The Land of Sacred Waters: Hydropolitics in the Indian Subcontinent

The geography of the Indian subcontinent has been a function of mountains, plains and rich monsoons, that cradled and shaped the land, giving birth to a river system that feeds and enriches. Rivers “made the rich, fertile ground that allowed the emergence of agriculture and sedentary living” and “instigated the emergence of cities”. Since the advent of settlements, people have utilized the dynamism of the fluvial landscape - to obtain water, one of the most basic needs for survival, and also to fuel commerce, trade and economic advancements. To the people of the subcontinent, the rivers appear as gods, and their water seen as a boon that provided for their needs. These revered rivers shaped the land and cultures and were in turn transformed by their associations.

Aarti (licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Source: AnimeshHazra

The namesake for the Indian subcontinent, Indus, is believed to be one of the rivers that flow from paradise, giving birth to one of the oldest civilizations in the world. Rigveda reveres the indus as a mighty flow as for years settlements revolved around the seasonal changes of the river. The volatile nature of the river banks and the ever changing flow became an enemy to stable settlements. But as time passed and technology advanced, humans found themselves with the desire to control what was more powerful than themselves - hence began the articulation of channelized streams. As Dilip da Cunha puts it, “the river can be worked to make life more comfortable. It can be channeled, dammed, diverted, divided, dispersed, linked and extended to serve a variety of needs and aspirations. It is no doubt why the line of separation, containment and calibration was conceived in the first place.”

The river was no longer what appeared as “natural”, it had become the lifeline for millions of people. They were divided by a politically charged line, giving birth to the volatile hydropolitics in the Indian subcontinent, and its varied repercussions at different scales between and within the nations.

Case Study : Indus River

On Feb 20 2019, India announced the decision to block the flow of water from three tributaries of the Indus river into Pakistan, days after the Pulwama terror attack in which 40 soldiers were killed in Kashmir by a suicide bomber from Pakistan.

Source: NDTV

Water has become a persistent cause of tension between the two neighbouring countries, that mostly arose due to the allocation of the waters of the Indus river basin. A long standing agreement between Pakistan and its riparian neighbour has outlined the use of the water, which came to be known as the Indus Water Treaty. Since India lies upstream of the Indus river basin, it gains the upper hand in political matters.

Water as Control

Over the years, the race to utilize this abundant resource has intensified with pressures to meet the demands of the growing population, with both countries building dams and barrages as multiple points of control along the rivers to extract water for irrigation and hydro-power generation. This practice has been a long standing imperial legacy of control and maneuvering of the fluvial resources.

Shared river basins require cooperation to maintain peace. But within the Indian subcontinent, these water resources are ill-managed, where built infrastructure is imposed on the natural flow of water for diversion and/or containment.

Points of Control along the Indus River Basin. Source: NY Times, Science Friday, BBC World, Foreign Policy, Reuters, News18, The News, Dawn, Times of India, Indian Express

This territorial colonization of streams upstream permanently altered the water flow, capacity and quality downstream. Following the partition of India and West Pakistan, the “rivers were made the spines of the new nations. Their flows were turned more aggressively to improvement not just for security from flood and drought but to catalyze urbanization, industrialization, modernization, commercialization, and other processes by which the race to catch up with the developed world was envisioned.”

Water as Conflict

With the rapid increase in water scarcity exacerbated by the climate crisis, explosive population growth is straining world resources, and hyper-nationalism is testing diplomatic relations, water demand is expected to go up 55% between 2000 and 2050. Water insecurity continues to be an indicator of instability in many regions of South Asia, leading to shortage of drinking water, agriculture and food causing forced displacement and destruction of livelihoods.

Long March in Pakistan Over the Indus River (licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Source: International Rivers

The race to capitalize on this abundant natural resource has resulted in self-inflicted disaster, which has led to unequitable scarcity of water in many areas, and increased instances of flooding and riverbank erosion in others, impacting the daily lives of millions of people and therefore laying the seeds to conflict. This has consequently resulted in political interventions to manage resource allocation and control over the river.

Usually these water bodies help form natural boundaries, and in several cases their access is shared by adjacent entities. The predicament with transboundary water bodies is that the upstream regions can at any moment reduce, stop or pollute the flow of water to the downstream regions. This transforms water reserves into a competitive resource giving way to what is known as “Water Wars’’.

War for water, the next World war?

Source: The Geography of future water challenges, PBL netherlands environmental assessment agency

Water Insecurity

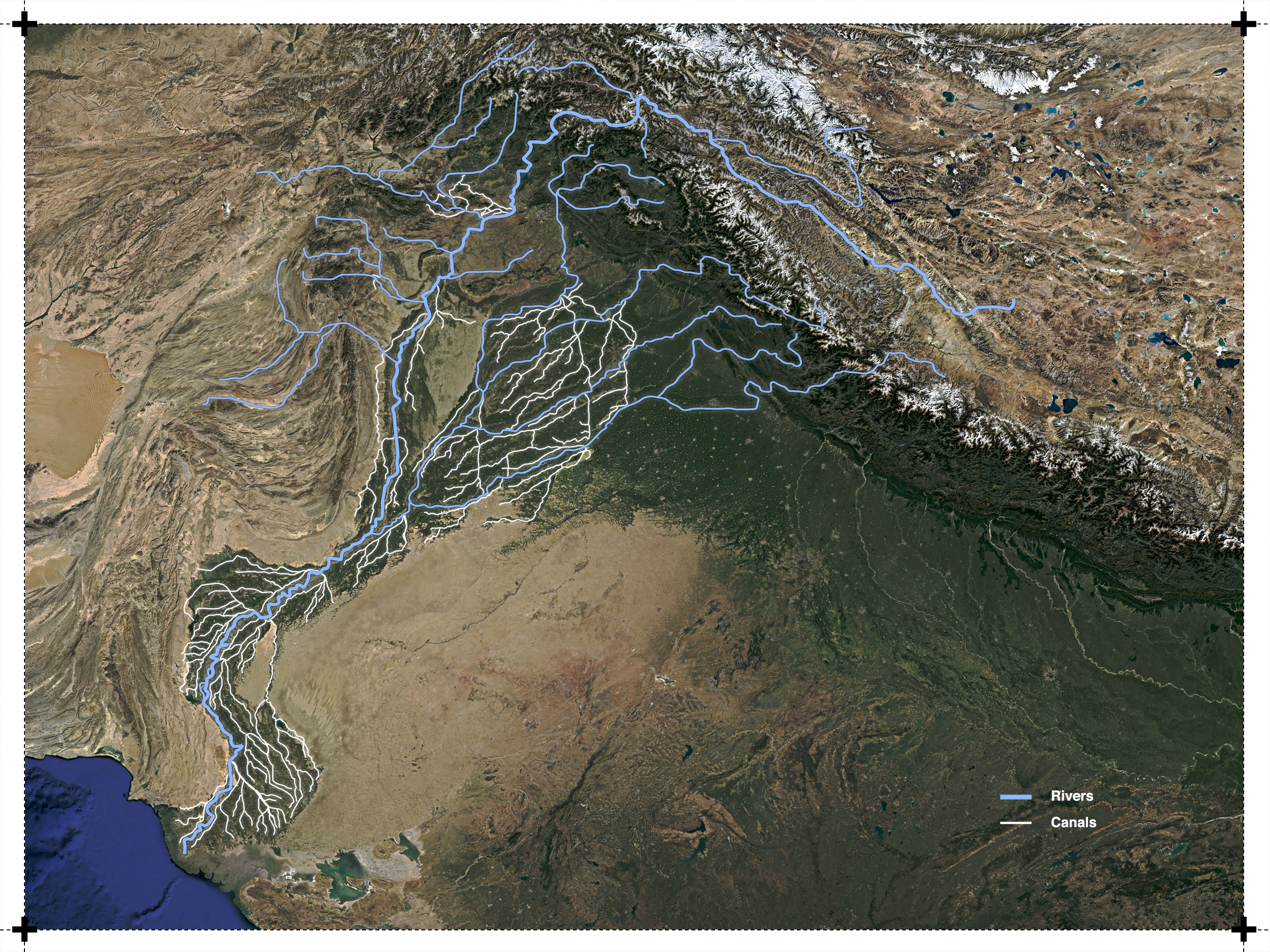

For Pakistan, with its semi-arid climate and erratic rainfall patterns that get increasingly unpredictable every year due to effects of climate change, the availability of water resources is crucial for sustenance. The country is ravaged by frequent droughts, resulting in consequent shortage of drinking water supply for major cities. The Indus river basin forms the only major source of water for most of the country, and hence the need to channel and divert the water, which has been the motivation for construction of dams and barrages along the basin. Today, Pakistan has 3 large dams, 85 small dams, 19 barrages, 12 inter link canals, 45 canals and 0.7 million tube wells to meet its commercial, domestic and irrigation needs. It is these points of control however, that have directly impacted the river causing sedimentation and changes in flow dynamics, which has further resulted in additional problems such as extensive flooding.

People flee from the floods, Sindh, Pakistan (licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Source: Oxfam International

The 2010 monsoon floods affected approximately one-fifth of Pakistan’s total land area. The floods directly affected about 20 million people, mostly by destruction of property, livelihood and infrastructure, with a death toll of close to 2,000.

Source: Democracy Now!

Orchestrating Water

The dependence on the Indus for irrigation dates back to the early civilizations of Mohenjodaro and Harappa. The systems that supply water to the fields were transformed by modern engineering work in the 1850s and further expanded and upgraded under the British occupation of India, into the largest and most complex canal irrigation system in the world. The attribution for most of this comprehensive infrastructure is given to Sir Arthur Cotton, who believed that in order to properly utilize the fluvial resource, it was important “to establish canals for irrigation wherever they were practicable, and to supersede rain and well-water by river water, which carried with it fertilizing matter greatly augmenting its value as compared with all other water.”

Pakistan is an agrarian economy, with over 90% of harvests within the country depending on this extensive canal network, which spans over an area of 36 million acres. Most of the cultivable land hence directly corresponds to the reach of this system. According to Pakistan Economic Survey data, the agriculture sector of the country employs 42% of the entire labour force of the nation, which evidently illustrates the importance of the water from the Indus for the country.

Irrigation canal network in Pakistan

Seasonal Changes along the river

The Indus river system, with its complex braiding channel that is ever in flux, forms a dynamic landscape ecology, that changes drastically over seasons, months and years. On closer inspection while trying to analyse the seasonal changes along the river, we focus on two areas - Kashmor and Firozpur. Kashmor lies closer to the river and therefore is prone to monsoon flooding. Firozpur lies closer to the India-Pakistan border and since India is dependent on rain and river water for irrigation, while Pakistan relies on stored and channelized river water, agricultural patterns differ across the border.

Kashmor and Firozpur landsat imagery showing seasonal variation

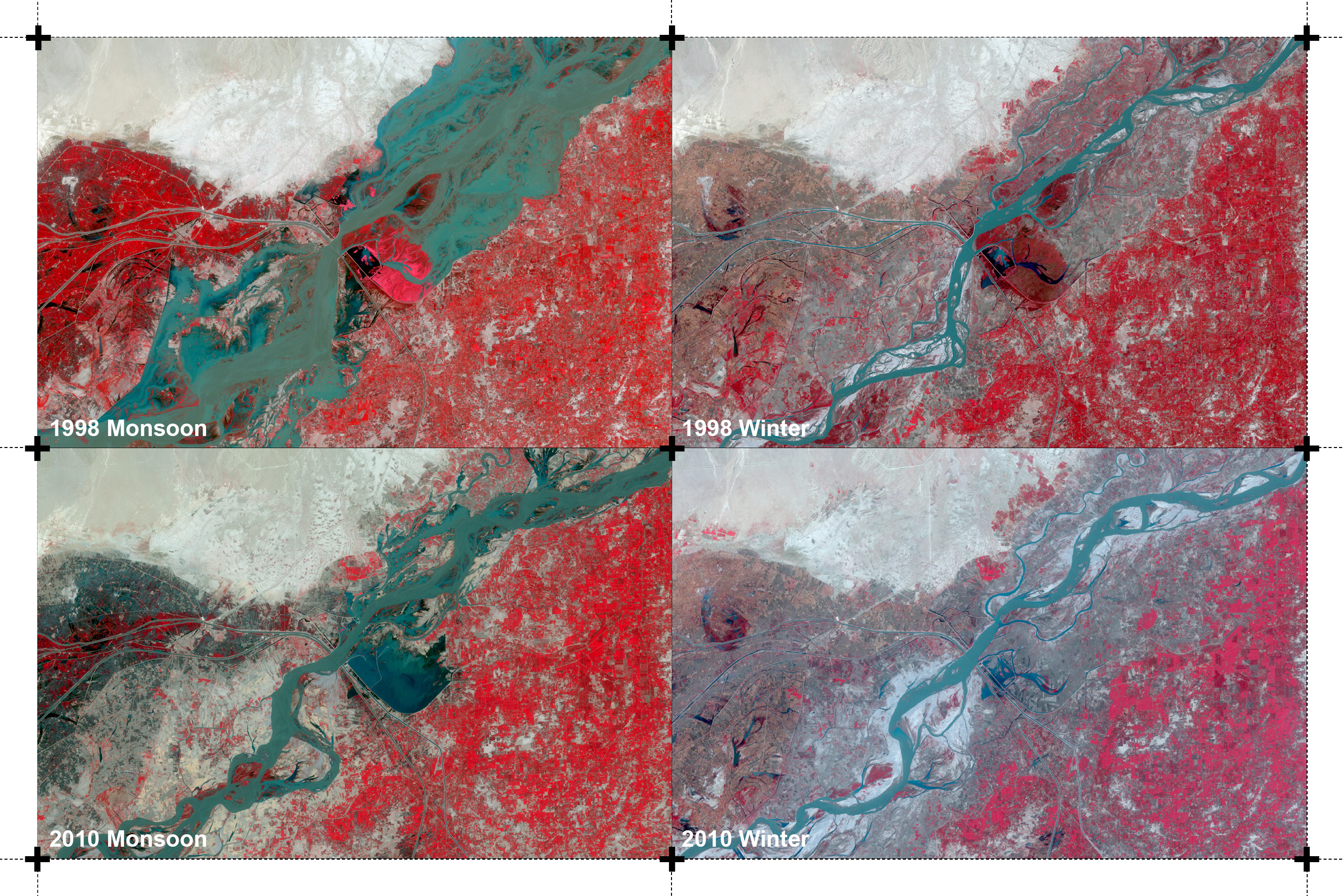

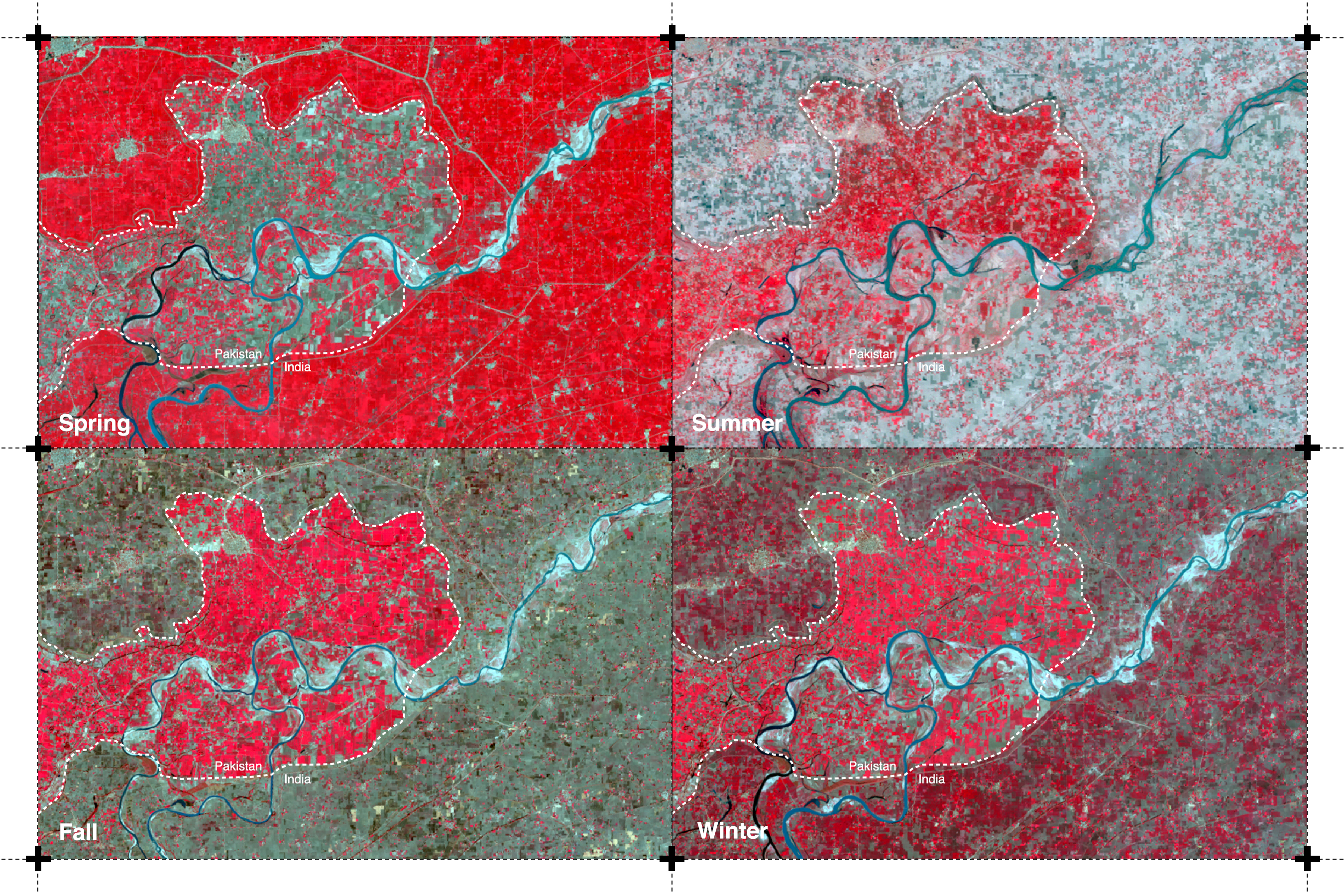

Analysing Landsat imagery to show false colour composites for Kashmor, the agriculture pattern during the Monsoon and Winter seasons is shown in red, The river, its depth and flow pattern are visible in a contrasting blue.

Kashmor false colour landsat imagery showing seasonal variation over a decade

Landsat image classification by supervised classification using spectral signatures from a training sample to represent water flow and agriculture pattern by pixels. It is visible how the monsoon season has affected water flow differently in the year 1998 and 2010

Kashmor image classification showing flow and agriculture variation during monsoon over a decade

During the winter season the direction of river flow has changed due to channeling over the years. The agriculture pattern has shifted based on this change of flow of the river.

Kashmor image classification showing flow and agriculture variation during winter over a decade

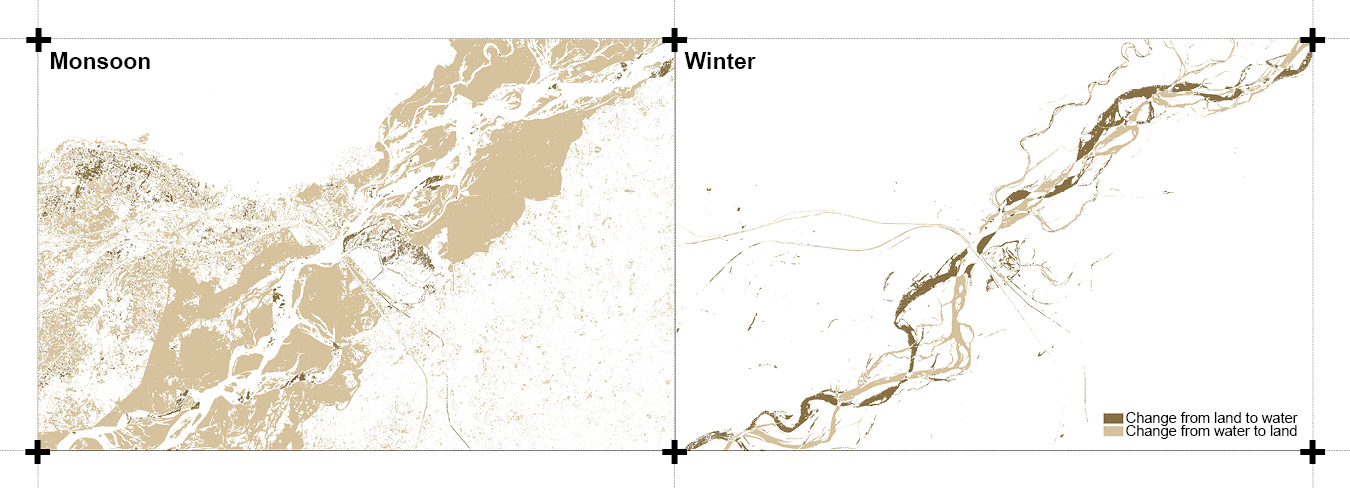

Reclassifying the landsat to perform raster calculation to show how water has changed during monsoon and winter over the years. For monsoon, 70% of the water area converted to land over the decade, while only 1.6% of land converted to water during the same time showing how erratic monsoon flooding changes the water cover area. For winter, around 2.5% of land changed to water and vice versa, indicating that even though net water hasn’t changed, the direction and location of the river has changed which affects agriculture patterns around it.

Kashmor image classification showing change in flow in Monsoon and winter over a decade

Landsat imagery showing false colour for our second focus area, Firozpur, shows agriculture patterns in red and river flow in blue. The pattern contrasts over the seasons showing difference in dependance on rain or river water for agriculture across the border.

Firozpur false colour landsat imagery showing seasonal variation

Case Study: Kaveri River

Kaveri is the third largest river in India, flowing from the state of Karnataka into Tamil Nadu, with the watershed of its seven tributaries extending up to Kerala and Puducherry. The river has numerous sacred associations, in mythology and folklore, that make it a revered entity for the people of South India. It is the source of drinking water supply for major cities in Karnataka, and supports intensive agricultural activity in South India, being one of the most important sources for irrigation of paddy fields in Tamil Nadu. This has resulted in a long-standing dispute between the two states over sharing of the water resource. The Kaveri Water Tribunal was formed to address water shortages in the four states that were facing increased water demands.

Source: NDTV

The Kaveri has been subject to a tradition of diversion and extraction of water for the purpose of irrigation and drinking water consumption, that has carried on since the Grand Anicut dam was built over the flowing water by the Chola dynasty in 100 BC. This practice was intensified during the British rule in India, and came to sustain the needs of the people in South India.

Concrete solutions are yet to be reached over access to this resource, while farmers in Tamil Nadu face droughts and are compelled to commit suicide, and large cities such as Bangalore run dry, as climate change strains the remnants of the once abundant stream.

Rights of the River

“The fluvial frontier is a complex and nuanced territorial condition braiding together multiple elements including conservation, transboundary river management, the geopolitics of resource logistics…”

Rivers have historically been at the center of conflict and instability, and allowing for tools that advocate for equitable access to this valuable resource in practice and policy would be a detrimental first step. In the last few years, rivers have undergone drastic changes with respect to their water quality, volume and flow, catalyzed by climate change, that has consequently left detrimental impacts on riparian ecologies, freshwater systems and expanding human settlements. The situation calls for effective management and allocation of water, and requires flexible frameworks for protection of these water bodies, especially in light increased incidences of flooding and water scarcity.

The relationship between the river and mankind has always been one of reciprocity. The river provides us with water, food and life. Constant attempts to extract more, have left them in a state of disarray. Many environmental movements have advocated for the rights of the rivers, to ensure protection of the inherent right of ecosystems in order to restore their health. Imposition of man-made infrastructures and policies on natural resources such as the rivers continues to affect the landscape and ecologies that survive along the riparian system. The river needs to be celebrated instead of being weaponized for control and conflict.

References

1.Chaudhry, Nadeem. “The 2010 Floods – A case study.”

2.Cunha, Dilip da. The Invention of Rivers: Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

3.Duncan, Ifor, and Stefanos Levidis. “Weaponizing a River.” e-flux architecture, April 11, 2020. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/at-the-border/325751/weaponizing-a-river/

4.Gettleman, Jeffrey. “India Threatens a New Weapon Against Pakistan: Water.” New York Times, February 21, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/21/world/asia/india-pakistan-water-kashmir.html

5.Iqbal, Jaffar. “Irrigation System and issues in Pakistan.” Technology Times, January 9, 2019. https://www.technologytimes.pk/2019/01/09/irrigation-system-issues/

6.Johnson, Keith. “Are India and Pakistan on the Verge of a Water War?” Foreign Policy, February 25, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/25/are-india-and-pakistan-on-the-verge-of-a-water-war-pulwama-kasmir-ravi-indus/

7.Khadka, Navin Singh. “Are India and Pakistan set for water wars?” British Broadcasting Corporation, December 22, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-37521897

8.“Kishanganga dam issue: World Bank asks Pakistan to accept India’s demand of ‘neutral expert’.” Times of India, June 5, 2018. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/kishanganga-dam-world-bank-asks-pakistan-to-accept-indias-demand-of-neutral-expert/articleshow/64466122.cms

9.Mustafa, Waqar. “As rains grow erratic, Pakistan taps irrigation to protect Punjab crops.” Reuters, November 25, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-farming-irrigation/as-rains-grow-erratic-pakistan-taps-irrigation-to-protect-punjab-crops-idUSKBN1DO2OD

10.Nadeem, Mehr, and Sayeed, Saad. “Pakistan accuses India of using water as a weapon in Kashmir dispute.” Reuters, August 19, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/india-kashmir-pakistan-water/pakistan-accuses-india-of-using-water-as-a-weapon-in-kashmir-dispute-idUSL4N25F2I8

11.Nesbit, Jeff. This Is The Way The World Ends. Thomas Dunne Books, 2018.

12.Singapore Red Cross. “Pakistan Floods:The Deluge of Disaster - Facts & Figures.” ReliefWeb, September 15, 2010. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/pakistan-floodsthe-deluge-disaster-facts-figures-15-september-2010

13.Singh, Harjeet. “Water Availability in Pakistan.” Indian Defence Review Vol. 25.4 (October-December 2010)

14.Zaafir, Muhammad Saleh. “Violating IWT India starts Ratle Dam’s construction.” The News, December 15, 2019. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/583790-violating-iwt-india-starts-ratle-dam-s-construction