Geothermal Energy Potential in the Philippines

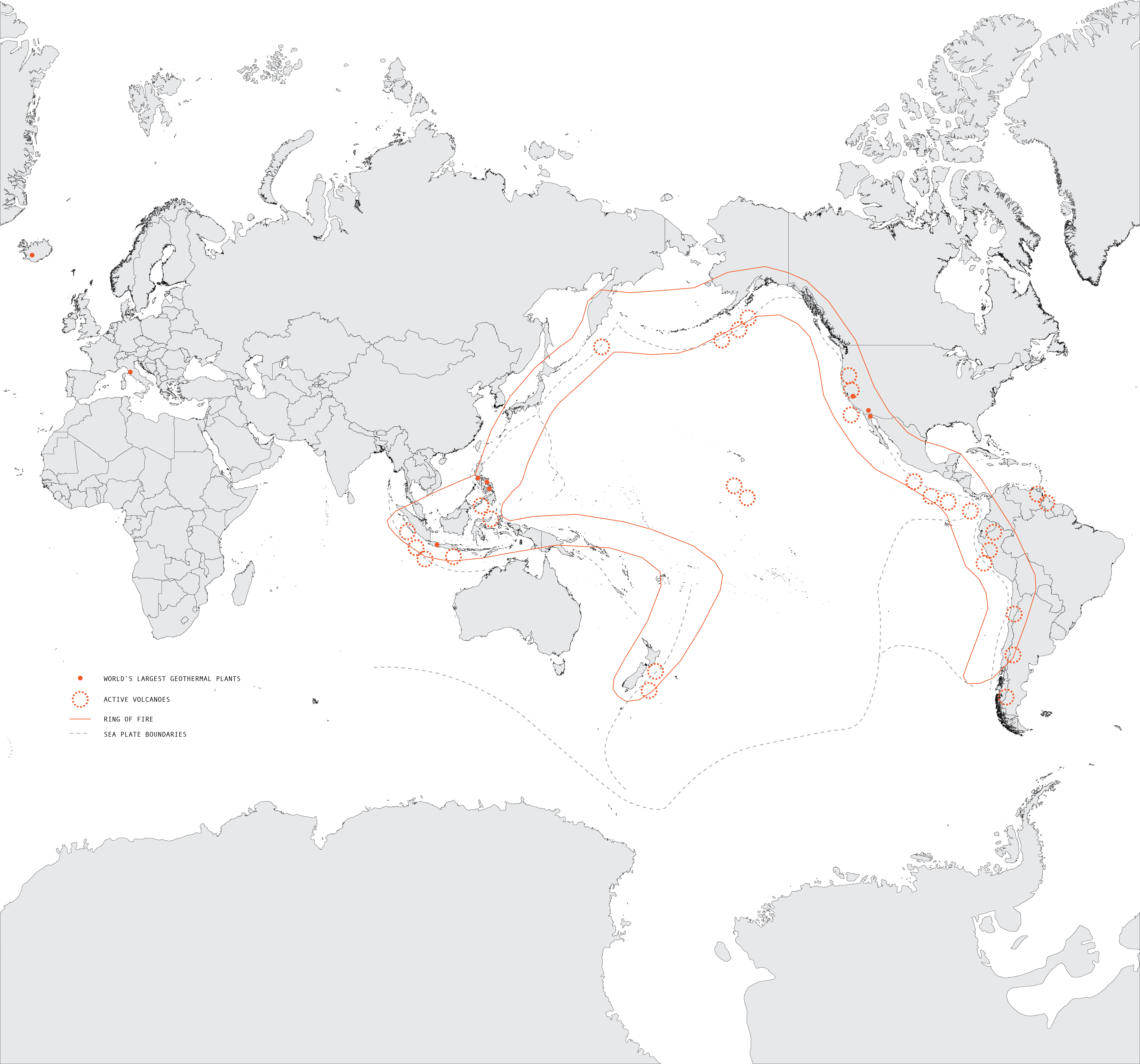

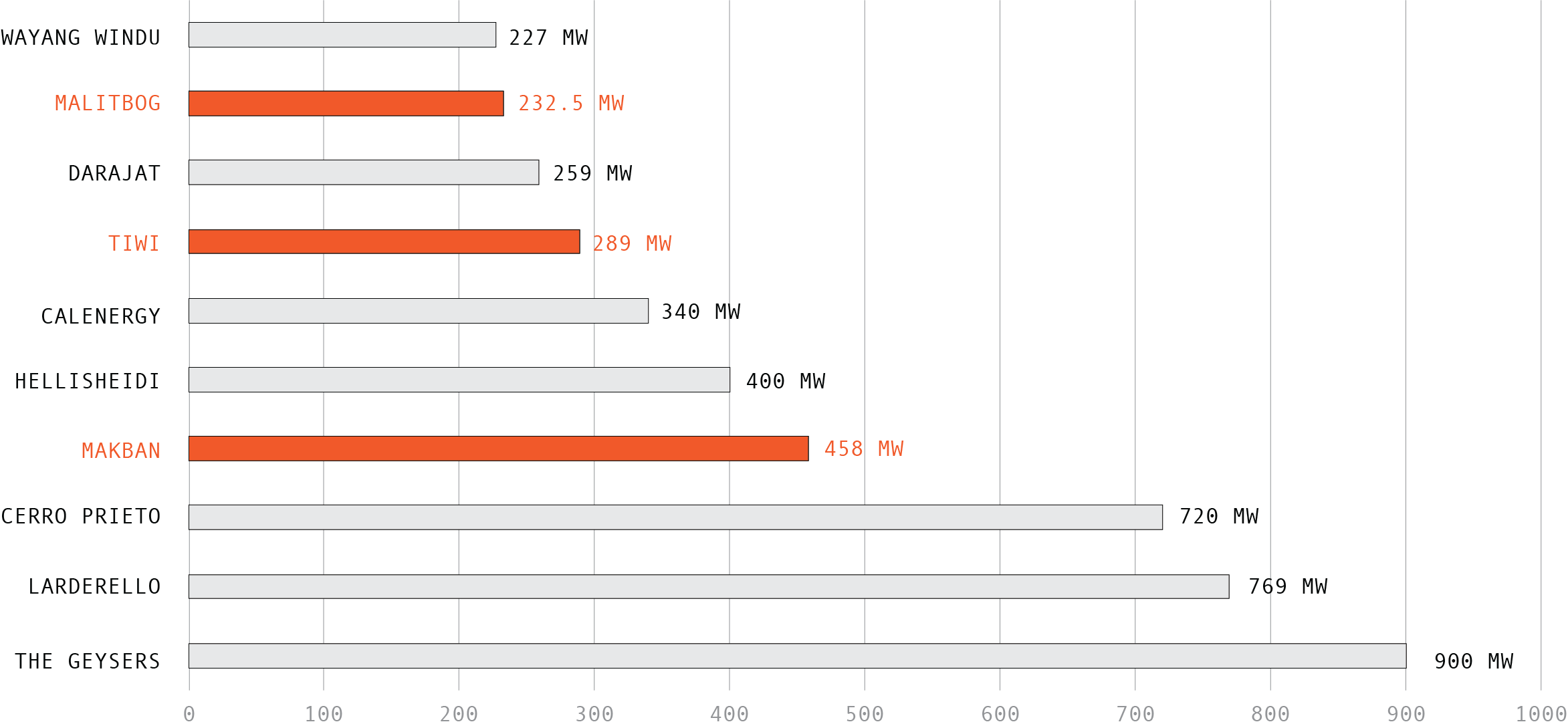

Today, geothermal energy infrastructure exists primarily at two scales: residential and large-scale industrial. The ten (10) largest capturing sites1 are located across the globe in North America, Southeast Asia, Iceland and Italy.

(1) 900 MW: The Geysers Complex (United States)

(2) 769 MW: Larderello Geothermal Complex (Italy)

(3) 720 MW: Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station (Mexico)

(4) 458 MW: Makban Geothermal Complex (Philippines)

(5) 340 MW: CalEnergy Generation’s Salton Sea Geothermal Plants (United States)

(6) 400 MW: Hellisheidi Geothermal Power Plant (Iceland)

(7) 280 MW: Tiwi Geothermal Complex (Philippines)

(8) 232.5 MW: Malitbog Geothermal Power Station (Philippines)

(9) 227 MW: Wayang Windu Geothermal Plant (Indonesia)

(10) 259 MW: Darajat Power Station (Indonesia)

8 of these 10 plants are located inside the 25,000 mile Ring of Fire, home to 75% of the world’s volcanoes and 90% of our earthquakes. Within this zone, the Pacific and Nazca plates border others, but it should be noted that the volcanoes within are not geologically connected.

Of these plants, 3 are located in the Philippines.

Volcanoes are responsible for the hilly topography and the Philippine archipelago as a whole, along with 80% of the planet’s surface.

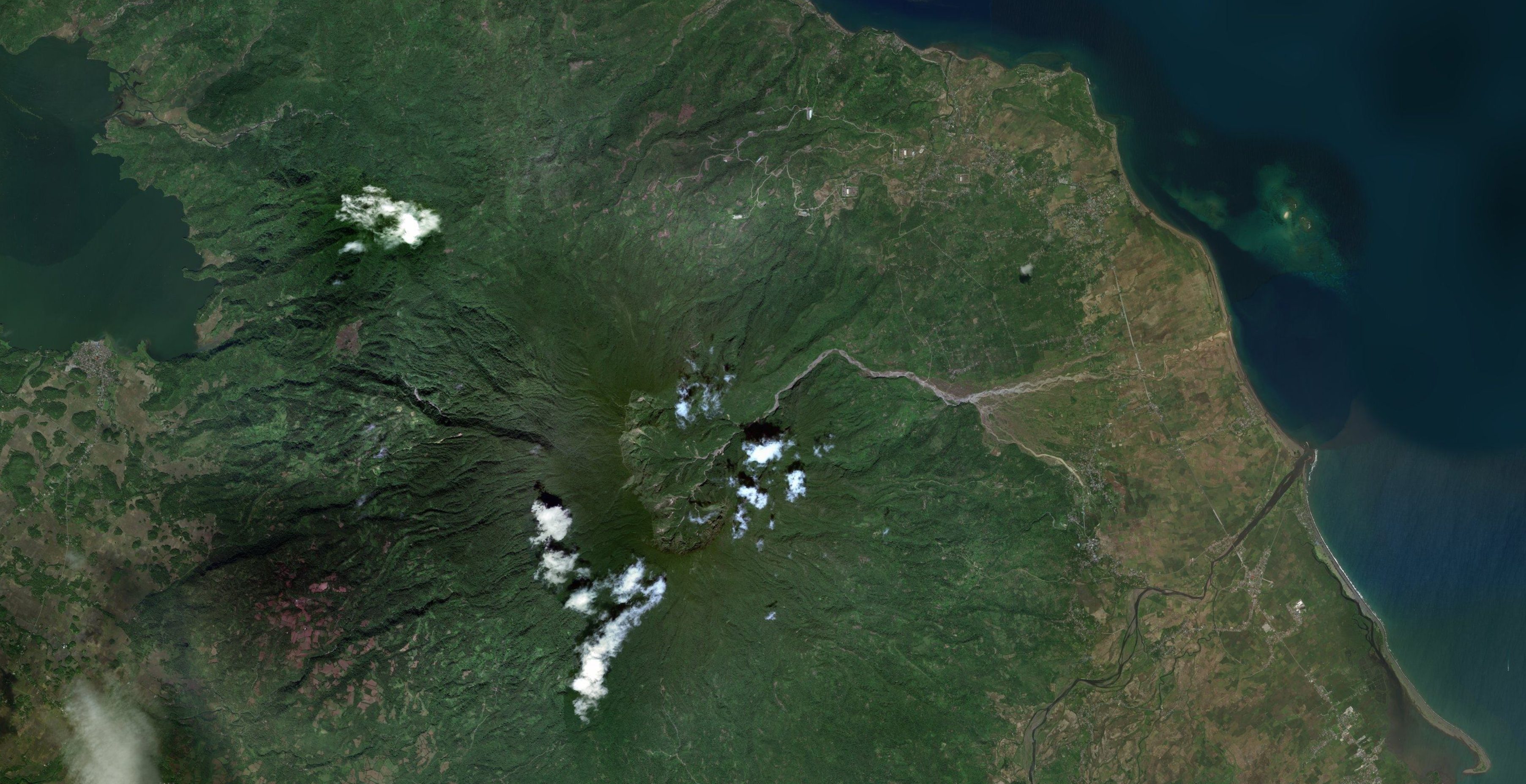

Home to more than 20 active volcanoes, the country is regularly at risk to natural calamity; prone to typhoons, earthquakes, mudslides, tsunamis, and floods due to its geographic and island characteristics.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to predict exactly when any volcano may erupt; sometimes allowing only a few hours notice. Located in a highly populated area, only 72 km (40 miles) from Metro Manila (the country’s major city centre), the Taal Volcano (the Philippines’ second-most-active volcano) erupted on January 13, 2020, almost 43 years after its last eruption in 1977.

Barangays within a 14 km radius around the volcano led to no initial reports of fatalities, but did cause approximately 25,000 people to be displaced.

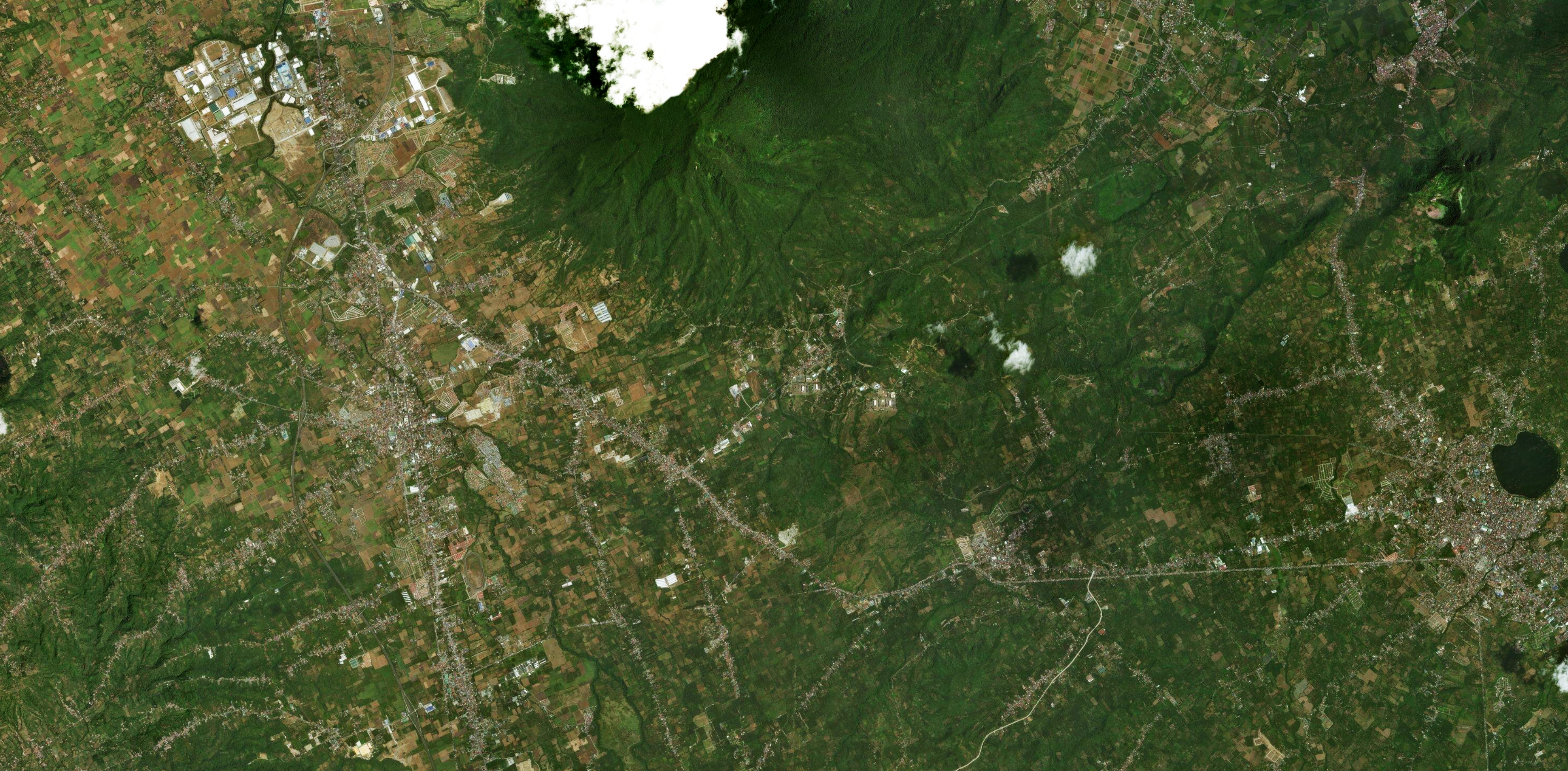

The largest of the Philippine geothermal plants, the Makban Geothermal Complex (also known as Makiling Banahaw), is located approximately 26 km from Taal Volcano, only 11 km outside of the 14 km evacuation zone.

It is located at the base of another volcano, Mount Makiling.

Upon further investigation, the other plants like the Tiwi Geothermal Complex, are also near active volcanoes.

The Tiwi Geothermal Complex is made up of 3 power plants with residential neighbourhoods adjacent and located 5 km northeast of Malinao Volcano (or Mount Malinao). Together with the Makban plant, they support 15% of the Luzon grid.

More than ¼ of the energy in the Philippines is geothermal energy, which takes advantage of its position on a geothermal hotspot.

What began initially as a response to the World Oil Crisis of 1973, the Philippines (under President Ferdinand E. Marcos) began developing geothermal infrastructure to decrease its dependency on imported energy and increase fuel cost savings. Since then, the Philippines has drilled over 900 wells throughout the country over the last 40 years. However, according to Benjamin Diokno, Economics Professor at the University of the Philippines, new energy infrastructure in the country has been neglected. A study by the Energy Regulatory Commission suggests that up to 72% of power plants are at least 16 years or older, contributing to the country’s vulnerability.

Exacerbated by the risk of natural disasters, we have already seen through catastrophic events like Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the storm not only killed thousands of people in a tsunami-like storm, but also tore the roofs off thousands of homes, including the roof of the Malitbog Station (which boasts the single largest roof of a geothermal operation in the world).

The damage as quoted in a New York Times article, exemplifies a broader paradox for the country,

“A storm consistent with some scientists’ warnings about climate change has done tremendous damage to an island that is one of the world’s biggest success stories of renewable energy, and to a country that has contributed almost nothing to the global accumulation of greenhouse gases.”

The country has set lofty goals to double its capacity by 2030 (only 10 years from now) or by at least 70% (according to Scott Roberts, Senior Investment Specialist of the Asian Development Bank). Experts say that this means that the country would need to add a capacity of 600 MW every year for the next 15 years to meet the country’s growing energy requirements. Like many developing countries, the Philippines faces a larger energy crisis with its aging infrastructure unable to keep up with the surging energy demands of the rapidly growing population, balanced with the global need and desire to do so without creating more harmful greenhouse gases.

We see this manifest today in the country’s persistent brownouts and blackouts, interrupting livelihoods and businesses for hours or sometimes days at the time, with populations outside of city centres at greater vulnerability. In March 2019, the Luzon grid saw a peak demand of 9491 MW against the grid’s available 10,115 MW; thereby leaving an operating margin of just 624 MW (short of the required contingency reserve of 647 MW).

Ramon Allan V. Oca, Undersecretary of the Philippine Department of Energy, suggests that the geothermal capacity expansion is unrealistic unless development is allowed in national parks; a foray that needs to be responsibly managed. However with many of these plants under private control, the long-term planning and permitting of these developments becomes increasingly crucial.

Citing a September 2018 PowerPoint presentation of Senator Sherwin T. Gatchalian, chair of the Philippine Senate’s energy committee, “the whole thing would require 359 government signatures, involving 74 agencies and bureaus, covering 43 different licenses and contracts,” shows light that bureaucracy alone may stifle any monumental development.

But it isn’t the country’s desire to be an export of this renewable energy that is at true risk, it is the needs of the communities that sit adjacent to these productions that needs more discussion.

With the suggestion that these plants continue working with the community so that “everybody benefits,” more community engagement and planning with stakeholders on the ground need to be happening now.

Sources

Achenbach, Joel. “Eruption of Taal in the Philippines Is a Warning about Global Volcano Hazards.” Washington Post, January 16, 2020, sec. Science. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/taal-volcano-in-the-philippines-is-a-warning-about-global-volcano-hazards/2020/01/15/30f1e9b8-36e1-11ea-bf30-ad313e4ec754_story.html.

Bradsher, Keith. “Font of Natural Energy in the Philippines, Crippled by Nature.” The New York Times, November 21, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/22/world/asia/font-of-natural-energy-crippled-by-storms-natural-energy.html.

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2019. “Geothermal Energy Factsheet.” Pub. No. CSS10-10.

Climate Care: The Heating & Cooling Professionals Who Care. “The World’s 10 Biggest Geothermal Plants,” January 25, 2016. https://www.climatecare.com/blog/the-worlds-10-biggest-geothermal-energy-plants/.

Gutierrez, Jason, and Hannah Beech. “Taal Volcano Eases, but Philippines Worries Worst Is to Come.” The New York Times. January 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/15/world/asia/taal-volcano-philippines.html.

Ichord, Robert F. “SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE WORLD OIL CRISIS: 1973,” n.d., 31.

Neuman, Scott. “Volcanic Eruption In Philippines Causes Thousands To Flee.” NPR, January 13, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/01/13/795815351/volcanic-eruption-in-philippines-causes-thousands-to-flee.

Wei-Haas, Maya. “Volcanoes, Explained.” National Geographic, January 15, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/natural-disasters/volcanoes/#close.