Fringe Land: Conflict In Formality

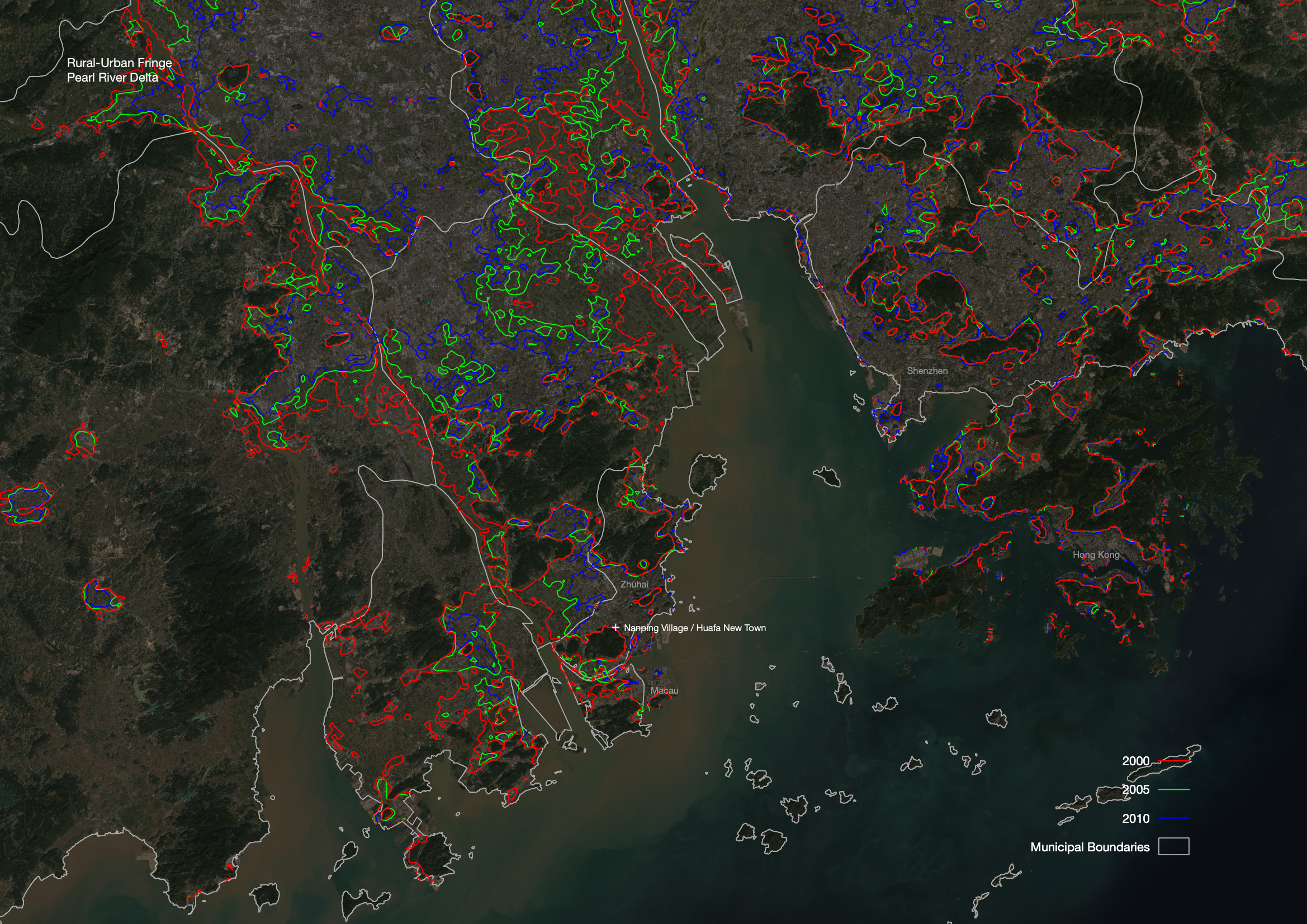

The exploding pixels of China’s urbanized area often translate in a narrative of growth and progress. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

The exploding pixels of China’s urbanized area often translate in a narrative of growth and progress. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

Exploding Pixels, or Changing Contours

Imperious surface area is generally referred to as a primary indicator of the extent of urbanization. The data showed on the map correspond to the impervious surface area in China in 2000, 2005 and 2010, respectively. As the expanding pixels on the map might seem to suggest, the Chinese urban area metastasized drastically in the first decade of our century. Government officials alongside reformist economists and complacent nationalists hurray for a long-waited revival of the middle kingdom, an arrival of what has been well publicized, with extensive transnational media coverage, as the Chinese Century. But what is hidden under the plain sight, under these charts, indices, and maps that seem to tell the story of growth and prosperity? What is rendered invisible, and who is rendered voiceless, in the Chinese deja vu of modernity?

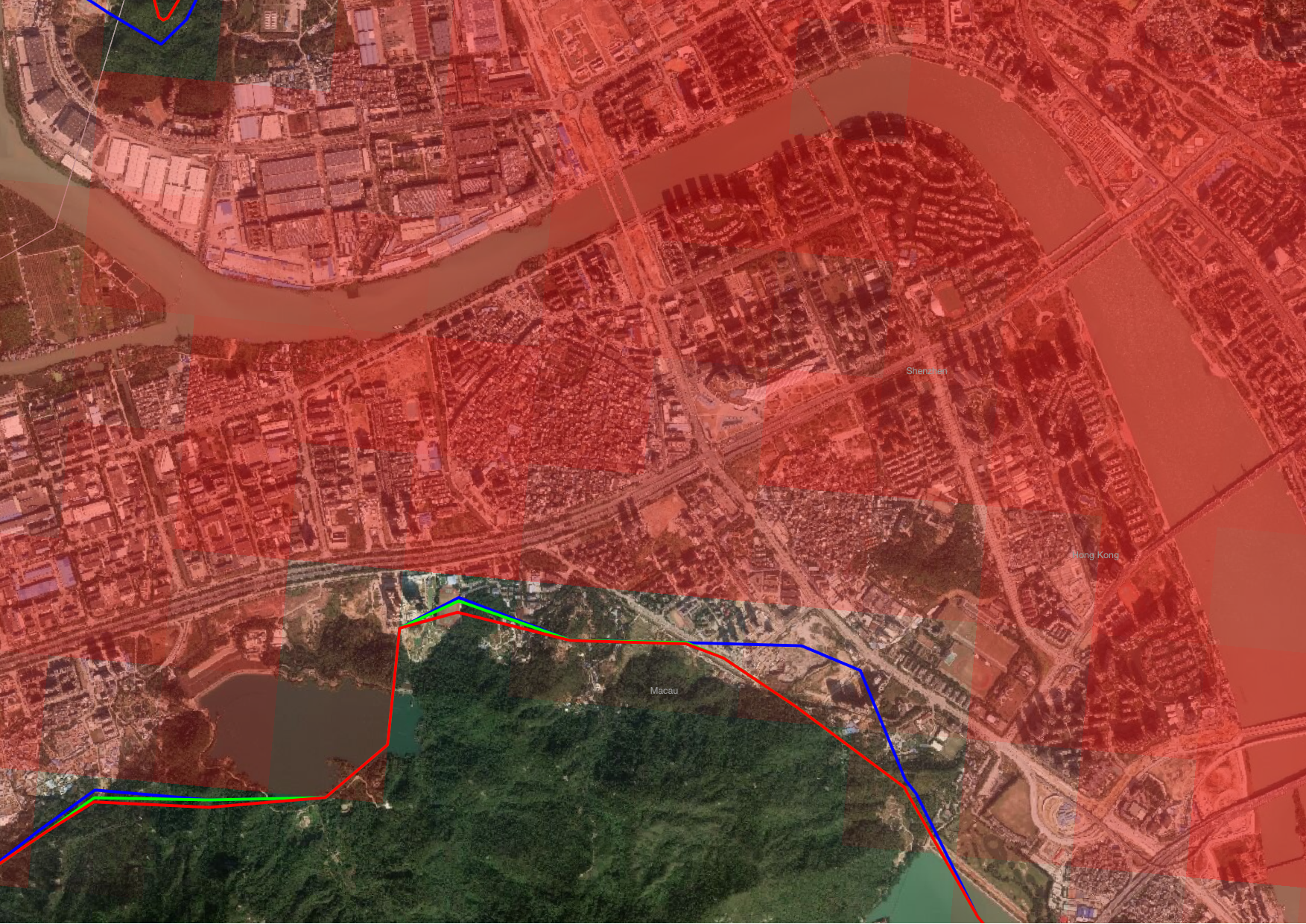

The contours of cities in Pearl River Delta. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

The contours of cities in Pearl River Delta. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

This project resists to draw the connection between the expansion of the pixels to economic progress. Instead, it attempts to appropriate these data acquired, processed and synthesized from remote sensing infrastructure to tell a different story. This project focuses on the changing contour of these pixels as an unsettling political frontier and locates the rural-urban fringe as a space of conflict, deregulation, and displacement.

Nanping Village/Huafa New Town, the case study in this project, is located at the volatile fringe land of Zhuhau, Pearl River Delta. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

Nanping Village/Huafa New Town, the case study in this project, is located at the volatile fringe land of Zhuhau, Pearl River Delta. 2000,2005, 2010. Data Source: Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Ai, B.; Li, X.; Shi, Q. A Normalized Urban Areas Composite Index (NUACI) Based on Combination of DMSP-OLS and MODIS for Mapping Impervious Surface Area. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 17168-17189.

Land Politics with Chinese Characteristics, 1978-2004

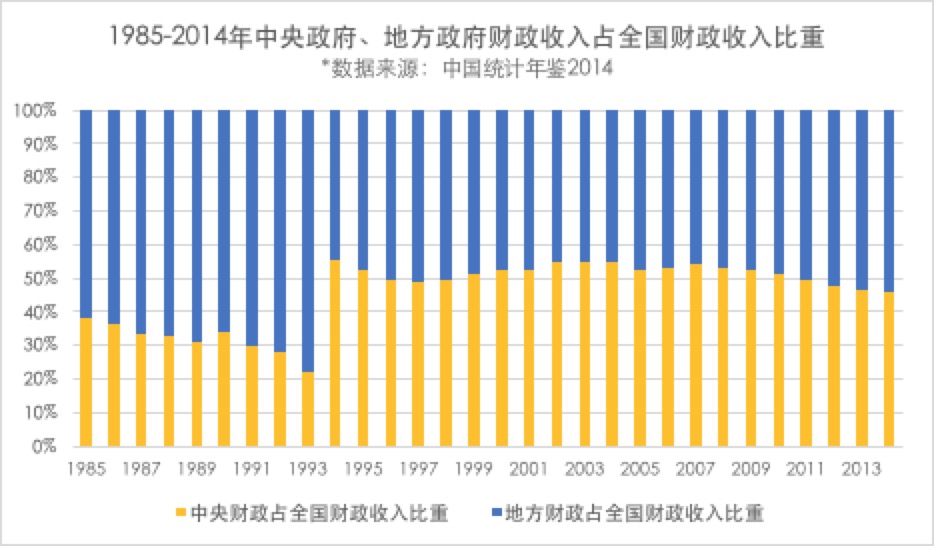

Just like any research that addresses the contemporary China, this one also begins with the Reform and Opening Up policy. Authorized by Deng Xiaoping, this policy was a watershed constitutional turn of PRC that inaugurated what is known as capitalism with Chinese characteristics. The craze for deregulating the economy only escalated after Deng stepping down from the leadership. The 1994 fiscal recentralization reform, put forward by the then prime minister Zhu Rong-ji, assigned most local taxes to the central government. Such fiscal austerity propelled the local and municipal governments to seek other form of income to meet their operational expense. With a loosened-up transference policy, the use right of the land, which is still nominally own by the state, entered the market. Conversion of farmland into industrial Kaifaqu, or development zones that could be later leased out to private developers become the local government’s new source of finance. However, the destitution of rural farmers and the loss of arable land by relentless land grabs in the 1990s have cast into social question three decades of state-led laissez-faire.

The proportion of fiscal revenue of the central government and local governments in the national fiscal revenue from 1985 to 2014. Source: The Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (中国财政部).

The proportion of fiscal revenue of the central government and local governments in the national fiscal revenue from 1985 to 2014. Source: The Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (中国财政部).

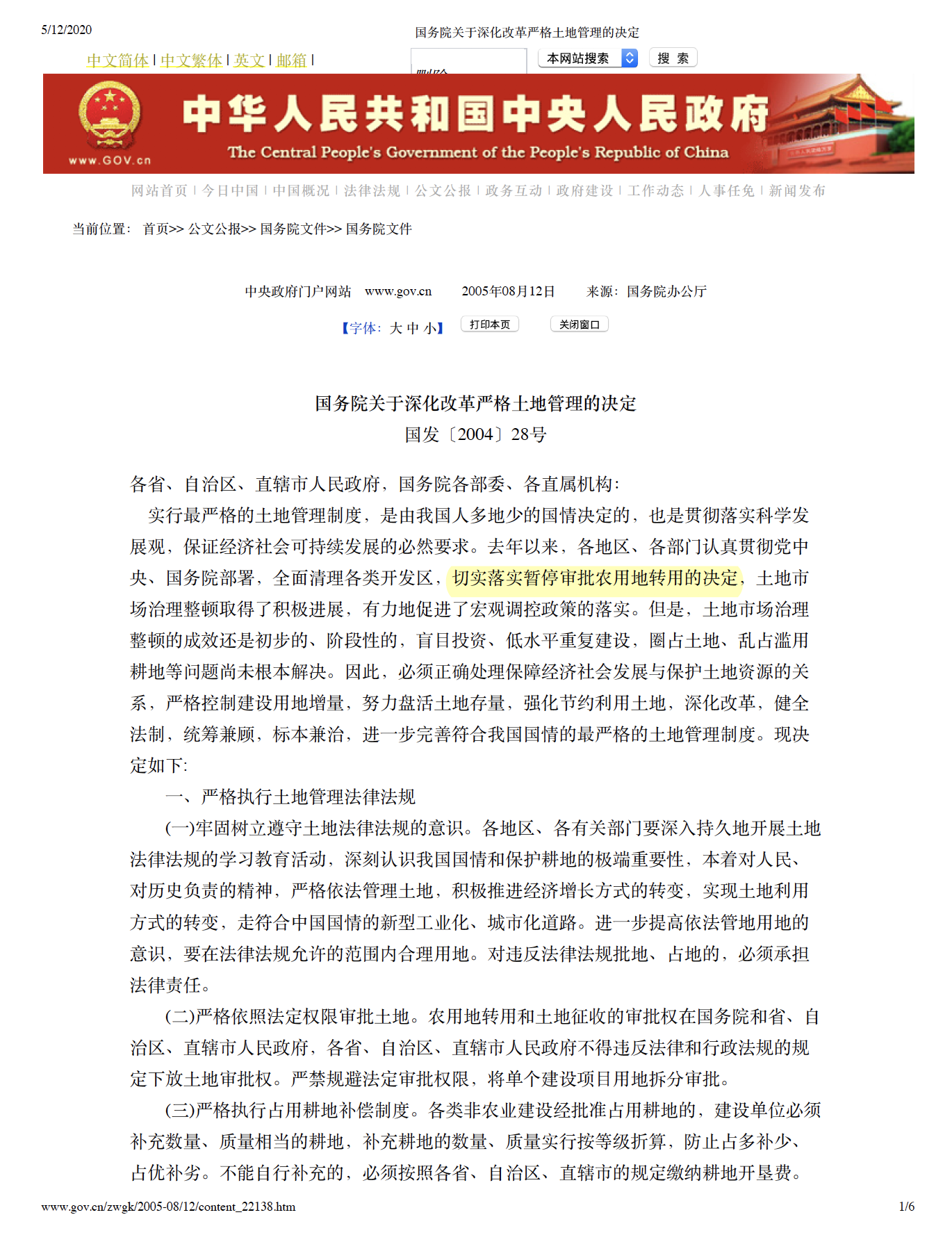

Acknowledging these issues, in 2004, the Minster of Land and Resource tightened control over farmland conversion and reinstalled a more rigorous approval procedure for land development projects. Decades long of unchecked local government collusion and land abuse ended with a new genre of urbanization known as the New Town. It might appear that this was a return to a more regulated economy, as many western neoliberal journalist tend to believed that China is going back to its planned economy yesteryears, but I would argue that deregulation only exacerbated, and in these project the distinction between the state and the developer is no longer clear. (The kind of formality that New Town projects attempt to imply in fact could be understood under this framework a calculated PR work that negotiated the public with the government.)

Highlight reads: “…effectively implement the decision to suspend approval of agricultural land conversion.” 2004. Source: gov.cn

Highlight reads: “…effectively implement the decision to suspend approval of agricultural land conversion.” 2004. Source: gov.cn

New Town, an Entrepreneurial Playground (For You, Me and the Gov)

In New Town projects, the local government usually acquired large reserves of urban hinterland prior to any infrastructural investment or real estate development. In this way, the local and municipal government can profit persistently in a long run by carrying out the New Townsin a multi-phrased process, because an earlier phrase of development would result in a boosted value in its surrounding land. The state thereby could lease the next parcel of land to the second phrase developers for a much higher price. Hence, the value of land is the object of development and the valorization of land was deemed central objective.

The transformation from Nanping Village to Huafa New Town, 1984-2014. Data Source: Google Earth Images.

The transformation from Nanping Village to Huafa New Town, 1984-2014. Data Source: Google Earth Images.

Driven by a blatant entrepreneurial agenda, the state in an ever-deregulated economy is an de facto agent maneuvering in and profiting from the market, rather than a regulator of it. David Harvey has aptly argued elsewhere that the 1970s witnessed a transition in the western cities “from urban managerialism to urban entrepreneurialism.” The shift from the Kaifaqu model (1990s) to the New Town model (2000s), even though historically and geopolitically different from Harvey’s context, characterizes a similar neoliberal transformation in the mode of governance through urbanization.

Rendering of Huafa New Town Phrase 6, 2010. Source: HOK Architects.

Rendering of Huafa New Town Phrase 6, 2010. Source: HOK Architects.

Conflict In Formality

New Town might appear to be more planned, formalized and harmonious in plain sight compared to the previous Kaifaqu model, but the failure of deregulation intensified in these projects. One would only need to look at the urban villages that surround the New Town. Even though these villages seem to perform the “gateways for the arrival community,” – I would argue that they are gateways in so far as the very underpaid workforce they reproduces for the nearby construction sites and the supportive service industry are need - the residences in these villages are strategically kept illegible by the city’s household registration system (Hukou System) through which social security is guaranteed. The strategic invisibility of these informal settlement in urban welfare system renders the residences of these urban villages precarious and insecure. To note that it is the migrant workers who inhabit in the urban village, not the land-owning villagers. By understanding this point one can finally understand Urbanus’ portraiture of the disempowered villagers in the face of globalization is a fictional character. It is then the same story retold again and again, the undocumented migrant workers who live in these villages and work for scanty salary, would later be evicted by the soaring rent caused by the very neighborhood they help develop. Urban renewal project operates precisely at the front of the land valorizing apparatus that displaces and dispossesses the underinsured workers in the deregulated, entrepreneurial age.

Nanping Village, 2010. Source: sina.cn

Nanping Village, 2010. Source: sina.cn

Urban Renewal Scheme for Nanping Village, 2020. Source: Bureau for Urban Renewal in the City of Zhuhai (珠海市香洲区城市更新局).

Urban Renewal Scheme for Nanping Village, 2020. Source: Bureau for Urban Renewal in the City of Zhuhai (珠海市香洲区城市更新局).

Urban Renewal, or the Aesthetics of Deregulation

Recent architectural discourse concerning urbanism in China’s cities seems to be caught up in urban village. Literature on urban village has proliferated since 2010. The corpus of the discourse arguably culminated in the 2017 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture that took place in Shenzhen. Curator-in-Chief Meng Yan, the principle of Urbanus Architects, umbrellaed the shows “Urban/Village: Hybridity and Coexistence.”

Shenzhen/Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture, Poster, 2017. Source: Urbanus Architects.

Shenzhen/Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture, Poster, 2017. Source: Urbanus Architects.

In his curatorial statement, Meng writes, “The spatial and social structures of urban villages are characterized by their inclusiveness and diversity. Compared with many generic cities, streamlined by rapid urbanization and globalization, the living spaces in urban villages are extraordinarily dynamic, showing the indigenous charm of humanity in creating their own homes.” By characterizing the urban villages as “friendly community,” “dynamic,” “flexible,” “diverse,” and even “emblematic of indigenous charm of DIY housing,” his text attempts to argue for the merits of these villages and the cultural necessity for preserving/revitalize them. However, by attending to the historical context, social ramification and political underpinning of urbanization in the reformist China, Urbanus’ biennale and other seemingly progressive architectural gestures that adopts a regional, anti-global stance fit squarely into the neoliberal rhetoric of urban renewal and upgrading. The land valorizing apparatus that structurally displaces and dispossesses the disenfranchised in the urban fringe runs unimpeded, as the existing social hierarchy consolidated by decades of unchecked accumulation in some hands and dispossession in the others remains uncontested in these projects. By romanticizing informality, the agenda of urban renewal and its subsequent architectural and cultural (re-)production emblematize the aesthetics of deregulation.

Rendering, 2007. Source: Urbanus Architects.

Rendering, 2007. Source: Urbanus Architects.

References

-

Abbs, Ackbar. “Cosmopolitan De-Scriptions: Shanghai and Hong Kong.” Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 3, 2000, pp. 769–86, doi:10.1215/08992363-12-3-769.

-

Cheng, Tiejun, and Mark Selden. The Origins and Social Consequences of China ’ s Hukou System. Cambridge University Press on Behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies. no. 139, 2017, pp. 644–68.

-

Franke, Anselm. Territories : Islands, Camps and Other States of Utopia. Berlin: KW, Institute for Contemporary Art, 2003.

-

Fulong Wu. “Post-Reform Urban Conditions.” Urban Development in Post-Reform China : State, Market, and Space, 2015, pp. 1–22.

-

Ngo, Tak Wing, et al. “Scalar Restructuring of the Chinese State: The Subnational Politics of Development Zones.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, vol. 35, no. 1, 2017, pp. 57–75, doi:10.1177/0263774X16661721.

-

Ong, Aihwa. The Chinese Axis : Zoning Technologies and Variegated Sovereignty of Regionalism. 2020, pp. 69–96.

-

Ong, Lynette H. “State-Led Urbanization in China: Skyscrapers, Land Revenue and Concentrated Villages.” China Quarterly, vol. 217, no. 217, 2014, pp. 162–79, doi:10.1017/S0305741014000010.

-

Roy, Ananya. “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory.” Regional Studies, vol. 43, no. 6, 2009, pp. 819–30, doi:10.1080/00343400701809665.

-

–. “Urban Informality.” Readings in Planning Theory, 2015, pp. 524–39, doi:10.1002/9781119084679.ch26.

-

–. “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization.” Planning Theory, vol. 8, no. 1, 2009, pp. 76–87, doi:10.1177/1473095208099299.