What defies borders?

This research was conducted on the traditional and unceded territory of the Lenape peoples, on the island of Mannahatta in Lenapehoking.

On the Porosity of the US–Mexico Border in El Paso, Texas

El Paso–Juárez, also known as Juárez–El Paso, is an urbanized area that straddles the border between Mexico and the United States. With over 2.7 million people residing in the area, the El Paso–Juárez region is home to the largest bilingual and binational work force in the Western Hemisphere. (Chamberlain, 2007)

Jain, Samat K. Juárez and East & Central El Paso from Ranger Peak. 2010. Photograph. 2048x1266 pixels. Flickr

The stretch of borderlands at El Paso–Juárez as a locale serves as a rich repository for studying the effects of a political border. It serves as a confluence of conditions that jeopardize access to infrastructure, natural resources and culture, infringes on the rights of indigenous peoples, and interrupts the natural patterns of non-human actors and their habitats.

In El Paso, the border is both visible and invisible, and operates between two extremes of physical and ideological porosity. Through an exercise of locating and spatializing these relationships, we work to understand how a border can impact those on either side beyond the material and physical division of space. The layered and multi-scalar approach of the project seeks to frame map data, images, and writing as an overlapped, specific, and ongoing cartography of controversy.

Aerial imagery from Google Earth.

This project takes a closer look at the porosity of the border for four entities: energy, humans, capital, and non-human actors.

The border as a delineation of responsibility

The border acts as a delineation of responsibility in a manufactured situation of natural gas dependency.

The electrical power grid that powers North America is divided into multiple synchronous grids. The two major grids are the Eastern Interconnection, which reaches from central Canada to the Atlantic, south to Florida, and back west to the foot of the Rockies; and the Western Interconnection, which stretches from Western Canada to Baja California in Mexico, encompassing 14 Western states.

Data from U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The state of Texas primarily runs on its own electrical grid, called ERCOT, which was formed in order to avoid federal regulation. In 1999, then-Governor George W. Bush deregulated the state’s electricity delivery system, and allowed electricity prices to be left up to a market that skewed to the interests of private generators, transmission companies, and energy retailers. Natural gas in Texas is cheap. This cheapness combined with deregulation gave little financial incentive for the state to invest in weather protection and maintenance.

Images from NOAA VIIRS DNB Nighttime Imagery.

This past February, Texas was hit by three severe winter storms that caused a colossal electricity generation failure statewide, stranding 4.5 million homes and businesses without power for days. Caused by an inadequate winterization of the state’s natural gas infrastructure, news outlets failed to report that the winter storms in Texas also stranded customers across the border in Mexico: in two days, factories in industrial border towns that were getting their power supply from the United States reported 2.7 billion dollars in losses from blackouts.

This is only a fraction of Mexico’s dependence on U.S. natural gas.

Data from U.S. Energy Information Administration and Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting and OpenStreetMap contributors.

Mexico has 24 gas pipeline import points along the US–Mexico border at the time of writing, 12 of which are connected to Texas. While Mexico has focused on scaling its crude oil extraction infrastructure (U.S. EIA report, 2021), it has heavily relied on U.S. gas imports: in 2020, Mexico was importing more than 70% of its gas needs from abroad, with 90% of those imports coming from the United States. (Reuters, 2020) In Texas, where the border is not always present in the form of a physical barrier, these pipelines are occurring at a greater frequency due to weak physical border infrastructure and access to cheap natural gas.

When Texas was hit by storms in February, Governor Abbott directed the Railroad Commission of Texas to restrict out of state exports of natural gas produced in Texas, causing a diplomatic snafu that prompted some to question whether or not a Governor was allowed to authorize such large-scale decisions; especially one that potentially violated the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause. (Lopez, New York Times, 2021.) As we begin to hear more about Mexico’s plans to expand pipeline connections across the border in the United States, there are certainly important questions to be asked about the dependency that the United States has manufactured on its natural gas supply.

What are the risks that Mexico runs by continuing to rely on U.S. gas when the infrastructure clearly cannot support both the United States and Mexico in the face of the climate emergency? Is energy sovereignty possible for Mexico? As long as the pipelines continue to create even more porosity across the border and the U.S. continues to prioritize its natural gas rights, the border is merely a means to restrict access to a resource that Mexico has equal rights to.

Click to go back to border overview.

The border as a method of future fragmentation

The border acts as a method of fragmentation of groups that have resided over the borderlands for centuries.

Up until the end of the Mexican-American war in 1848, the states that now comprise the southern border of the United States were part of Mexico. However, for the centuries preceding this colonial conflict, the land was stewarded over by a multitude of Indigenous Native communities. The historic Tigua territory is located on the southeastern edge of what is now El Paso, and stretches across the Rio Grande/Bravo to the Mexican side of the border into Ciudad Juárez. (Ysleta del Sur Pueblo: Walking in the Footsteps of our Ancestors, dir. Rojas, 2017)

Data: Google. (n.d.). [Map of Historic Tigua Territory]. Retrieved April 17, 2021. Overlay data from Native Land Digital

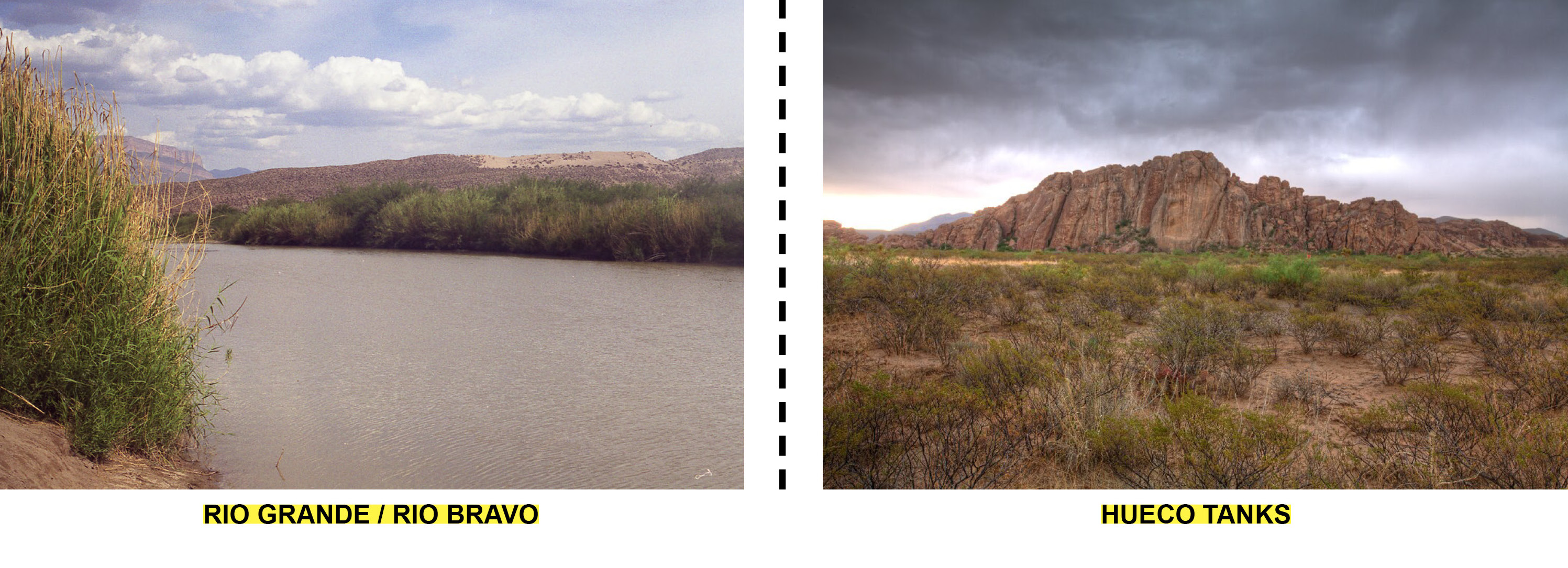

Ysleta del Sur Pueblo Tigua Nation is one of three federally recognized Native American tribes in the State of Texas. The current population is over 4,000 members nationwide, with about a third of those living within the El Paso area. There are two reservations on the United States side: one of which is incorporated into the metro, and the other on the very southeastern edge of the city. They also hold off-reservation land adjacent to the Hueco Tanks, a state park that is a sacred site for the Tiguas. (Rojas, 2017) The Rio Grande/Bravo lies on the Mexican side of the wall, which does not recognize the sovereignty of indigenous land. (Náñez, 2017) The Puente Zaragoza is the nearest United States Customs and Border Patrol crossing that connects the two divided lands and communities, located in between the two reservations on the United States side. The separation of these populations, their historic territory, and sacred sites is an injustice.

(Left) Sussexbirder. Rio Grande, Texas. 2001. Photograph. 1024x653 pixels. Flickr (Right) Fuson, Kirk. Hueco Tanks in Rain Storm. 2009. Photograph. 1024x674 pixels. Flickr

This inequity is perpetuated by unequal border crossing laws. Rules and border crossing privileges vary according to citizenship and tribal lineage. Among other requirements, denizens looking to cross the border into the United States from the Mexico side must prove economic solvency with a minimum bank account balance. The cost of both the passport and visa is prohibitive for many Indigenous persons existing in subsistence economies. (Alianza Indígena Sin Fronteras and Leza, 2019)

Hise, Steev. March Against Border Wall at Border Social Forum in Juarez. 2006. Photograph. 1024x768 pixels. Flickr

There is a long list of Indigenous rights violations brought by the construction of the wall, and the Tigua people have taken a vocal stance against its erection. Federal studies at the beginning of the 21st century confirmed the important historical relationship between the Tigua and the land and river on both sides of the border in the El Paso - Ciudad Juárez area. As a result of this study, the U.S. government signed an agreement with the tribe in January 2007 stipulating its responsibility to help the Tigua develop the tribe’s potential land and water rights claims “and to take actions consistent with those rights.” Yet, construction of the border fence was brought to its current condition: severing Tigua traditional lands and impeding access to sacred sites that have been used by the community for over 300 years. (Guzman and Hurwitz, 2008)

Click to go back to border overview.

The border as capital gain

The border acts as a conduit for capital gain through politically-motivated private contract financial awards.

The United States government has been afforded popular permission to take extraordinary measures at the U.S. - Mexico border under the pretenses of “national security”. The border wall, militarized patrols, security technology akin to a maximum security prison, among other initiatives are sold to the public as necessary infrastructures and protocols to ensure the safety of U.S. citizens and businesses. Annually, the United States Senate approves over $4.9 Billion dollars awarded to private-sector contractors to carry out many of these operations. Meanwhile, no measurable improvements to illegal immigration, drug trafficking, or undocumented imports/exports have been recorded. In fact, on the contrary, these statistics have steadily risen despite the U.S. government’s actions in defense of the border. It is clear, the true value of the border is in its role as a revenue generator.

Greenhill, Jim. 2006. Operation Jump Start. Photograph. 1,024x681 pixels. U.S. Army, U.S.–Mexico border near Nogales, AZ. Wikimedia Commons.

In 2006, President George W. Bush enacted Operation Jump Start, a plan to allocate $1.9 Billion dollars to the militarization of the U.S. - Mexico border. It entailed the mobilization of 156,000 troops annually to bases along the border, most notably Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. Operation Jump Start also called for hiring 6,000 new border patrol agents. Considering the cost per outfitting and equipping the average soldier is$15,000 (fulfilled by private-sector subcontractors), the largely non-violent threat of illegal border crossings, and the astronomical territorial profit-potential, this military mobilization in tandem with the Bush-Cheney administration’s war waged in the Middle East is a clear display of political maneuvering toward the fiscal profits of war.

Craighead, Shealah. President Trump in California. 2019. Photograph. 1024x683 pixels. Trump White House Archive on Flickr.

The militarization and government-awarded private contracts for border security and maintenance has only increased since Operation Jump Start. Fisher Industries was awarded $2 Billion to construct President Trump’s border wall in 2016. According to reports, the same 15 miles have been demolished and reconstructed continuously over the past five years. SAIC Corp. was awarded$973 Million in federal funding for border surveillance over the same time period. Perhaps most notably, a company called Kellog, Brown, and Root was awarded $24.4 million dollars annually for border maintenance and upkeep. This company is in fact a subsidiary of Halliburton, the oil conglomerate responsible for the U.S. invasion of Iraq. It is not a coincidence that most of the companies awarded these contracts are also key donors to many political campaigns. It is clear that the distinction between public and private interests has been eroded and that more often than not, private sector profits are directly related to legislation and political maneuvering.

Garland, Hadley Paul. The Fence. 2009. Photograph. 1024x751 pixels. Flickr

Click to go back to border overview.

The border as an arbitrary line in the sand

The border acts as an arbitrary line in the sand, devoid of context and completely at odds with ecological, animalian, and social reality.

The border is an artificial construct, and is oftentimes completely invisible other than as a form of human interference into the natural landscape. This interference is the line in the sand; at times literally manifesting as a wall which has immense impact on not only humans but natural entities. The irony of the line in the sand is its fakeness and at times its complete inability to deal with the natural landscape the United States attempts to etch it on, exposing the contradictory and uncanny nature of the border.

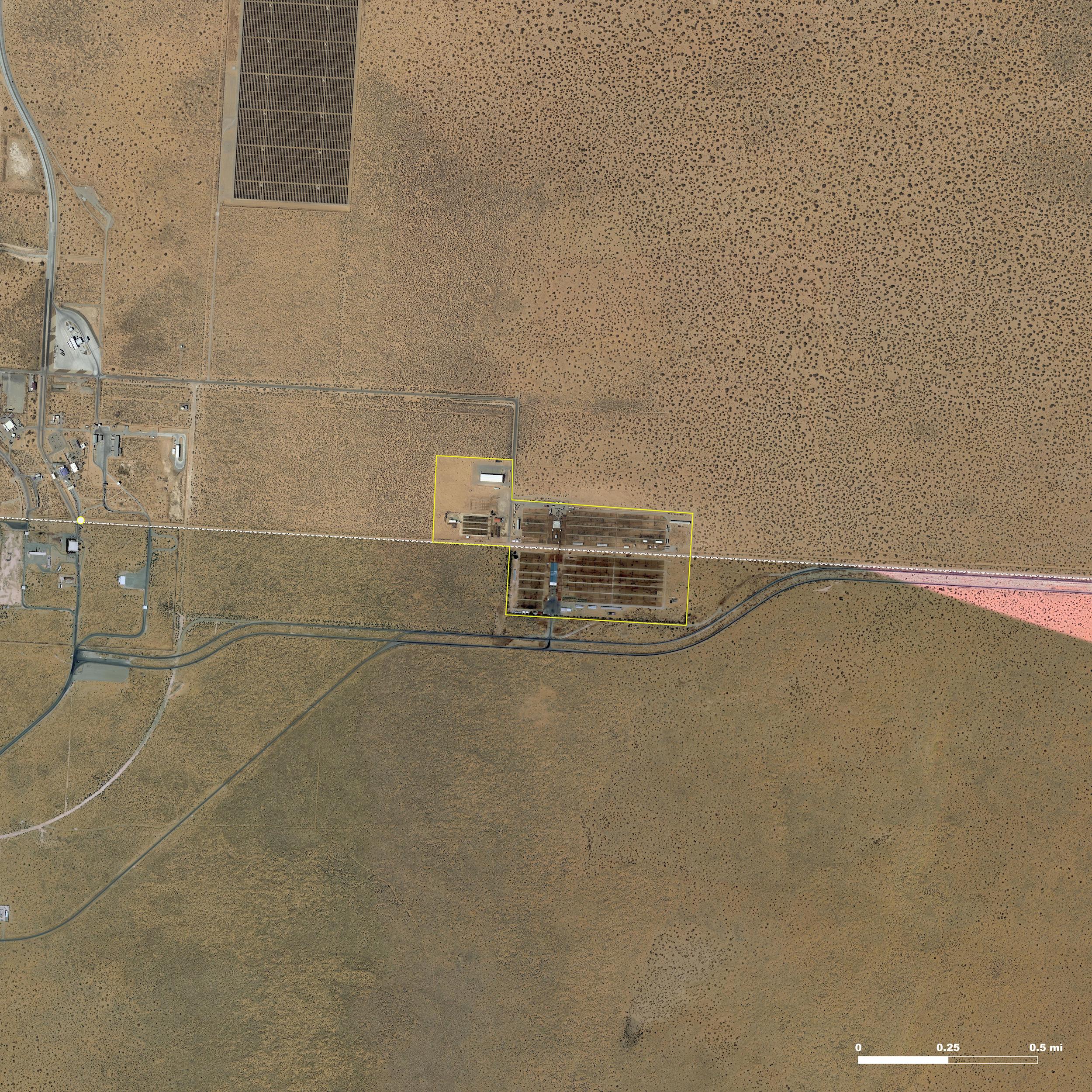

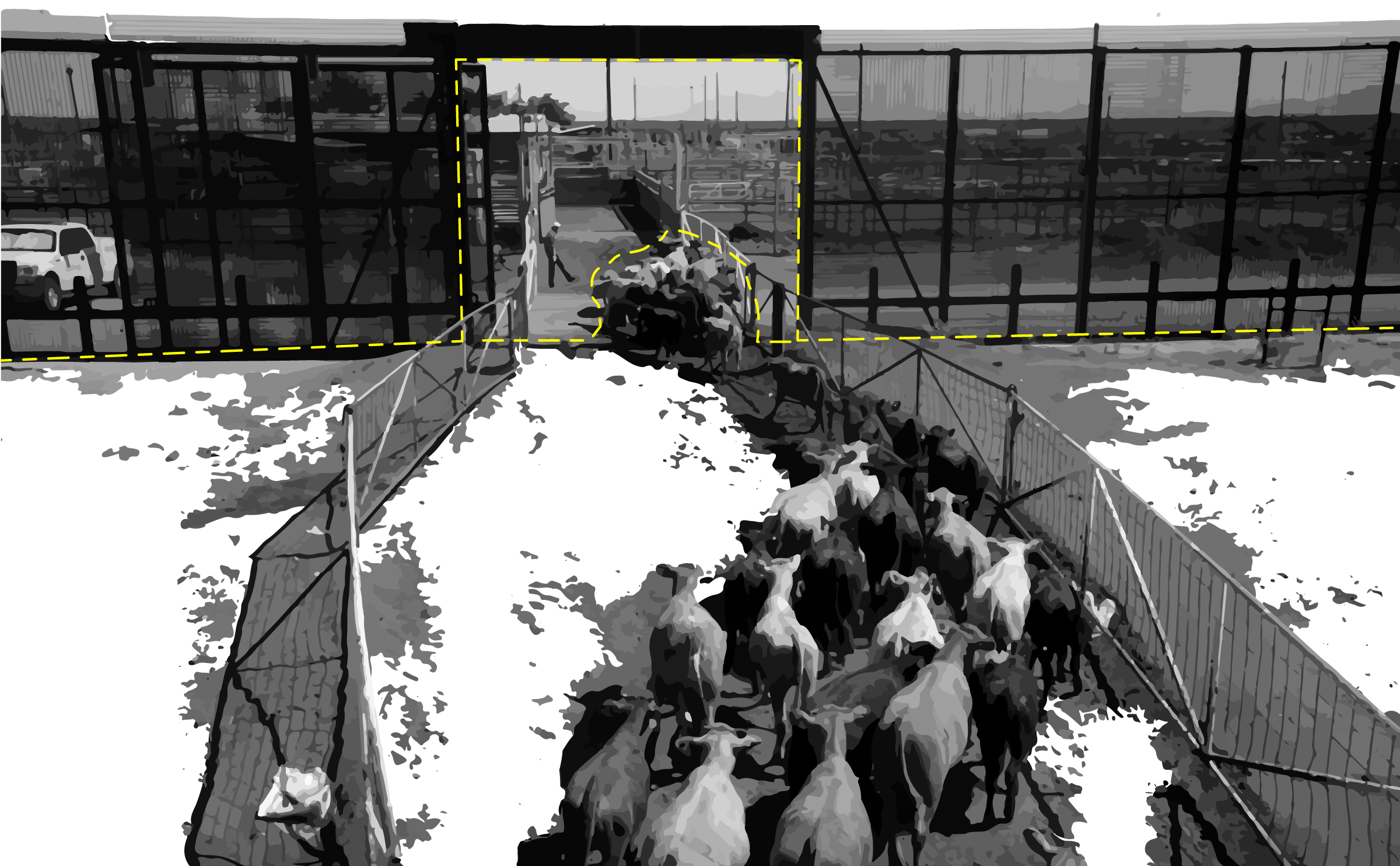

Founded in 1991, the facilities of the Santa Teresa and Ganadera Regional De Chihuahua Cattle Unions are the most modern and the largest on the U.S. - Mexico border. Up to 5,000 head of cattle flow from Mexico into the United States every day and the port of entry averages 300,000 head of cattle a year.

Cattle flow from Mexico to the United States through a gap in the wall. Humans are not allowed to cross.

Most cattle crossing the border from Mexico are feeder stock destined for pasture and feedlots in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and the Midwestern states. These facilities offer both practical and economic advantages over traditional border crossings. Livestock are penned and processed at the border, then walked into the United States, saving time and transportation costs by eliminating the need to truck between processing facilities on each side of the border, a procedure that increases costs and adds stress to the animals. (New Mexico Border Authority, 2021)

Arma, M. 2020. Screen Capture of Video Broadcast. KOAT 7 Action News Broadcast. 640x361 pixels.KOAT 7 Action News Broadcast.

The uncanniness of the facility is highlighted by its context and operation. Situated just west of El Paso, the union sits in the portion of the border built up as a vehicular barrier with a maintained track along the U.S. side to allow for fast and smooth vehicular operation of the United States Customs and Border Patrol. The union is one of the only punctures in the wall of this type along the entire border. A large sliding gate built into the intensive barrier, operated by cow hands on either side of the border, allows for the uninterrupted flow of beef cattle into the United States. Whilst the cattle cross the border freely, workers at the cattle union must stay on their respective side, executing the transition without ever moving through the gate they guide the cattle through. Beyond the workers is the question of wildlife, who without a commoditized value are disrupted from their natural habitat and entrapped by the artificial insertion of constructed border sections. (Armas, 2017)

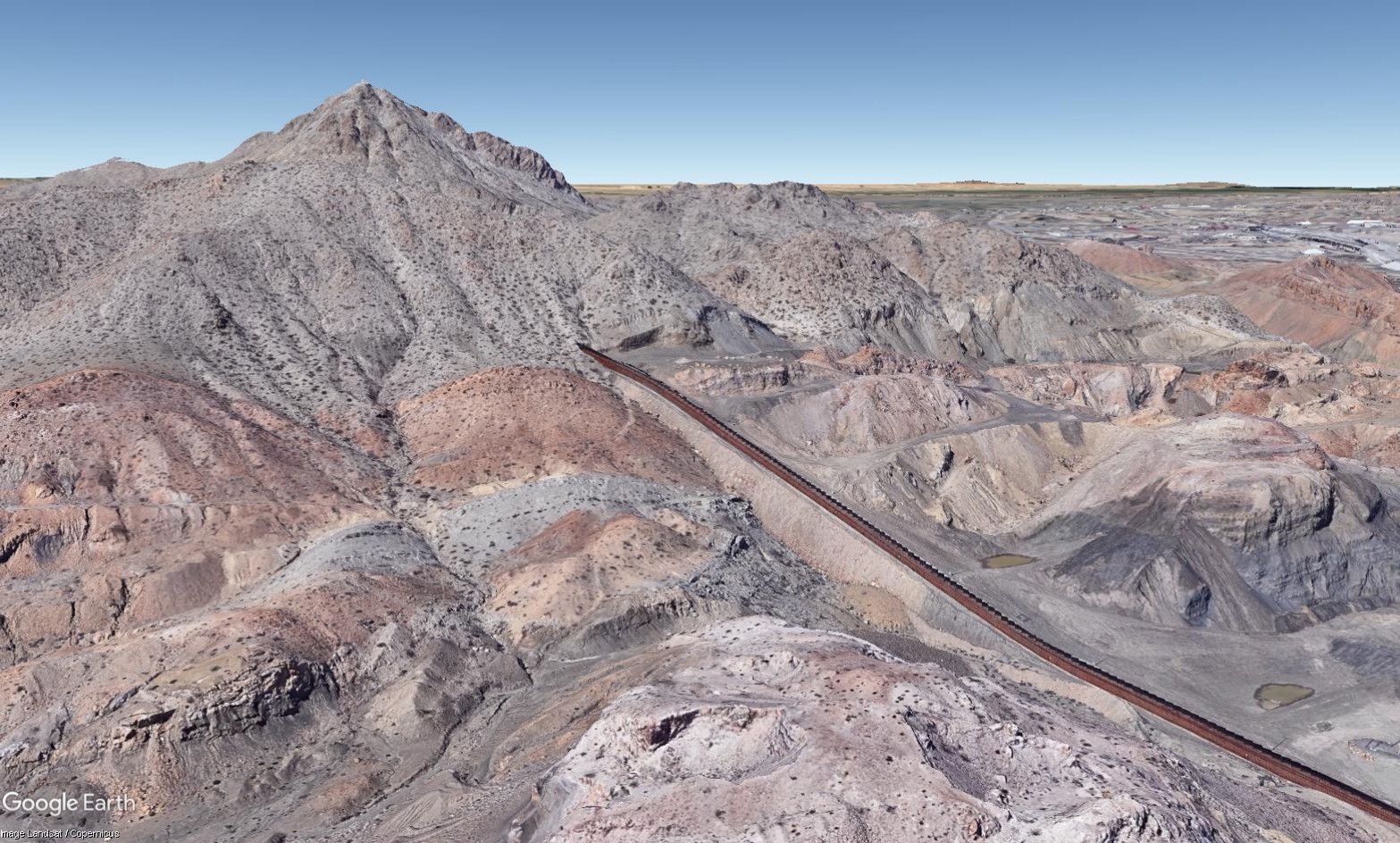

Where the cattle unions represent a line in the sand border as absurd in its deployment, the border at Mt Cristo Rey in El Paso and Ciudad Juarez proper represents the borders inability to reconcile with natural elements and the socially and environmentally damaging realities that arbitrary blockages in the ecosystem present. Cristo Rey, an important monument to Spanish Catholicism, along with its access point are located on the U.S. side of the landmass, and the border prevents easy passage for religious pilgrims crossing from Mexico annually. Further, the vehicular border wall which divides the U.S. and Mexico is incapable of scaling the mountain’s terrain, stopping on either side as a gash into the formation, rendering the wall futile in its constructed form.

Copernicus. 2021. 3D LandSat. Maxar Technologies. 1567x944 pixels. Google Earth.

Click to go back to border overview.

Conclusion

In light of the recent administration change in the United States, as well as the continually increasing probability of extreme weather events that instigated this project, the question of the efficacy of the border deserves to be asked again. The series of case studies presented above gives visibility to otherwise neglected layers of vulnerability, and repositions the history of the border cities as valves for the flow of commerce in the reality of late capitalism in opposition to the unfettered pre-capital reality that was enjoyed by the indigenous landscape.

As the controversy of the Trump Administration and its failed wall fade from the forefront of public interest, it is imperative that the energy, trade, and immigration policies of the United States, specifically with its southern neighbor, Mexico, do not also fade from visibility and conversation.

.png)

Works Cited

Literature and Articles

Alianza Indígena Sin Fronteras / Indigenous Alliance Without Borders and Christina Leza, Handbook on Indigenous Peoples’ Border Crossing Rights Between the United States and Mexico (Tucson, AZ), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/EMRIP/Call/IndigenousAllianceWithoutBorders.pdf

Armas, Marissa. “Border Wall Helps Business for Cattlemen but Poses Major Threat to Environment.” KOAT. KOAT, February 3, 2020. https://www.koat.com/article/border-wall-helps-business-for-cattlemen-but-poses-major-threat-to-environment/27473359

Chamberlain, Lisa. “2 Cities and 4 Bridges Where Commerce Flows,” New York Times, published 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/28/realestate/commercial/28juarez.html?pagewanted=2&_r=2&sq=Where

Michelle Guzman and Zachary Hurwitz, “Violations on the Part of the United States Government of Indigenous Rights Held by Members of the Lipan Apache, Kickapoo, and Ysleta del Sur Tigua Tribes of the Texas-Mexico Border” (Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 2008), 13. https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/borderwall/analysis/briefing-violations-of-indigenous-rights.pdf

Lopez, Oscar. “Mexico Cries Foul at Natural Gas Cutoff Ordered by Texas Governor,” New York Times, published February 18, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/18/world/americas/mexico-abbott-power-outages.html

Náñez, Dianna M., “A Border Tribe, and the Wall that will Divide It,” USA Today, USA Today Network, published 2017.

“Livestock.” New Mexico Border Authority. Accessed April 24, 2021. http://www.nmborder.com/Livestock.aspx

Reuters Staff, “Mexico to keep importing natural gas as U.S. exporters face oversupply,” Reuters, published January 3, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-gas/mexico-to-keep-importing-natural-gas-as-u-s-exporters-face-oversupply-idUSKBN1Z21RC.

U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Gulf of Mexico crude oil production will increase with new projects in 2021 and 2022,” Today in Energy, Energy Information Administration, published April 14, 2021. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=47536

Ysleta del Sur Pueblo: Walking in the Footsteps of our Ancestors, directed by Rudy Rojas (2017; El Paso, TX: Smoke Signals Design and Marketing, 2017) https://www.ysletadelsurpueblo.org/who-we-are

Data Sources:

U.S. Energy Information Administration

Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting and OpenStreetMap contributors, data available under the Open Database License.