The Ma’dān Tribes of Iraq: A case for Environmental Refugees

Swamp-dwellings Madan in the Hor by Georg Gerster. Science Source 1973

Introduction

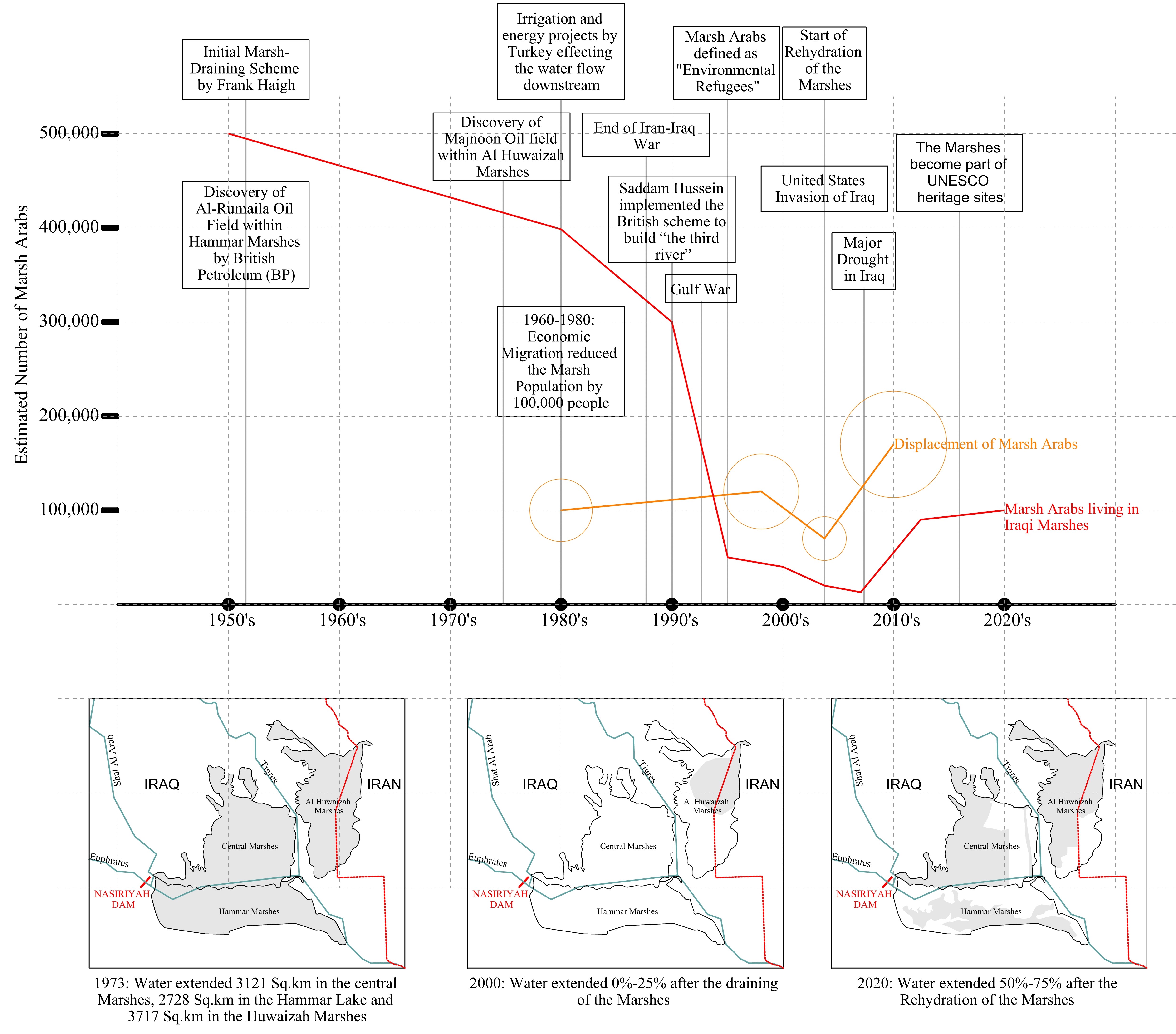

Once known as the largest wetland system in Western Eurasia, the Iraqi marshlands consist of distinct but adjacent marshes, the Central Marshes, Hawaizah Marshes and Hammar Marshes, providing habitats for several Marsh Arab tribes and a variety of non-human populations. Located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Southern Iraq, the marshlands are aquatic landscapes that are historically inhabited by the Marsh Arabs, also known as Ma’dān. Living in homes on floating islands, both made up of reeds, the livelihood of the Ma’dān consisted of fishing, rice cultivation and breeding livestock, and was highly attuned to flood environments of the marshlands. The unique geographical location of their habitat, however, made them vulnerable to exploitation for military, political and economical gain, through agricultural irrigation and oil exploration within the country as well as hydro-infrastructural operations in neighboring countries. Since the 1950s, an estimated number of 500,000 Marsh Arabs or Ma’dān have been marginalized, through the process of modernization, eliminating the way of life that they have relied on for decades.(Nicholson and Clark, 2003)

Reed houses, Iraq marshes 1978 by Paul Dober is licensed with CC BY 3.0.

Since the early 1990’s, the constant draining of the Marshes through the construction of dams, warfare and droughts, radically altered the environment of the Marsh Arabs. This placed the Ma’dān under constant threat of forced migration, leading to their internal displacement within Iraq, or movement to refugee camps mostly within Iran. In May 2001, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) published a report titled “Mesopotamian marshlands: the demise of an ecosystem”, which states that “given that the flight of Marsh Arabs was triggered by massive environmental deterioration, there is a strong case for them to be considered as Environmental Refugees.”(Partow, 2001) Prior to that, in 1994 the UNHCR provided a case for the displacement of the Marsh Arabs to be labelled as “Environmental refugees”. Since the 1980’s the term “Environmental Refugees” have been popularized to link the issue of environmental change with human migration. The use of the term “Environmental Refugees” to define the migration of the Marsh Arabs, has been used prior to the debate on the legal use of the term “Environmental Refugees” by many policy makers.

The Marsh Arabs or Ma’dān

The Marsh Arabs or Ma’dān have been natives to the Marshes prior to the demarcation of Iraqi borders by colonial Britain. The categorization of the Marsh Arabs, as a distinct marginalized community, was brought about through the process of colonization and modernization of Iraq. Since the British-led modernization schemes of Iraq in the 1950’s, the Marsh Arabs or Ma’dān’s habitat and ecosystem has been a target for draining to give way to infrastructural development such as the Al Nasiriya Dam and Al Rumaila Oil Field. the British controlled Iraq Petroleum company, produced films and imagery that depicted southern Iraq, where the Marshes are located, as a “living reminder of the past’’. This depiction of the marshlands and its inhabitants, were adjacent to images of hydro-infrastructural projects and oil refineries. The word “Ma’dān” was synonymous with “pre-modernity”, and hence they were forged in the development imagination of a nascent Iraqi state and its alliance with western consultants.

An accurate count of the population of the Marsh Arabs in Southern Iraq, historically and currently have not been done. Internally displaced people are more difficult to count than refugees who cross borders. The British NGO AMAR, formed to provide aid to Marsh Arab refugees, estimated that half a million people lived within the Marshlands prior to its draining in 1991. By the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, the Human Right Watch estimated that there were 250,000 Marsh Arabs remaining within the region. During the Iran-Iraq war, the marshes were turned into a battle zone. Iranian troops used the Marshes to penetrate into Iraq. Shi’a troops in the south of Iraq rebelled against Saddam’s government, and used the Marshes as a hideout place. The Marshes were therefore, subject to the regime’s retaliation, and constant bombings(Adriansen, 2004). By 2003, UN reported that around 10,000 Marsh Arabs remained, while 100,000 or 200,000 were internally displaced and 100,000 left the country as refugees to nearby refugee camps in Iran (such as the Servestan and Khuzestan camps). Furthermore, a severe drought in 2008, led to further depletion of the Marshes.

Timeline showing migration trends of Marsh Arabs along key events Click here to view full screen

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A

Drainage of the Marshlands

The Marshlands have held a strong ecological significance in Iraq’s history beginning from the country’s process of modernization in the 1950s, the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s, through the tumultuous presidency of Suddam Hussein in the 1990s, and into the current instability of the region.

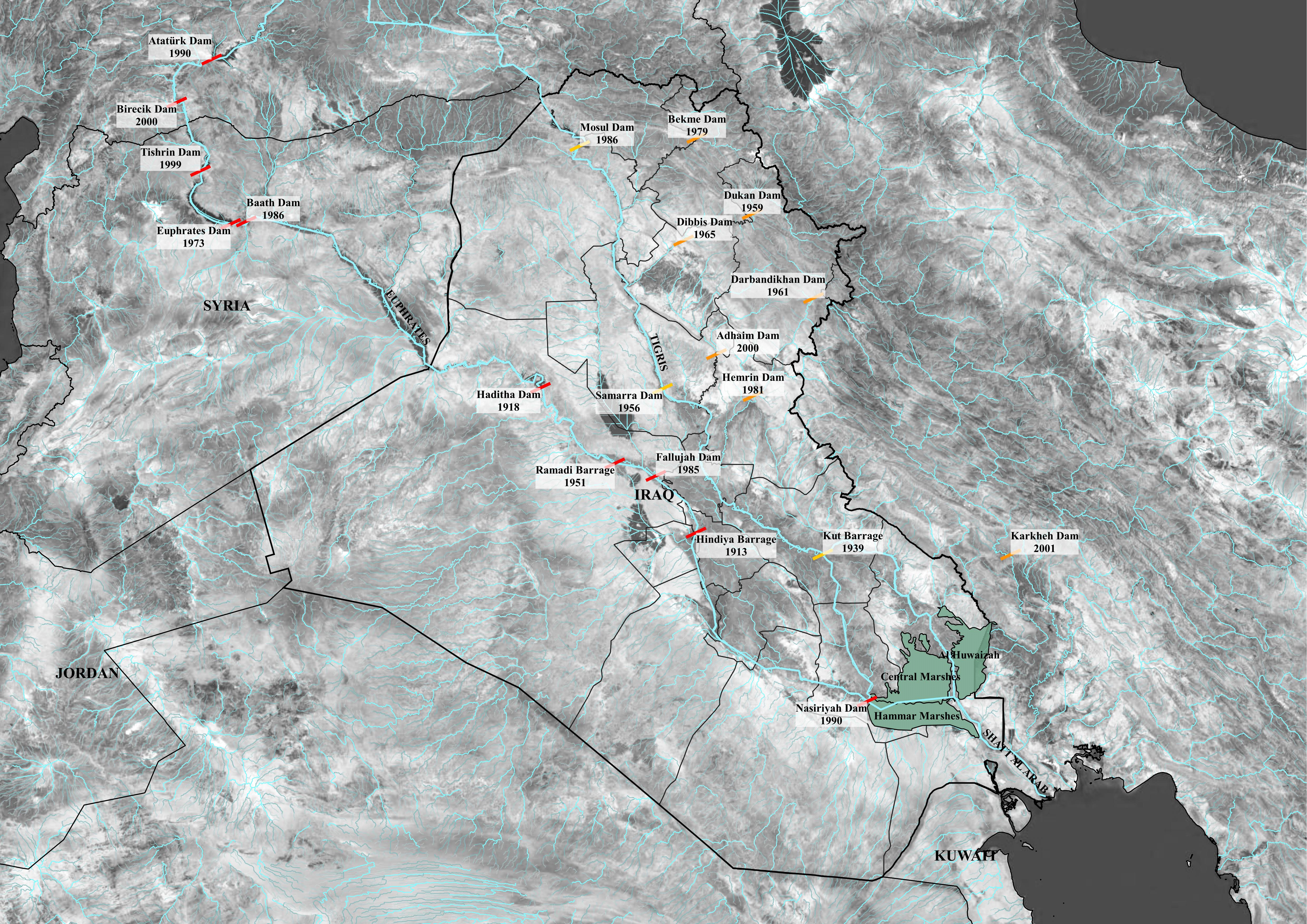

The Marshlands key location between the Tigris and Euphrates River basins made it susceptible to the process of modernization brought on by the development of several dams for hydroelectric power both within and outside the Iraqi borders. Since the 1950s, developments like these have placed several Ma’dān tribes under constant threat of relocation as changes of flow from both the rivers affect the overall water levels and vegetation within the marshes. Several dams built within Iraq, and its neighbouring countries, Syria, Turkey and Iran, affect the water flow to the marshes. The dams were built either for irrigating agricultural land, flood control, or hydropower. The map below identifies the several dams that were built along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers since the 1950s that have had direct effect on the Marshlands and it’s tribes. The marshlands continued to be targeted for draining in the 1970’s to ‘reclaim’ the wetlands for agricultural irrigation purposes. Since the 1980’s, Turkey prioritized hydroelectric development, as well as combined the building of the dams in a giant irrigation and energy project called GAP. This project affected the water flow to downstream countries which in turn resulted in the decrease of the water level within the Iraqi Marshland.(Adriansen, 2004)

Map of Dams built along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Click here to view full screen

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A

Matrix of Dams along the Euphrates and Tigris that have direct effect on the Marsh water levels. Click here to view full screen

Source: Microsoft Bing product screen shot(s) reprinted with permission from Microsoft Corporation. © 2021 Maxar

Environmental conditions within the marshlands reached its worst during the presidency of Suddam Hussein who used water control from the rivers as a political tool. Based on a design to construct a Third River by British engineer Frank Haigh in his Haigh Report for the Iraqi Government in 1951, a 565 km long canal (known as the Nasiriyah Drainage Pump Station) between Euphrates and Tigris was constructed during the 1990s in order to desalinate the Euphrates water, effectively draining water from the Central Marshes into the Persian Gulf. By the end of the decade, nearly 90% of the Marshlands were depleted, with only a partly intact region between the Iran-Iraq border remaining as it was fed by river flows beyond Iraqi control, making the marshes unable to sustain the livelihoods of the Ma’dān tribes (Adriansen, 2006).

Nasiriyah Drainage Pump Station. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although deliberate acts of aggression by the Iraqi government drained the economy of the Marsh Arabs, this was not the only factor that contributed to the displacement of the Marsh Arabs. The construction of dams upstream, warfare, droughts, oil extraction or the contamination of water due to chemical warfare agents all contributed to the displacement of the Marsh Arabs. False colour Landsat composite imagery below show the progression of drainage on the marshes till their almost complete depletion by 2000.

False Colour Landsat Imagery showing the drainage of the Marshlands from 1985-2000.

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A. Image Source: Landsat-5 and Landsat-7 images courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A. Image Source: Landsat-5 and Landsat-7 images courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

However, the depletion of the marshlands was used as a political tool by the United States Government as justification for the invasion of Iraq. One of the seven crimes for which Saddam Hussein was charged with was what the United States government referred to as the “genocide of marsh residents” and the destruction of the Iraqi marshes. What followed was the discussion of the “environmental” restoration of the Marshes which was essential to the narrative of US imperialism.(Guarasci, 2011)

The Displacement of the Marsh Arabs: A case of Environmental Refugees

The term “Environmental Refugees” was first popularized by Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute in the 1970s, and further developed by El-Hinnawi (1985) and Meyers & Kent (1995), among others.

-

People who had to leave their habitat, temporarily or permanently, because of a potential environmental hazard or disruption in their life-supporting ecosystems.

El-Hinnawai (1985) -

Persons who no longer gain a secure livelihood in their traditional homelands because of what are primarily environmental factors of unusual scope.

Meyers & Kent (1995,18)

Furthermore, El-Hinnawi describes three main types of environmental refugees

- Those temporarily dislocated due to disasters, whether natural or anthropogenic.

- Those permanently displaced due to drastic environmental changes, such as the construction of dams

- Those who migrate based on the gradual deterioration of environmental conditions.

Unlike the term “refugee” which has been internationally recognized during the 1951 UN convention, the categorization of “Environmental Refugees” has been contested and to date has no legal standing. Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) are explicitly excluded as refugees, since refugees lack protection from their state and therefore seek international aid. In some cases “Environmentally Displaced People” may seek protection from their state (Westra, 2009). The Marsh Arabs were both internally displaced within Iraq, or were moved to refugee camps in Iran. The significance of a legal definition for the displacement of the Marsh Arabs, was important in order to gain international aid, since they lacked the protection of the state.

There was one exception by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for the categorization of “Environmental Refugees” ; “ when acts of environmental destruction, such as poisoning of wells, the burning of crops, or the draining of marshlands are methods purposefully used to persecute, intimidate or displace a particular population” (Falstom, 2001). Therefore, under this exception the Marsh Arabs were one of the few cases that were labelled with the contested term of “Environmental Refugees”.

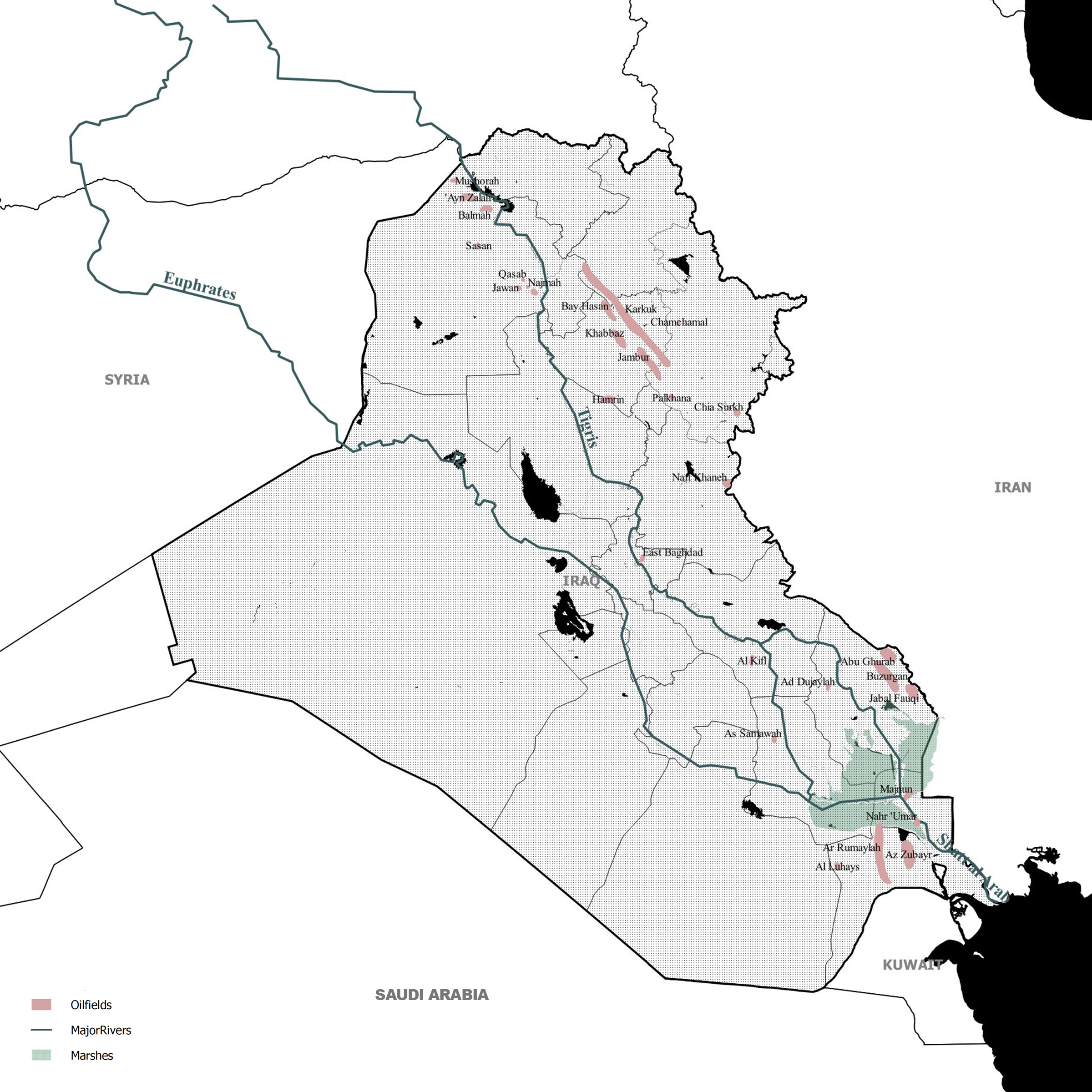

Even though the terminology is important in addressing the degradation of an ecosystem, as a result of human actions, the Refugee status does not address the root cause of the degradation that led to the migration of its human and non-human inhabitants. The exception within the terminology of “Environmental Refugees” was used by the United Nations as a tool to provide evidence and justification for international involvement within Iraq’s economically valuable resources. The UN conventions fail to mention that beneath the Marshes lay several “supergiant” oil fields. Since the Marsh Arab’s recognition as Environmental Refugees, the community has been displaced within refugee camps, and their current status is little known. The Marsh Arabs lack both the right to their indigenous land and water, and the legal status to object to the oil extraction within the territories they inhabited for thousands of years.

International Interest

In the early 2000s, restoration efforts for the wetlands were being advocated by many Iraqis in exile. Initiatives like Green Iraq campaigned for the reflooding of the marshlands through the destruction of dams built by Hussein, in the hope to revitalize the lost ecosystems and bring about the re-entry of the Marsh Arabs into the wetlands.

In her dissertation, ‘Reconstructing life: Environment, Expertise, and Political Power in Iraq’s Marshes’, Bridget Lauren Guarasci, Ph.D. and Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Frank and Marshall College, identifies how the restoration initiative by Green Iraq began receiving international funding once the Marshes were titled as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and how international ecological surveying by UNEP of the site created data and maps that began to attract private sector stakeholders in the process of conservation.(Guarasci, 2011)

Maps like the ones below show the increase in number of oilfields in the country since the US led occupation. They highlight unique locations of ‘supergiant oil fields’ in and around the Marshlands, which drew a lot of funding from international oil companies like Shell and Exxon Mobil in the hopes to get access to the oil resources through conservational attempts.

Oilfields in Iraq, 1993. Click here to view full screen

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A

Oilfields in Iraq during talks of marsh restoration, 2003. Click here to view full screen

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A

Al Huwaizah Marsh : A closer look at restoration efforts

As mentioned earlier, several international organizations participated in the efforts to restore the marshes to their former glory. The location of oil fields within the marshes led to peculiar partnerships between conservation organizations and international oil companies that wanted access to the resources in the region.

Sources: BBC, France24, Wall Street Journal, IUCN, Wetlands International

The Majnoon Oil Fields located within the Hawaizah Marshes is the world’s third largest. In 2009, UK’s Royal Dutch Shell and Malaysia’s Petronas Oil companies were awarded a license for a joint venture to operate the Majnoon Oil fields. By 2011, Shell had partnered with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Wetlands international to ensure that oil and gas development on the Majnoon oil field would not cause further damage to the marshlands.

Oil extraction locations within the Huwaizah and Hammar Marshes.

Image Source: Microsoft Bing product screen shot(s) reprinted with permission from Microsoft Corporation. © 2021 Maxar

Satellite imagery today shows that the marshes have been re-flooded to almost 70% of their original size. The False Image composite time lapse below shows the process of restoration over the decades of the 2000s till today. It may seem that restoration efforts were successful to bring back enough water into the marshlands to re-introduce ecological biodiversity and socio-economic activities of Marsh Arabs. However, that is not the case.

False Colour Landsat Imagery showing the ‘restoration’ of the Marshlands from 2000-2020.

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A. Image Source: Landsat-7 and Landsat-8 images courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A. Image Source: Landsat-7 and Landsat-8 images courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

A report published by the United Nations Integrated Water Task Force for Iraq in 2011 focused primarily on the restoration of the Marshes and stated that the conservation efforts needed ‘to go hand in hand with social and economic development, ensuring sustainable livelihoods for the people of the Marshlands’. However, most of the economic development within the marshes was brought on from oil exploration efforts within the existing oilfields. Since production of oil is water-intensive, and access to water within the marshes was already limited, oil companies began to use water injection infrastructure to increase pressure by using sea water. Even though partnerships like that between Shell and IUCN promoted implementation of socially responsible exploration measures, impacts groundwater and soil quality of the new water injection technologies had yet to be fully assessed at the time of their implementation. (UNIWTFI, 2011)

A recent study of the water quality in the Marshes in 2017, shows the high levels of salinity present within the marsh environment. Several factors contribute to these results, such as the limited flow of water from upstream projects, but also the introduction of groundwater into the marshes by oil companies in order to re-flood the marshes through their conservational efforts. Brackish groundwater increased the salinity of the marshlands consequently affecting the level of vegetation that is currently growing within the marshes.

Comparative Landcover Classification showing the reduction of marsh vegetation despite full re-flooding of the Marshes. Click here to view full screen

Imagery created by Alkhoury, F & Shetye, A

Comparative Landcover Classification of Al Huwaizah Marshes from 1985 and 2020 above shows the reduction of marsh vegetation despite full re-flooding of the Marshes . It becomes evident through this comparative study why we have yet to see proportional re-entry of the Ma’dān Tribes within the region despite almost 70-80% of the marshes being re-flooded. The conditions of the marshes today are unable to provide the quality of water and soil for the cultivation of vegetation and the rearing of cattle, both which are integral to the livelihoods of the Ma’dān tribes.

Conclusion

The geographical significance of the Marshlands of southern Iraq, has made the Marshes susceptible to the process of modernization, irrigation, warfare, drought and oil extraction. As a result the Marsh Arabs have become a marginalized community in Iraq leading to their forced displacement both internally within the country, and to refugee camps in Iran. Their early identification as Environmental Refugees did not render itself to be beneficial to the Marsh Arabs due to the unclarity of the terminology. The term ‘Environmental Refugee’ was instead used as a tool to pave a path for international intervention disguised as restoration attempts to gain access to valuable resources within the marshlands. The categorization of Marsh Arabs as ‘Environmental Refugees’ meant that the solutions leading up to the restoration of the Marshes were environmental in scope, aiming to bring back water to the territory through the process of oil exploration. Consequential effects of the process led to unfavorable environmental conditions that have been unable to sustain fishing, cultivating and rearing practices of the Marsh Arabs proving the disproportionate re-entry of the Marsh tribes to the Marshes despite its reflooding. Although important to address effects of climate change and environmental degradation on communities, the terminology of ‘Environmental Refugee’ does not address the question of stewardship and indigenous right to land and water, leaving the interest and rights of the Ma’dān over the territory they inhabit to be second tier to the interests of larger global parties.

References

- Adriansen, Hanne Kirstine. What happened to the Iraqi Marsh Arabs and their land?: the myth about the Garden of Eden and the noble savage.(Copenhagen: DIIS.2004 )

- Adriansen, Hanne Kirstine. The Iraqi Marshlands: Is Environmental Rehabilitation Possible?. Papers and Proceedings of Advanced Geography Conferences. Issue 29. (2006) Pg 214.

- Bates, Diane C. Environmental Refugees? Classifying Human Migrations Caused by Environmental Change. Population and Environment 23. (2002) 465–477 . https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015186001919

- Clark, Peter, and Sean Magee, eds. The Iraqi Marshlands: A Human and Environmental Study. ReliefWeb. (AMAR, November 30, 2001) https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraqi-marshlands-human-and-environmental-study.

- El-Hinnawi, Essam. *Environmental refugees. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.1985.

- Guarasci, Bridget Lauren. Reconstructing Life: Environment, Expertise, and Political Power in Iraq’s Marshes . 2003-2007. Dissertation Abstracts International. Thesis (Ph.D.). (University of Michigan, 2011) pg 72-108

- Hasab, H.A., Jawad, H.A., Dibs, H. et al. Evaluation of Water Quality Parameters in Marshes Zone Southern of Iraq Based on Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Water Air Soil Pollution, Issue 231. (2020) Pg 183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-020-04531-z

- IRAQ DTM. Accessed February 24, 2021. http://iraqdtm.iom.int/.

- Partow, Hassan. The Mesopotamian marshlands: demise of an ecosystem. (Nairobi: UNEP. 2001)

- Nicholson, Emma, and Clark, Peter. The Iraqi Marshlands: a human and environmental study. (London: Politico’s Pub, 2001)

- United Nations Integrate Water Task Force for Iraq. Managing Change in the Marshlands: Iraq’s Critical Challenge. United Nations Integrated Water Task Force for Iraq.(2011). http://iq.one.un.org/documents/Marshlands%20Paper%20-%20published%20final.pdf.

- United States. United States and the Iraqi marshlands: an environmental response : hearing before the Subcommittee on the Middle East and Central Asia of the Committee on International Relations. House of Representatives, One Hundred Eighth Congress, second session. (Washington: U.S. G.P.O. February 24, 2004.)

- Westra, Laura. Environmental justice and the rights of ecological refugees. (London: Earthscan. 2009.) http://site.ebrary.com/id/10346844.