Off The Grid: A Spatial Exploration of the Historic Development of the Brooklyn Street Grid

Introduction

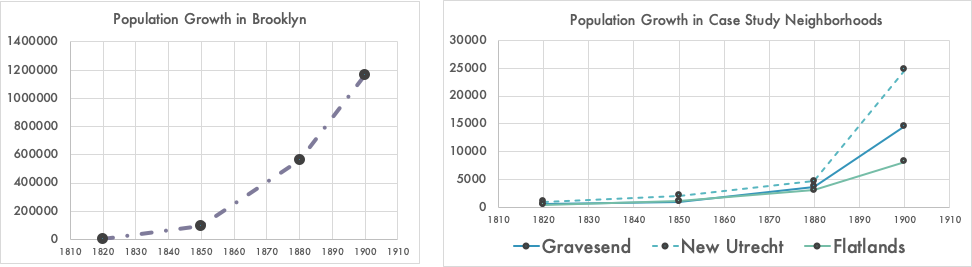

Today, it is hard to believe that Brooklyn was the heart of farming in the 19th century. The historic implementation of the Brooklyn street grid is the epitome of the transformation from rural to urban. Over the course of the mid-1800s to the early-1900s, the execution of street grid created development in the city of Brooklyn. This spatial project examines three outlying neighborhoods and major farming communities in old Brooklyn - Gravesend, New Utrecht, and Flatlands - and their relationship with the growing street network. This project aims to examine spatial pushes and pulls between historic farmlands and the actualization of the modern street grid from 1850-1910. The central research question for this project is: how have these neighborhoods either transformed or stayed constant in the implementation of the street grid?

Background

Following a massive increase in population in the late 18th century, New York consolidated its role as America’s leading city in the 19th century with a string of influential infrastructural and financial decisions in the face of historic socio-political events. In 1807, a steamboat route between New York and Albany spurred cargo and passenger movement. In 1825, the city completed construction of the Erie Canal–hence providing direct access to Atlantic Ocean trade routes and allowing the natural harbour of the city to be utilized in its full capacity. Impacted by the devastating Great Fire of New York in 1835 and motivated by the importance of increasing water supply, the city commenced service of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842. The economic developments in the 19th century also coincided with a period of increased immigration into the city, leading to not only a larger workforce, but also a more packed city. Although the prospect of an expanding population influenced the 1811 Plan that designed Manhattan’s famed rectangular and rigid street grid, the steeply rising immigration rates post the Civil War and tightly cramped tenements led to concerns that New York was reaching its density limits.

The economic success and infrastructural developments of New York also had a domino effect on Brooklyn’s own prosperity. As population rose in 19th century Manhattan, more and more New Yorkers looked towards Brooklyn, which was established as a city in 1834, as a residential alternative. The City of Brooklyn originally included the northwestern tip of the borough. In 1839, Brooklyn began to develop its own residential grid system. Bolstered by regular steam service, the eastern shore cities of Williamsburg and Bushwick became viable options to commute to workplaces in Lower Manhattan. Both cities later were annexed by Brooklyn in 1854. The growing shipping industry and the deepening of the Gowanus Canal provided Brooklyn with increased industrial access to the waterfront. Further links to New York were also established through sharing of utilities such as fire services and the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883.

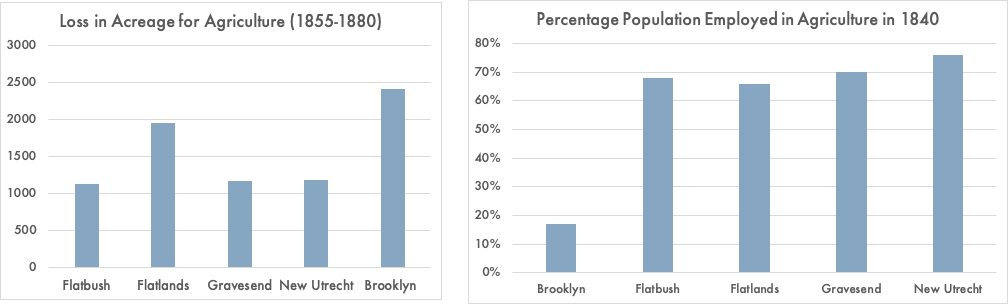

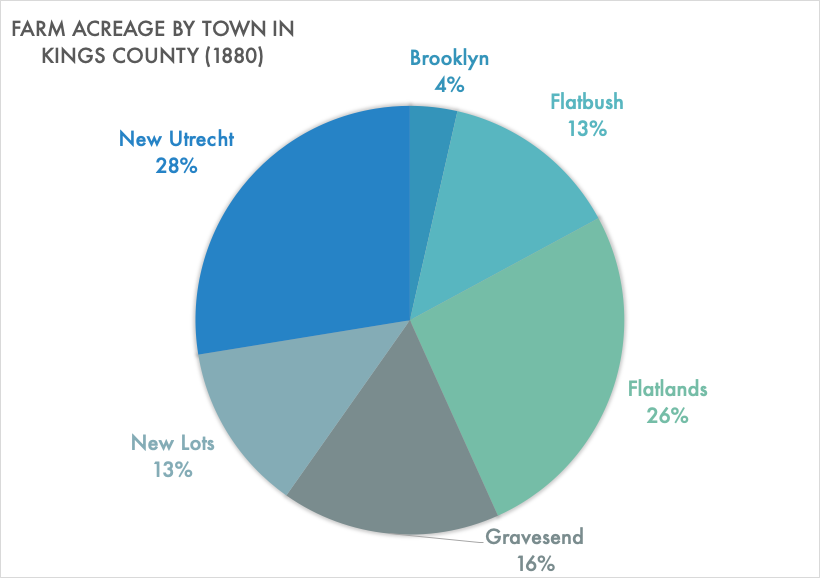

As the city of Brooklyn quickly industrialized, the rest of Kings County remained predominantly agricultural. As larger transportation networks were established towards the end of the 19th century, the county became further integrated despite its contrasting socio-spatial characteristics. This integration was only consolidated when neighboring towns were annexed in quick succession - New Lots in 1886; Flatbush, Gravesend, and New Utrecht in 1894; and Flatlands in 1896. This large expansion made Brooklyn’s city boundaries coterminous with Kings County before it’s subsequent consolidation into Greater New York in 1898.

While it’s status as a city was short lived, the simultaneous formation of residential and industrial Brooklyn as a response to the developments in Manhattan and the successive annexations of neighboring agricultural towns had important ramifications on the growth of the borough as a whole. Not only was there a tension between two distinctive ways of life– agricultural and urban–but this tension manifested itself spatially. As opposed to the close residential units and transport networks of Brooklyn pre-1886, the rest of the towns in Kings County consisted of sprawling farmlands. From a small residential street grid in the middle of the century to at one point in the late 1800s a much larger residential street grid surrounded by farm lines of the newly annexed agricultural towns – this conflict is best understood through Brooklyn’s street grid.

Toggle on and off layers on top right of map by double clicking to view street grid in 1850, 1880, 1910

Case Studies

The nature and topologies of these farming towns were undeniably similar. The populations in all of these small towns boomed after the 1800s while the amount of farm acreage alloted continued to decline. All of these small towns were centered around a small center (displayed below) and much of the coming development would try to incorporate these strong centers into orthogonal grids, and further, an infrastructural and spatial order. In 1850, these neighborhoods just consisted of centers and spokes–reaching out to other areas in Kings County. But by 1880, these neighborhoods and their surrounding areas were included in a county-wide grid plan. Finally by 1910, many of these plans were coming to fruition and these neighborhoods were getting filled in with people and buildings. The brief case studies below begin to show the intense neighborhood changes of the time.

Case Study 1: Gravesend

One of the first towns in what we know now as Brooklyn, Gravesend was one of the first towns founded by a woman (Stockwell 1884, 1). Established as a British colony in the 1600s by Lady Deboarah Moodly, Gravesend is located in the southern part of modern day Brooklyn and is known for its relationship to famed locations such as Coney Island and the Gravesend Cemetery established in 1650. In its founding, Gravesend was, of course, a primarily agricultural town. For the 200 years that followed the first arrival of British settlers, Gravesend’s agricultural characteristic remained remarkably consistent. Prior to 1850, Gravesend’s original square street plan was established and now consists of modern day Gravesend Neck Road and McDonald Avenue (Forgotten New York 2000).

During this intense agricultural period, Gravesend’s population barely grew. The 1835 Census stated an increase in population of only 635, which meant an increase of 427 residents over the preceding 97 years (Stockwell 1884, 15). In comparison, Brooklyn had a population of almost 7,500 in 1828, by 1840 that number had risen to more than 36,000 (Ibid). At the end of the century however, Gravesend witnessed a notable increase in population - reaching 3,500 inhabitants in 1880.

In 1850, the center of Gravesend was connected to other development projects in Kings County. Some of these projects included: the opening of the Coney Island Causeway in 1823, Gravesend Avenue in 1838, Coney Island Plank Road in 1849 (later known as Coney Island Avenue), Ocean Avenue in 1871 and Ocean Parkway 1876, which not only connected Gravesend to the City of Brooklyn, but the neighboring agricultural towns (Stockwell 1884, 16-18). By 1880, the neighborhood of Gravesend had filled in slightly primarily with attractions like Coney Island carnival infrastructure and jockey clubs and horse parks. The Brooklyn Jockey Club and the Coney Island Jockey Club disrupted the planned grid, but symbolized increased development in the neighborhood and a new type of capitalization on agricultural tools. By 1910, many of the planned streets in 1880 had been paved or in function, and there were more buildings expanding beyond the town center. While attractions like jockey clubs were present, there were plans to phase them out and the town center began to blend in with growing infrastructure.

Case Study 2: New Utrecht

First established in 1652, New Utrecht comprised the modern day neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Borough Park and Bay Ridge. Similar to other towns in Kings County, for most of its history New Utrecht was primarily farmland. Census data states that almost 80 percent of its inhabitants were involved in agriculture in 1840 (Linder and Zacharias 1999, 314). The center of New Utrecht was in southwestern Brooklyn by the Gravesend Bay, and consisted of a trisection of three historic roads, two from the colonial era: the Road from New Utrecht to Flatbush - today’s 18th Avenue; the southwest end of Kings Highway; and the Brooklyn, Greenwood and Bath Plank Road — which is now New Utrecht Avenue (Forgotten New York 2010).

In 1850, it is obvious that the center of New Utrecht formed around Brooklyn and Bath Plank Road and Kings Highway as it is situated right in the middle. The improvement of street car and railroad networks in the region–such as the opening of the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad in 1864–were important developments that connected the town to the rest of the county. By 1880, much of the surrounding area of the town’s center was actually filled in with paved roads and there is a clear densification of buildings. However, it’s relative distance from Brooklyn and lower expenses compared to the city’s municipal government ensured that for most of the 19th century opposition for annexation remained strong. It was only in 1894 when forced into consolidation by the state legislature that New Utrecht agreed to an annexation by Brooklyn (Williams 2014). By 1910, after the town was annexed by the city, it continued to experience more street paving and building construction

Case Study 3: Flatlands

Located in the southeast part of modern day Brooklyn, Flatlands was the last of the Kings County agricultural towns to be annexed by Brooklyn in 1896. Due to the location of the neighboring Jamaica Bay, Flatlands was valued for its advantages in rich agricultural land and was termed even at the time of annexation as “a farming town” and an “agricultural district” by the press (Linder and Zacharias 1999, 119). Unlike the other agricultural towns that experienced some level of increased transit connectivity over the span of the 19th century, Flatlands remained relatively underdeveloped infrastructurally and was dominated by farmland. While unopened, but present in 1850, the only exception to the lack of connection was the Brooklyn and Rockaway Beach Railroad, which opened in 1865 and ran through Canarsie in Flatlands (Ibid, 119). This lack of infrastructural connectivity also translated to a lower population density (Linder and Zacharias 1999, 117) than even Flatbush and New Utrecht. In 1850, the population per square mile in Flatlands was just 81 (Ibid, 117). Yet despite increased isolation and a small population, in 1850, the very center of Flatlands was self-sustaining with its own church and school.

While there was a planned grid for the Flatlands in 1880, it had more family-owned swaths of, most-likely, farm land than any other neighborhood in this analysis. The large presence of farming families was 0ne of the primary reasons for Flatland’s resistance to annexation as this town had a very powerful and wealthy farming population who were concerned about the extra costs (such as payment of utility services and higher tax payments) associated with citydom (Ibid, 160). As the movement to consolidate Brooklyn with the City of New York gained momentum almost simultaneously, those in opposition to Flatlands’ annexation also reduced in intensity (Zami 2015).

Ultimately, it was announced in 1894 that Flatlands would be annexed to Brooklyn. This decision, which went into effect in 1896, had a significant impact on Flatlands. Census records from Kings County indicate that the population in Flatlands almost doubled from 1890 to 1900, with particular growth observed in the years following the announcement (Ibid). By 1910, like the other towns, some of the planned grid had taken shape. Many roads surrounding the center of Flatlands had been paved and development sprawled across them. However, areas on the outskirts of the old town were planned and were still waiting to be developed.

Conclusion

As the heart of old Brooklyn’s agricultural business, these three towns underwent tremendous changes between 1850-1910, and even changed to modern day. In 1850, all of these three towns started as centers and connecting roads, which later would be incorporated into a planned grid, while not always orthogonal like Manhattan’s. However, despite the efforts to incorporate these towns after annexation in one all encompassing grid, it is important to recognize that each of these town centers exist today. Despite the industrial shift and residential boom of Brooklyn, these historic and strong town centers not only still have a presence in the contemporary grid but they also signify a level of spatial resistance on the part of the various agricultural towns of Kings County over the course of the 19th and early 20th century.

References

Text:

“Annexation and Consolidation – The Peopling of Flatbush.” Accessed May 10, 2020. https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/moses2015/2015/05/07/annexation-and-consolidation/.

“Gravesend, Brooklyn - Forgotten New York.” Accessed May 10, 2020. https://forgotten-ny.com/2000/05/gravesend-brooklyn/.

Linder, Marc, and Lawrence S Zacharias. Of Cabbages and Kings County : Agriculture and the Formation of Modern Brooklyn. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1999.

Stockwell, Austin Parsons. History of the Town of Gravesend, N.Y.,. Brooklyn, N.Y., 1884.

“The Heart of New Utrecht - Forgotten New York.” Accessed May 10, 2020. https://forgotten-ny.com/2010/02/the-heart-of-new-utrecht/.

Williams, Keith. “Brooklyn’s Evolution From Small Town to Big City to Borough.” Curbed NY, July 24, 2014. https://ny.curbed.com/2014/7/24/10069912/brooklyns-evolution-from-small-town-to-big-city-to-borough.

Mapping:

Columbia University GSAPP Center for Spatial Research. Brooklyn Streets. [shapefile]

Department of City Planning. Borough Boundaries [shapefile]. 1 January 2013, updated 2020.https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Borough-Boundaries/tqmj- j8zm

Department of Information Technology & Telecommunications. NYC Street CenterLine [shapefile]. 19 June 2012, updated 2020. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/NYC-Street-Centerline-CSCL-/exjm-f27b

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Atlas of the borough of Brooklyn, city of New York. Newly constructed and based upon official maps and plans on file in the Municipal Building and Registers Office (Hall of Records). Supplemented by careful field measurements and observations [1916-1920]” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1916 - 1920. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a4772020-c5f8-012f-2583-58d385a7bc34

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Atlas of the borough of Brooklyn, city of New York. The first Twenty Eight Wards complete in Four Volumes. Three additional volumes for the Four new wards will complete the entire borough. Volume One Embraces Sections 1, 2, 3 & 4. Volume Two, Embraces Sections 5,6&7. Volume Four Embraces Sections 12, 13 & 14. Newly constructed and based upon official maps and plans on file in the municipal building and registers office (Hall of Records) supplemented by careful field measurements and observations. By and under the direction of Hugo Ullitz, C.E. Published by E. Belcher Hyde. 97 Liberty Street, Brooklyn, 1903. Volume One.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 11, 2020. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/64b4acd6-f0f0-4e40-e040-e00a18063442

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “Robinson’s atlas of Kings County, New York : compiled from official records … [1890]” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 11, 2020. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ad5443a0-c604-012f-c182-58d385a7bc34

M. Dripps. “Map of Kings and part of Queens counties, Long Island N.Y.” Library of Congress. 1852.

Data:

Historic Census data. Accessed from - Linder, Marc, and Lawrence S Zacharias. Of Cabbages and Kings County : Agriculture and the Formation of Modern Brooklyn. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1999.