The Urban Impacts of Yiddish

Historical Context

Looking West from Norfolk Street along Hester Street (Manhattan) around 1898) Source: http://www.zeno.org

Looking West from Norfolk Street along Hester Street (Manhattan) around 1898) Source: http://www.zeno.org

As an American Jew with Eastern European heritage, little Yiddish phrases are commonplace in my vocabulary, and in that of many people I know Jewish or not. My grandparents grew up speaking Yiddish and would speak it as a code language in front of my dad when he was growing up. It meant that now, like me, he only knows a few phrases here and there. But Yiddish has been able to survive, despite these assimilations and much of that is due to the widespread use of Yiddish by Hasidic Jews. Though these Hasidic Jews would never consider me a Jew myself because of their strict and narrow definition, I became curious as to how our histories are in fact bonded through this language. As Hasidic Jews have unfortunately had to bear the brunt of an increase in Anti-Semitism in the past few years based on their outward appearance of Judaism, I wanted to investigate this one element that ties our common heritage together.

Yiddish is the traditional language of the Ashkenazi Jews (or Jews that originated from Central and Eastern Europe). Although it’s origin is the subject of a lot of scholarly debate, it is largely believed to have originated in the early 2000 C.E. in Central Europe as a Germanic language that was written in Hebrew and also contained some Semitic elements. Yiddish developed into a language with a significant body of literature, prose fiction, poetry, drama, theater, film and press. But the widespread immigration from Eastern Europeans in the early 1900s, the loss of Jewish life during the Holocaust, and the use of Hebrew as vernacular in Israel led to a severe decline in Yiddish speakers. The 21st century narrative maintains that Yiddish has become an endangered language as its native speaking population has decreased so significantly, but there are still a substantial number of speakers (estimates range from half a million to two million speakers) and the language continues to be passed on to the younger generations by Hasidic Jews across the world (Kahn 2016, 643-645).

Yiddish in New York

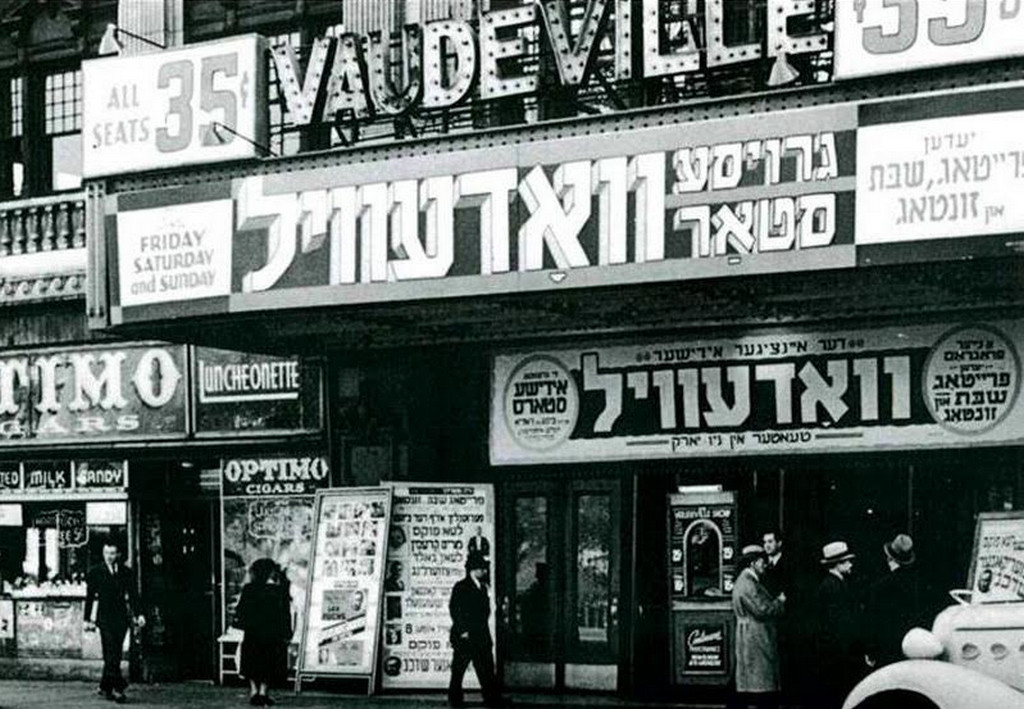

The National Theater on Lower East Side ca. 1912 Source: jewishstudiescolumbia.com/myny

The National Theater on Lower East Side ca. 1912 Source: jewishstudiescolumbia.com/myny

By the early 1900s, over 1 million Jews were living in New York City, with a large percentage of them reporting their first language as Yiddish or Hebrew. This number continued to rise as Jews continued to flock from Eastern Europe to the Lower East Side (McMahon 2017). The area became the hub of Jewish life and with it Yiddish culture. A strip of theaters emerged called the Yiddish Rialto, with upwards of 20 theaters showing Yiddish plays and comedic acts. Along with a rich theater and nightlife culture, also came seven Yiddish language newspapers that had a daily readership of over 500,000 people; the Forward which remains a Jewish publication and whose building still remains on the Lower East Side. At this moment Yiddish had become an important language of public and private discourse in the city. But with that came the absorption of English influences on the language; words like shap (shop) and payde (payday meaning “wages”). It also influenced the syntax of Yiddish. But Yiddish also impacted how Jews spoke English–and still does today (Polland 2012, 209-211).

Source: myny.ctl.columbia.edu

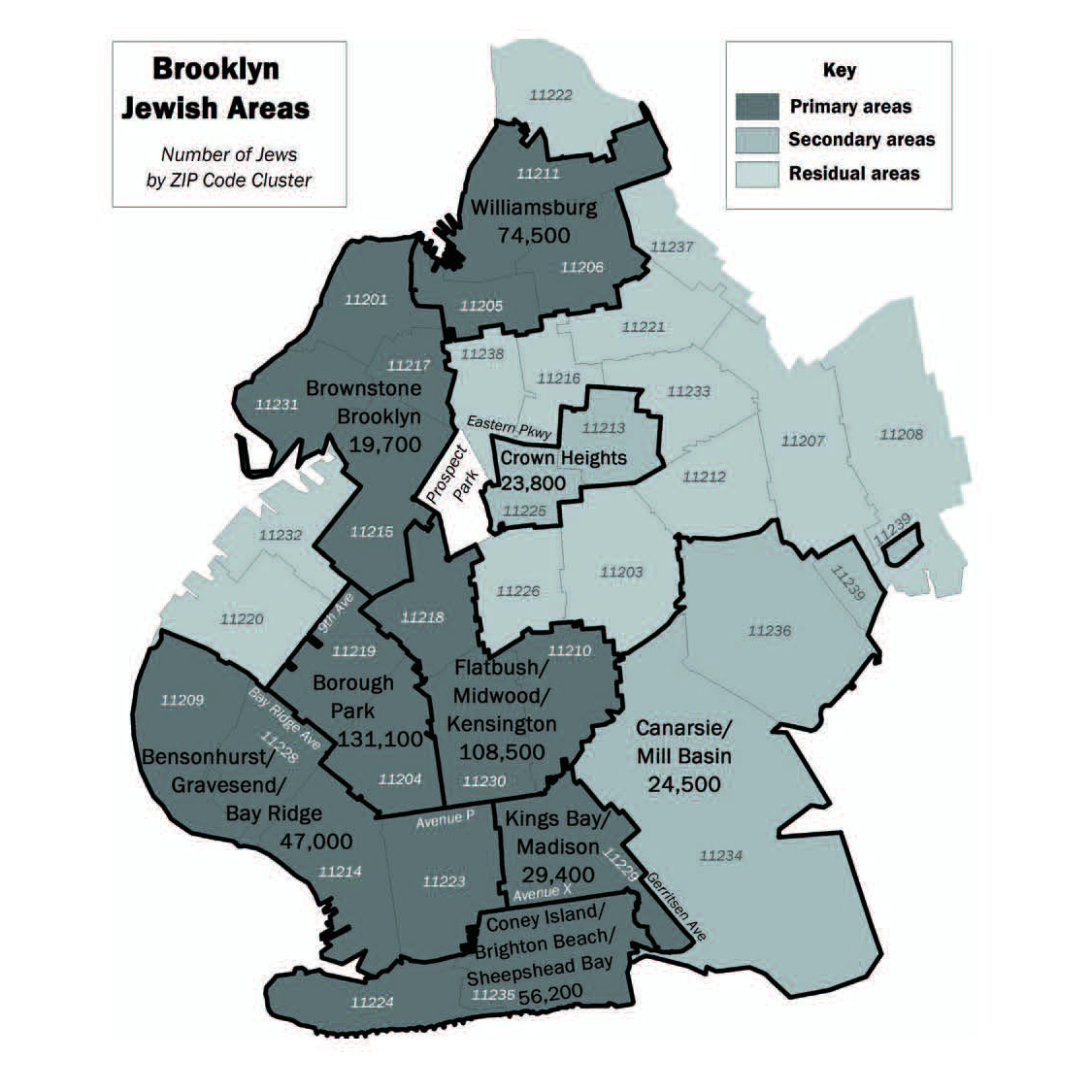

With time the use of Yiddish began to dissipate within the immigrant communities. After World War II there was a desire to assimilate, and with that came a decrease in the generational teaching of the language. But as the number of first and second generation Jews were beginning to assimilate, Hasidic Jews were arriving in New York from Eastern Europe after the Holocaust with a different agenda. With a large portion of the Hasidic community having recently perished, Hasidism was transplanted around the world to America, Israel, Canada, Australia and Western Europe, but today ten of the major Hasidic communities (or dynasties) are headquartered in Brooklyn, New York. It is important to understand that the Hasidic ideal is to live a hallowed and virtuous life. These tight knit communities are spiritually centered around a dynastic leader known as a rebbe. In the wake of the Holocaust, a goal of these communities has also been to preserve a bygone way of life from Eastern Europe and to regrow a large Jewish population. This is why many families are encouraged to have many children. Another of these continued practices from the past is the use of Yiddish. Yiddish was used in the Hasidic communities of Eastern Europe in daily life because Hebrew was seen as the holy language reserved for prayer. As the Hasidic communities grew in Brooklyn, so did the number of Yiddish speakers.

Source: Jewish Community Study of New York: 2011 Geographic Profile | UJA-Federation of New York

Source: Jewish Community Study of New York: 2011 Geographic Profile | UJA-Federation of New York

Yiddish in Borough Park

Photograph by Ann-Renee Rubia Source: eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/reelneighborhoods

Photograph by Ann-Renee Rubia Source: eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/reelneighborhoods

When beginning to understand where these communities have grown in Brooklyn they can be almost immediately identified by the location of Yiddish speakers. Using the mapping of Jill Hubley a few specific Hasidic communities become almost immediately visualized –one being in Williamsburg, and another in Borough Park. To then further define the physical outlines of these communities one can look to the mapping of the Eruv. The Eruv is a boundary used by observant Jews to expand the area where they can carry objects on the Sabbath. It is a continuous piece of wire or string attached to different kinds of fence posts. Maps denoting the outlines of these lines depict a further pixelation that one might understand as the Borough Park Hasidic community.

What then can be deduced about this community that has been able to create a physical and linguistic enclave for themselves in Borough Park based on their lines of “enclosure”? If we understand that Yiddish had become virtually extinct before the exponential growth of the Hasidic community, it may seem instinctively positive that they have been able to preserve the use of Yiddish within their neighborhood. As Romaine Nettle writes “a language can only thrive to the extent that there is a functioning community speaking it, and passing it on from parent to child at home.. A small amount of environmental change can cause a cascade of extinction as dependent species become stressed,” (Nettle 2000, 79). But it can be seen that the use of this code language has also been detrimental to the community as it has allowed the perpetuation of cycles of poverty, limitation of free speech, limited education and generally aided the continuation of a way of life that keeps them separate.

A first layer of how Yiddish has been used to insure a common rhetoric across the community can be seen with the results of the 2016 election. Loudspeakers across the neighborhood preached in Yiddish that Trump was the only candidate that agreed with Hasidic values, and in turn the entire Borough Park community shows “red” on the election map (as does that of Crown Heights and Williamsburg). If your only way of understanding the election is through the messaging of your religious leaders, it is no wonder that members of the community seemed to have voted in line.

Source: YouTube

The use of Yiddish in schools has also been particularly detrimental to the advancement of members of the Hasidic community. Hasidic children go to school separated by gender. Boys attend Yeshiva schools taught in Yiddish. In recent years, community members including Naftuli Moster who formed the organization “Yaffed” have implored Mayor Bill de Blasio to investigate whether these schools are of an adequate nature. Moster found that during his senior year of College at the College of Staten Island, he heard the word “molecule” for the first time, causing him to question whether the education he had received was up to par (Miller 2014). Data for the Borough Park area shows education levels that are comparable with the rest of Brooklyn with 47% of residents having at least a high school degree; in Borough Park this could mean that the education at that level is less than the greater city standards (The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States, n.d.). This is problematic for the boys attending school, but also for the budgets of New York City, as it gives millions of dollars every year to religious schools.

The neighborhood also ranks 9th in the city for poverty levels, and 3rd for rent burden (King 2015, 6). These low income rates may relate to the desire of many Hasidic men seeking to devote their lives to studying Torah and religious texts and not focusing on high paying careers, but it may also be that with Yiddish as your preferred language there are only a small subset of jobs available (most of which within the insular Hasidic community).

In this current crisis, the borders of the Borough Park neighborhood are defined by an even more upsetting statistic of the life lost to Covid-19. The neighborhood has some of the highest number of cases. Much of this is due to the disregard for social distancing, and the prioritization of religious traditions. But it’s possible that messaging about the importance of social distancing, proper hygiene and hand washing behaviors, and stay inside orders are not being promoted by the community in Yiddish, and thus not communicated to many community members.

Conclusions

Based on these various conditions of the way that Yiddish has impacted life for the Hasidic community, it seems that rather than functioning as a tool of a vibrant culture of the Lower East Side in the early 1900s, Yiddish has been used as a weapon to allow the Hasidic community to reinforce their separation from society. It has forced its members to be completely dependent upon the community infrastructure as they know very little else.

Citations

Bloch, Matthew, et al (2018). “An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Presidential Election.” The New York Times, The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/upshot/election-2016-voting-precinct-maps.html#12.78/40.6352/-73.9755.

Kahn, Lily, and Aaron D. Rubin. (2016). Handbook of Jewish Languages. Brill’s Handbooks in Linguistics. Leiden: Brill. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e025xna&AN=1097850&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

King L, Hinterland K, Dragan KL, Driver CR, Harris TG, Gwynn RC, Linos N, Barbot O, Bassett MT (2015). Community Health Profiles 2015, Brooklyn Community District 12: Borough Park; 36(59):1-16.

“Languages of NYC.” Jill Hubley, www.jillhubley.com/project/nyclanguages/#close.

McMahon, John (2017). “Yiddish: New York’s Lost Language.” Listen & Learn USA, www.listenandlearnusa.com/blog/yiddish-new-yorks-lost-language/

Miller, Jennifer (2015). “Yiddish Isn’t Enough.” The New York Times, The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2014/11/23/nyregion/a-yeshiva-graduate-fights-for-secular-studies-in-hasidic-education.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article.

Nettle, D., & Romaine, S. (2000). Chapter 4 - The Ecology of Language. In Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World’s Languages, 78-98.

Polland, Annie, Daniel Soyer, Deborah Dash Moore, and Diana L. Linden. “Jews and New York Culture.” In Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840-1920, 207-43. NYU Press, 2012. Accessed May 10, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfcb4.13.

“School Enrollment in Borough Park, New York, New York (Neighborhood).” The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas, statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/New-York/New-York/Borough-Park/School-Enrollment.

Social Explorer; U.S. Census Bureau; 2018 ACS 1-year and 2014-2018 ACS 5-year.