Visualizing the History of Cooperativism in Barcelona's Poblenou Neighborhood

Introduction

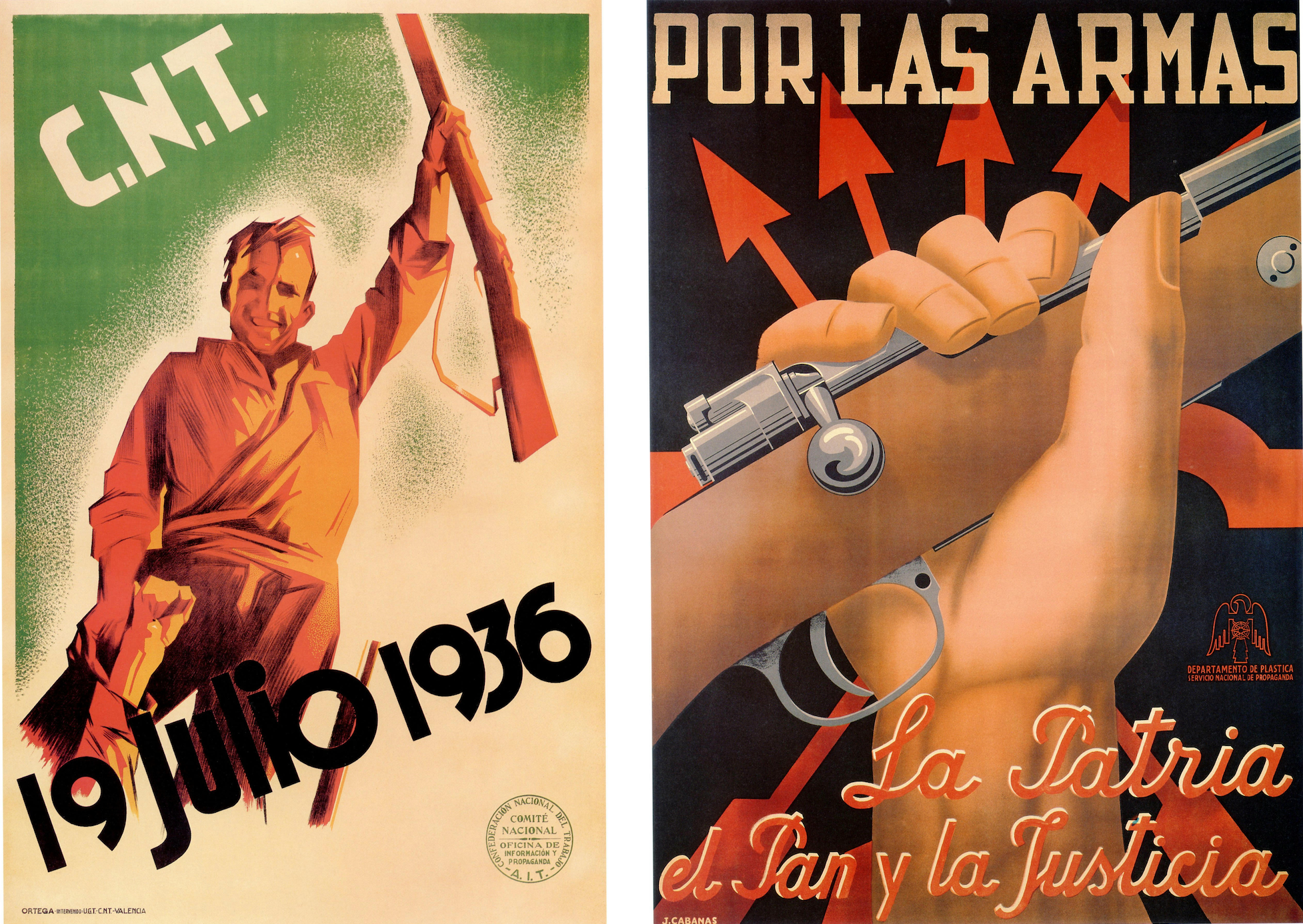

On July 19, 1936, Barcelona’s masses, organized by anarchist and socialist unions, successfully defended the city from a fascist-led coup. In the months that followed, workers transformed the city by taking control of the majority of the city’s industries, infrastructures, and businesses.

Posters from the Spanish Civil War.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Posters from the Spanish Civil War.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Drawing inspiration from Silvia Federici’s claim that to examine anti-capitalist commons is to see that “another world is growing, like the grass in the cracks of the urban pavement, challenging the hegemony of capital and the state and affirming our interdependence and capacity for cooperation,” and James Scott’s suggestion that “brief utopian moments illustrat[e] what a differently conceived city might be like,” I visualize the history of cooperativism in Barcelona’s Poblenou neighborhood in order to make sense of the unprecedented success of collectivization in the Spanish Civil War and to imagine the potentials of urban collectivization today.

Poblenou’s Industrial History

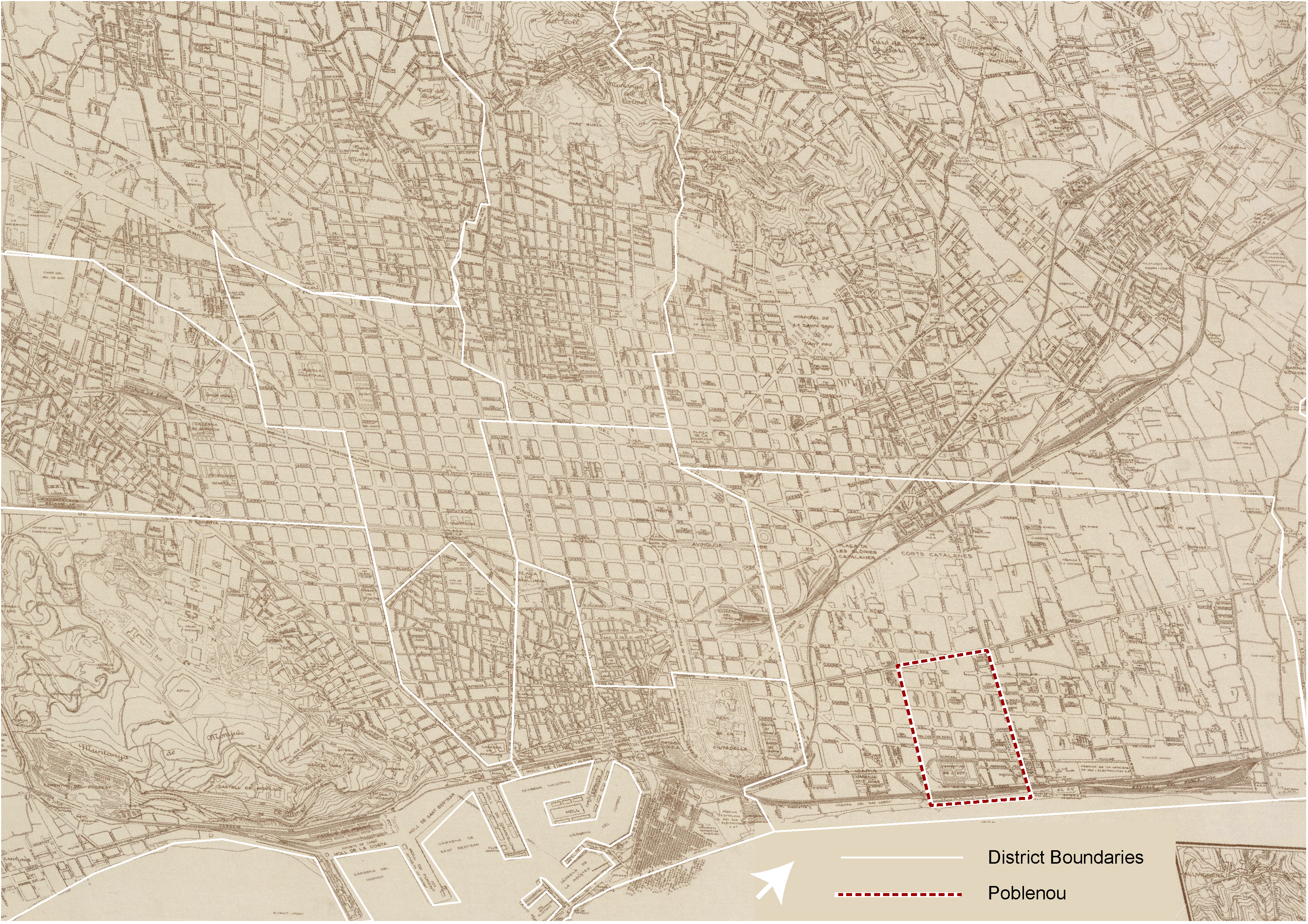

Locating Poblenou. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Locating Poblenou. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

In this project I focus specifically on Poblenou. The neighborhood was dubbed the “Manchester of Catalonia” for its high concentration of industry and was at the center of Barcelona’s rapid industrialization.

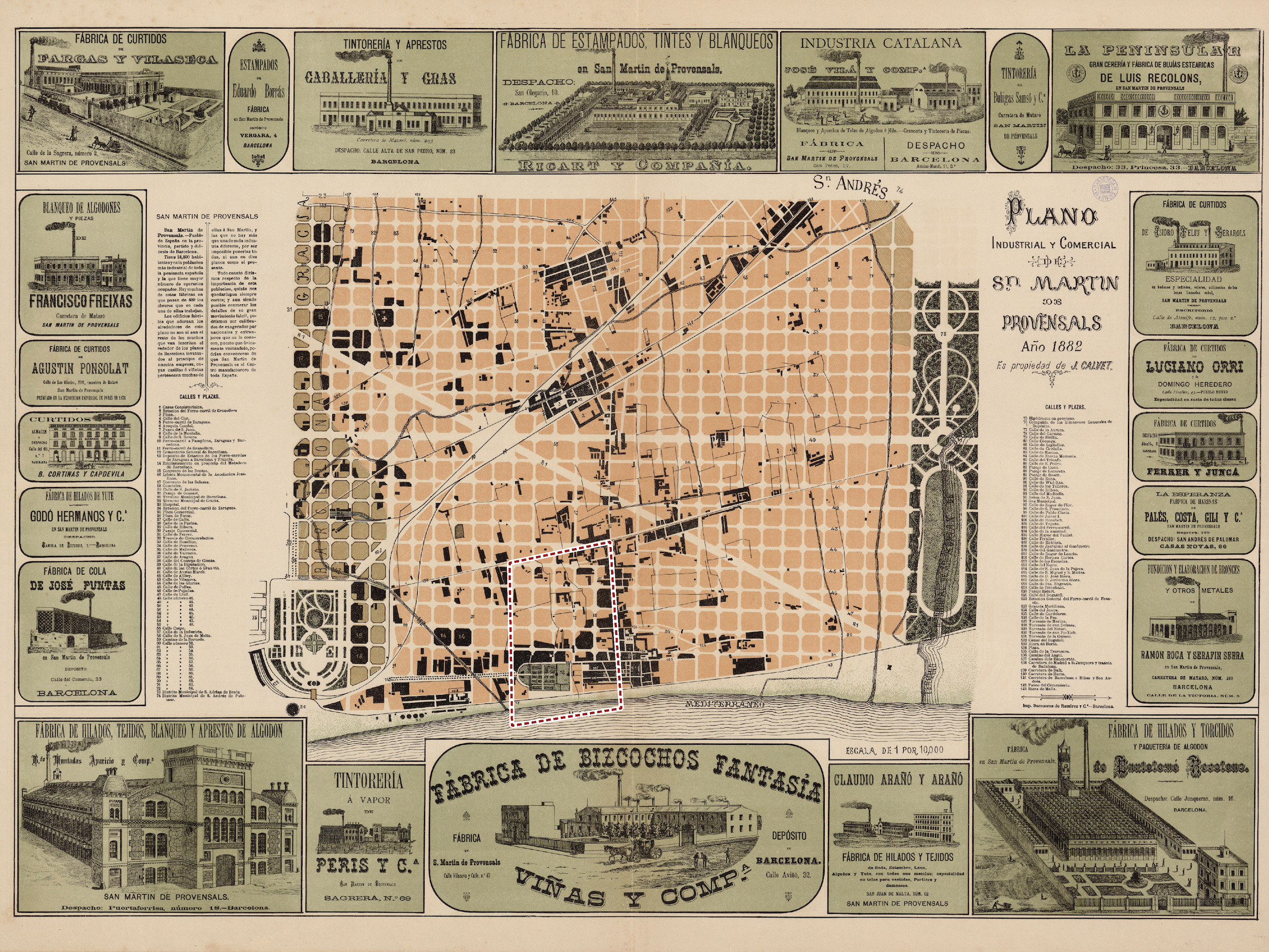

1882 map advertising Poblenou’s industries. Source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

1882 map advertising Poblenou’s industries. Source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Notably, this 1882 map imposes the existing buildings onto a gridded plan. The grid was designed by Ildefons Cerdá with the intention to organize the rapidly expanding city. While liberal in rhetoric, the plan did not serve to advance Cerdà’s liberal vision for the city. Instead, local landlords mobilized against the project, and the government did not have enough money to enforce the plan as an equalizing force. Here we see an example of the market’s inability to solve the problems of poverty and overcrowding it had created.

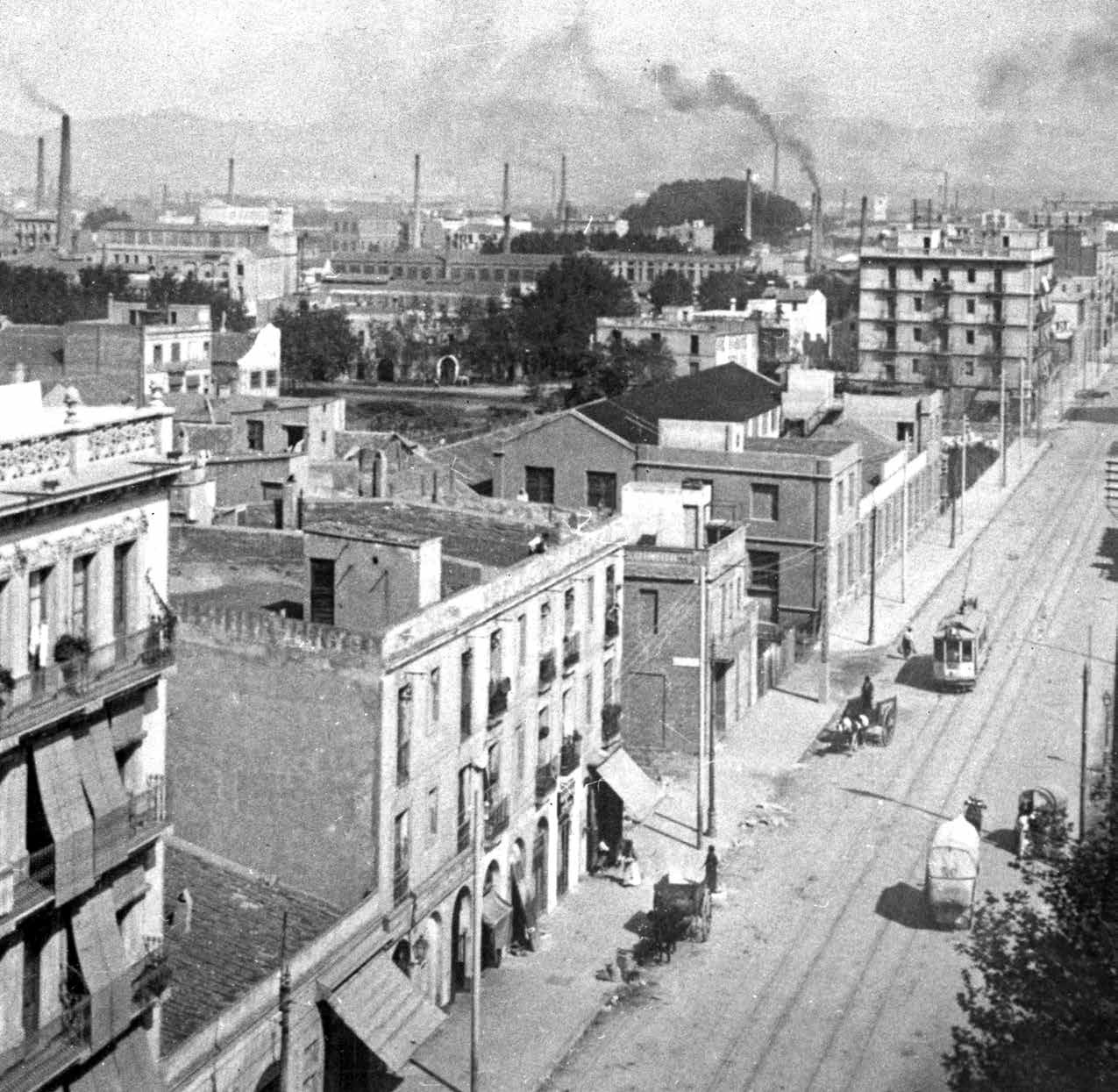

Poblenou’s industrial landscape. Source: Marc Dalmau

Poblenou’s industrial landscape. Source: Marc Dalmau

Despite the grid’s attempt to solve social ills, life in working-class neighborhoods, including in Poblenou, remained incredibly difficult. Neglected by the state and exploited by the factories, working-class people developed their own structures of collaboration and reciprocity. In contrast to the top-down imposition of Cerdà’s plan, these alternatives emerged from the existing urban fabric.

The Cooperative Movement

Source: Marc Dalmau

Source: Marc Dalmau

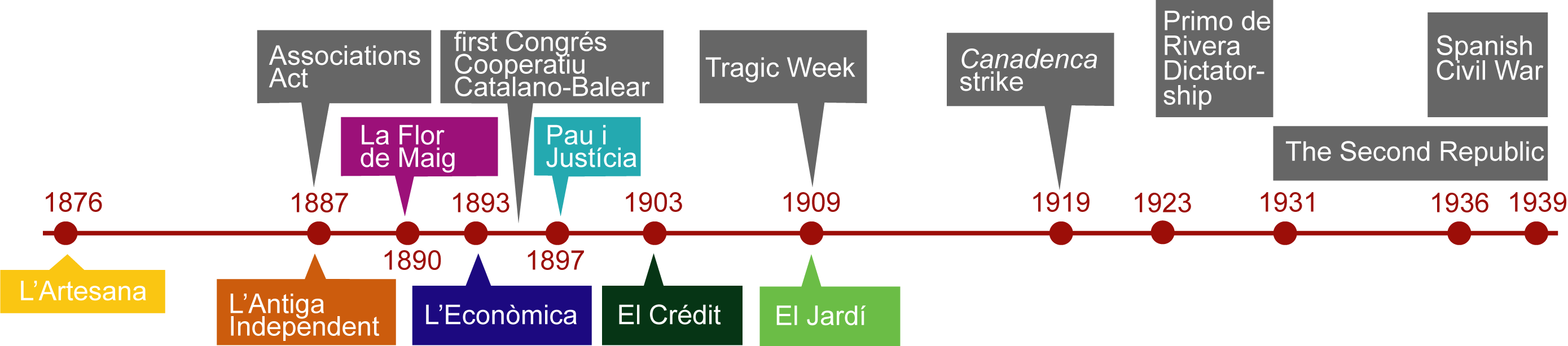

The following timeline indicates the year each Poblenou cooperative was founded in the context of significant historical events. The colors for each cooperative will be consistent through the rest of this page.

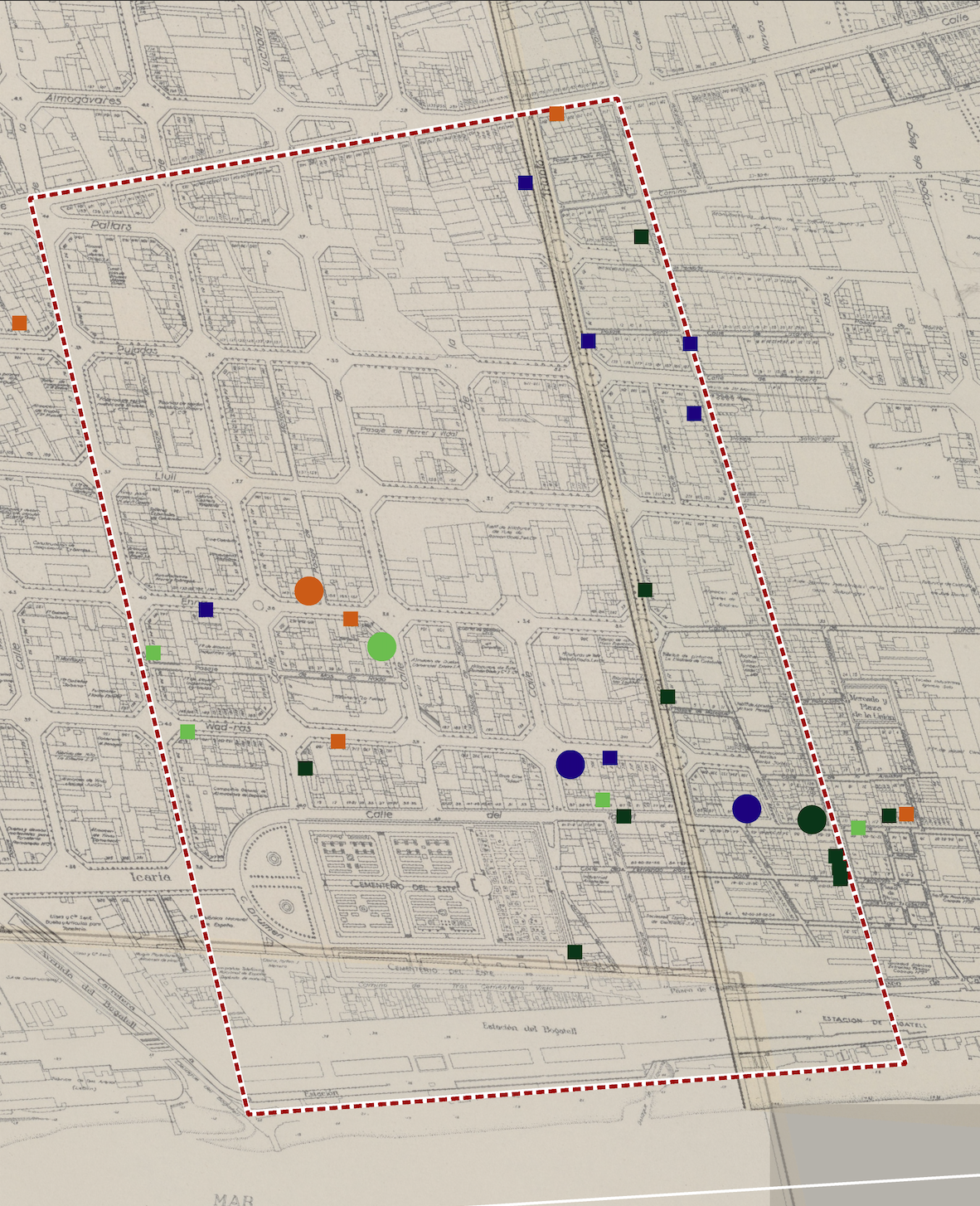

The formation of a cooperative began when a small group of people decided to pool their resources for a communal fund through which they could purchase basic necessities, such as bread or oil. They would then distribute these necessities below market price in order to set up an exchange outside of the capitalist extraction through profit inflation. As these cooperatives grew – in number of associates, goods sold, and ultimately by purchasing a building from which to operate – they also developed a cultural function. Cooperatives would host various cultural events, including festivals, womens’ and childrens’ groups meetings, and plays.

The following map follows the growth of La Flor de Maig and is illustrative generally of the path many cooperatives followed.

This examination of La Flor de Maig highlights how rooted Poblenou’s cooperatives were in the physical space of the neighborhood. As a cooperative grew as an entity, so too did it grow physically; the acquisition of a building, and the expansion through the physical space of the neighborhoods, was thus an essential part of the growth of cooperatives. Usually, cooperatives began by renting a small space, and as they gained members and could expand their economic operation until they could finally buy a property in which to continue their activities – usually, this took 10-20 years. Owning a building meant that the cooperative was consolidated, and within these builds their might be a: café, theatre, warehouse, bread oven, and food shop. Once a cooperative had a space of its own, it could have greater stability and expand its offering of cultural and political activities.

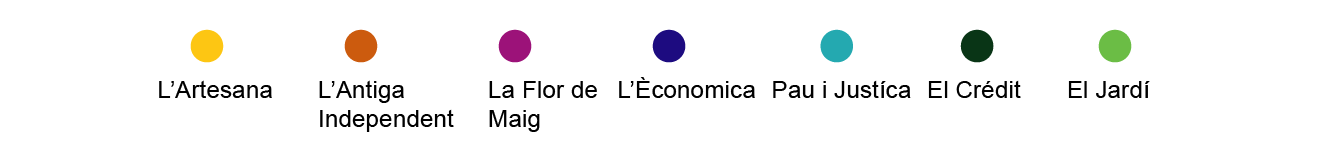

Cooperative movement over time. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Cooperative movement over time. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

An important distinction between cooperatives and other collective organizations was their recognition by the state. While some cooperatives were founded in the late to mid-19th century they were first formalized in 1887 by the Llei d’Associacions (Associations Act). The cooperative movement took off following the first Catalonian assembly of cooperatives in November 1898. In June 1899, representatives from 4 Poblenou cooperatives attended the first meeting of the Congrés Cooperatiu Catalano-Balear (Catalan-Balear Cooperative Congress) which set into motion the expansion of the cooperative movement. In 1920, the Federació de Cooperatives de Consum de Catalunya (Catalonian Federation of Consumer Cooperatives) was established in Barcelona, eventually leading to a restructuring of the cooperative movement by province and linking in to the International Cooperative Alliance. The cooperative movement, after some negotiations, even had a stand at 1929 International Exhibition in Barcelona, a moment that illustrates their relationship to the state.

The Cooperative Movement presents at the International Exhibition. Source: Marc Dalmau

Though not explicitly political, the cooperatives were inherently ideological spaces. They were nearly always founded by local working-class people for other working-class people in the neighborhood, and functioned as sites of sociability for these people. It was at these collectives that neighbors would gather to eat and discuss problems that arose in their workplaces, therefore building a sense that they were partners and not alone in their material conditions. Marc Dalmau cites a statement from cooperative leader Juli Blaquer suggesting it best to “Let the consumer make the economic revolution; let justice pass through the fields of economics.” Cooperatives created alternative economic relations that engendered alternative social relations.

(squares follow same color code but indicate associates)

(squares follow same color code but indicate associates)

Associates who lived near cooperatives. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Associates who lived near cooperatives. Basemap source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Many leaders in the cooperative movement saw their role as simply creating spaces outside of capitalism and the state but did not necessarily connect that to a political vision for the world like that of the anarchist organizers. While the cooperatives were primarily constituted by working-class people, the leaders of the cooperatives sometimes middle-class people with very different, more individualistic goals. Furthermore, since cooperatives were recognized by the state, they did not operate in the context of illegality that much of the anarchist organizers did. Still, the cooperatives did sometimes support the labor movement. In 1919, for example, the cooperatives supported La Canadenca strike by providing food for striking workers that lacked both wages and food.

Building facades and cultural events of various cooperatives. Background color indicates cooperative (see legend above).

During the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923-1931), when there was a major crackdown on leftist organizing, the cooperatives played an important role in continuing the the politicization of working-class neighborhoods. Anarchist activists turned to organizing within some of the cooperatives, and cooperatives sometimes organized food collections for incarcerated activists and their families. Since cooperatives increasingly operated through direct democracy, the alternatives they created often aligned with anarchist principles without being explicitly anarchist.

Revolution

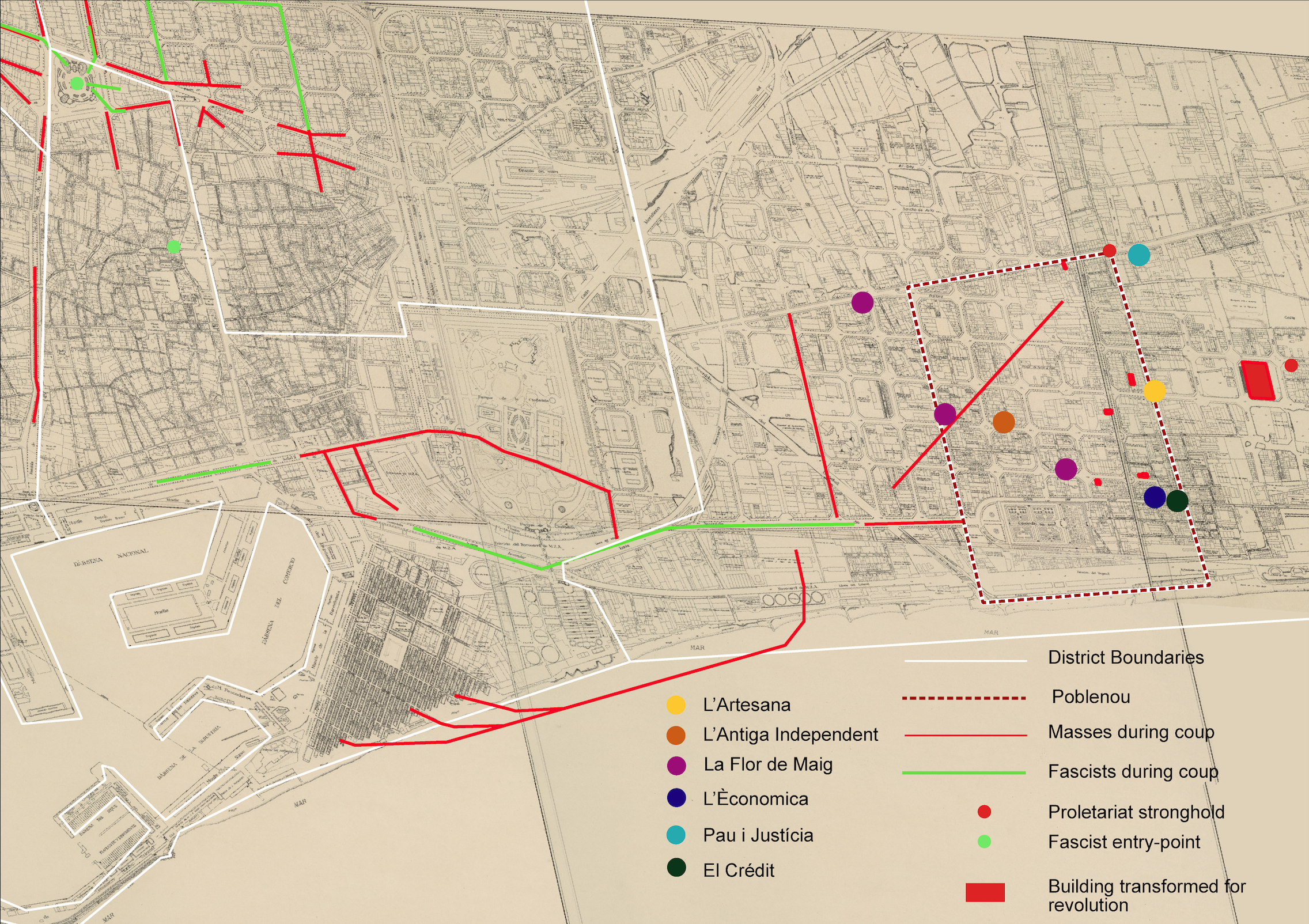

Map Illustrating the Events of the Coup (red is proletariat, green is fascist). Source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

Map Illustrating the Events of the Coup (red is proletariat, green is fascist). Source: Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya

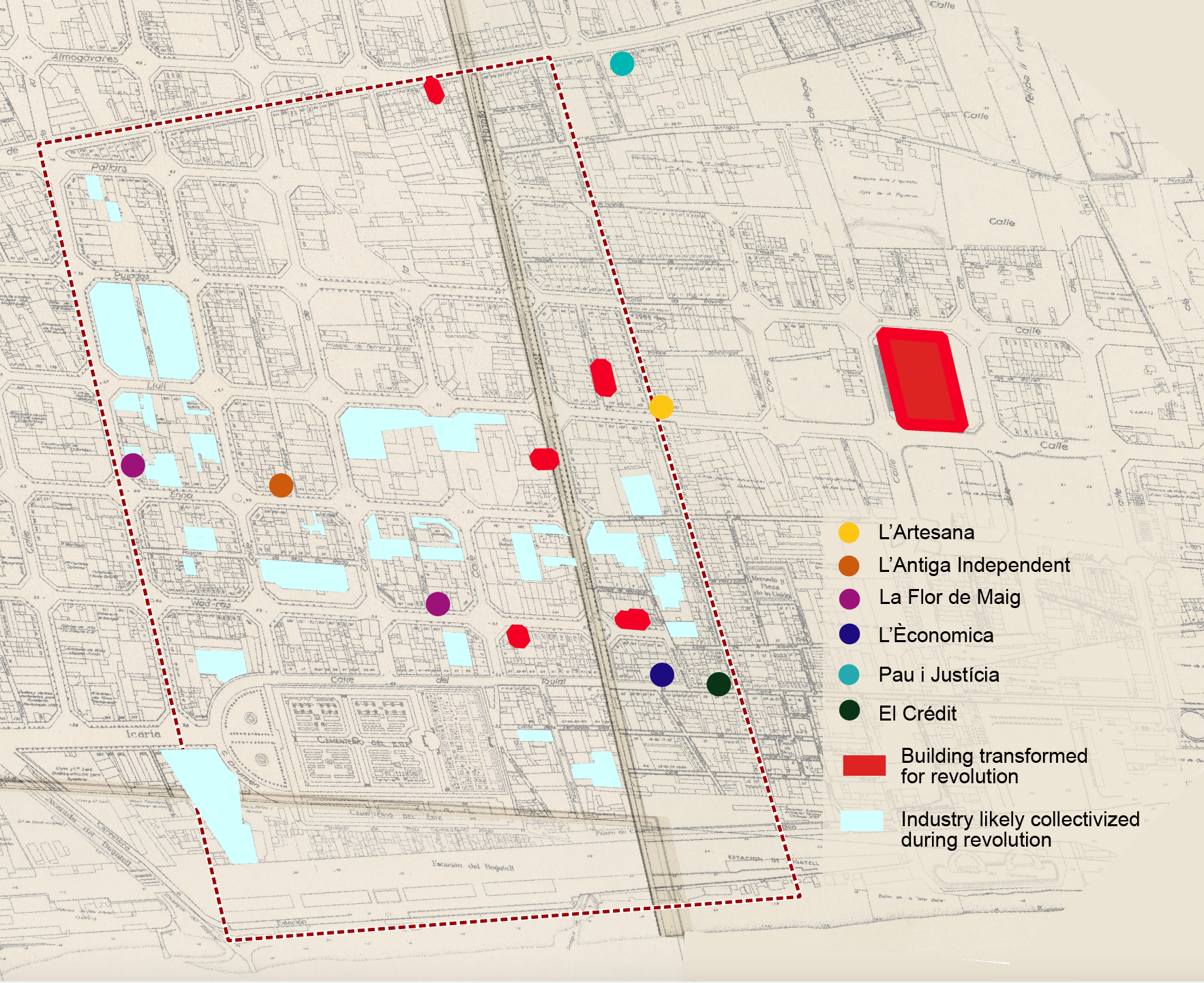

Poblenou’s cooperatives played a significant role in fighting off Francoist forces. They stored arms, held meetings, and provided food for anarchist organizers. The fighting that occurred at the beginning of the coup required a particular understanding of urban space that the cooperatives were well-equipped to provide.

Poblenou during the coup.

Poblenou during the coup.

The following editorial in the cooperative press describes the cooperative movement’s relationship to anarchist collectivization:

Our movement is certainly not a political or trade union organization, and therefore does not have the control of its affiliates to take an active and direct part in mobilizing citizen militias. But (…) From the very first moment, our cooperatives became centers of supply of the militias, inside and outside the capital. (…) Our ovens have worked tirelessly so that everyone will have bread. The stocks of condensed milk, hams, sugar, coffee, etc., and in general all the essential items, almost ran out the first days of the struggle, without considering the difficulties of having to replenish them later (…) Our entities that so many associates had and still have arms to their arm in the street have been able to fulfill their duty, as anti-fascist bulwarks, as peace outposts and as proletarian institutions, created for the people and sustained by the people. (…)

The cooperative movement thus materially supported the collectivization of Barcelona that occurred in 1936 but were in no way leaders of it.

The cooperatives stored arms for anarchist militants during the coup. Source: Marc Dalmau

Buildings collectivized during the war.

Buildings collectivized during the war.

Conclusion

Cooperatives created spaces outside of capitalist exploitation for working-class people. They were built around a sharing of goods, worked to limit hierarchy and utilize collective decision-making, and strove to prioritize social relations even at the cost of efficiency. In examining these cooperatives, we see continuity in anti-capitalist alternatives despite immense political change. Spatially, it is clear that cooperatives transformed the neighborhood and set the stage for the 1936 revolution. To create cooperative organizations, mutual aid networks, and community hubs is to plant the seeds for a future beyond and against capitalist exploitation and state violence.

Citations

Author unknown. 1930. English: 2 Posters of the Spanish Civil War. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/spain-civil-war-anniversary/oQGuG86r_WgJUg. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2_posters_of_the_Spanish_Civil_war.jpg.

“Barcelona (Barcelonès).” n.d. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://cartotecadigital.icgc.cat/digital/collection/catalunya/id/2335.

“Barcelonès.” n.d. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://cartotecadigital.icgc.cat/digital/collection/catalunya/id/2207.

Dalmau, Marc. 2015. Un barri fet a cops de cooperació: el cooperativisme obrer al Poblenou. La Ciutat Invisible Edicions.

Dolgoff, Sam, ed. n.d. The Anarchist Collectives:Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/sam-dolgoff-editor-the-anarchist-collectives.

Ealham, Chris. 2005. Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona, 1898-1937. Routledge. https://web-a-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAyNXhuYV9fMTA2MDAyX19BTg2?sid=3aa88506-0fba-4829-96cb-30eff0e8eb2c@sdc-v-sessmgr02&vid=0&format=EK&rid=1.

Federici, Silvia, and Peter Linebaugh. 2019. Re-Enchanting the World : Feminism and the Politics of the Commons. Kairos. Oakland, CA: PM Press. https://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?qurl=https%3a%2f%2fsearch.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dnlebk%26AN%3d1894652%26site%3dehost-live%26scope%3dsite.

Goldberg, Claire. 2021. “Urbanization & the Commons: An Anarchist History of Barcelona.” New York: Columbia University.

González, Albert Balcells i. 2017. “Collectivisations in Catalonia and the Region of Valencia during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939.” Catalan Historical Review, September, 77–92.

“Gràfic del moviment facciós a Barcelona: 19 de juliol del 1936.” n.d. Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya. Accessed April 13, 2021. https://cartotecadigital.icgc.cat/digital/collection/catalunya/id/2207.

Leval, Gastón, and Vernon Richards. 2018. Collectives in the Spanish Revolution. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

“Plano industrial y comercial de Sn. Martin de Provensals.” n.d. Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya. Accessed February 11, 2021. https://cartotecadigital.icgc.cat/digital/collection/catalunya/id/3152/rec/76.