Beyond the Origins and Destinations: Spatializing the issue of climate refugees

This project investigates publicly accessible spatial data on climate, conflict and migration, in relation to the absence of a legal definition of the term “climate refugee”. For this purpose, the work focuses on three case studies in the Sahel Region in Central Africa, where arguable climate-induced mass migration and conflict is taking place. The objective is to explore spatial complexities of establishing causal relationships between the three phenomena and develop a framework for further research, as well as contribute to the discussion on how climate migration can be addressed in terms of policy.

The Problem: The absence of a legal framework for climate refugees

The problem that triggered this research is that, in spite of the apparent evidence of the role that climate change plays in forcing massive migrations, there is neither a clear definition for this category of migrants, nor an international formal recognition that guarantees the rights of affected populations to protection and asylum and that ascribes the responsibility of the developed countries and the Global North (it is, the main emitters of greenhouse gases) towards the problem. However, as recognized by Jean-Claude Juncker (European Commission President) at State of the Union speech in 2015 “Climate change is one of the root causes of a new migration phenomenon. Climate refugees will become a new challenge – if we do not act swiftly”[1].

The gap in the current legal framework, the 1951 Refugee Convention, limits the term to only apply to “people who have a well-founded fear of being persecuted because of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, and are unable or unwilling to seek protection from their home countries”[2].This excludes the people displaced for reasons related to the environment degradation and climate change, who are mainly categorized as Internally Displaced Persons (IDP). Yet, “the distinction between refugees and internally displaced persons is a fundamental and integral characteristic of traditional refugee law defining the extent to which assistance will be made available to displaced persons”[3]. As Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary-General, former UN High Commissioner for Refugees, has argued that climate change is mainly causing internal displacements, nevertheless, “when they cross a border, they will not be considered refugees”[4]. This means that they cannot easily appeal for resettlement in another country. Instead, heir actions are criminalized as they seek to leave the worsening environmental conditions.

In light of the recent estimation made by The International Organization for Migration (IOM), there could be as many as 200 million such refugees by 2050. Although some efforts have been made to reach a possible legal definition, the question still remains: Why is there still no legal definition of the term climate refugee, when all the evidence indicates a dire need for such a framework?

The complexities: Establishing clear causal relationships

In our investigation, one of the main problems in defining “climate refugee” is not being able to establish the existence and shape of the causal relationship between climate change, migration and conflicts, since most of the time causal connections are intertwined or disguised behind one another in many different and complicated ways.

Despite the growing consensus in scholarly literature regarding the evidence for climate-induced migration, there is less consensus regarding the existence of climate-induced conflicts. For example, it is sometimes argued that “climate change may not of itself trigger a movement of people” or that “it does not necessarily cause people to take arms”, and that social, political and economic factors need to be taken into account to explain people’s decisions to migrate.

Nevertheless, it has been also argued that “given the likelihood that environmental change, migration, and conflict may happen in close proximity or succession, there is a need to more explicitly connect the three phenomena” [5], and also that “the spatial dimension is necessary for analyzing the connections between climate-related environmental change and violent battles” [6].

With this project, we intend to contribute mostly to the research on possible methodologies of data spatialization, in order to portray the relations between the 3 types of phenomena.

The Project: Three case studies in the Sahel, Africa

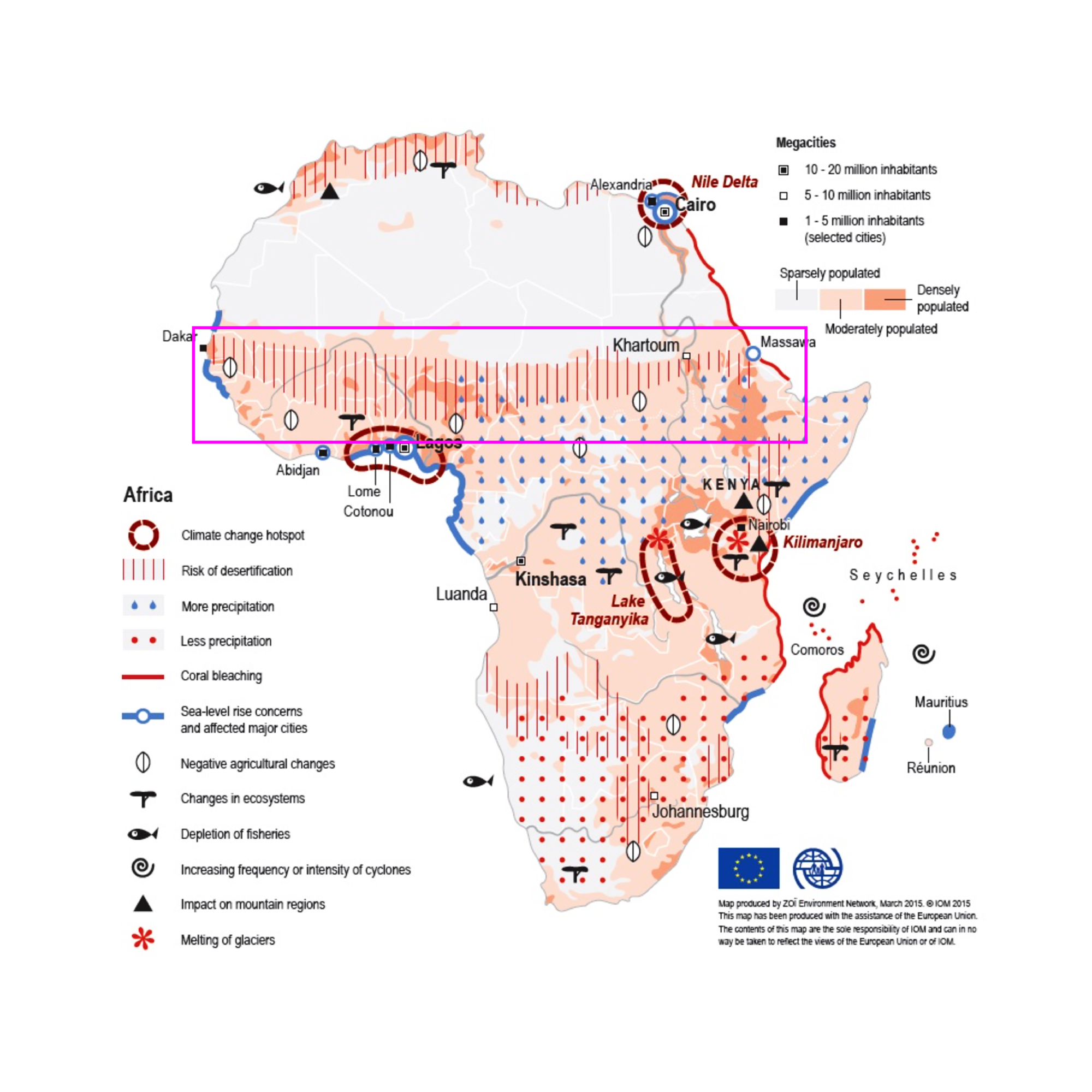

Source of Figure 1 is from IOM, 2015[7]

This research is focused in the Sahel area of Central Africa, since it is a region acutely affected by climate change (Figure 1)[7], which heavily threatens the environmental and livelihood conditions of the region. More precisely, we chose three regions within Nigeria, namely Northwestern Sokoto and Zamfara, Central Benue and the Northeastern Borno state (located by Lake Chad).

These three particular case studies were selected as they present distinct types of climate induced conflicts (Cattle rustling and rural banditry, Farmer-Herder conflicts, and Boko Haram) and patterns of migration (transnational migration, internal displacement). Additionally, considering the causal relationships within these three different locations may help us avoid site-specific biases and prevent us from drawing hasty conclusions without due consideration.

For each of the chosen cases we strive to answer the question: can we consider the displaced population as ‘climate refugees’?

SOKOTO-ZAMFARA, NORTH WEST NIGERIA

Timeframe: 2011, peak in 2018 - Present

Type of Scenario: Exacerbation of local conflicts by resource scarcity encouraged new types of violence, which in turn resulted in internal displacement and international migration.

Causal relationship(s):

- Climate Change → Conflict (tribal) ~ Conflict (banditry) → Migration

- Climate Change → Migration

- Conflict (banditry) ~ Islamic State → Migration

- → = effect

- ~ = instrumental variable/opportunity for

- Local conflicts + population increase + climate change (desertification) -> increase in hostility in existing conflicts -> new violence -> migration

Description: Sokoto and Zamfara states in the North West Nigeria experience an unprecedented crisis of multiple types of armed conflicts, which accumulated over the last 3 decades. Both the local herders (mainly Fulani people) and farmers (mainly Hausa people) have developed individual combat units: ‘bandits’ acting on behalf of the herders, marginalized from local political power, and state-reinforced ‘vigilantes’, acting on behalf of the Hausa farmers. The existing tensions set the scene for further gang activities detached from the local conflicts. These have surprisingly united both Fulani and Hausa descendants in cattle rustling, mass kidnappings and armed robberies. The strained local security forces are helpless against the incoming third wave of antagonists: Jihadists and Boko Haram, which in turn are highly centralized, well organized and equipped.

In the past, recurring disputes over land and natural resources have been successfully resolved by the local authorities. However, regular disputes have been recently exacerbated by the shortening of the rain period [8], steady desertification of farmland [9], and coinciding with rapidly increasing resource scarcity, rooted in peaking fertility rates among North West Nigerian women. The competition for land suitable for both farming and grazing became hostile. Fulani herders were further deprived of rights to use forest lands, given by the newly elected democratic government in 1999 to Hausa farmers, many of which were particularly favored by the Abuja officials. In 2000 Zamfara became the first Nigerian State to adopt Islamic Law, which was justified as a way to tackle the economic crisis. Since then, the capital has been repeatedly accused of dismissing violence and displacement in this region and relinquishing the responsibility for its residents.

While the second layer of the conflict could be traced to 2011, a notable increase in migration and deaths in Zamfara region in 2018 indicate a visible aggravation of conflict. According to current estimations, since 2010 and only in the Zamfara state, around 8,000 people have been killed, 200,000 internally displaced, and 60,000 seeked refuge in neighbouring countries, mostly Niger [10].

THE MIDDLE BELT: BENUE STATE

Timeframe: 2014 - peak in 2018 - Present

Type of Scenario: Scarcity + Environmental degradation as method of conflict

Causal relationship(s): Climate change (drought and desertification) -> migration (?) conflict -> displacement (IDP Camps + Host Communities)

Description: This case study explores the conflict of farmers and herders in Nigeria. It is caused by the advancing of drought and desertification in the north, forcing Fulani people and other pastoral communities to migrate towards the south in search for alternative pastures and sources of water for their cattle. When the herders arrive to the lands of the Middle Belt, they have to compete for these resources in a context of scarcity, which leads to conflict between the local farmers and the newly arrived herders. The farmers and herders’ conflict has become Nigeria’s gravest security challenge, now claiming far more lives than the Boko Haram insurgency. Benue has been pointed out to be the most impacted state, due to the new laws banning open grazing in Benue and Taraba states. In terms of its timeline, the conflict started worsening in 2014, reaching its peak in January 2018 after the attacks on several Guma and Logo farmer communities [11]. While the causal connection of climate change in the north of Nigeria leading to migration to the south is very clear, the causal connection of climate change leading to conflict has been pointed out to be in need of further spatial study. As such, we have explored supplemental methods to spatial research through chronologically mapping how the three phenomena are interconnected, contextualized by testimonies of people that have been displaced to IDP Camps or host communities due to the conflicts.

BORNO, LAKE CHAD BASIN

Timeframe: Lake Chad Shrinking: 1960s-Present; Boko Haram Insurgency: 2002-2015-2018/19-Present

Type of Scenario: Climate change effects and resource scarcity coupled with attacks and violence by insurgence groups resulted in internal displacement and cross-border migration

Causal relationship(s):

- Climate Change → Migration (independent from Boko Haram insurgency)

- Climate Change ~ Boko Haram → Conflict → Migration

- Climate Change + Conflict → (Constrained) Migration

- (Constrained) due to conflict

- → = effect

- ~ = instrumental variable/opportunity for (i.e. Boko Haram took advantage of this vulnerability)

- += combination and exacerbating factor

Description: The third case explores the Nigerian State of Borno, part of the Lake Chad Basin. The area is a convergence point of a complex humanitarian disaster – with the courtesy of violence and climate change in remote, ungoverned areas. For almost two decades, the northeast Nigeria have been subject to the insurgency of the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. This region is also known for its poor environmental conditions that mostly manifest in land desertification and water scarcity.

Experts say that climate change is a key factor fuelling the insurgency of the armed group Boko Haram since 2002, which is aimed at creating an Islamic State in North East Nigeria [12]. North East Nigeria used to be peaceful with more than 50 percent of the population making a living from farming, fishing and livestock production [13]. Many people in the region lost their livelihoods following increasing aridity and decrease of discharge in the Komadugu Yobe River caused by climate change, hence becoming vulnerable to being recruited by Boko Haram [14].

Environmental problems connected to scarcity of water resources and aridity of drylands may serve as causal factors of conflicts, but also as ‘environmental push elements’ causing migration – with 2.3 million people across the region displaced [15]. The decision to migrate is taken when the level of scarcity is no longer possible to sustain living, or, to flee the Boko Haram insurgency, when they are able to.

As the insurgency sieged the vulnerable areas with poor environmental conditions, and inflicted heavy conflicts, the tyranny forced residents of Borno to migrate as a way to escape. When conflicts peaked in January 2015 (Boko Haram kidnapping women and children) [16], we saw stories of migration as somehow a testimony of survival from fleeing the insurgency. Ultimately, the IDPs and migrants move to areas where there is more access to livelihood or to refugee camps and host communities.

The Conclusion: More spatial research and personal testimonies

In this research we shed light on the complexities that hinder any attempts of establishing a legal definition of a “climate refugee”. Personal testimonies indicate a chain of events leading to the migration, starting with climate change induced resource scarcity and ending with international and internal flight from violence. As indicated by numerous research studies, a causal relation between climate vulnerability and appearance of conflict could not be easily established. However, this study has put forward stories of 3 states in Nigeria, which appear to be in different stadiums of the same process.

Despite lacking sufficient geographical data, we recommend further spatial processing and mapping as a way to portray problems of climate migration. Due to the physical nature of the 3 coinciding phenomena (migration-vector, conflict-point, climate change-region), GIS analysis could in fact provide the only viable methodology of study. Furthermore, future research could rely on the personal testimonies of displaced persons more than just as a narrative-building supplement. We recognize them as a valuable contextualizing tool with a humanistic perspective that could complement oversimplified causal relations generated by data visualization. They could become the missing link, bringing forward more obscure and complex chains of events that lead to inevitable mass migrations throughout the globe.

In response to the prevailing assumption that the internationally acclaimed term ‘refugee’ should not be extended to cover those fleeing climate induced changes, we recommend taking into account the influence of climate vulnerability on competition over scarce resources, which has already taken an especially life-threatening turn in Nigeria since 2010.

Remarks on using the available data:

- IOM’s evaluations of existing IDP camps and host communities are a comprehensive source of information. However, the statistics of ‘reasons for migration’ could be extended from one to multiple most common responses.

- Datasets regarding directions of migration from Nigeria’s territory have not been made available to us from IOM. Vectors of movement from Sokoto and Zamfara states, as documented in the video, have been redrawn from a website article, published by IOM in 2018.

- In personal testimonies, some names have been changed by the interview publishers to protect the identity of the displaced individuals. At the same time, several origins of migration have been difficult to establish as well, while some village names do not exist in any repository of geographical names, or have been changed on purpose as well.

REFERENCES

Cited Literature:

[1] Apap, J. (2019). The Concept of ‘Climate Refugee’: Towards a Possible Definition, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), 8. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2018)621893.

[2] Apap, J. (2019).

[3] Apap, J. (2019).

[4] Guterres, A. (2011). Statement by Mr. António Guterres, Former United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Intergovernmental Meeting at Ministerial Level to mark the 60th anniversary of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, Geneva, December 7, 2011, Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/admin/hcspeeches/4ecd0cde9/statement-mr-antonio-guterres-united-nations-high-commissioner-refugees.html.

[5] Freeman, L. (2017). Environmental Change, Migration, and Conflict in Africa, The Journal of Environment & Development, 26(4), 361. https://doi.org/10.2307/26392658.

[6] Madu, I.A., & Nwankwo, C.F. (2020). Spatial pattern of climate change and farmer–herder conflict vulnerabilities in Nigeria. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10223-2. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10708-020-10223-2#citeas

[7] International Organization for Migration. (2015). Europe and Africa. Retrieved from

https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/europe-and-africa

[8] International Crisis Group 2020. Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/288-violence-in-nigerias-north-west.pdf (As reported in 2008, the length of the rainy season observed in Nigeria shrank from 150 to 120 days, original source is from “Nigeria: Rainy season is getting shorter – Nimet”, Daily Trust, 10 March 2008.)

[9] Medugu, Nasiru & Majid, M. & Johar, Foziah. (2009). The Consequences of Drought and Desertification in Nigeria.

[10] International Crisis Group 2020. Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/288-violence-nigerias-north-west-rolling-back-mayhem

[11] International Crisis Group. (2018). Stopping Nigeria’s Spiralling Farmer-Herder Violence. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/262-stopping-nigerias-spiralling-farmer-herder-violence

[12] Council on Foreign Relations. (2021). Boko Haram in Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/boko-haram-nigeria

[13] Sparkman, T. (2019). New Report Addresses Climate and Fragility Risks in the Lake Chad Region. Retrieved from https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2019/05/report-addresses-climate-fragility-risks-lake-chad-region/.

[14] IUCN. (n.d.) Komadugu Yobe Basin, upstream of Lake Chad, Nigeria. Retrieved from https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2011-097.pdf

[15] Kogoui Kamta, Frederic Noel & Schilling, Janpeter & Scheffran, Jürgen. (2020). Insecurity, Resource Scarcity, and Migration to Camps of Internally Displaced Persons in Northeast Nigeria. Sustainability, 12, 6830. Retrieved from doi:10.3390/su12176830.

[16] Council on Foreign Relations. (2021).

Supporting Literature:

ACTED. (n.d.) In the Lake Chad basin, populations are trapped between climate change and insecurity. Retrieved from https://www.acted.org/en/in-the-lake-chad-basin-populations-are-trapped-between-climate-change-and-insecurity/

Agence France-Presse. (2020). 42,000 Flee Violence in Northwest Nigeria. Retrieved from https://ewn.co.za/2020/05/12/42-000-flee-violence-in-northwestern-nigeria

UNHCR. (2021). Surging violence in Nigeria drives displacement to Niger. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/briefing/2021/3/603dfeaa4/surging-violence-nigeria-drives-displacement-niger.html

Egbejule, E. (2018). Deadly cattle raids in Zamfara: Nigeria’s ‘ignored’ crisis. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/8/20/deadly-cattle-raids-in-zamfara-nigerias-ignored-crisis

Griffin, T. (n.d.). Lake Chad: Changing Hydrography, Violent Extremism, and Climate-Conflict Intersection. Retrieved from https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/Expeditions-with-MCUP-digital-journal/Lake-Chad/

International Crisis Group 2020. Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/288-violence-nigerias-north-west-rolling-back-mayhem

Kindzeka, M.E. (2021). 5,000 Nigerians Displaced by Boko Haram Ready to Return, Cameroon Says. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/africa/5000-nigerians-displaced-boko-haram-ready-return-cameroon-says

Medecins Sans Frontiers. (2019). Nigeria: Tens of thousands displaced by violence in Zamfara state. Retrived from https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/what-we-do/news-stories/news/nigeria-tens-thousands-displaced-violence-zamfara-state

Tower, A. (2017). Shrinking Options: The Nexus Between Climate Change, Displacement and Security in the Lake Chad Basin. Retrieved from https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/shrinking-options-nexus-between-climate-change-displacement-and-security-lake-chad-basin

Zieba, F. W., Yengoh, G. T., & Tom, A. (2017). Seasonal Migration and Settlement around Lake Chad: Strategies for Control of Resources in an Increasingly Drying Lake. Resources, 6(3), 41. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/resources6030041

Datasets:

ACLED. (2021). Conflicts in Nigeria from January 1997 to March 2021. Retrieved from https://acleddata.com/curated-data-files/

Google Earth. (2021). Historical imagery of Nigeria from 1984 to 2020. Retrieved from https://earth.google.com/web/@9.0338725,8.677457,447.34097653a,2938707.2331043d,35y,0h,0t,0r

International Organization for Migration. (2019). Migration Flows in West and Central Africa. Retrieved from https://migration.iom.int/data-stories/migration-flows-west-central-africa

International Organization for Migration. (2021). Nigeria Displacement - [IDPs] - Baseline Assessment [IOM DTM]. Retrieved from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/nigeria-baseline-data-iom-dtm

International Organization for Migration. (2021). Nigeria Displacement - [IDPs] - Location Assessment [IOM DTM]. Retrieved from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/nigeria-location-assessment-data#:~:text=DTM%20location%20assessment%20is%20to,for%20more%20detailed%20site%20assessments.

U.S. Geological Survey Earth Explorer. (2021). Nigeria Landsat-8 Aerial Imagery. Retrieved from https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/