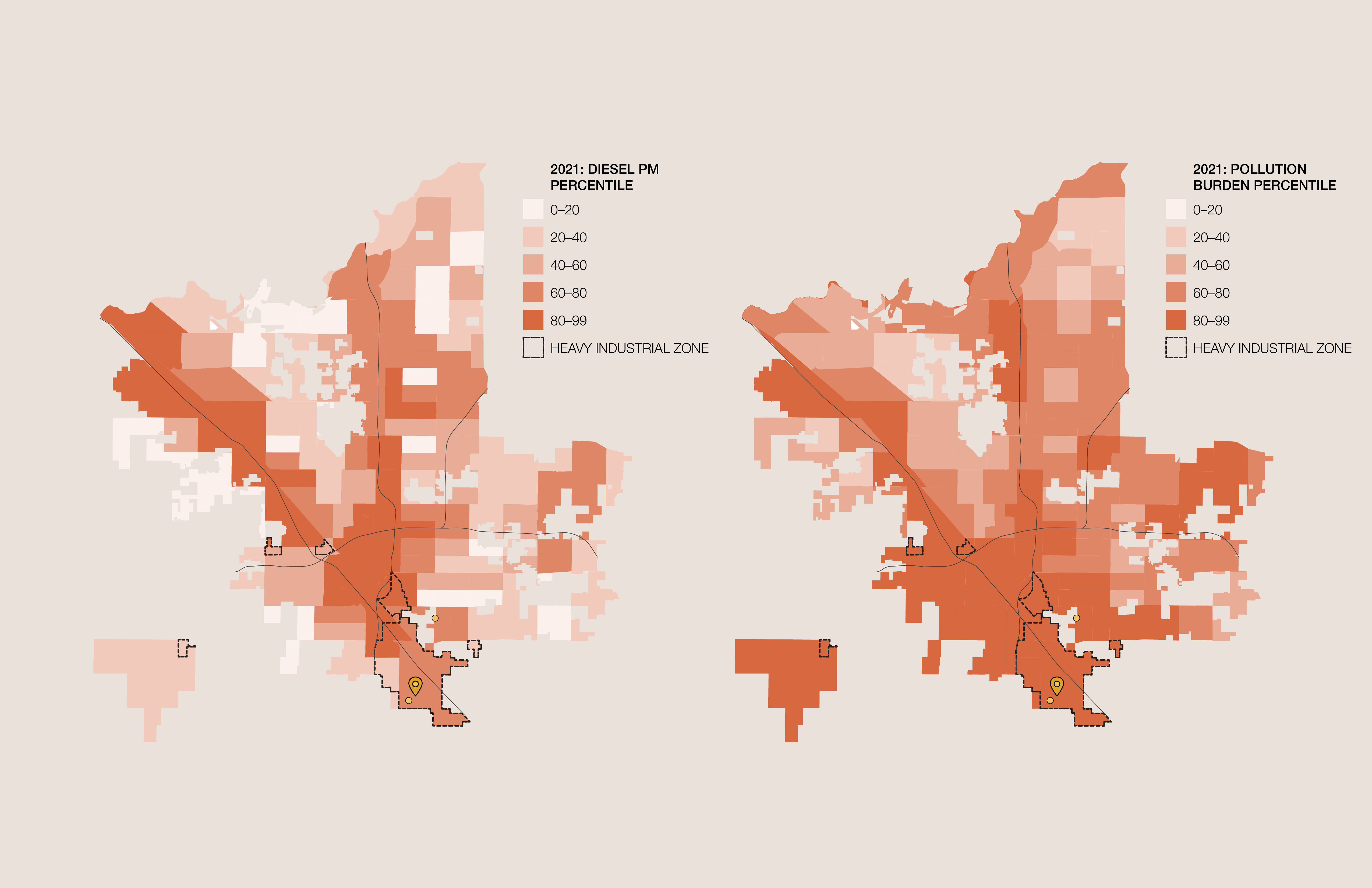

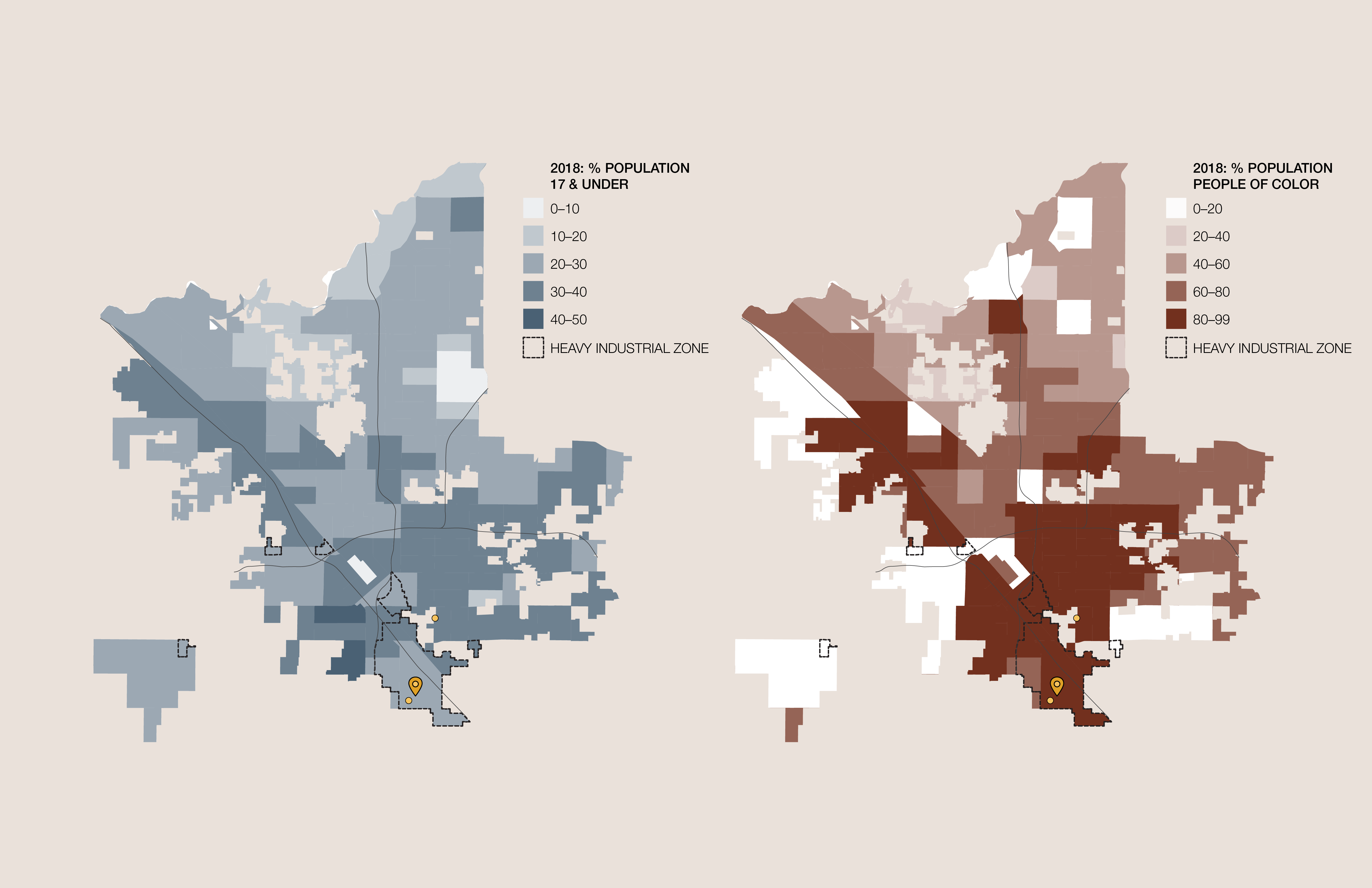

Part of the issue is a zoning problem: the city’s General Plan has designated thousands of acres in South Fresno as an industrial zone, despite a history of residential neighborhoods in the area. The current fulfillment center, as well as the planned facility, fall within this heavy industrial zone, next to houses and schools.

Data source: City of Fresno GIS Data Hub

Data source: City of Fresno GIS Data Hub

Fresno’s industrial plan led residents—namely, the South Fresno Community Alliance—to seek legal action. In 2021, the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability (LCJA) represented the alliance and filed a petition to challenge Fresno’s approval of the Program Environmental Impact Report that allowed for the industrial zone designation. As of early 2022, the city and the LCJA negotiated a settlement agreement: per the agreement, the warehouse developer must contribute $300,000 to a community benefit fund that helps residents make improvements to their homes to offset the environmental impacts of the project.

What, then, are the environmental conditions linked to this heavy industrial zone?

Data source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Data source: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

Here, the residents’ case against Amazon and Fresno’s General Plan appears to have strong validity. South Fresno suffers from a disproportionate amount of diesel particulate matter and pollution overall.

Data source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry & US Census (2020 ACS 5-Year Estimates)

Data source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry & US Census (2020 ACS 5-Year Estimates)

When one considers that these polluted zones overlap with areas that house a higher percentage of children, the effects of such pollution become even more serious. These polluted industrial zones also overlap with communities of color, showing that race and political inequity go hand in hand.

Data source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry & Statista

Data source: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry & Statista

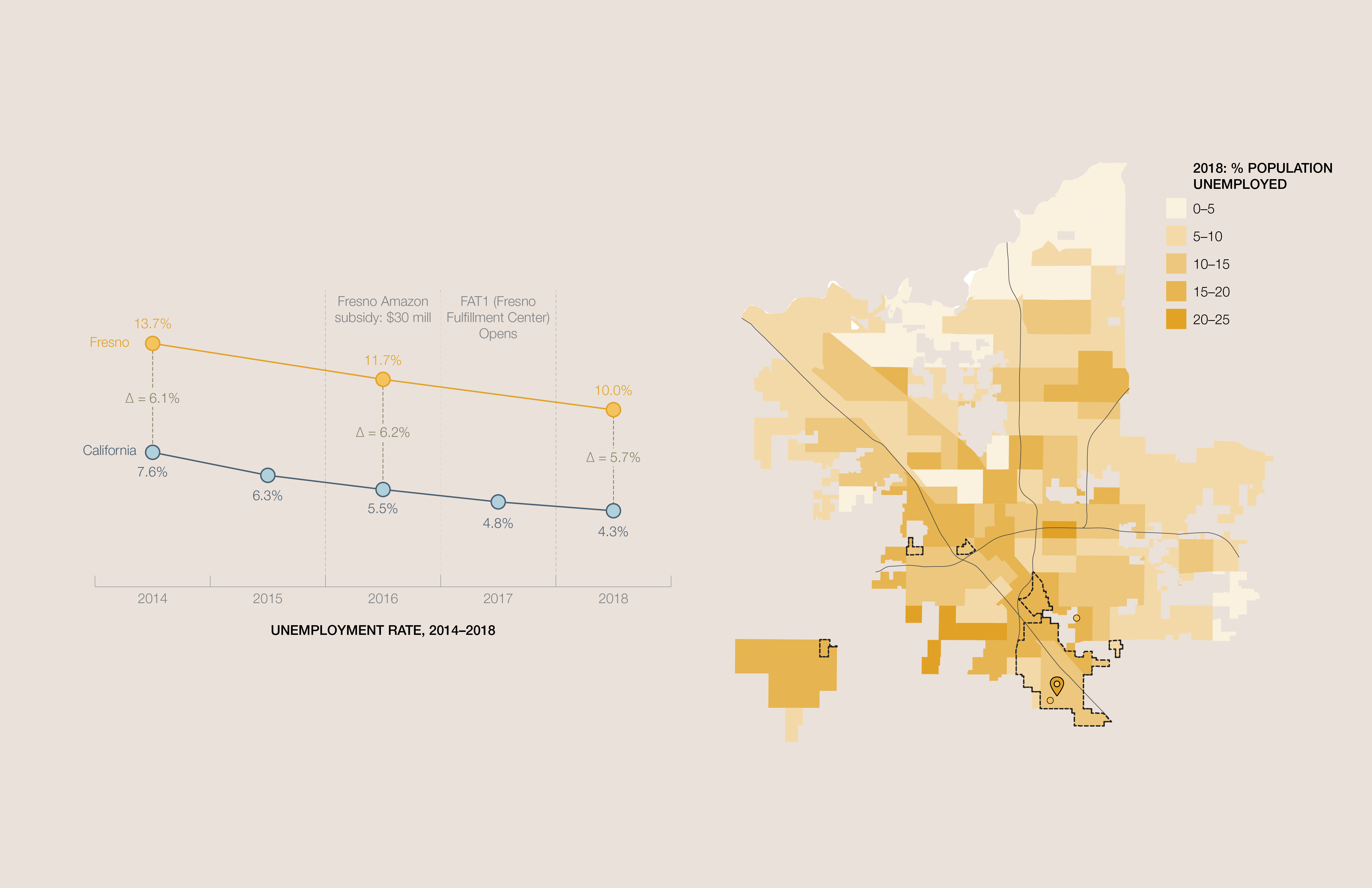

A main argument for cities who are looking to host Amazon facilities is that these warehouses bring a good number of jobs into the area. This begs the question: are the workers employed in these facilities even residents of the host cities? When examining Fresno’s unemployment rate over time, it becomes clear that the city’s unemployment rate remains high above the state average, and has not significantly decreased that gap. Moreover, the communities of South Fresno—the most disenfranchised neighborhoods who bear the brunt of the industrial zone’s effects—continue to have a higher unemployment rate than the whiter, more northern parts of the city. Thus, it is arguable whether Fresno’s $30 million investment was truly worth it.

Conclusion

We must recognize that of course, Amazon fulfillment centers are often situated alongside other warehouses of significant size, and that the aforementioned issues are usually compounded by the effects of those warehouses combined. Therefore, many of the issues discussed here are not simply isolated to the case of Amazon, but rather expanded onto the larger mass-commerce system. That said, the case of Amazon gives us insight into the ways in which counties, cities, communities, and corporations are entangled through the issues of bureaucracy, environment, politics, capital, and equity. The resolution put forth by the city of Rancho Cucamonga and the subcommittee for the Online Sales Tax Equity was reviewed by the General Committee of Cal-Cities and was returned to the subcommittee for further investigation—it is therefore an ongoing issue. Our own investigation reveals that at every scale, Amazon is the entity that comes out on top. Addressing these conflicts—of environmental justice and economic equity—at the intra- and inter-city levels is clearly not enough: instead, what needs to be further addressed is the overlooked conflict between the cities of California and Amazon itself.

Endnotes

-

We acknowledge that the city of Clovis directly borders the city of Fresno, and that in fact, there are most likely numerous conflicts between the two cities over the same issues that are prevalent in San Bernardino. The lack of other cities bordering Fresno, however, does eliminate many of the variables that exist in areas that are densely bordered like those in San Bernardino, Riverside, or Los Angeles counties, which made Fresno an appropriate choice for a closer look within the city.

-

We would like to acknowledge certain limitations to the scope of the study for this section. For one, Riverside county immediately south of San Bernardino County has a similar make up of dense host and consumer cities in its northwest corner of the county boundary, adjacent to the cities in San Bernardino that we are looking at. Secondly, we also acknowledge that the county to the west of San Bernardino, Los Angeles County, has a number of cities bordering the boundary line between both counties, and that these cities host only one fulfillment center, yet dozens of delivery hubs. This is in nearly direct opposition to the Amazon facility makeup of both San Bernardino and Riverside counties, whose make up is overwhelmingly composed of fulfillment centers, with much fewer delivery hubs—as can be inferred in the title diagram.

Works Cited

“Amazon Announces New Fulfillment Center in Fresno.” City of Fresno. Fresno.gov. June 2, 2017. https://www.fresno.gov/news/amazon-announces-new-fulfillment-center-in-fresno/

“Amazon Tracker.” Good Jobs First. Last modified January 2022. https://www.goodjobsfirst.org/amazon-tracker

Bedoian, Vic. “South Fresno Residents Challenge Warehouse Invasion.” Community Alliance. FresnoAlliance.Com. Last modified January 01, 2022. https://fresnoalliance.com/south-fresno-residents-challenge-warehouse-invasion/

Bishop, Todd. “As Amazon booms in California, cities want state to fix ‘tremendous inequity’ in sharing of tax revenue.” GeekWire. September 2, 2021. https://www.geekwire.com/2021/amazon-booms-california-cities-want-state-fix-tremendous-inequity-sharing-tax-revenue/

Brianna Calix. “California cities want a slice of Amazon sales tax. Here’s why Fresno calls one plan ‘racist’.” The Fresno Bee. October 06, 2021. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article254684807.html

“Cal. Code Regs. Tit. 18, § 1802 - Place of Sale and Use for Purposes of Bradley-Burns Uniform Local Sales and Use Taxes.” Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.law.cornell.edu/regulations/california/Cal-Code-Regs-Tit-18-SS-1802

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. “Detailed Description of the Sales & Use Tax Rate.” CA.gov. 2022. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/taxes-and-fees/sut-rates-description.htm

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. “District Sales and Use Tax Rates.” CDTFA 105 Rev. 25 (4-22). CA.gov. 2022. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/formspubs/cdtfa105.pdf

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. “Quarterly Distribution of Bradley Burns 1% Local Sales and Use Tax.” CA.gov. 2022. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/dataportal/dataset.htm?url=LRBQtrAllocBradleyBurns

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. “Uniform Local Sales And Use Tax Law.” CA.gov. 2022. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/lawguides/vol1/ulsutl/7203-1.html

California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. “Uniform Local Sales And Use Tax Regulations.” CA.gov. 2022. Accessed April 16, 2022. https://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/lawguides/vol1/ulsutr/uniform-local-sales-and-use-tax-regulations-art19-all.html

Calix, Brianna. “A second Amazon fulfillment center is coming to Fresno. Neighbors are pushing back.” The Fresno Bee. Last modified March 11, 2021. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article249829748.html

Calix, Brianna. “California cities want a slice of Amazon sales tax. Here’s why Fresno calls one plan ‘racist’.” The Fresno Bee. Last modified October 06, 2021. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article254684807.html

Calix, Brianna. “‘Unprecedented’ agreement paves way forAmazon neighbors, Fresno industry to coexist.” The Fresno Bee. Last modified March 11, 2021. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article249877523.html

Denny, Emily. “Amazon Warehouses Linked to Environmental Injustice in Southern California, Report Finds.” EcoWatch. April 16, 2021. https://www.ecowatch.com/amazon-warehouses-environmental-injustice-pollution-2652607518.html

“Diesel Particulate Matter - OEHHA.” n.d. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen/indicator/diesel-particulate-matter.

Good Jobs First. “Mapping Amazon 2.0.” Good Jobs First. ArcGIS Storymaps. December 23, 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/144d21045a794cf8b7834b0c49fdd0c0

League of California Cities. “Policy Committee Recommendations to General Resolutions Committee.” Presented at 2021 Annual Conference & Expo, Sacramento, September 22-24, 2021. https://www.calcities.org/docs/default-source/advocacy/2021-pc-recommendation-packet.pdf?Status=Master&sfvrsn=cd2ca749_3

MWPVL. “Amazon Global Supply Chain and Fulfillment Center Network.” MWPVL International. Last modified 2022. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://mwpvl.com/html/amazon_com.html

“Riverside County, CA Sales Tax Rate.” Sales-Tax.com. Last Modified April 1, 2021. https://www.sale-tax.com/RiversideCountyCA

Roach, Caillie. 2020. “Air Pollution in the Inland Empire.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. December 6, 2020. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/fe2811197ce1427db17a808593f1526e.

Rodriguez, Robert. “‘Enough is enough.’ Fresno residents sue over new environmental review plan for the city.” The Fresno Bee. Last modified November 03, 2021. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/politics-government/article255487361.html

Torres, Ivette, Anthony Victoria, and Dan Klooster. “WAREHOUSES, POLLUTION, AND SOCIAL DISPARITIES: An Analytical View of the Logistics Industry’s Impacts on Environmental Justice Communities across Southern California.” People’s Collective for Environmental Justice, April 14, 2021. https://earthjustice.org/sites/default/files/files/warehouse_research_report_4.15.2021.pdf

“When Amazon Expands, These Communities Pay the Price - Consumer Reports.” n.d. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.consumerreports.org/corporate-accountability/when-amazon-expands-these-communities-pay-the-price-a2554249208/.