Toward an Infrapolitics of Borders and People: Deterritorializing and Reterritorializing in Haifa, Palestine and Mahikeng, South Africa

Introduction

This project examines different claims to space and how they are made. We focus on specific cities in Palestine and South Africa to highlight processes of territorial formation in contested milieux and these processes’ lingering afterlives. On the one hand, we advance that claims over space are made through presence, occupancy, and insurgence. On the other hand, claims are made through state-based and technical tools. Mapping defines boundaries of space and representation and tools of zoning, land-use, and law. Mapping structures the rules of spatial and economic development. Resident strategies constitute techniques of infrapolitics; tactics of nation-states and border-making constitute contested re-presentation, or legitimizing space as ‘public’ (see Scott 2012; Latour 2005).

In our case-study contexts, we argue that strategies of ‘deterritorialization’ and ‘reterritorialization’ have aimed to serve larger national-level political ends for projects of racial and ethnic exclusion. Yet on the ground, they also give rise to complex hybridized spaces of dwelling and everyday life.

We focus on Haifa, Palestine, and Mmabatho, Bophuthatswana (now Mahikeng, North-West), looking at changing borders and spatial re-appropriation of buildings and spaces from 1913 to the present. The project considers how both states and residents alternatively appropriate and re-appropriate spaces over time, in hegemonic and defiant exercises shaping what Lefebvre (1974) calls the production of space. Drawing on our local case studies, we explore how States use technologies and logics of urban planning in processes of strategic deterritorialization and reterritorialization of formal borders, property demarcations, and land-use controls. In both Palestine and South Africa, such urban-planning logics cultimate in spaces that sequester, control, and exclude populations by way of race and ethnicity (Clarno 2017). With a focus on 1913-present, we explore these efforts of deterritorializing and reterritorializing, but also explore underlives: infrapolitics of borders and people (Scott 2012; Simone 2004).

Our project proceeds in a multi-scalar form. When examining birds-eye national-scale maps, official technologies of representation and the social construction of borders loom large. However, when zooming down to the scale of cities and neighborhoods, we can glimpse complex hybridization within territorialization.

National Scale

Legal regimes and borders aim to produce space in a way that establishes specific types and categories of citizens and subjects, seeking to clearly assert sovereignty and unique authority over people and land (Mamdani 1996, 183).

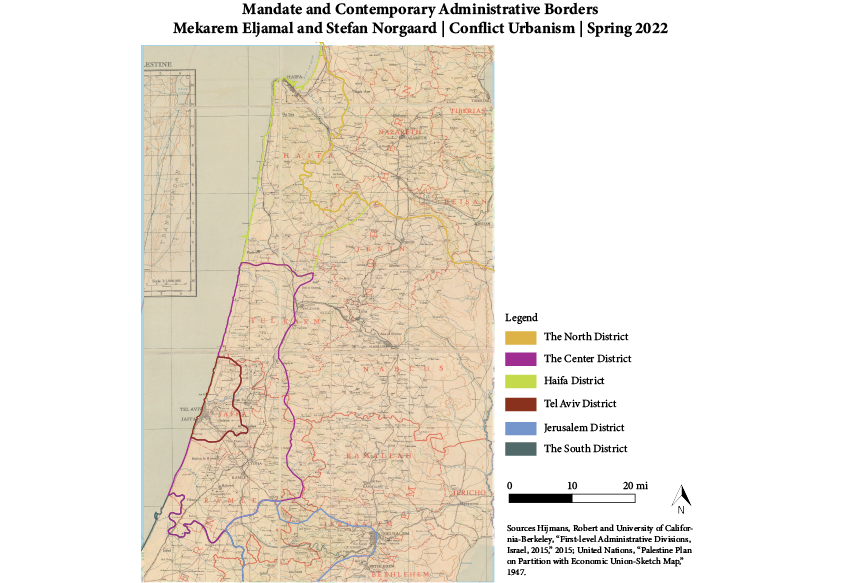

Subject and citizenship is formed through two sets of borders on this Mandate era map. First, through the national boundaries of the Palestine Mandate, depicting the authority of the British colonial government on subjects residing within the boundaries stretching from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River. Then the administrative borders in red represent a second layer of authority, still British authority, but one more proximal to residents.

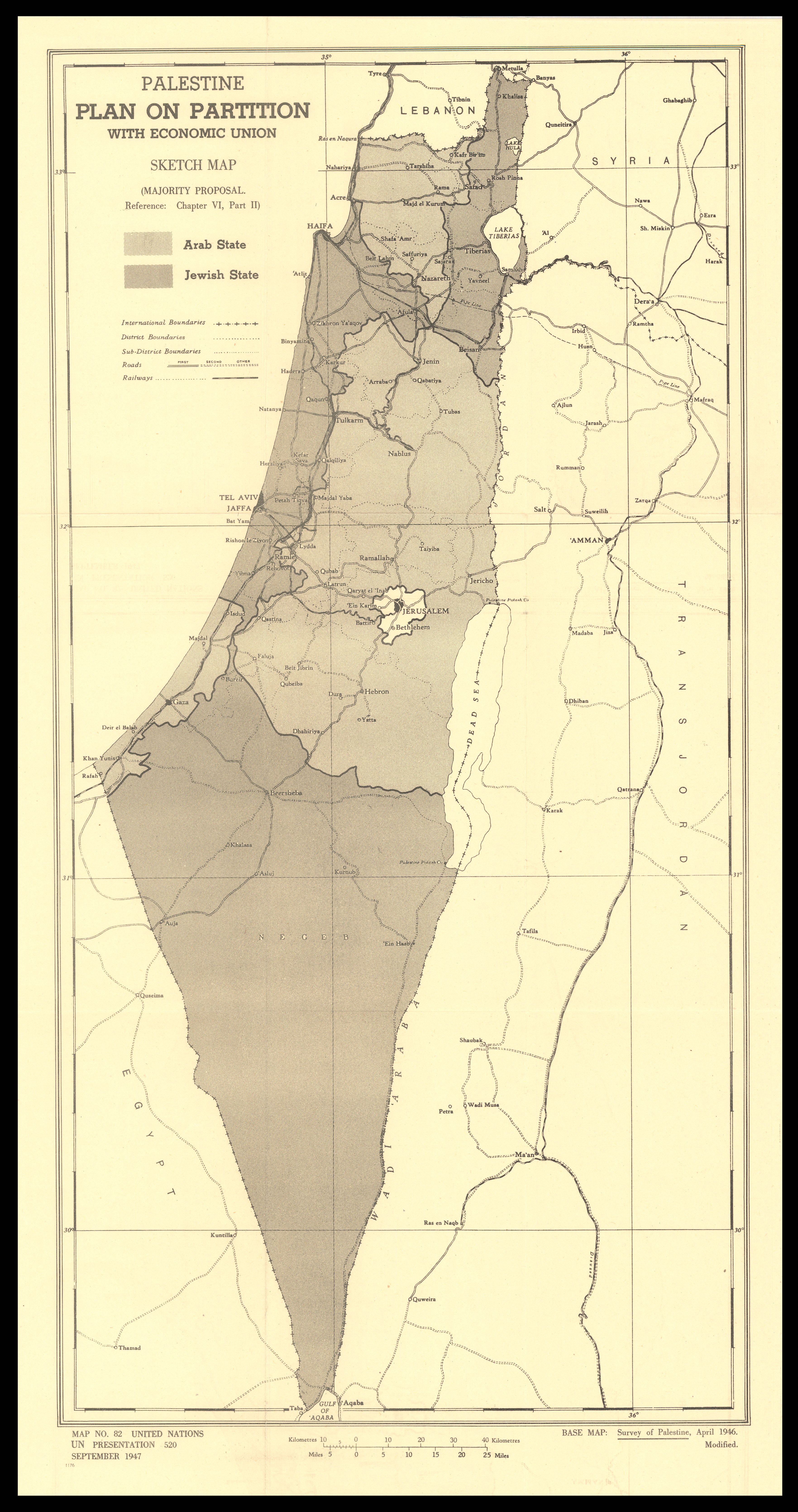

The envisioned division of Palestine into two separate states, a Jewish state and a Palestinian one, hinged around constructing two countries wherein the citizens within the borders aligned with the new governing authority, regardless of the feasibility of such national division. This partition map, and the fact that it was not implemented as depicted, forces a questioning of maps, whether they truly provide clarity and what reality they represent.

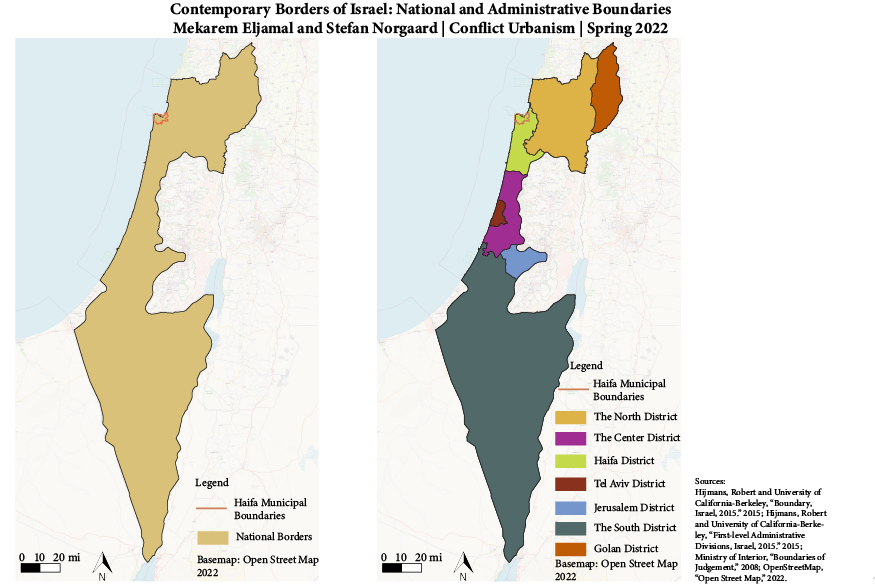

The new Israeli borders continue to redefine the subjects and territories under its authority, stretching its reach further into the territories that the earlier UN partition plan had labeled as Palestinian territories. Important to note, these boundary lines, though, do not account for military and civilian (i.e. settlements) incursions as national-scale territorialization that forcibly and violently expand the scope of Israel’s claimed authority and sovereignty.

What we see with these national-scale maps are territorialization at a distance, disconnected from whether such borders have been realized, whether they are viewed as legitimate on the ground, and whether they are respected both by those constructing the boundary lines and those ostensibly seen as subjects.

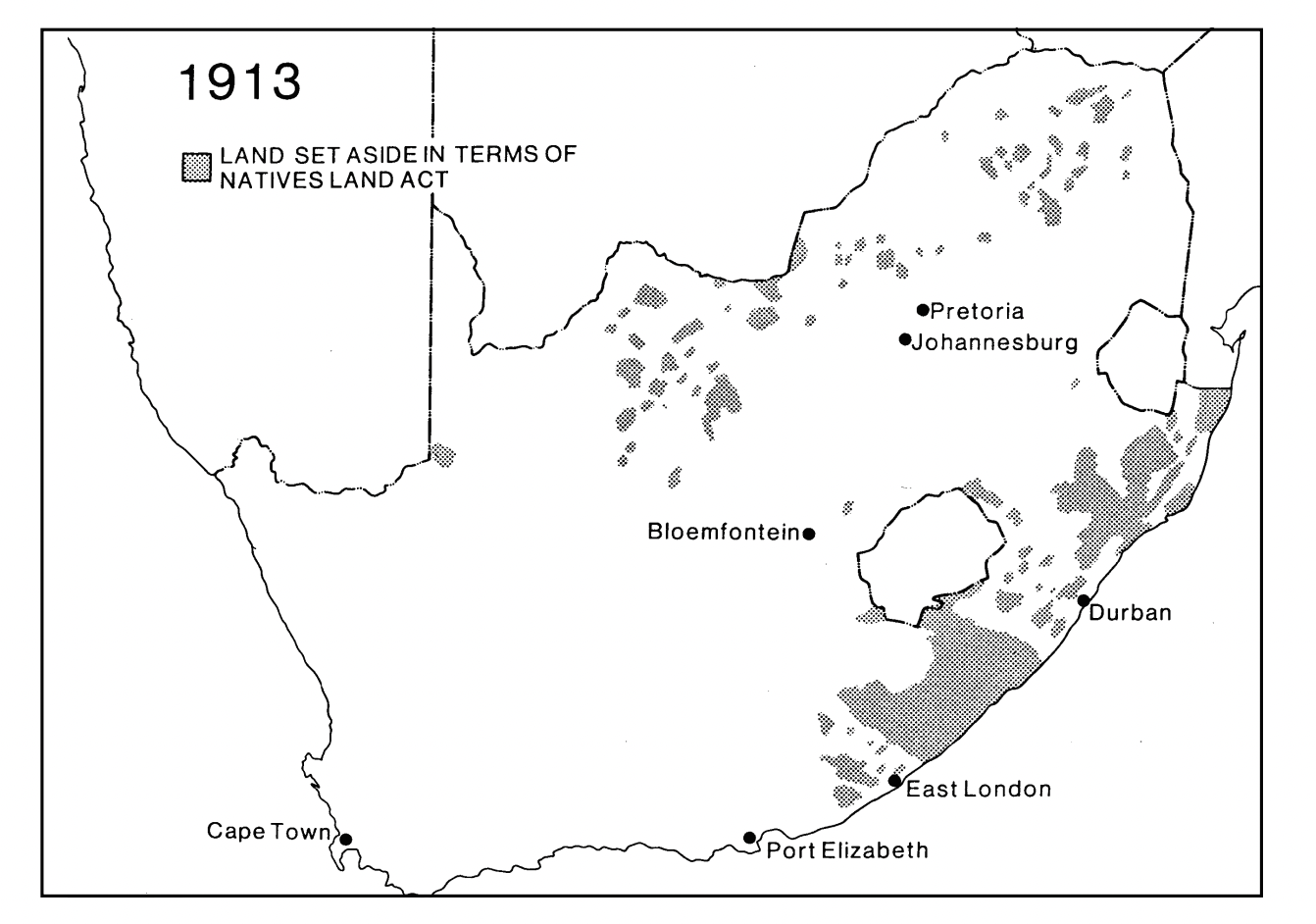

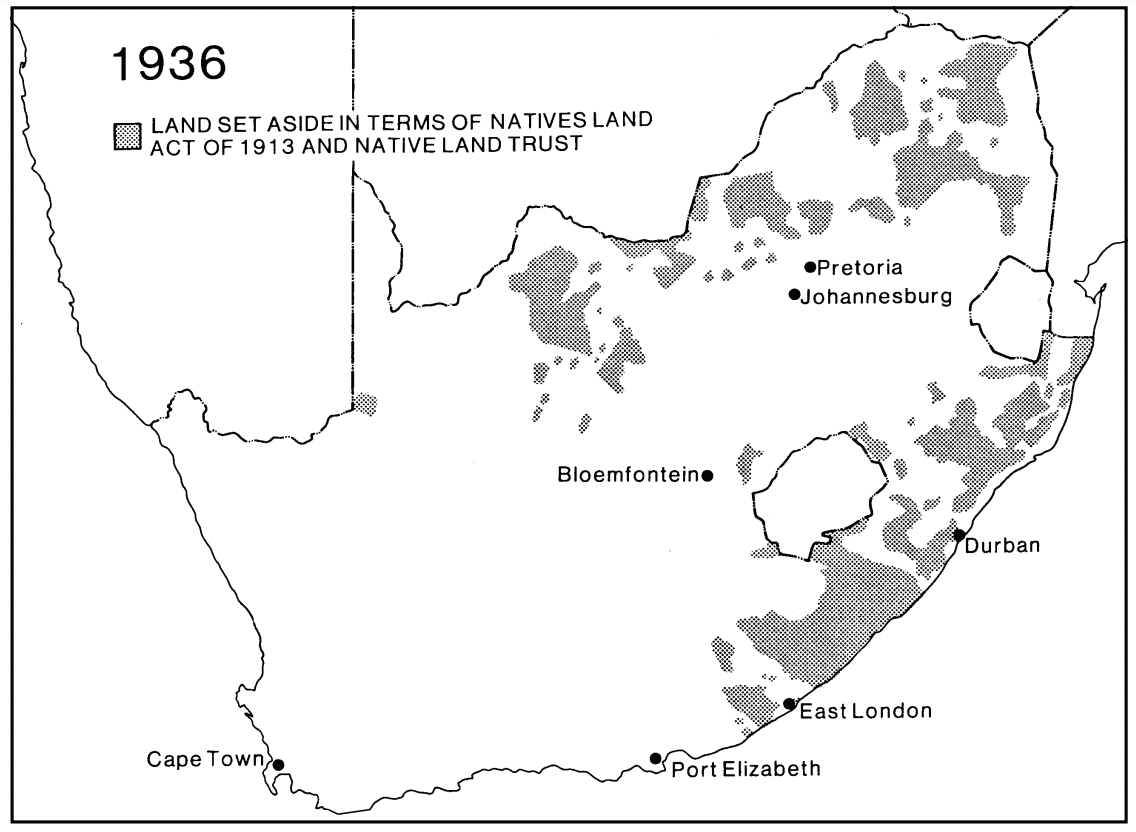

Historical Map of the 1913 and 1936 Natives’ Land Acts (Image from AFRA 1989. Reproduced with permission).

Apartheid was an overarching regimes of differenitated citizenship achieved centrally through spatial logics (Robinson 1996, 1). Yet racialized land ownership predates apartheid. As seen in this map from AJ Chistopher (1994 33), there is a striking correlation between the areas where non-white South Africans could own land in the 1913 and 1936 Natives Lands Acts, and apartheid-era bantustans.

Historical Map showing the extent of forced relocations (Image from Surplus Peoples Project, 1984. Reproduced with permission of Mission Basil 21)

This second map from the nonprofit Surplus Peoples Project (1984) documents the scale of forced dispossession and relocation into former bantustans: over 3.5 million non-white South Africans were forcibly relocated.

This second map from the nonprofit Surplus Peoples Project (1984) documents the scale of forced dispossession and relocation into former bantustans: over 3.5 million non-white South Africans were forcibly relocated.

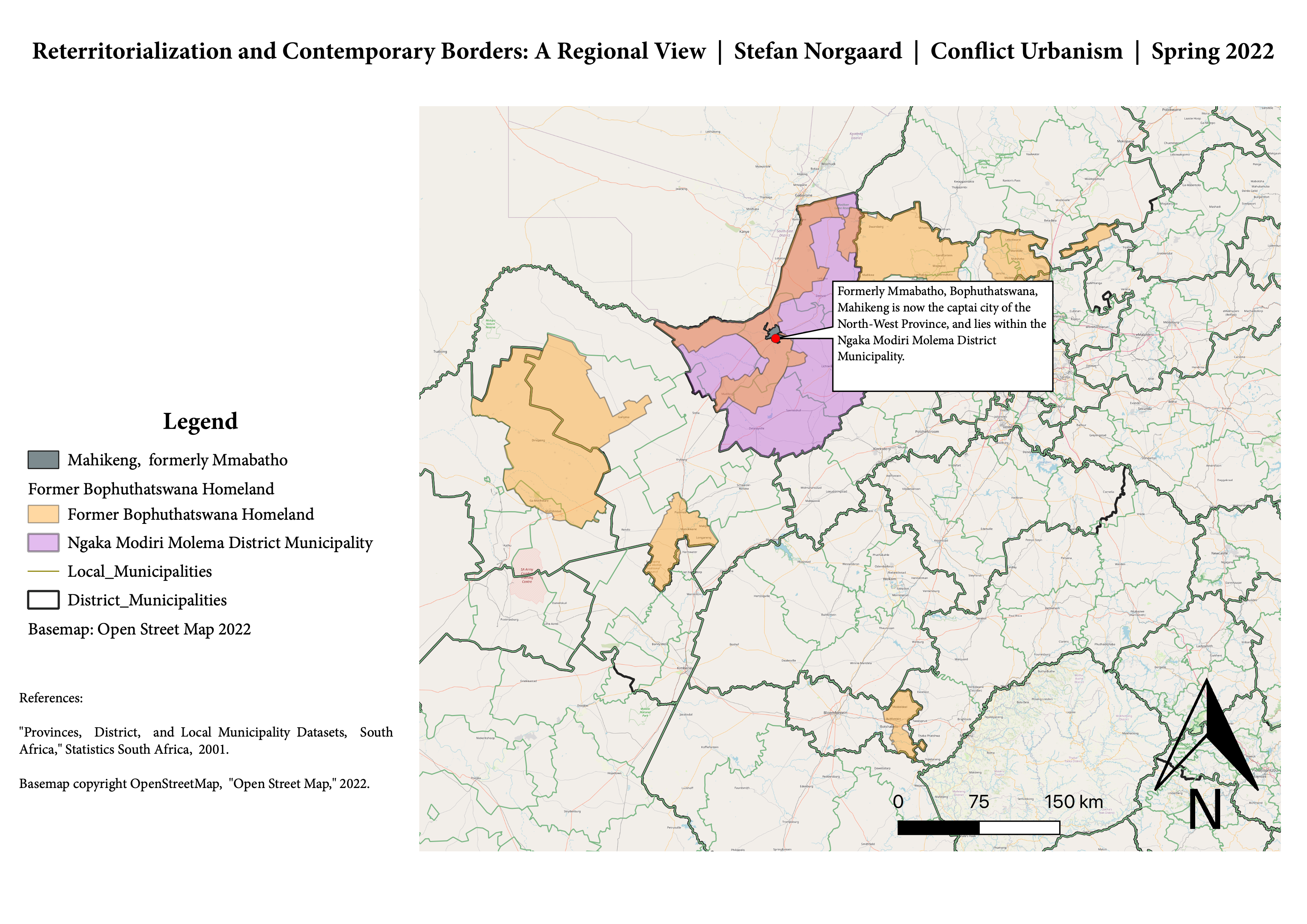

In the post-apartheid era, the status of citizenship and land have changed once more. A deterritorialization of homeland boundaries in the 1990s is now marked by a wall-to-wall system of provinces and district and local municipalities. Yet as Mpofu-Walsh (2021) has argued, aparthied persists across South African society, which remains by many measures the world’s most unequal.

In the post-apartheid era, the status of citizenship and land have changed once more. A deterritorialization of homeland boundaries in the 1990s is now marked by a wall-to-wall system of provinces and district and local municipalities. Yet as Mpofu-Walsh (2021) has argued, aparthied persists across South African society, which remains by many measures the world’s most unequal.

Regional Scale

The narrowing of attention to the regional scale highlights the interactions between land and border regimes with the realities “on the ground,” blurring the clarity that national boundaries often claim to have.

Still often drawn at a distance, the regional administrative boundaries, though, speak to the element of proximity and its significance in realizing acts of territorialization. Palestinian subjects and British authorities of the subdivision scale had a different relationship with each other than Palestinians had to the national-level authorities (Robinson 2013; Seikaly 2016). While the national territorialization Mandate and Israeli scales saw divergences of boundaries, looking at this regional scale, we begin to see some convergences. Within the contemporary borders of Israel, the names and relative sizes of the administrative boundaries remained the same.

In South Africa, a regional-scale map highlights the original creation and borders of the homeland, or bantustan, known as Bophuthatswana. The map shows its territorial non-contiguity, making the space de facto completely dependent on then-apartheid South Africa. This territorial separation meant countless borders and checkpoints in the apartheid era. The master-planned capital city, Mmabatho, was reintegrated into the Republic of South Africa in the 1990s.

Municipal Scale

Continuing to scope the focus, turning our attention to the municipal and neighborhood scale, this more situated view complicates the clear lines of the national scale. State-based efforts become incredibly murky as the lingering afterlives of past territorializations intertwine with community efforts, blurring the dividing lines. In their re-territorializing, communities strategically deploy the repurposement and use of space, spatial abandonment, and continuity with past land use to assert their claims to and sense of belonging in these contested spaces.

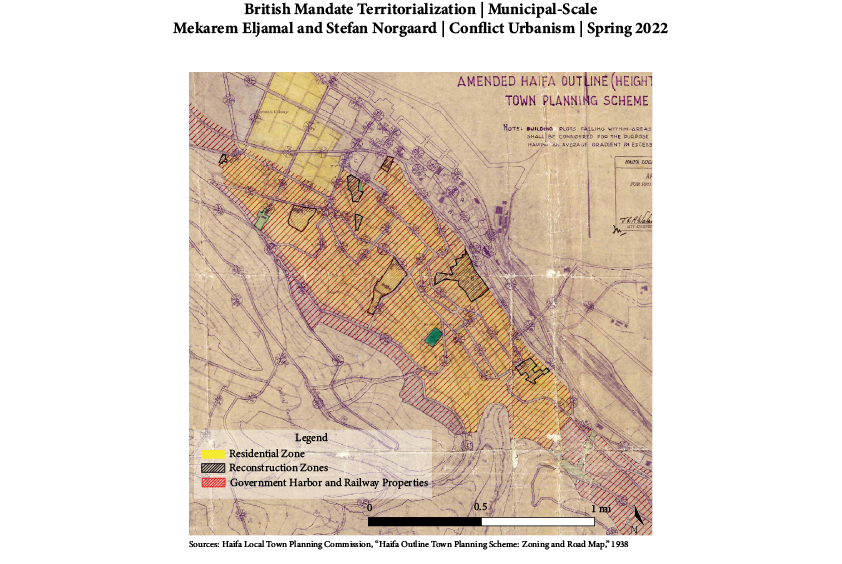

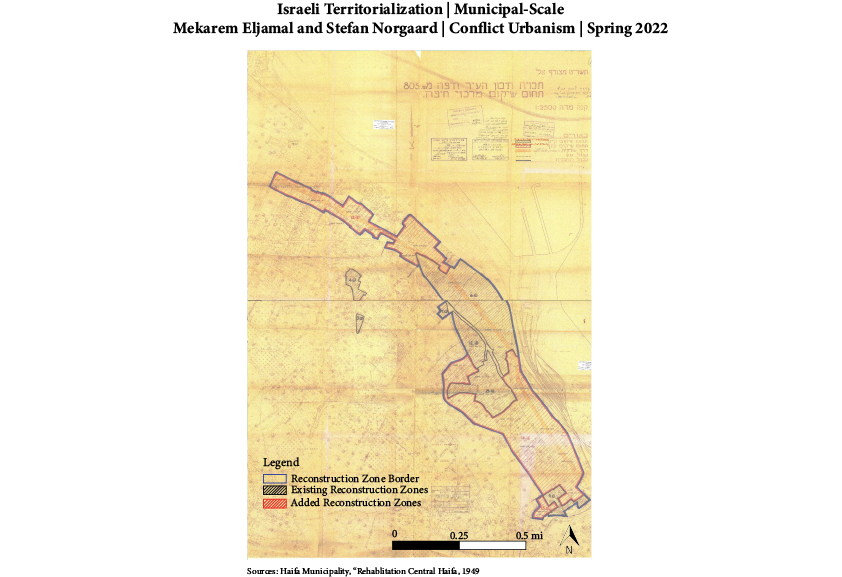

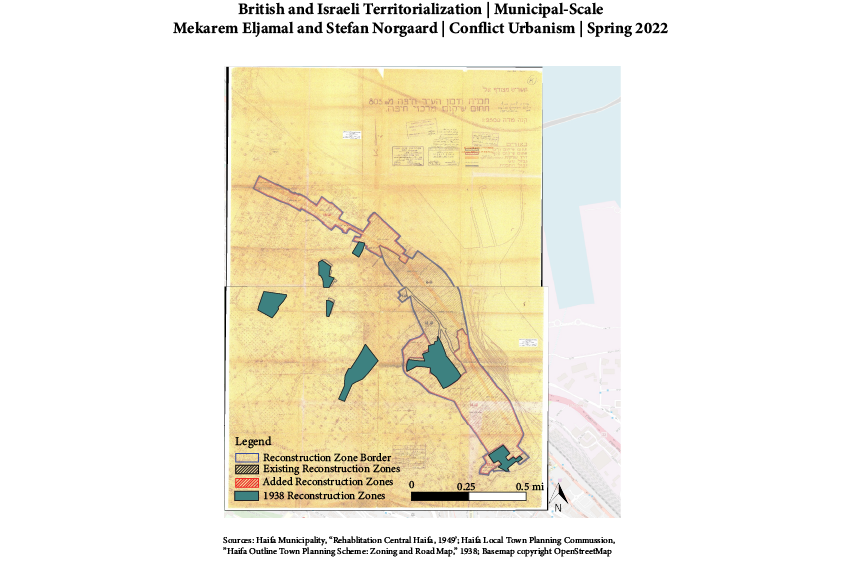

At the more fine-grained scale of the neighborhood level, depicted by these town planning schemes and redevelopment plans, we see continuity between regimes in the municipal approach to territorialization. Set nearly a decade apart, both the Israeli and Mandate governments devoted significant energy and attention to nearly the same areas, as evidenced by the overlapping and proximate redevelopment zones, each relying on material redevelopment to inscribe specific identities and meaning on the space. While redevelopment schemes under the Mandate period fit with more generic “ordering” priorities, such as straightening and widening roads, the redevelopment seen in the Israeli scheme is contextualized with the 1948 Operation Shikmona, which left the Lower City and adjacent neighborhoods devastated. Such destruction opened the opportunity for the new Haifa municipality to redefine the area, erasing and appropriating histories inscribed into the urban fabric. As we will see shortly, though, the success of such a plan is not as clear as the lines of a scheme.

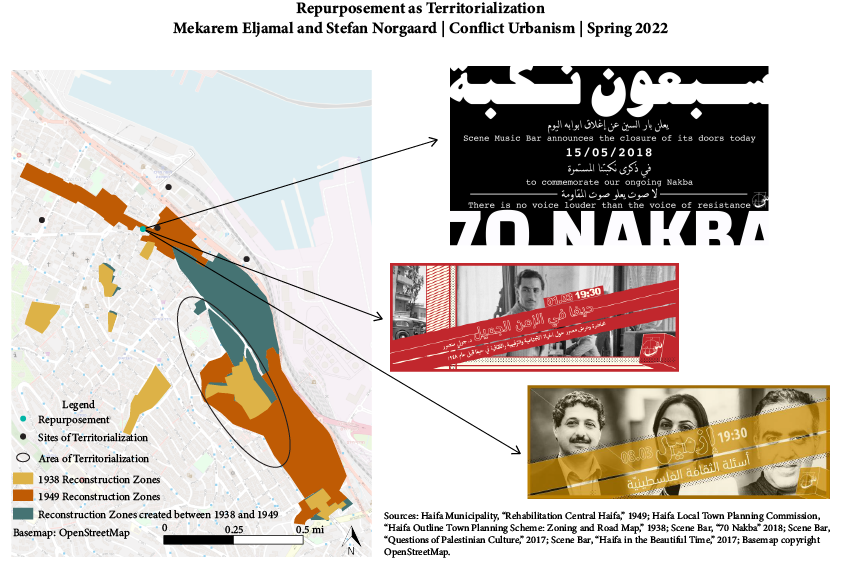

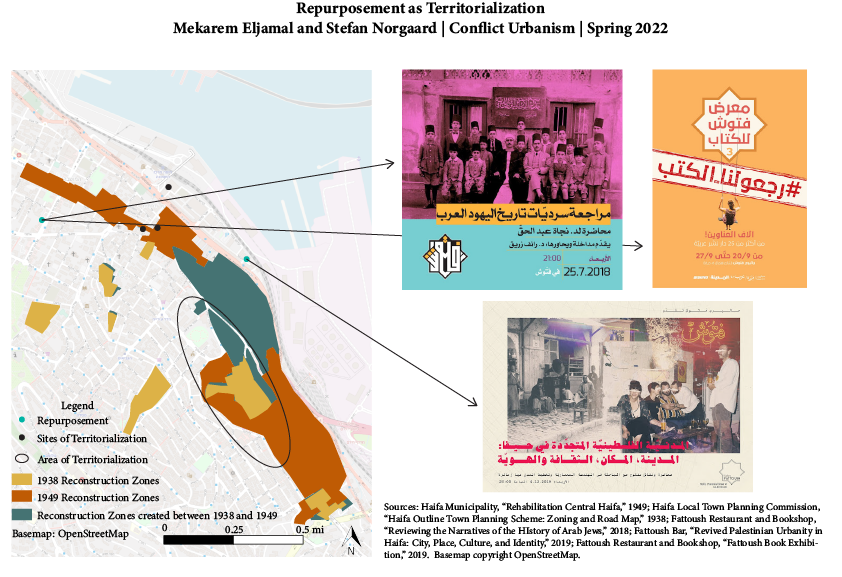

Such state-level interventions territorializing Haifa are then contrasted with Palestinian modes of territorialization, reclaiming the spaces that have been deemed blighted or in need of correction by governing regimes. In making claims upon space, territorialization techniques include repurposement and targeted engagement with abandonment.

While Scene Bar and Fattoush are only two examples of intentional repurposement of spaces within areas historically designated for redevelopment, these two businesses have asserted Palestinian presence through buiness practices, such as closing to commemorate the explusion of Palestinians from their homes in 1948, as well as programming decisions. Their programming centers Palestinian voices and concerns, as seen through the flyers advertising lectures on Palestinian urbanity in Haifa, quesitons of Palesitnian culture, and a book exhibition dedicated to Palestinian and Arab publications. Coupling the content of these programs with their intentional advertisement in only Arabic or Arabic and English, Hebrew’s absence is palpable and clearly points to whom these businesses prioritize.

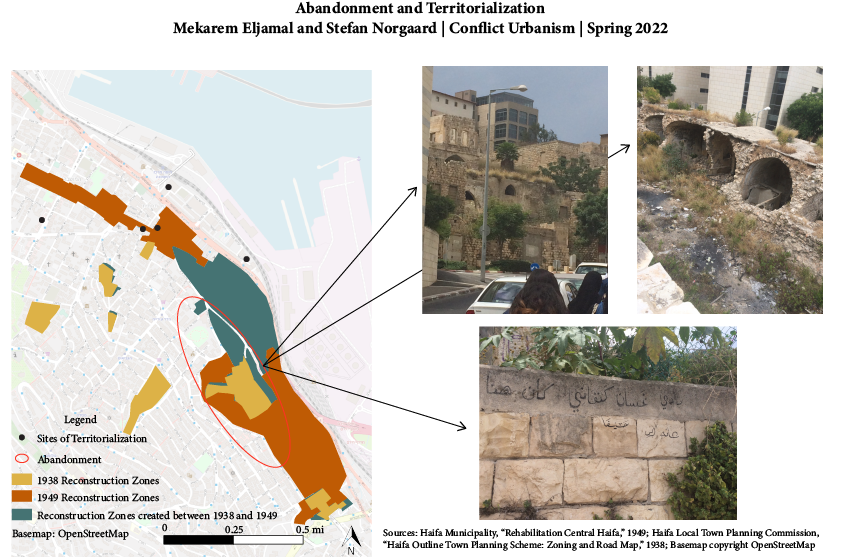

Finding the language to describe the destroyed homes, forced into abandonment by violence and networks of laws forbidding Palestinian returns, dotting the landscape of Wadi Salib is difficult. Understanding the many layers of destruction and implications of its maintained visibility, Stoler’s (2008, 196) language of ruination speaks to how these sites serve as spaces of territorialization. The engagement with the ruination of Wadi Salib is how the destroyed homes turn into locales of territorialization. Capturing the idea of ruination as simultaneously “an actu perpetrated, a condition to which one is subject, and a cause of loss,” the tours, such as the one during which the above photos were captured, led by Palestinian organizations through these sites and the graffitti asserting continued Palesitnian presence (2008, 195).

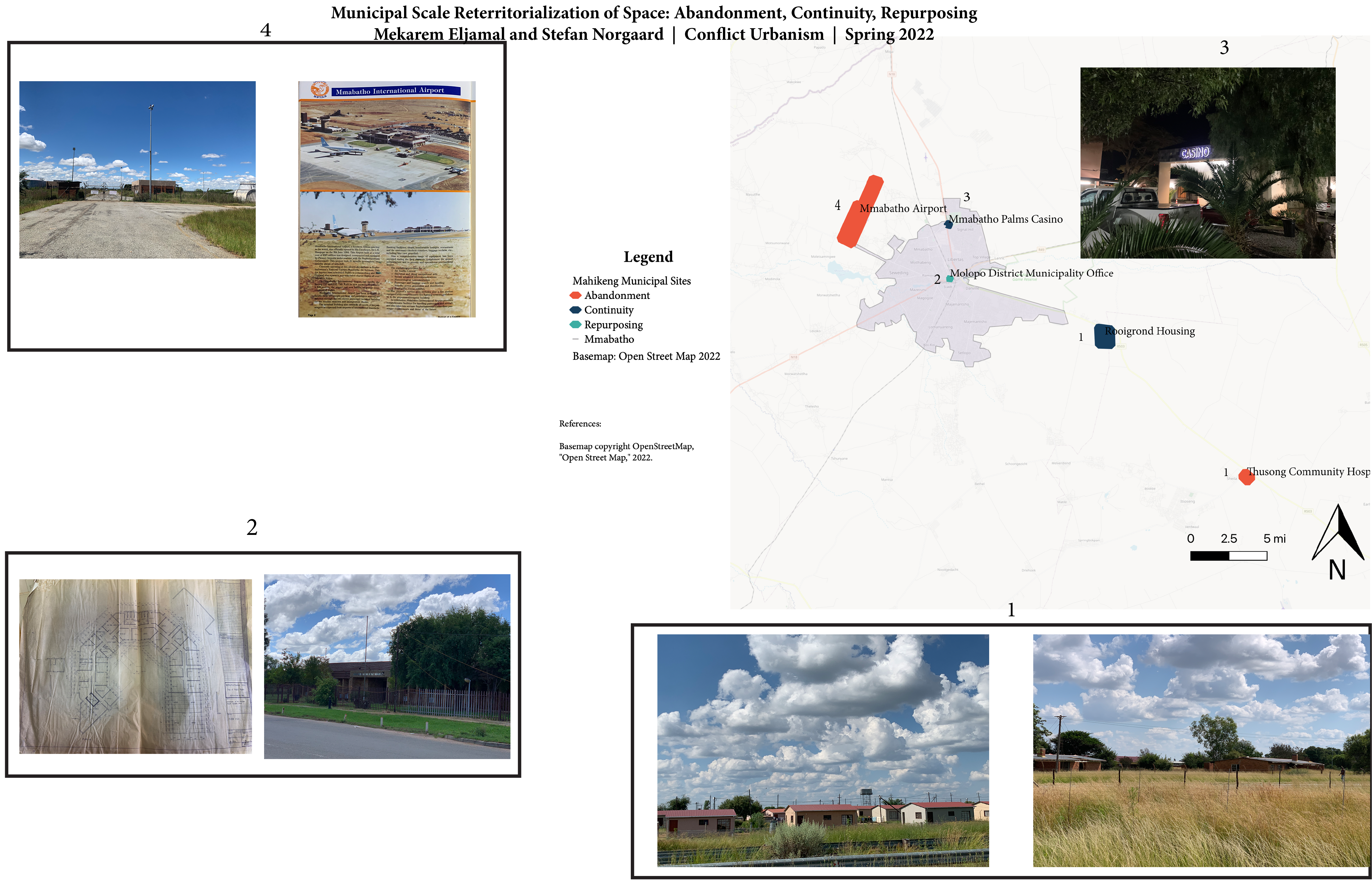

In Mahikeng (formerly the pre-planned capital city of Mmabatho), municipal-scale maps convery the city’s 1970s’ master-plan, which exists both alongside and in contrast to city spaces today. The apartheid and post-apartheid state and residents alike have drawn on territorialization techniques of abandonment, repurposement, and continuity in locally situated ways that are hard to predict.

As seen above, the Mmabatho airport and Thusong Community Hospital both now sit vacant in the North-West Province’s landscape, remnants in the built environment of what once was. By contrast, what was original planned as the Bophuthatswana Molopo District Governor’s Office has been repurposed as the ANC’s Ngaka Modiri Molema District Municipality Office. Yet we see continuity in residential zones. The Rooigrond housing neighborhood remains today a site of dwelling. Its matchbox-size homes were built in the wake of massive apartheid-era forced relocation in the creation of the homelands. Likewise, Mmabatho Palms Casino, a luxury casino that thrived in the days when apartheid South Africa forbid gambling, remains an anchor business in Mahikeng today.

As seen above, the Mmabatho airport and Thusong Community Hospital both now sit vacant in the North-West Province’s landscape, remnants in the built environment of what once was. By contrast, what was original planned as the Bophuthatswana Molopo District Governor’s Office has been repurposed as the ANC’s Ngaka Modiri Molema District Municipality Office. Yet we see continuity in residential zones. The Rooigrond housing neighborhood remains today a site of dwelling. Its matchbox-size homes were built in the wake of massive apartheid-era forced relocation in the creation of the homelands. Likewise, Mmabatho Palms Casino, a luxury casino that thrived in the days when apartheid South Africa forbid gambling, remains an anchor business in Mahikeng today.

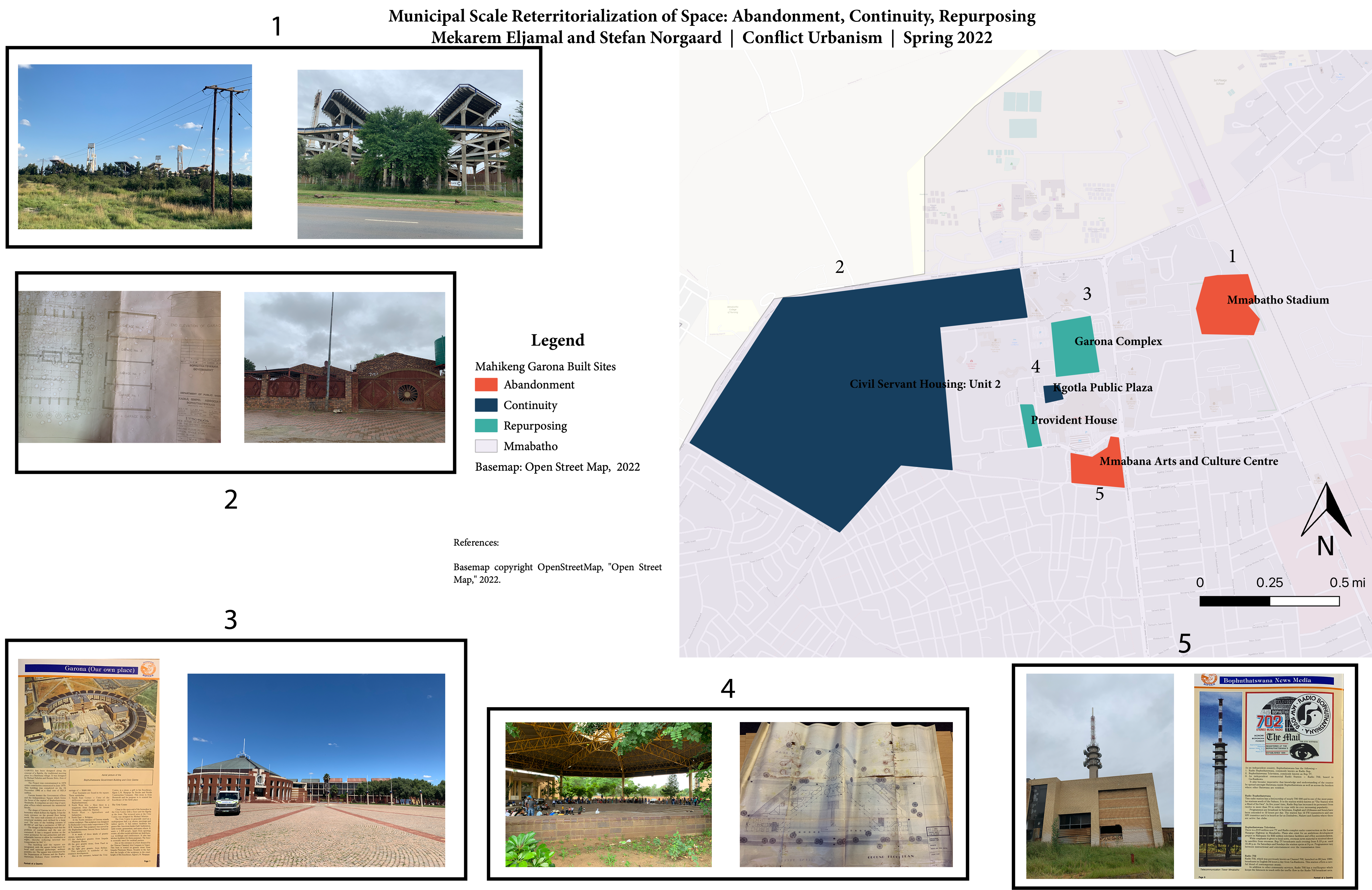

Zooming into the neighborhood level, we continue to see tactics of abandonment, repurposing, and continuity in practice. Sites like the massive Mmabatho Stadium and Mmabana Arts and Culture Complex now sit vacant. Designed by Israeli Architects Ilan Sharon and Israel Godowitz in the 1970s and 80s, they have a considerable archival history and footprint. By contrast, the Garona Complex was initially envisioned as a site for the national government of Bophuthatswana in the apartheid-era system of indirect rule and today it houses provincial-level government offices for the ANC-run North-West Province. Finally, we continue to see continuity when it comes to residential arrangements. Civil servant housing in the Mmabatho Unit 2 area (now Mahikeng, North-West) has remained continuously in use as housing for upper-middle class residents, and the Kgotla Plaza public space remains used dynamically by residents. This public space leverages Tswana architecture conceptions of public meeting grounds and has been a well-used public space across institutional moments.

Zooming into the neighborhood level, we continue to see tactics of abandonment, repurposing, and continuity in practice. Sites like the massive Mmabatho Stadium and Mmabana Arts and Culture Complex now sit vacant. Designed by Israeli Architects Ilan Sharon and Israel Godowitz in the 1970s and 80s, they have a considerable archival history and footprint. By contrast, the Garona Complex was initially envisioned as a site for the national government of Bophuthatswana in the apartheid-era system of indirect rule and today it houses provincial-level government offices for the ANC-run North-West Province. Finally, we continue to see continuity when it comes to residential arrangements. Civil servant housing in the Mmabatho Unit 2 area (now Mahikeng, North-West) has remained continuously in use as housing for upper-middle class residents, and the Kgotla Plaza public space remains used dynamically by residents. This public space leverages Tswana architecture conceptions of public meeting grounds and has been a well-used public space across institutional moments.

Maps grounded in local places show active efforts at territorial contestation by residents. Photographs, event programs, programs, and advertisements, alongside people repurposing or strategically re-using buildings, reveal active processes of infrapolitics and spatial reappropriation within the original built environments and architectures of national-level planning and territory schemes. The result is places marked by complex hybrid uses and functions.

Limitations

Our examination of territorialization is restricted to specific local places and should not be generalized beyond these localities. Moreover, as authors, our primary data collection has been limited to specific (and short) periods of time. Accordingly, our experiences of territorialization processes in action is partial, and to some degree impressionistic. Additionally, our work faces data limitations: both the Palestinian and South African context is marked by data embargoes, censorship, and historical or contemporary archival erasure. Nonetheless, we believe that focusing on territorialization as dynamic and contradictory processes enacted in places by residents and nation-states alike affords a new way to view maps and boundaries. We encourage researchers to further triangulate this hypothesis with residents in varied contexts.

Implications and Conclusion

Lessons for planners, architects, and scholars emerge from our focus on territorialization: spaces are iterative, with territorialization processes that are never complete with a single outcome. Rarely do places on-the-ground conform fully to abstract representations of space as shown on nation-level maps. Instead, places take on lives of their own in a complex amalgamation of states, institutions, and people. De- and re-territorialization processes are never seen within the purview of one actor’s vision. Outcomes are never static. As we take this longue durée approach to claiming space continuously, we see the lack of the control that institutions and states have in producing space. Local residents subvert and appropriate spaces to make places, while still working and existing with constraints (Creswell 1996). Our project draws on tools of mapping, jurisdiction, and boundary-making to show precisely how such tools are insufficient to understanding lived realities and constructions and reconstructions of place.

References

Spatial Data:

Basemap. 2022. Copyright Open Street Map. Accessed 15 March 2022. Under CC BY 3.0. Data by OpenStreetMap, open data licensed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) by the OpenStreetMap Foundation (OSMF).

Hijmans, Robert and University of California-Berkeley. 2015. “Boundary, Israel, 2015.” [shapefile]. UC Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. 2015. Accessed 20 March 2022. http://purl.stanford.edu/vq116mt9730.

Hijmans, Robert and University of California-Berkeley. 2015. “First-level Administrative Divisions, Israel, 2015.” [shapefile].UC Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Accessed 20 March 2022. http://purl.stanford.edu/ch107xc0728</idCredit>.

Ministry of Interior. 2008. “Gvulot Shiput.” [shapefile]. GIS Information System. Accessed 20 March 2022. https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/Guides/info-gis.

“Former Homelands.” 2022. Accessed courtesy of Fiona Drummond. Government of the Republic of South Africa, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Accessed 25 March 2022. http://daffgis.daff.gov.za/portal/home/group.html?id=3eee49d53eb045dc885bdb883fb5504b&focus=layers&sortField=numviews&sortOrder=desc.

Statistics South Africa (SSA). 2010. “Provinces, District, and Local Municipality” Datasets. Presentation Form vector digital data of the South Africa Geography collection. Accessed 15 March 2022. Available online at: http://mapserver2.statssa.gov.za/geographywebsite/.

Primary Visual Sources:

“1913 and 1936 Natives’ Land Acts.” 1989. The Human Awareness Programme of the Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA). Exhibits D5 and D6. Accessed 20 April 2022. Available at https://afra.co.za/resources/, and https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnx0c2hpbnRzaGFpbnRyYW5ldHxneDo0ZmFlMDRkNDQwN2MzOWQx.

“A Land Divided Against Itself: A Map of South Africa Showing the African Homelands and Some of the Mass Removals of People which have Taken Place.” 1977. Mission Basel 21. Ref. number: KARVAR-31.135. Accessed 23 February 2022. Available online at: https://www.bmarchives.org/items/show/100204688#.

Haifa Local Town Planning Commission. 1938. “Haifa Outline Town Planning Scheme: Zoning and Road Map.” Haifa Engineering Archive.

Haifa Municipality. 1949. “Rehabilitation Central Haifa.” Haifa Engineering Archive.

Survey of Palestine. 1936. “Palestine Administration Map.” Eran Laor Collection of Maps. National Library of Israel. Ref. number: Pal 1193. Accessed 15 April. Available online at: https://www.nli.org.il/en/maps/NNL_ALEPH002367940/NLI#$FL13746855

United Nations. 1947. “Palestine Plan on Partition with Economic Union.” London. Eran Laor Collection of Maps. National Library of Israel. Ref. number: Pal 1107.1. Accessed 15 April 2022. Available online at: https://www.nli.org.il/en/maps/NNL_MAPS_JER002612446/NLI#$FL25570438

Secondary Sources:

Clarno, Andy. 2017. Neoliberal Apartheid: Palestine/Israel and South Africa after 1994. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Creswell, Tim. 1996. In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology, and Transgression. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public.” Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 4–31.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1974. The Production of Space. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1996. “The Other Face of Tribalism: Peasant Movements in Equatorial Africa.” In: Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, 183–217. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mpofu-Walsh, Sizwe. 2021. The New Apartheid. Cape Town: Tafelberg Uitgewers BPK.

Robinson, Jennifer. 1996. The Power of Apartheid: State, Power, and Space in South African Cities. Johannesburg: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Robinson, Shira. 2013. Citizen Strangers: Palestinians and the Birth of Israel’s Liberal Settler State Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Scott, James C. 2012. “Infrapolitics and Mobilizations: A Response by James C. Scott.” Revue Française d’Études Américaines 1(131): 112–117.

Seikaly, Sherene. 2016. Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Simone, Abdoumaliq. 2004. “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg.” Public Culture 16(3): 407-429.

Stoler, Ann. 2008. “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination.” Cultural Anthropology 23(2): 191-219.