Camp Urbanism

CAMP URBANISM: MATRIX ACROSS GEOGRAPHIES

CAMP URBANISM: MATRIX ACROSS GEOGRAPHIES LABELS

INTRODUCTION + CONTEXT |

Migration at large - whether forced or voluntary - physically manifests in what one might term camp urbanism. Camps are an inherently ephemeral urban typology, where logics of time and space are collapsed. While camps are meant to act as non-permanent spaces of shelter, they have often grown increasingly permanent or regulated. Camp Urbanism is the formal typological manifestation of “temporal” structures onto the landscape to accommodate an influx of people and associated objects for a “limited” duration of time often dependent on external factors including war, climate, and capital. At the core of this investigation is the logic of mobility and capital invested or averted, and ultimately the footprint ingrained onto the soil in fluid contexts of migration. Questions of refuge, mobility and migrancy consequently manifest in the discourse around access, policing, and enclosure of bodies, space, and resources.

Camps often look like cities from the vantage point of a satellite. This specific tool allows for a temporal study of such urban formations, giving the impressions of ephemeral cities which appear, disappear, and/or instead continue - sometimes organically but other times systematically. Because examples of this urbanism are often organized by top-down stakeholders and agencies, they share aspects of an ‘urban’ typology like clear boundaries, grids, and homogeneous urban allotments. While these visual formations are not perfectly similar, and the satellite images do not show how voluntary a set of mobilities may be, they all are manifestations of a flux in capital, resources, people, and time. These moments of flux are conflicts, and their results are start-up urban space.

EPHEMERALITY DAIGRAM: TIME x CONFLICT

METHODOLOGY |

These camps in question, which carry a similar typological representation, are by nature programmatically different and their time spans vary drastically. Some camps are recurrent or in flux such as music festivals, which draw a large number of people every year; other camps are created in the aftermath (or during) a humanitarian crisis, such as UN regulated refugee camps around the world, which usually have an outlasting expiration date. Some camps are put in place after a natural disaster to house climate refugees, a state of emergency shelter. Some camps can no longer be called camps, as they have completely merged into the urban fabric they are in and moved from temporary to permanent.

GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS

Honing into three case studies entangled in differing questions of conflict, this investigation centers three camp formations in their differing context:

- Za’atari Refugee Camp, North Jordan

- FEMA Post-Katrina Camp, New Orleans, LA, USA

- Dheisheh Refugee Camp, West Bank, Palestine

CASE STUDIES: GEOGRAPHIC LOCATIONS

The translation between satellite imagery and aerial perspectives reveals a density, formal spatial organization and geographical context that is rendered visible. Through which, commonalities and differences unfold throughout.

CASE STUDIES: SATELLITE x AERIAL VIEWS

01 |

01.1 MIGRATION MAP

Zaatari refugee camp in Northern Jordan, is the planned urban byproduct of the ongoing civil war in Syria. The camp is an urban condition created and curated by several regional and international humanitarian and governmental organizations that mitigate the flow of refugees seeking ‘temporary’ asylum here. From its conception, a main commercial corridor was planned into the camp grid, termed the “champs-elysees” by Za’atari residents - now host to over 3,000 restaurants and businesses. This questions how global organizations and local actors pre-assume the growth and futurity of refugee camps given this context in specific, where the result is a constrained spatial formation with a highly regulated and orchestrated urban footprint and network of resource flows.

01.2 TIME X GROWTH

Zaatari camp was first opened in July 2012 as part of the UN-sponsored relief effort to house refugees forced to leave Syria due to war. The camp was meticulously set-up on desert land 10km East of the city of Mafraq, with roads, fences, shelter and extended electricity grid to become home to roughly 80,000 people within the year.

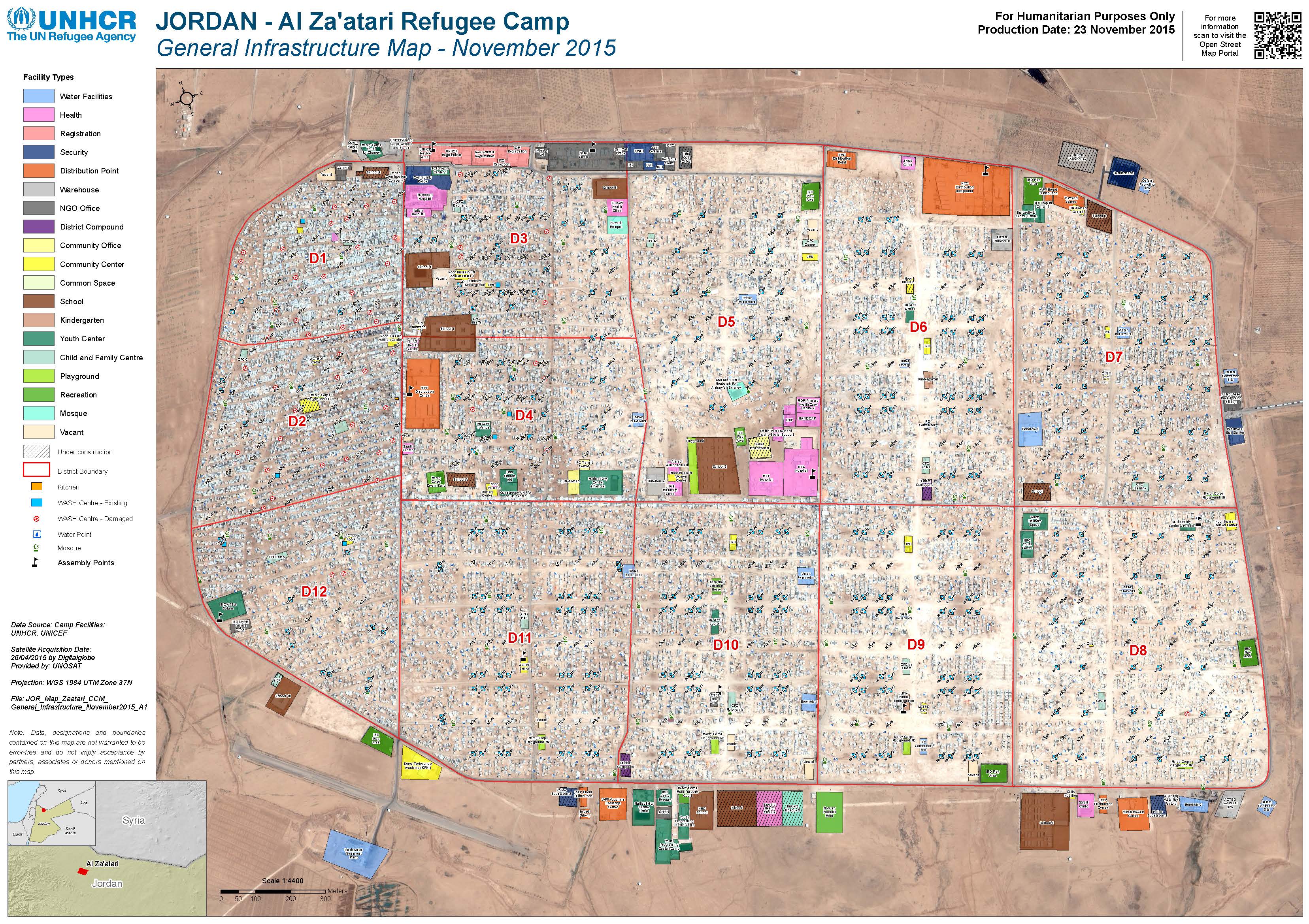

01.3 ZA’ATARI PLANNING AND REGULATION, UNHCR, Nov 2015

Documentation and regulatory practices by governing agencies and bodies feed into a network of resoruces, planning procedures and urban alterations that become available in the case of Za’atari. This specific document by the UNHCR (2015) alludes to the meticulous organizational detail and data at play within this specific context.

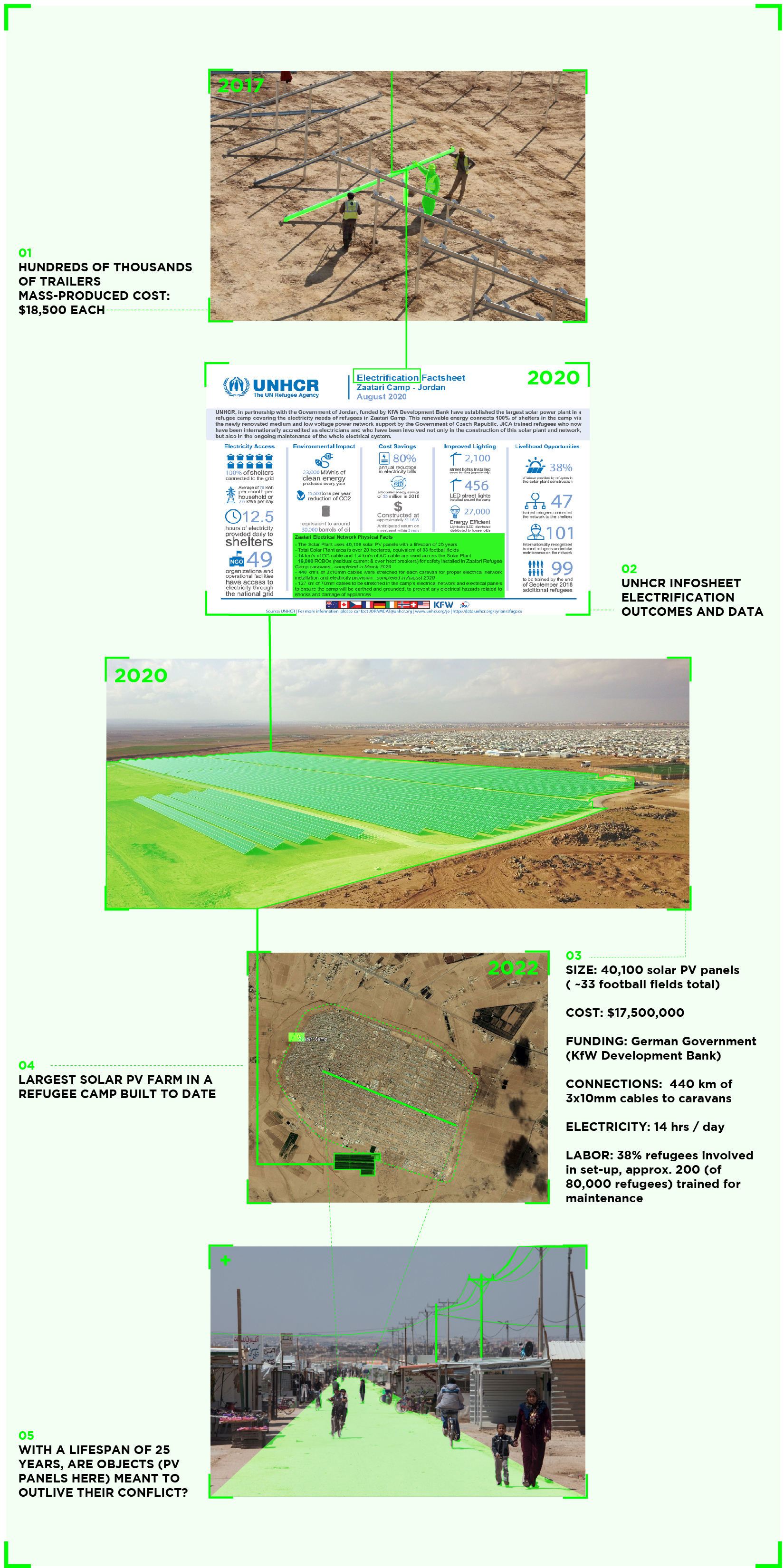

01.4 OBJECT STORY: SOLAR PANELS

In the case of Zaatari, tracing the solar panel grid which powers the camp since 2018 as an object of conflict, forefronts the contested reality of camp, capital and access here. This solar panel farm is the largest in the region and is funded by the German government. Through this influx of resources, an external entity has some sort of power over the camp, a conflict may arise that is not necessarily violent but touches upon other forms of power and control such as foreign reliance.

02 |

02.1 MIGRATION MAP

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2007, FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) established an alternative housing program to house displaced persons in the Gulf region. A complex organization of trailer park-like sites, defined by thousands of temporary housing trailers, was a primary tool for this effort. This site, established in the Lakeview neighborhood of New Orleans, was just blocks from the inundated zone. It resembled a typical American suburban neighborhood, with gridded streets, driveways, and identical homes; a transplant of an idyllic American spatial formation.

FEMA, a powerful and relatively well-funded entity, had a clear influence on how long it lasted as an urban formation. The amount of capital and human resources that the agency was able to move in the few years following Katrina reflected a goal of how camps should operate - that is, temporarily. After an initial cumbersome and error-prone recovery effort in the storm’s wake, in which residents were left without potable water and adequate shelter, the trailer camps eventually housed and moved massive amounts of people. From 2005 until 2012, FEMA housed up to 92,000 displaced residents of southern Louisiana. Now, they have disappeared from the map.

02.2 TIME X GROWTH

This FEMA camp was assembled just blocks away from flood inundated zones in New Orleans. The immediacy of this position indicates both a desire and ability for FEMA to respond to disasters in their relative area, rather than relocate people entirely. This FEMA camp was assembled and disassembled within two years after the initial disaster, according to this series of satellite photos; the site now contains student housing for the University of New Orleans.

02.3 OBJECT STORY: TRAILERS

The story of the trailers involved in this camp effort is evidence of how the availability of capital and human resources can drastically affect the spatial formation and longevity of a city-like camp. The trailers were built quickly and with cheap, toxic materials like formaldehyde. They were quickly set into formation, stayed in the suburban-looking camps for several years, then stored in large fields and eventually sold off at auction at a loss. Much of the discussion and documentation about these trailers is concerned with the specific amounts of the trailers as assets, and the cost to taxpayers for storage after their use. This camp is therefore a vivid example of the capitalization of space and the inherent temporality of cities amidst disasters. In other words, these camps can be seen as the manifestation of capital and effort that is constantly shifting through space.

Alongside this transformation of space through the movement of capital and materials through these trailers, there is an underlying issue of access and equity within this FEMA camp. There is some evidence that there was a racial disparity between people unhoused by the disaster and those that ended up housed in the trailers; researchers observed a disproportionate amount of white residents compared to previous demographics of the area. It is reasonable to assume that although FEMA’s organizational structure was able to create and destroy these camps faster than other similar camps, they were not unaffected by systematic racial biases and disparities.

03 |

03.1 MIGRATION MAP

Established in 1949 to temporarily house more than 3,000 Palestinians expelled from 44 villages of origin, and internally displaced due to the Arab-Israeli war, Dheisheh has since densely grown to accommodate over 15,000 people. The question of refugeeness here is particularly interesting where Palestinians are the only population under the mandate of UN Relief and Works Agency as opposed to UNHCR.

03.2 TIME X GROWTH

Dheisheh began as a tent encampment along the main road leading to Bethlehem, laid out in a military grid-like formation on land leased to UNRWA. It has since transformed into a seemingly permanent city where generation after generation continue to live in this “temporary state”.

03.3 OBJECT STORY: BUILDING MATERIALS

From tensile tents to concrete infrastructures and steel rebar reinforced roofs - a sense of generational growth in seemingly permanent material object transformations are witnessed here. While property cannot be “owned” in camps according to international law, notions of ownership and commodification become visible in Dheisheh.

CONCLUSION |

There is conflict embedded in the creation of camps; curating a series of these urban spaces by their similarity in a top-down aesthetic enables an analysis of disparate formations along a similar lineage of questions and critiques. Satellite images however, the key tool used in this analysis, are inherently misleading. It gives the impression that everything depicted is permanent, planned by some entity in a binding formation, and as sure as the landscape that surrounds every city, town, building, and camp. Traditional urban spaces are not intended to disappear as these images depict to viewers. Their marks in the land seem to be inevitable in the successive top-down images of satellites.

Camps complicate such a feeling; they are created out of desperation and need, rather than opportunity and promise. When a camp is created, it is not intended to stay there or make a mark on the land. Tracking a camp over time must remind us that the permanence of a city is uncertain. Thus, a satellite image is less potent in this tracking than the forces, resources, organizations, and effort that morph a camp’s spatial formation and move the people inside of it. What is the intent of the creator and destructor of camps? Camps need to be viewed not as the result of only conflict, but power where further discourse is interjected into the urban fabric, accumilating streams of ideas, efforts and resources that conglomerate to create a new urban reality.

CITATIONS |

- CDC tests confirm FEMA trailers are toxic. (n.d.). NBC News. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna23168160

- Dheisheh Camp. (n.d.). UNRWA. Retrieved May 4, 2022, from https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/west-bank/dheisheh-camp

- Dheisheh_refugee_camp.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved May 4, 2022, from https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/dheisheh_refugee_camp.pdf

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas. (n.d.). Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/fema-trailers-11265/

- From Camp to City. (2016). https://www.lars-mueller-publishers.com/camp-city

- Gemenne, F. (2015). The Anthropocene and Its Victims. In The Anthropocene and the Global Environmental Crisis. Routledge.

- Google earth Pro 7.3.4.8573 (64-bit) (March 24, 2022). Zaatari Camp, Jordan. 32° 17’ 39.31”N, 36° 19’ 37.44”W, Eye alt 18329 feet.NVIDIA Corporation. http://www.earth.google.com (April 2, 2022).

- Google earth Pro 7.3.4.8573 (64-bit) (March 24, 2022). New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. 30° 02’ 03.73”N, 90° 02’ 34.74”W, Eye alt 10095 feet. NVIDIA Corporation. http://www.earth.google.com (April 2, 2022).

- Google earth Pro 7.3.4.8573 (64-bit) (March 24, 2022). Dheisha, West Bank, Palestine. 31° 41’ 37.10”N, 35° 11’ 04.29”E, Eye alt 12402 feet. NVIDIA Corporation. http://www.earth.google.com [April 2, 2022].

- Home, Za’atari Film. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.zaatari-film.com/

- Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, LA, 1-22-06—A specially designed lifting bar is positioned to lift a FEMA Travel Trailer off the train car. FEMA is delivering about 500 Travel Trailers per day to help house Hurricane Katrina disaster victims. MARVIN NAUMAN/FEMA photo. (2006, January 22). [Image]. The U.S. National Archives. https://nara.getarchive.net/media/hurricane-katrina-new-orleans-la-1-22-06-a-specially-designed-lifting-bar-is-5334d1

- Jordan’s refugee camp that houses 80,000 Syrians. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2018/4/1/syrias-war-inside-jordans-zaatari-refugee-camp

- REACH Zaatari camp General Infrastructure Map—November 2015. (n.d.). UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/44561

- Refugee Camps. (n.d.). UNHCR Jordan. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.unhcr.org/jo/refugee-camps

- Temporary Homes in Permanent Crisis. (n.d.). Power: Infrastructure in America. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://power.buellcenter.columbia.edu/essays/temporary-homes-permanent-crisis

- The Secret History of FEMA, WIRED. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://www.wired.com/story/the-secret-history-of-fema/

- The stories Behind a Line. (n.d.). The Stories Behind a Line. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from http://www.storiesbehindaline.com

- The Unbuilt. (2015, November 16). DAAR. http://www.decolonizing.ps/site/unbuilt/

- UNHCR Zaatari Refugee Camp Fact Sheet—July 2020.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/UNHCR%20Zaatari%20Refugee%20Camp%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20July%202020.pdf

- UNOSAT_A3_Update_AlZaatariCamp_Landscape_20160630.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://unosat-maps.web.cern.ch/SY/CE20130604SYR/UNOSAT_A3_Update_AlZaatariCamp_Landscape_20160630.pdf

- Zaatari Base Map. (n.d.). UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/38315