The New York City Subway: Invisibility, Crisis, Material, Fantasy

New York City is the Subway: the Subway is New York City

The New York City subway system at the time of its conception in the late 19th century, began as a fantasy of urban life that would grow to become one of the largest and most ambitious infrastructure projects in history. As the subway system expanded, the city grew with it, and today the fantasies of urban life that the subway enabled are deeply intertwined with the physical growth, economic development and cultural imaginaries of the places it connects.

In many ways, large infrastructural systems like the subway represent a collective fantasy of the city - a shared physical apparatus that shapes individual routines, desires and identities. The subway is what enables the vision of New York City as “The Greatest City on Earth” - “The City that Never Sleeps.” From the day that the first underground line opened in 1904, the subway system has run 24/7, setting the terms for social and economic life in the city.

This collective fantasy is enabled by the material infrastructural components that make up the subway system - the train cars, tracks, signaling systems, control rooms as well as the train operators, maintenance workers and MTA officials that operate them. When infrastructure operates smoothly, these material and human infrastructures remain invisible, and we are able to cast onto them our own fantasies and desires, seeing them only as a means to our own ends, causing the material conditions of the system to remain invisible until moments of crisis or disruption.

Framing

This project studies the New York City subway system through two analytical frameworks: invisibility/crisis and material/fantasy.

INVISIBILITY/CRISIS The project identifies three recent moments of crisis - Hurricane Sandy (2012), the Summer of Hell (2017) and the Covid-19 Pandemic (2020) - when the materiality of the system was rendered visible to the public. Through these crises, I identify crucial material components and human infrastructures that were exposed by the disruptions and in the post-crisis recovery process.

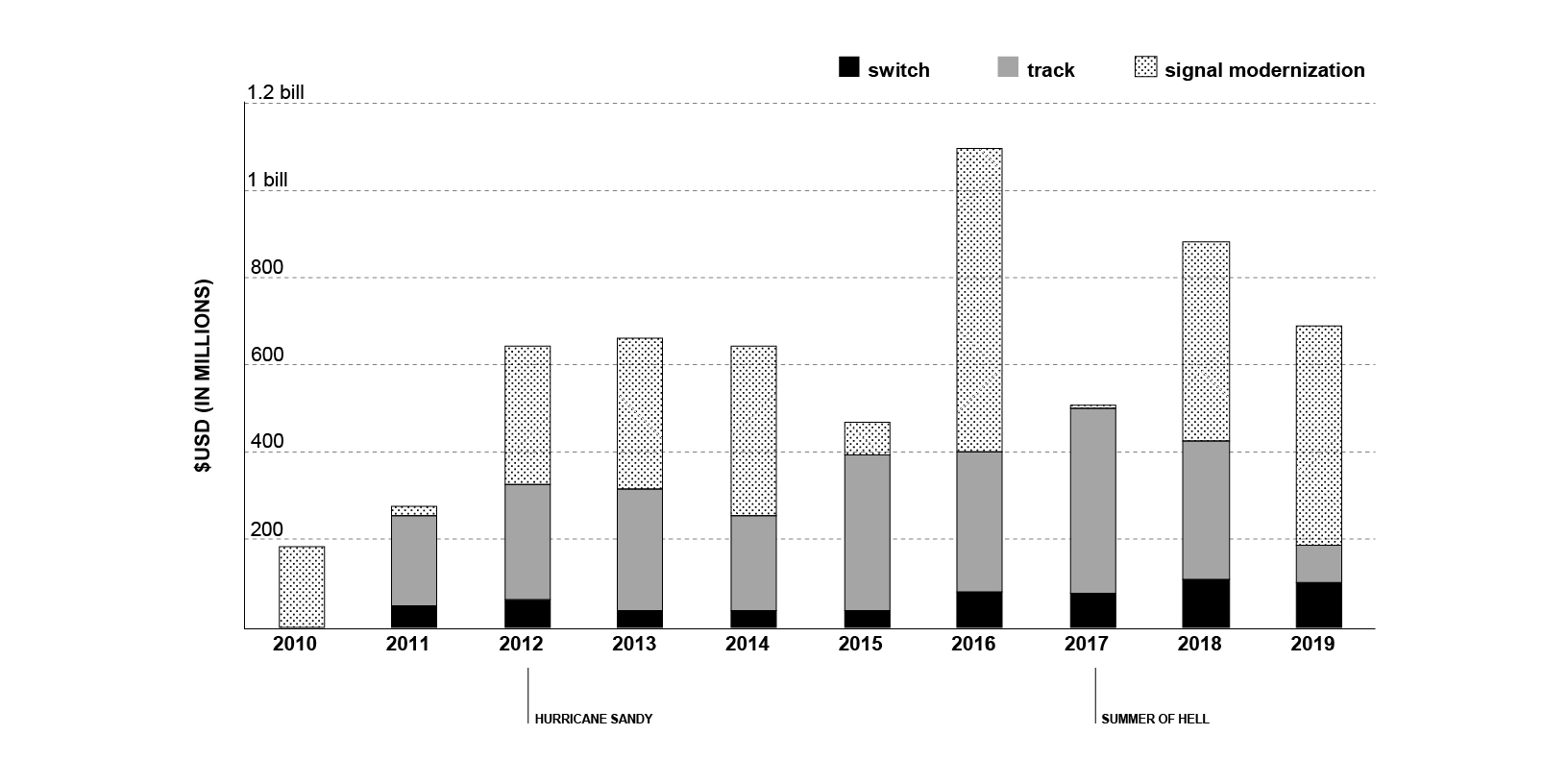

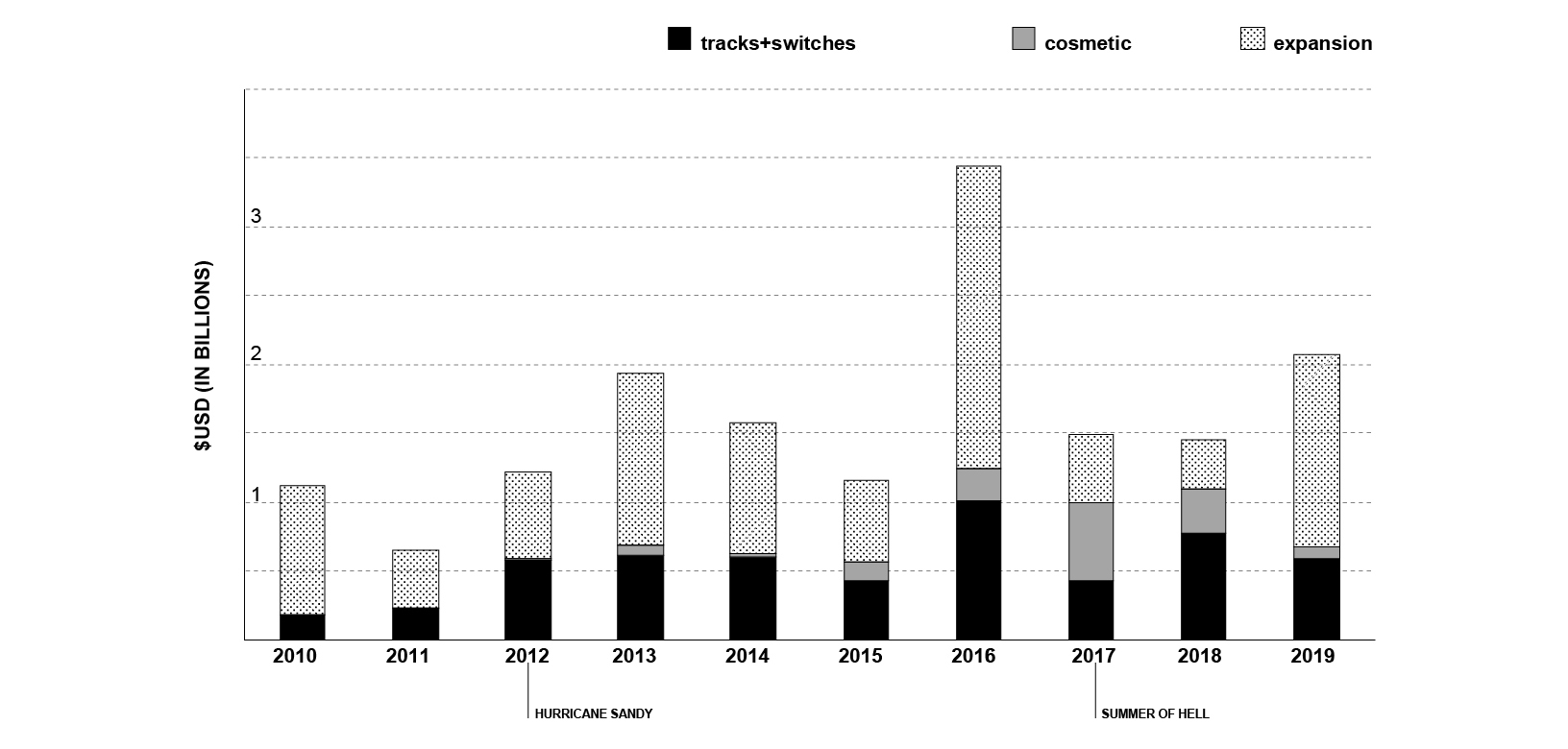

MATERIALITY/FANTASY By tracking specific components and types of repairs through the MTA’s capital plans, we are able to see patterns in the MTA’s prioritization of material investments. When seen through the lens of two fantasies, 1 our collective fantasy of the 24/7 transit system and 2 Governor Cuomo’s fantasy of the Second Avenue Subway, the MTA’s material investments demonstrate how the materiality of the subway is the result of a negotiation of competing social and political fantasies.

These investigations are particularly urgent today as the subway system is in a state of “existential crisis,” as stated in a recent report by the New York State Comptroller, and as infrastructure re-enters public political discourse in the US with a $1 trillion dollar infrastructure bill passed in the senate in November 2021.

THE 24/7 SUBWAY, A COLLECTIVE FANTASY

INVISIBILITY: “A DAILY MAGIC TRICK”

Before Hurricane Sandy, the 24/7 subway system was a collective fantasy of “the City that Never Sleeps.” A profile in the New York Times calls it: “a daily magic trick: It brings people together, but it also spreads people out. It is this paradox — these constant expansions and contractions, like a beating heart — that keep the human capital flowing and the city growing. New York’s subway has no zones and no hours of operation. It connects rich and poor neighborhoods alike. The subway has never been segregated. It is always open, and the fare is always the same no matter how far you need to go. In New York, movement — anywhere, anytime — is a right.” As long as the subway reliably performed its daily magic trick, people paid little attention to the material condition of the stations, tunnels and tracks that make up the system. In fact, its invisibility is a part of the trick.

CRISIS: HURRICANE SANDY

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused unprecedented damage to the system - every tunnel under the East River connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn was flooded and stations in lower Manhattan were filled “track to ceiling” with water. In the Rockaways, above ground tracks were submerged, washed away or covered in debris. When the MTA was forced to shut down the subway after Hurricane Sandy to evaluate and repair the damage, the collective fantasy of the 24/7 transit system was disrupted and the material components - the tracks, switches, controls and power cables - that keep the subways running were unveiled to the public in apocalyptic photos of flooded and grime coated tunnels. The MTA started work the morning after the storm and quickly announced plans to bring the system back to “working order.” Stations and tunnels were meticulously cleared of water and debris, and tunnels that were underwater for days were cleaned and budgeted for 100 million dollar restoration projects.

MATERIAL LOGICS: FIXED BLOCK VS CBTC

The damage to the system was exacerbated by the material makeup and mechanical logics of the signaling system that runs the subway system. Many lines still rely on the same fixed block signaling system that was installed when the subway first opened in the early 20th century. Fixed block signaling systems use thousands of trackside components to operate trains, making the system more vulnerable to flood damage and making the repair and maintenance of the system a difficult and complicated process.

Before Hurricane Sandy, another type of signaling had been implemented on the L train line, which was used as a pilot program for Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) , the industry standard in more recently constructed mass transit systems. By using radio signals to communicate between cars and control towers and by consolidating controls in above ground control centers, the most vital parts of the system would be less exposed to flooding and the process of maintenance and repair would be simpler and less costly. Additionally, many of CBTC’s components, such as transponders are designed to be completely waterproof, or removable in a flooding event. However, although CBTC allows for fewer trackside signals and more efficient and automated operation of trains, implementing CBTC requires large stretches of tunnel to be shut down in order to install new material components trackside.

FANTASY: RESTORING THE SYSTEM TO “WORKING ORDER”

Hurricane Sandy unveiled and problematized a signaling system that had been invisible and taken for granted. In the post-Sandy recovery process, despite the new urgency of replacing fixed block signals with newer technologies that would have allowed the system to become more resilient, the importance of the 24/7 subway system to the daily routines and livelihoods of New Yorkers caused the MTA to focus on restoring the system to “working order” as soon as possible, rather than on disruptive systemwide signal modernization plans.

The flurry of activity in the weeks and months following Sandy was focused on meticulously repairing or replacing the most damaged material components to restore service as fast as possible. The remarkable speed of the “recovery” was another magic trick that hid the true material damage and the intensive labor that brought the system back to working order. Limited service returned on November 1st to uptown Manhattan and inland areas in Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx, only three days after the storm. In the next week, connections to Brooklyn were restored as the tubes under the east river were pumped and repaired. As service resumed, the social and economic life of the city returned, but the corrosive effects of the salt water continued to work their damage on the thousands of complex individually wired mechanical parts of decades old track and signal components.

CRISIS: SUMMER OF HELL

The consequences of the subway’s return to invisibility revealed themselves during the Summer of Hell in 2017, when the subway’s material problems became painfully apparent to daily commuters. An F train was trapped in a tunnel for an hour without air conditioning, a Q train derailed in Brooklyn, a track fire on the A train injured 9, and countless delays caused dangerously crowded conditions on platforms and subway cars.

Public outrage forced the MTA to act - on June 29th, 2017, then governor Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency for the NYC subway system. Shortly afterwards, the MTA implemented the $836 million Subway Action Plan (SAP) which managed to decrease weekday incients delaying more than 50 trains by 40% between 2017 and 2019, by focusing on the stabilization of the system through stop gap measures such as “rail grinding” to reduce rail defects, replacing old track with continuous welded rail, and cleaning tracks with vacuum trains, and the manual cleaning of drains and vents, etc.

The Summer of Hell shows that the concept of returning the subway to “working order” is itself a contested fantasy - a threshold that depends on an individual’s tolerance for delay and the delicate balance between material degradation and the maintenance and repair work that keeps it functional. The invisibility of the damaged track and signal components after the subway was returned to “working order” created the material, social and political conditions for the crises that took place during the Summer of Hell. The subway system crossed over into crisis when the disruptions to people’s daily routines brought the materiality of infrastructure back out of invisibility.

MATERIAL ASSEMBLAGE: COUNTDOWN CLOCKS

The subway’s track and signaling components are material assemblages that are subject to the contested politics of the MTA’s governance structure. As a public benefits corporation that operates the New York City subway and bus systems, as well as the Long Island Rail Road and the Metro North, the MTA is run by board members elected by the state governor and recommended by the New York City mayor and four upstate counties. This assemblage of local and state powers is a reflection of the MTA’s participation in a larger transit system that politically, financially and physically connects New York City to many upstate counties. Accordingly, the political, financial and public will to maintain and upgrade the system is pushed and pulled by a network of state and local forces.

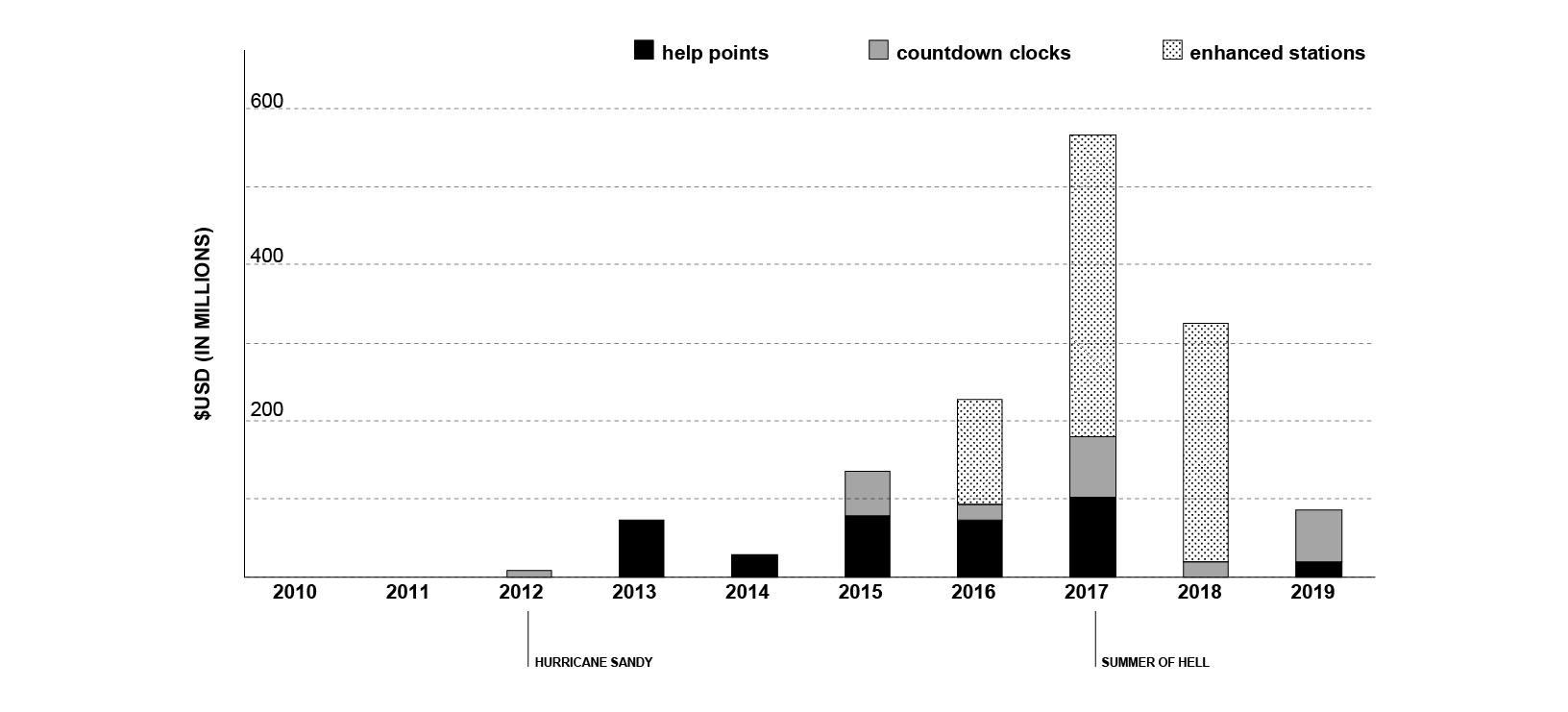

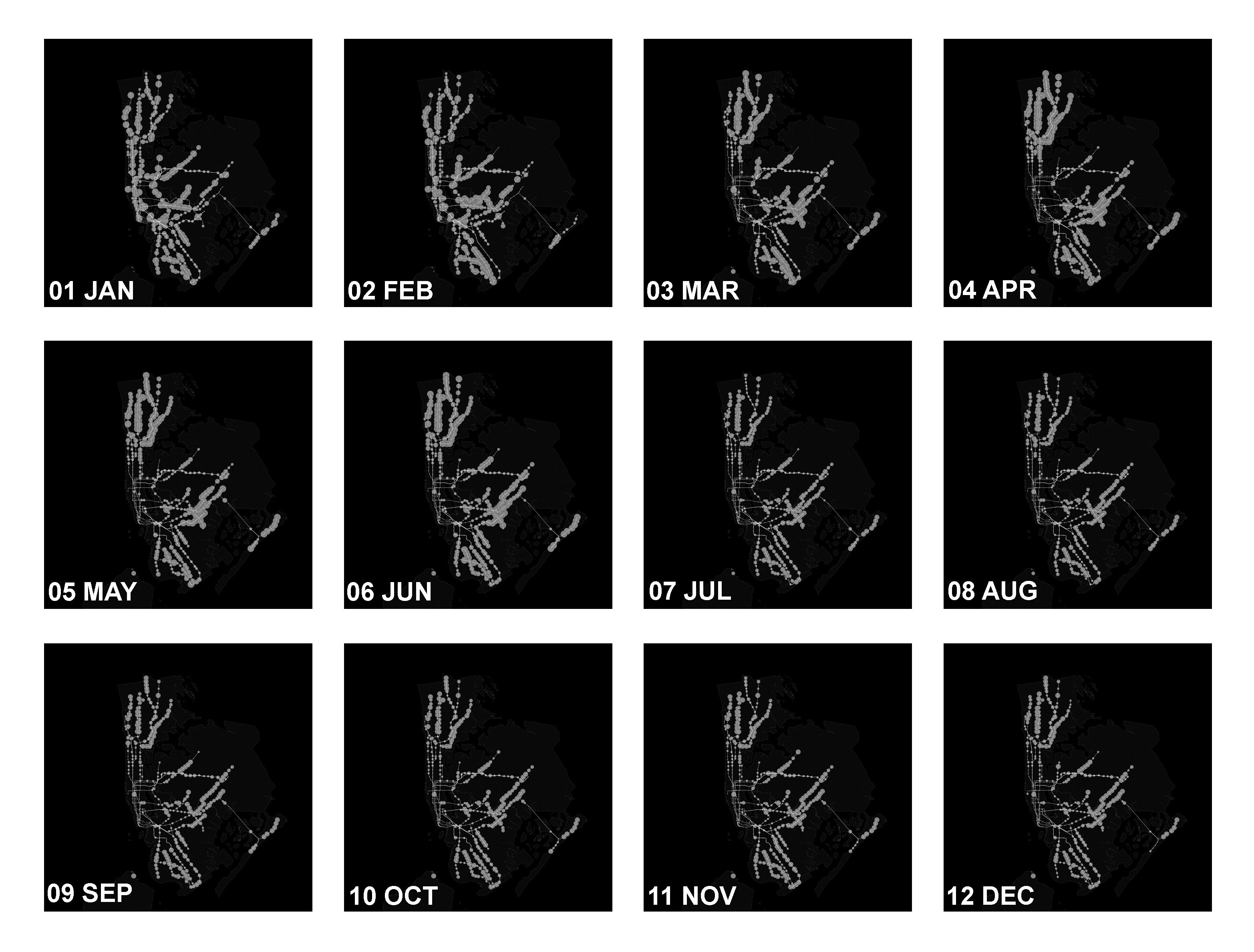

These socio-political dynamics shape the MTA’s logics of repair and maintenance. While track and signal modernization was performed surgically, if at all, highly visible cosmetic repairs to stations (which can be performed without disrupting subway service) were done system wide. The map on the left shows the locations from the 2015-2019 MTA capital program of signal and track modernization projects, while the map on the right shows the locations of cosmetic repairs.

The most iconic of these cosmetic repairs is the addition of countdown clocks to all station platforms. The countdown clocks, which were first installed on platforms serviced by lines using the CBTC signaling system represented a significant change in the material logics of how the subway is operated. CBTC countdown clocks display arrival times based on the exact location of trains identified and transmitted through radio transmitters installed along the track and on train cars.

On the other hand, countdown clocks connected to the ATS signaling system display arrival times based on digitized data from the fixed block signaling infrastructure that indicates which sections of track are occupied by trains. These arrival times are estimates based on the time it takes trains moving at average speeds to traverse a certain number of track “blocks.” However, as real signal and track modernization stalled, riders questioned why only certain platforms had countdown clocks, and as a result of a customer driven campaign, the MTA promised to deliver countdown clocks to all subway platforms by 2017.

Because the collective fantasy of the 24/7 subway takes for granted and renders invisible crucial track and signaling systems, as well as the contested political processes that affect the MTA’s budgetary decisions, countdown clocks were delivered, as promised, to all stations by 2017, but without the crucial track and signal repairs that the CBTC and ATS systems were meant to address.

THE SECOND AVENUE SUBWAY, CUOMO’S FANTASY

The Second Avenue Subway project was first proposed in 1929 as an ambitious extension of the Second Avenue line to connect Houston Street in lower Manhattan to the Bronx. However, multiple financial and political setbacks interrupted its progress and the construction started on two new stations north of the line’s 63rd street terminus in 2007. Despite the greatly diminished scope of the project, the Second Avenue Subway was sold to the public as a fantasy of modernity. For Governor Cuomo, the second avenue subway represented a different fantasy - one that would bring him political prestige as a Robert Moses of the 21st century, the governor who “got it done.” Enacted through expensive and highly publicized network expansion projects like the second avenue subway extension, Cuomo’s fantasy of the subway was a vision of what these highly visible infrastructural projects could do for his political legacy, built into the very material fabric of the city.

CRISIS: CUOMO’S SUMMER OF HELL

The Summer of Hell can also be seen as the result of Cuomo’s fantasy as well as the product of a governance structure that allowed the fantasy of one governor to draw focus away from other crucial system-wide repairs. In the case of the Second Avenue Subway, Cuomo held weekly meetings and made regular site visits to apply pressure on MTA workers and officials and to ensure the project’s completion by his December 2016 deadline. As the deadline approached, routine tests and inspections were canceled and the “best and brightest” MTA workers were pulled from their positions elsewhere in the system to work on the Second Avenue Subway project.

Cuomo’s heavy handed involvement in the Second Avenue Subway project mirrors the outsized role the state governor has on the MTA’s administration. The prioritization of the second avenue subway came at the cost of both the daily maintenance work that keeps the system in working order as well as the signal modernization work that would have helped the system avoid or better deal with the cascading crises of the Summer of Hell.

MATERIAL: HUMAN INFRASTRUCTURE

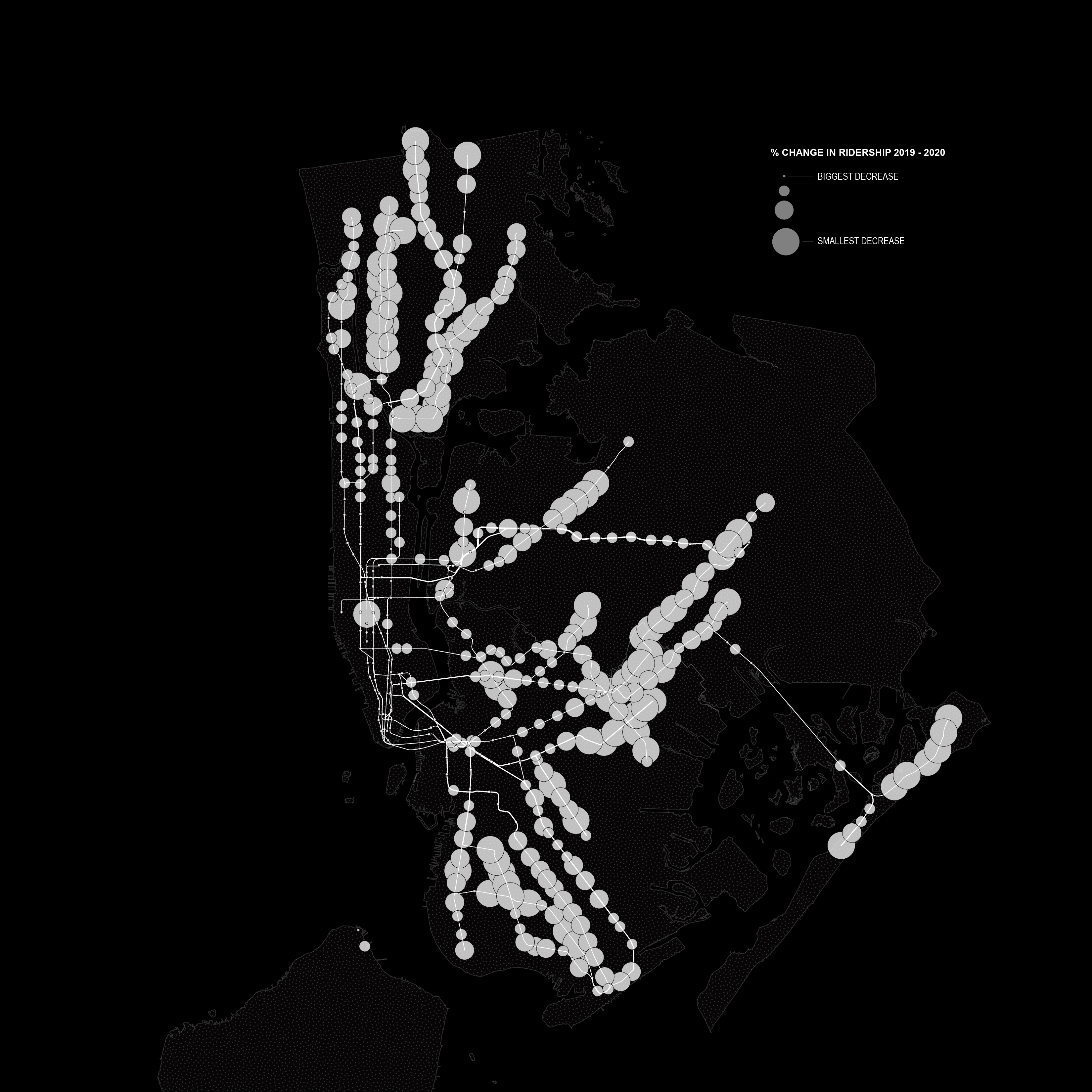

Crises that disrupt the subway system have unequal effects across the population of New York City. For some, disruptions are minor inconveniences, but many others rely on the subway for their livelihoods. In March 2020, Covid-19 ended the collective fantasy of the 24/7 subway for everyone. For the first time in its history, the subway system shut down overnight for disinfection and to accommodate staffing shortages and decreasing ridership in the wake of a citywide lockdown and rising Covid cases. Stations throughout the system saw a sharp decrease in ridership.

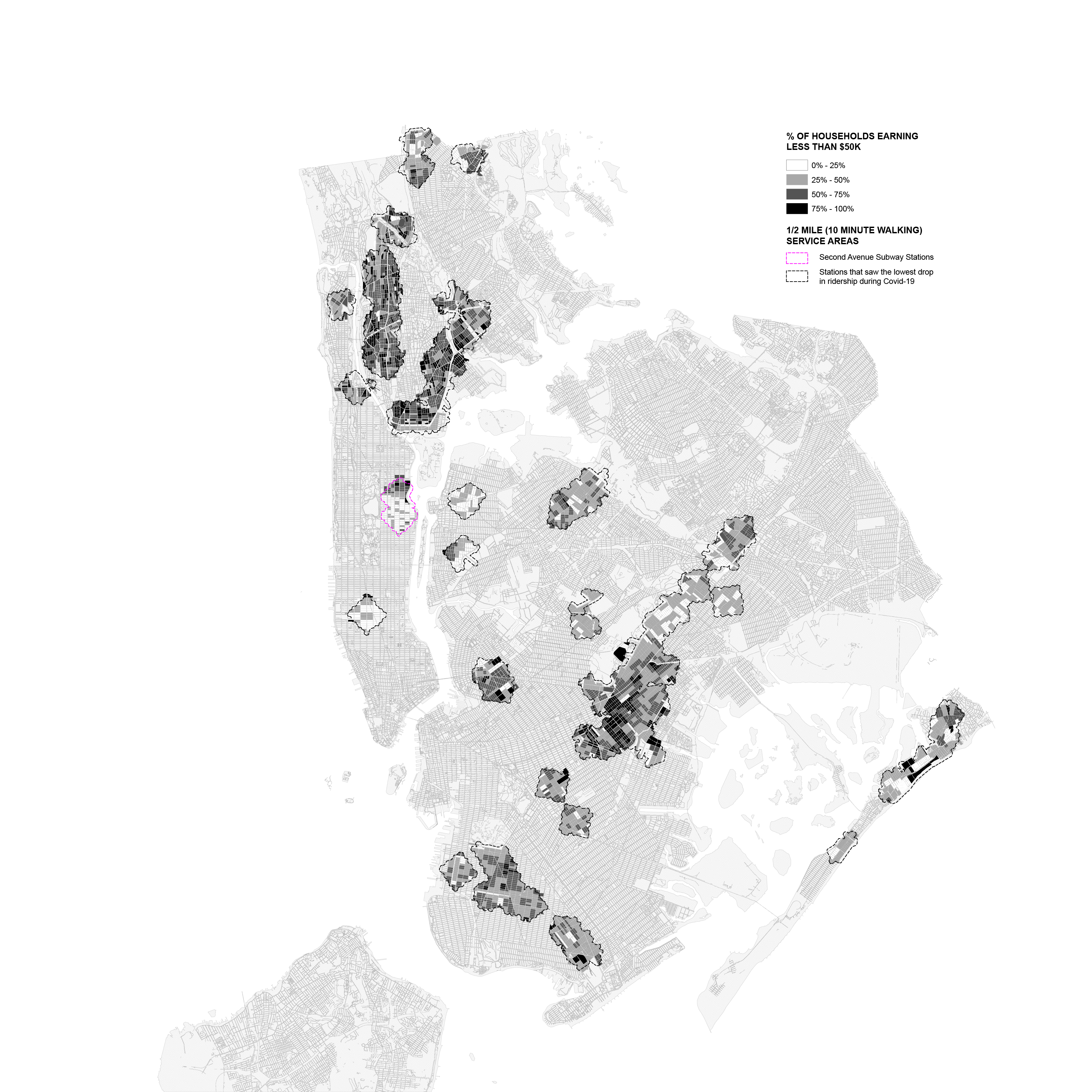

The stations that saw the least change in ridership serve populations that are most reliant on the subway system and are therefore least able to tolerate disruptions or delays to the system - the “essential workers” who rode the subway to work, despite the increased risk of illness and a citywide lockdown. Comparing the demographic makeup of the census blocks 10 min walking distance from the stations that are most reliant on the subway to the demographic makeup of the blocks surrounding the two new stations of the Second Avenue line shows how unevenly the MTA’s material investments across the population of the city.

Bibliography

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs, 28(3), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321 Castells, M. (2020). “Space of Flows, Space of Places: Materials for a Theory of Urbanism in the Information Age.” In The City Reader (7th ed.). Routledge. Dwyer, J. (2020, February 3). How a Clash of Egos Became Bigger Than Fixing the Subway. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/03/nyregion/cuomo-andy-byford-mta.html Easterling, K. (2014). Extrastatecraft: The power of infrastructure space. Verso. Fitzsimmons, E. G. (2016, December 14). With Second Ave. Subway, Cuomo Has Hands-On Role and Eye on the Future. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/nyregion/second-ave-subway-andrew-cuomo.html Fitzsimmons, E. G. (2018, May 7). How Can the M.T.A. Rescue the Subway When It Struggles to Deliver Basics? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/07/nyregion/mta-subway-nyc.html Flegenheimer, M. (2012, October 31). Flooded Tunnels May Keep City’s Subway Network Closed for Several Days. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/31/nyregion/subways-may-be-shut-for-several-days-after-hurricane-sandy.html Gelinas, N. (2017, June 22). Who Runs the MTA? City Journal. https://www.city-journal.org/html/who-runs-mta-15281.html Henke, C. R., & Sims, B. (2020). Repairing Infrastructures: The Maintenance of Materiality and Power. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11771.001.0001 Henke, C., & Sims, B. (2020). Repairing infrastructures: The maintenance of materiality and power. The MIT Press. Larkin, B. (2013). The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 327–343. Mahler, J. (2018, January 3). The Case for the Subway. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/03/magazine/subway-new-york-city-public-transportation-wealth-inequality.html McKinley, J. (2017, July 12). New Yorkers Look for ‘Summer of Hell’ Source and Find Cuomo. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/12/nyregion/new-yorkers-look-for-summer-of-hell-source-and-find-cuomo.html MTA. (2018). MTA 2015-2019 Capital Program. MTA. (2019). MTA 2020-2024 Capital Program. MTA. (2020). SAP Final After Action Report. Office of the New York State Comptroller. (n.d.). Financial Outlook for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority—Report 10-2022. Regional Plan Association (New York, N. Y. ). (2019). The Fourth Regional Plan for the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut Metropolitan Area: Making the region work for all of us. Regional Plan Association. Rosenthal, B. M. (2017, December 29). The Most Expensive Mile of Subway Track on Earth. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/28/nyregion/new-york-subway-construction-costs.html Rosenthal, B. M., Fitzsimmons, E. G., & LaForgia, M. (2017, November 18). How Politics and Bad Decisions Starved New York’s Subways. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/18/nyregion/new-york-subway-system-failure-delays.html Roy, A. (2009). WHY INDIA CANNOT PLAN ITS CITIES: INFORMALITY, INSURGENCE AND THE IDIOM OF URBANIZATION. Planning Theory, 8(1), 76–87. Rubinstein, D. (n.d.). New book argues Cuomo’s 2nd Avenue Subway push exacerbated MTA’s 2017 decline. POLITICO. Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.politico.com/states/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2020/01/15/new-book-argues-cuomos-2nd-avenue-subway-push-exacerbated-mtas-2017-decline-1251383 Simone, A. M. (Abdou M. (2004). People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16(3), 407–429. Somers, J. (2015, November 13). Why New York Subway Lines Are Missing Countdown Clocks. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/11/why-dont-we-know-where-all-the-trains-are/415152/ Sullivan, R. (2013, October 23). Could New York City Subways Survive Another Hurricane? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/27/magazine/could-new-york-city-subways-survive-another-hurricane.html