Extractive Urbanism: Social and Territorial Fragmentation in Mozambibque's Energy Extraction Landscape

Mozambique’s booming extractive industries have spurred the country’s making of modernity in the post civil war era. Through the lens of urbanism - urban development, foreign investments, infrastructure construction, settlements and resettlements, etc. - this project looks at how the extractive boom is building the country’s economy while characterizing it with spatial and socio economic fragmentation across the national territory.

Overview

The conflict this project addresses is extractive urbanism, a model for the development of new cities. Many places rich in natural resources have reaped great benefits by simply exploiting and exporting themselves. Urban construction of these places is aiming to reinforce this low-cost money-making cycle, called extractive urbanism.

Africa’s urban population will almost triple in the coming 35 years, with more than 1.3 billion Africans living in cities by 2050. But the initial driving force of these urban growths is more a desire to find a fiscal reservoir from external capital than a natural increasing demand. And it is in this particular development form of foreign investment orientation that African cities are rising from the ground up. Mozambique is one of the shining stars. The country’s economy has taken off from relying on foreign direct investment, which is now turning into controlling domestic resources and making profits by exporting them abroad.

Nearly 70 percent of capital flows in exports come from the mining and mining supporting industries, logistics, energy-producing, etc. And the spatial byproducts of this economic model is the rising of Mozambique’s new cities. Tete, Palma, Cuamba, Montepuez, Mulevala, Manica, and Chibuto, etc, are all those names that are spatially aligned with the large mining and mining serving companies. But for these companies, only less than 40% of them are owned by Mozambicans.

Moreover, In terms of annual profits, most of the highest value-creating ones do not belong to Mozambicans. For the largest aluminum mining company Mozal in Mozambique, “Initial investment in Mozal amounted to 40% of GDP but only created around 1,500 direct jobs, with nearly one third held by foreigners”, and “it is estimated that from the US$1.2 billion revenue posted per year, only US$200 million enters the Mozambican economy ”. And the ratio of Mozambican people living under the basic poverty line is a stunning 46.1 percent.

City Scale Research | Moatize, Tete Province, Mozambique

Brief Introduction of Coal Mining

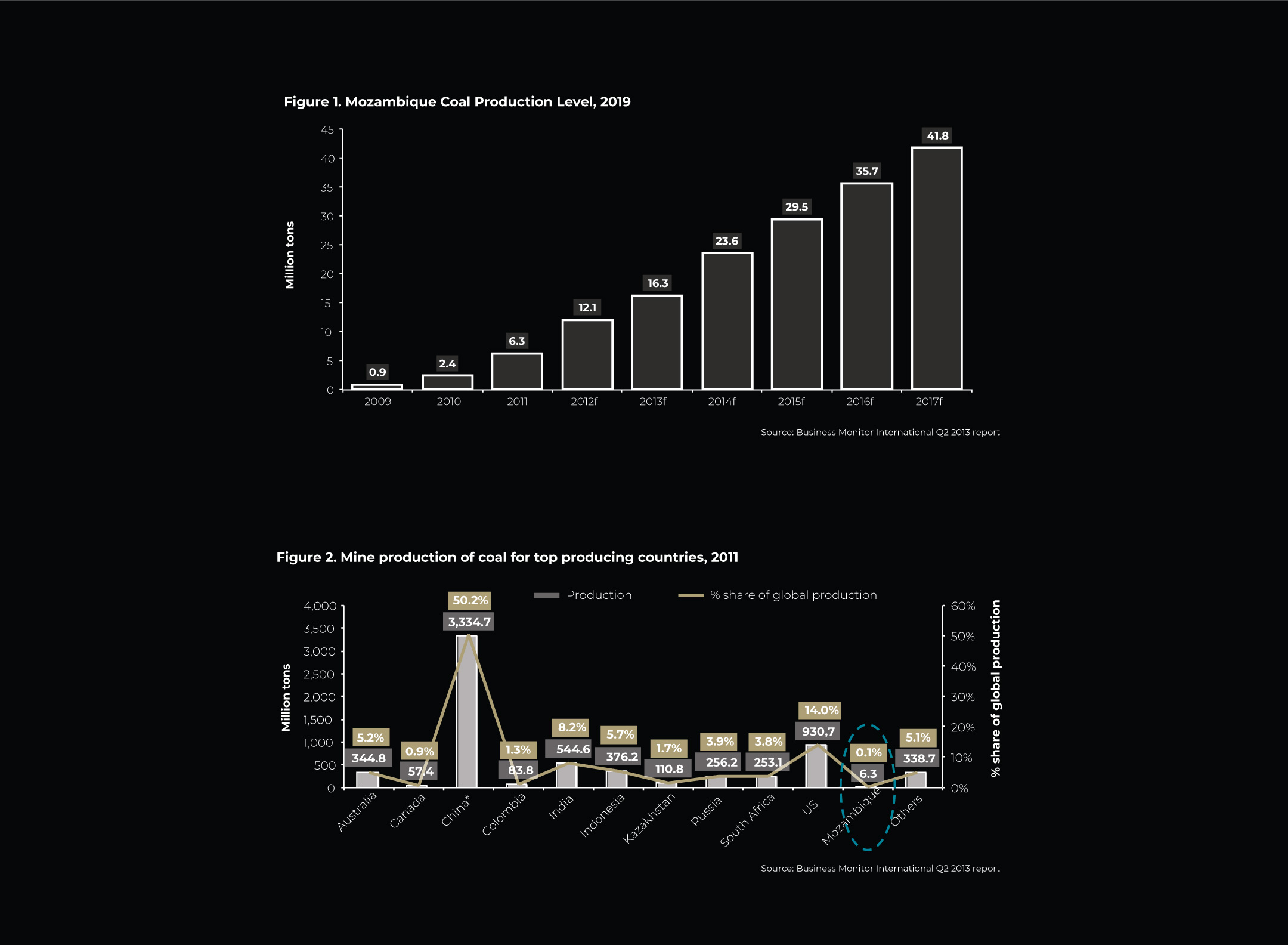

In Mozambique, coal mining is the fastest growing industrial segment. Significant reserves of coking coal have been discovered in the Tete province, which have attracted numbers of prominent foreign mining companies. According to Business Monitor International Report, coal production in Mozambique has been rapidly increasing since 2009. And make Mozambique itself rank among the top 10 largest coal production and export countries in the world.

Foreign Investment in Coal Related Infrastructure

Not only focusing on the development of mines in the country, key infrastructure would also be invested and constructed to facilitate export of mining commodities. There are two developing railroad projects which Brazilian Company Vale Mining has invested— the Sena railroad project and the Nacala corridor. Both are mainly serving for transporting coal or other products for export from the Moatize mine to the seaport like City Beira and Nacala for exports, instead of passenger use.

Land Acquisition Conflicts

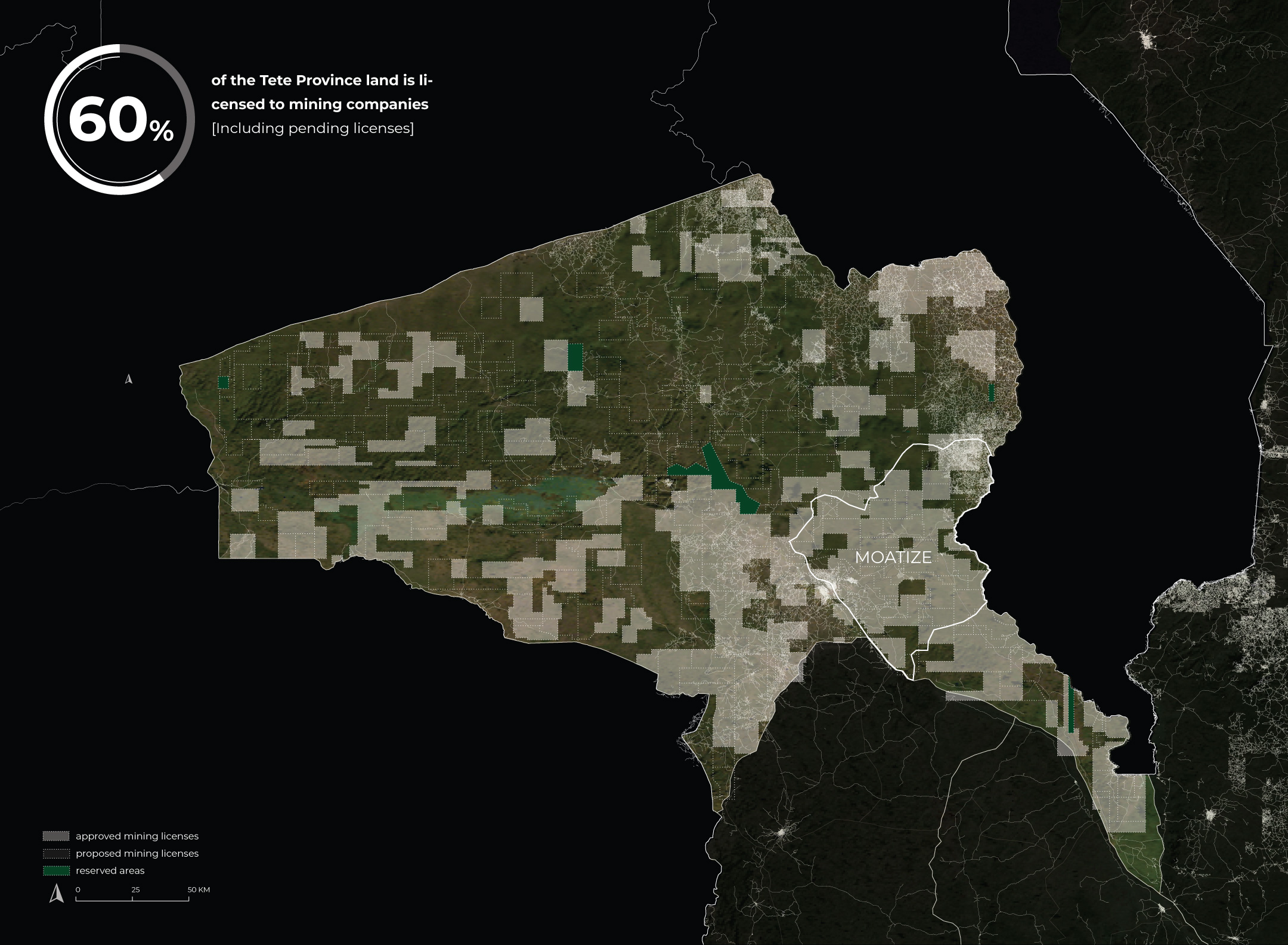

Tete Province, located at northwestern of Mozambique, is a “commodity extraction frontier” rich in coal. It holds an approximately 23 billion tons of mostly untapped coal reserves, with the natural resource boom still in its early stages. Mining concessions and exploration licenses approved by the government cover around thirty-four percent of Tete province land. Including licenses pending approval, around sixty percent of the province’s land are covered. Zooming into Moatize District of Tete, around ninety percent of the district’s land is divided and licensed to FDI.

Resource Access Rights and Resettlements

As two major extraction companies, Vale Mining and Rio Tinto have been producing coal from the Moatize mine since 2009 and planned to have further expansion. Due to the current extraction and expansion, many families have been displaced. Over a thousand families resettled approximately 60 km away from the Moatize coal mining site. The local population of Tete province has suffered from this coal boom led by the foreign companies, since large-scale resettlements have been taking place. As a result, the communities have faced disruptions in accessing food, water, and work. Living conditions have decreased drastically, as many farming households who had “previously been living along a river” and were therefore “self-sufficient”, have now been resettled to sites far away from the markets in Moatize, with agricultural land of “uneven quality and unreliable access to water”. Food insecurity and dependence on food assistance provided by the mining companies has become a serious issue for the families.

City Scale Research | Cabo Delgado Province, Mozambique

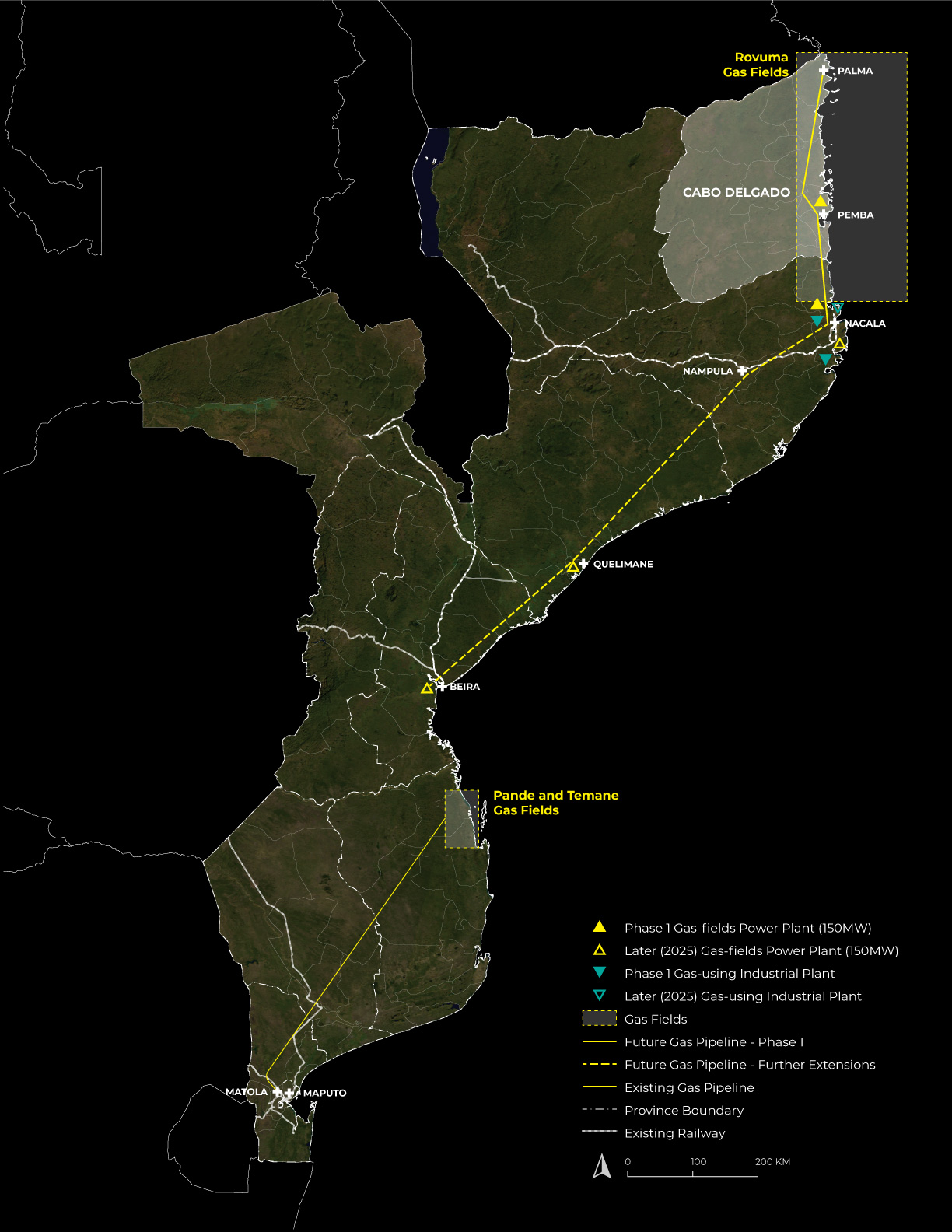

Cabo Delgado | Revuma Gas Fields

In 2010, large reserves of natural gas were discovered in the Rovuma Basin, the offshore area of Cabo Delgado Province, northern Mozambique, which attracted a lot of foreign investment and will make Mozambique the third largest country of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). There are also future plans for pipeline and natural gas plants, yet it remains unknown who will invest in this development. However, the existing pipeline plan in Maputo is going to transport huge natural gas to South Africa.

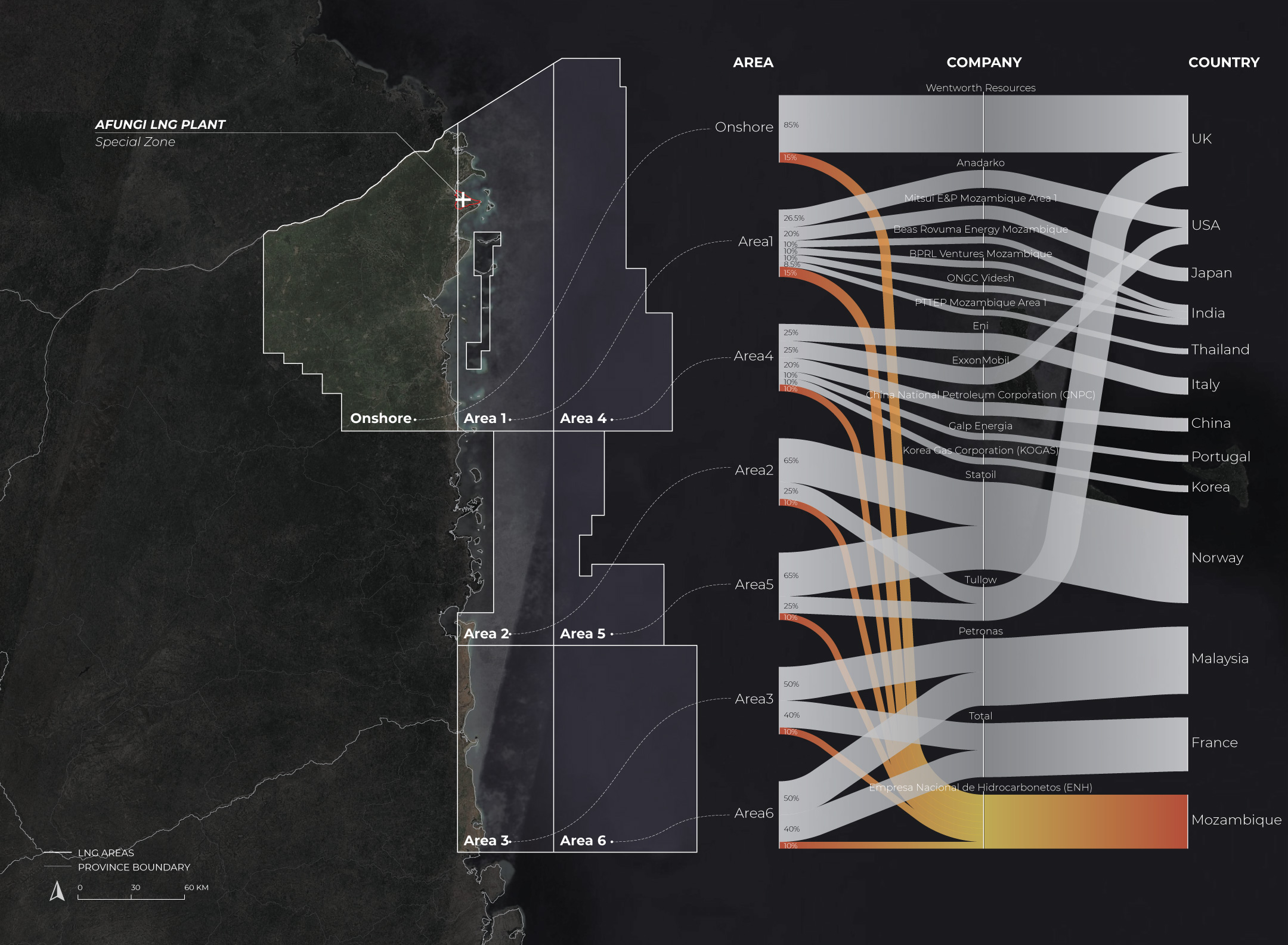

Cabo Delgado | Licensed Gas Areas

The Gas Fields were divided into onshore and offshore 6 areas held by different foreign companies, and a lot of those are owned by foreign governments. In each area, Mozambique holds 10-15 percent shares, but none of the areas is operated by Mozambique. In fact, most of LNG will be shipped to those countries instead of being locally used. To support the LNG production, an onshore facility will be constructed, which is projected to influence over 10,000 People.

Afungi LNG Plant | Resettlement Plan

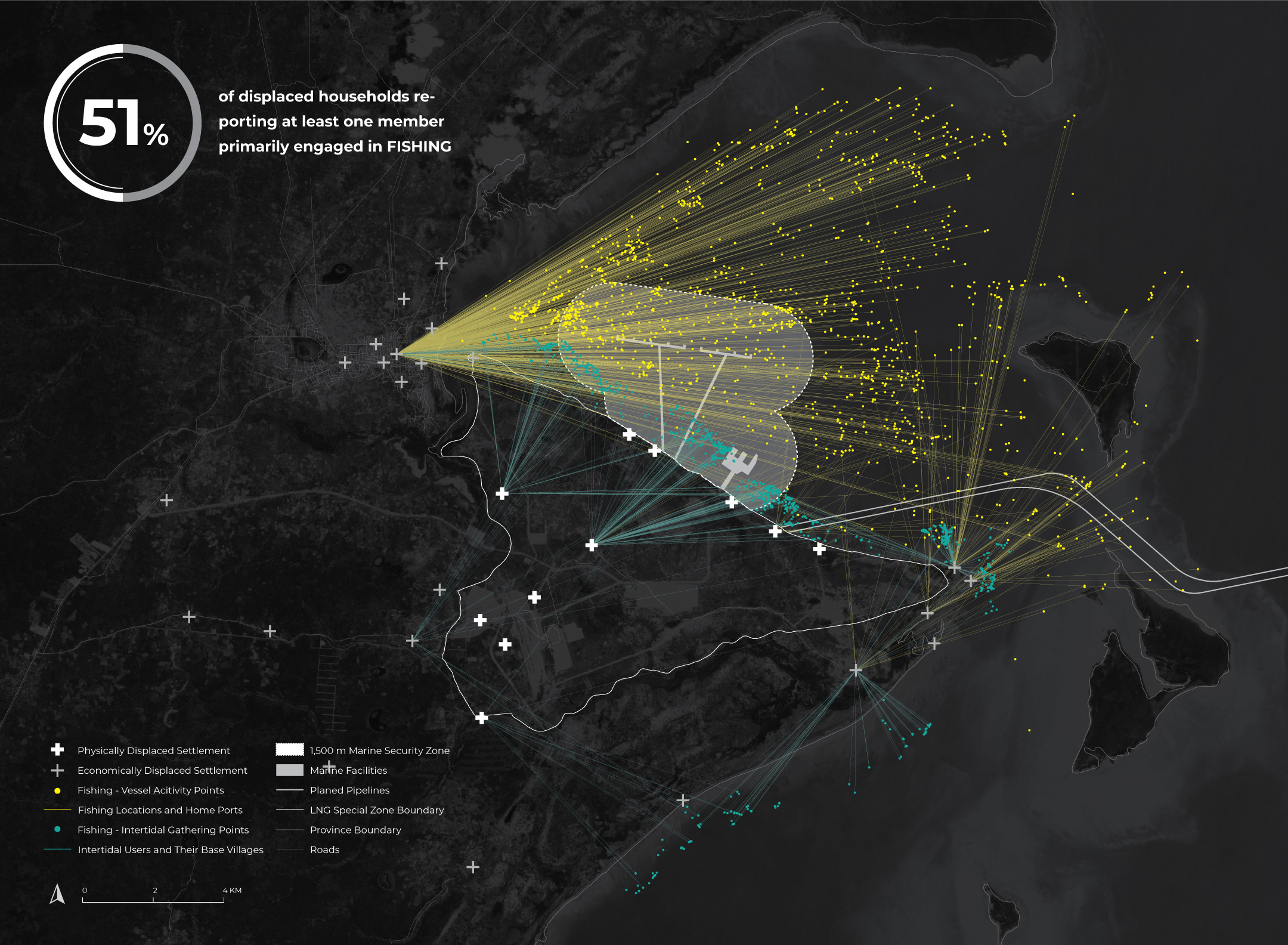

A Resettlement plan was made for the construction of the LNG plant, over 500 households are expected to be physically resettled and another 1000 are expected to lose access to their economic resource. The replacement village is located at the marginal area of the plant, but the replacement agricultural land will be 10-15 km away, and there is a delay in this process while the replacement village is being constructed now.

Afungi LNG Plant | Loss of Main Source of Livelihoods

Among the displaced households, 51% are engaging in fishing, and in coastal villages, the number can be more than 80%. This map shows the vessel fishing and intertidal collecting points as well as the home ports. The restricted marine area will have a huge impact on those fishing grounds.

Afungi LNG Plant | Development in Place

As part of the resettlement plan, the project promised to provide more social services to the local people, However, there are concerns that the construction of the facilities is happening much faster than that of their supporting social services, which can be true through the satellite images.

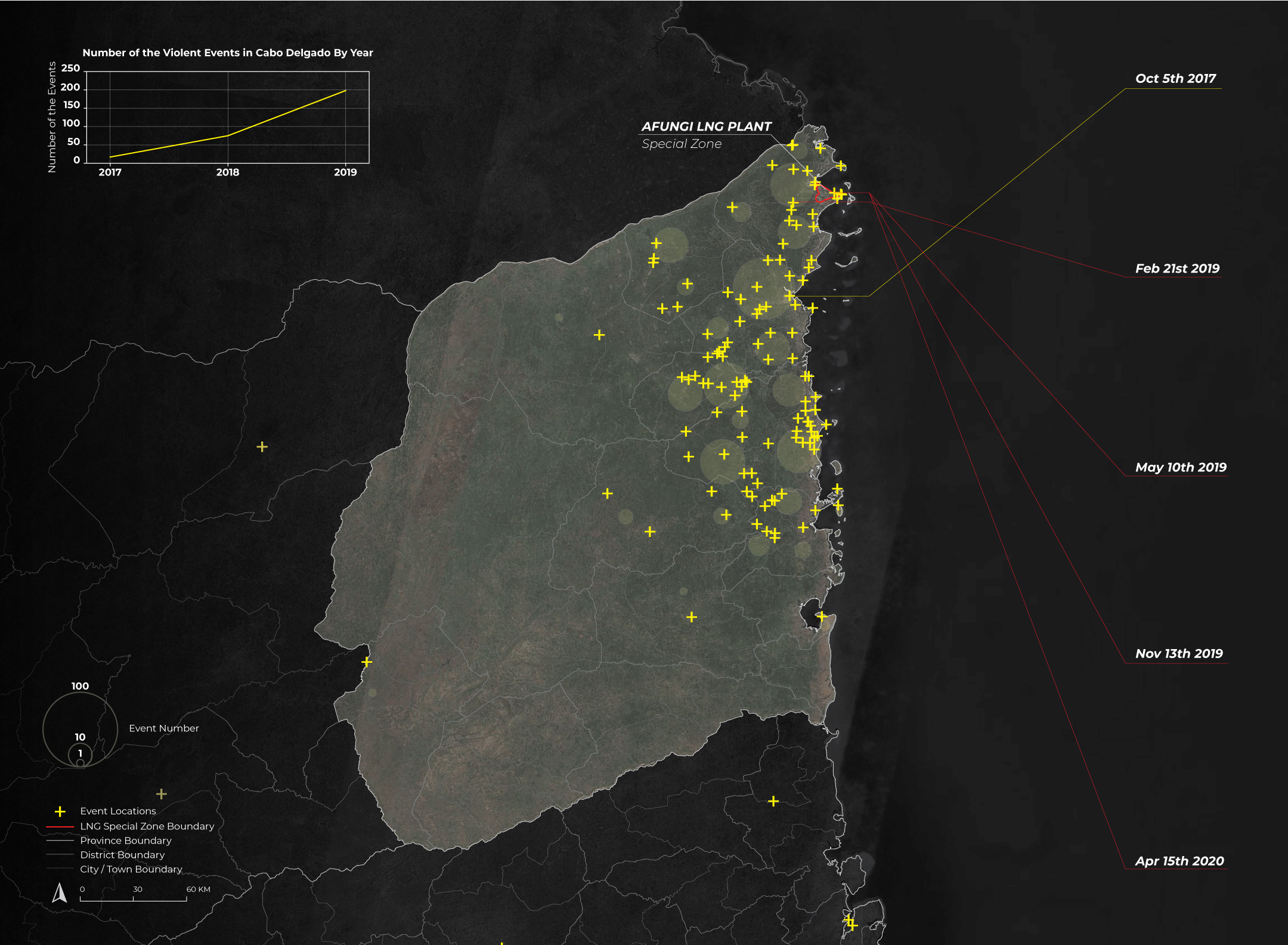

Cabo Delgado | Emerging Insurgency

Apart from the loss of livelihoods, there are also rising security concerns about the emerging attacks since 2017. A series of attacks by Islamist extremists on the civilians have causing dozens people killed. In 2019, they started to target LNG projects. The big companies have been seeking more troops from the government for protection. The ongoing conflict between the insurgents and the military forces have been bringing more pressure to the people who already have a relatively low socio-economic background in the poorest region. People are afraid of going to their fields, and the displaced households with a far allocated field will face potential starvation.

Infrastructure Research | Cahora Bassa Dam

Similar to the extraction industries, large-scale supporting infrastructures in Mozambique are often built by foreign capitals. They are mostly done as a point-to-point model, in favor of lowering the cost of transportation and export of the extracted resources, thus often flying through a great area of territory without any connection to the surroundings.

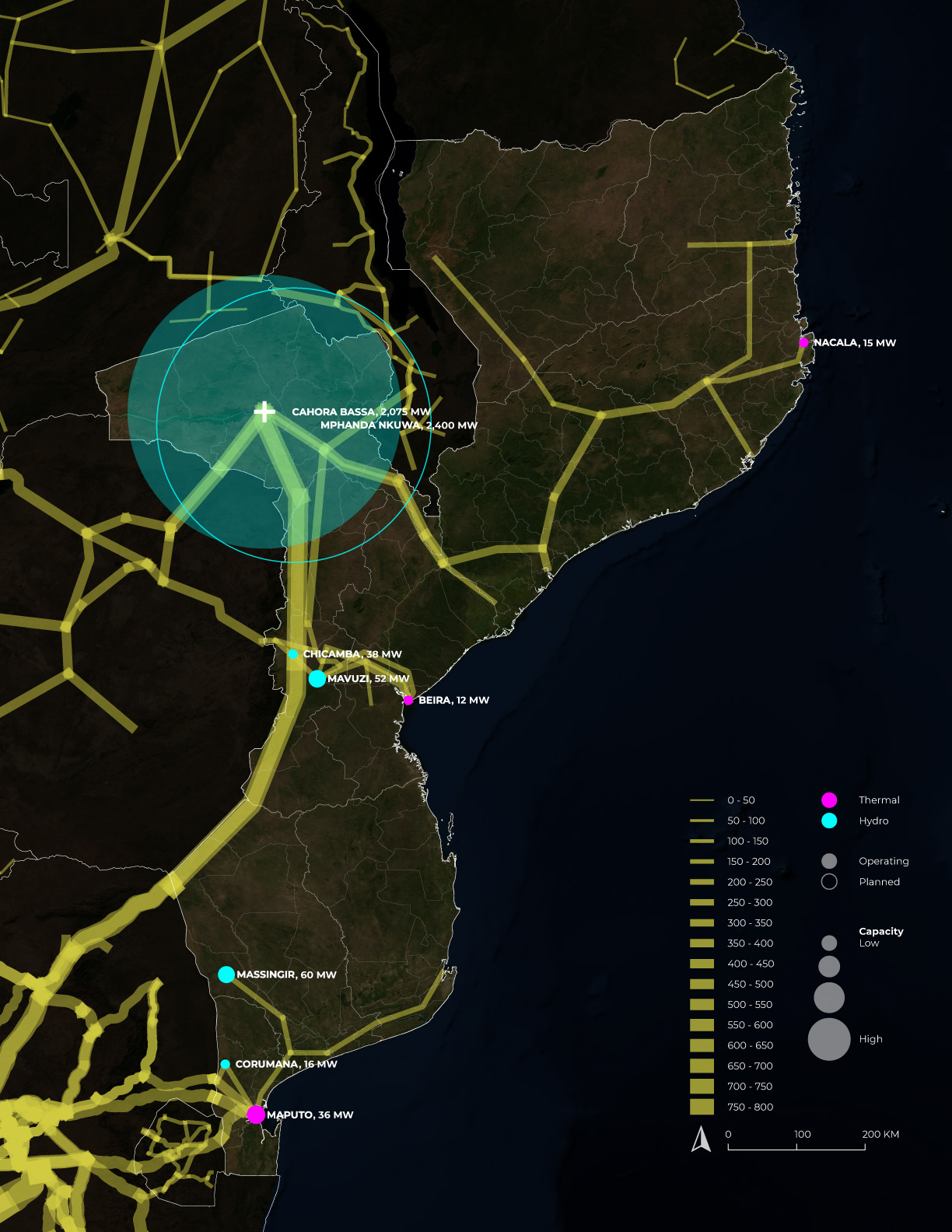

Power Generation and Distribution

The electricity system is one of the examples. In 2014, the country generated 2,626 MW electricity, of which 79% are contributed by the hydropower at Cahora Bassa dam in Tete Province. At 187 gigawatts, Mozambique has the largest power generation potential in Southern Africa from untapped coal, hydro, gas, wind and solar resources. Mozambique is a major exporter of hydropower, coal and natural gas, with the aim of becoming southern Africa’s energy hub.

On the other hand, Mozambique faces substantial challenges in reaching its goal of universal energy access. Its energy access rate is among the lowest of sub-Saharan countries. In a planned future, Mozambique will still sell most of its energy output to South Africa and the Southern African Power Pool, with only a small portion remaining for domestic consumption.

Domestic Power Access

Despite the outsized energy generation, there’s a huge gap between the demand and the distribution. Extraction and export segments are among the top priorities of power supply while the whole system is struggling with the existing highly subsidized tariffs.

There are 4.1 million households with no power access in Mozambique. The current access rate for residence is 29%. This number is 57% in urban areas and 15% in rural areas, yet only 36.5% of the country’s people live in a city.

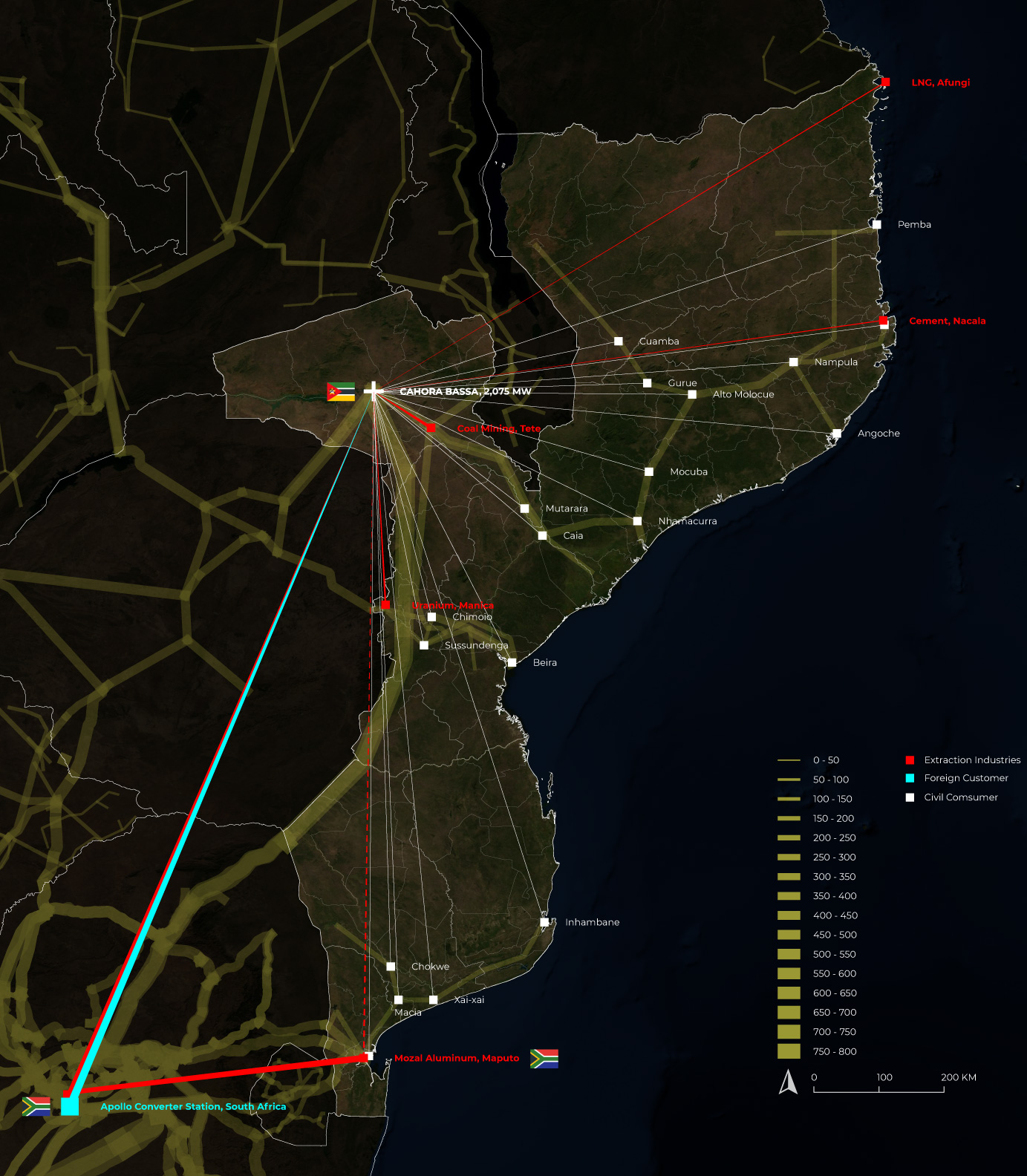

Cahora Bassa | Inbalanced Energy Distribution

At the heart of Mozambique’s energy system is Cahora Bassa, the giant hydroelectric dam on the Zambezi River in Tete province, opened in 1977. As a colonial legacy, this project is financed by foreign investors and the guaranteed sale of electricity to South Africa at below-market prices, in exchange for its support in the colonial war.

In the post civil war era, Cahora Bassa was taken over by the Mozambique government and rendered as a symbol of national identity - ‘o orgulho de Moçambique (the pride of Mozambique)’.

But as a major source of revenue income, annually 70% of the dam’s output has been committed to South Africa’s Eskom utility under a long-term agreement through 2029. A large portion of that is later reimported to Mozambique to serve large extraction industries owned by foreign shareholders. Beyond that, the country plans to expand sales to Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania. This all happens with a majority of the domestic population still having no access to electricity.

References:

- Amanam, Usua, “Natural Gas in East Africa: Domestic and Regional Use”, Stanford University, 2017.

- Kirshner, Joshua, Marcus Power, “Mining and extractive urbanism: Post Development in a Mozambican boomtown”, Geoforum, 61 (2015) 67–78.

- Noorloos, Femke, Marjan Kloosterboer, “Africa’s new cities: The contested future of urbanization” Urban Studies. 55(2018): 1223–1241.

- Perrotton, Florian and Massol, Olivier, “Rate-of-Return Regulation to Unlock Natural Gas Pipeline Deployment: Insights from a Mozambican Project”, USAEE Working Paper, 08(2018), No. 18-353, SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3225143.

- Rawoot, Ilham, “Gas-rich Mozambique may be headed for a disaster”, 2020.

- Santley, David, Robert Schlotterer, Anton Eberhard, “Harnessing African Natural Gas: A New Opportunity for Africa’s Energy Agenda?”, 2014.

- Shannon, Murtah, “Who Controls the City in the Global Urban Era? Mapping the Dimensions of Urban Geopolitics in Beira City, Mozambique”, Land 8(2019): 37.

- CFM- Ports and railways of Mozambique, EP financial statements”, 2012.

- “Final resettlement plan”, Mozambique gas development, 2016.

- “Mozambique power plant”, Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostics (AICO), World Bank Group, 2009.

- “Mozambique: Mining Resettlements Disrupt Food: water, government and mining companies should remedy problems, add protections”, Human Rights Watch, 2013.

- “Oil and gas investments in Palma District, Mozambique: findings from a local context analysis”, Shared Value Foundation and LANDac, 2019.

- “Resources & Energy Statistics Annual”, Bureau of Resources and Energy, Mozambique, 2012.

- “Sub-Saharan Africa - Electricity Transmission Network”, World Bank Group, 2018.

- “‘What a house without food?’, Mozambique’s coal mining boom and resettlement”, Human Rights Watch, 2012.

- Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia university, http://www.ciesin.org/.

- WorldPop, https://www.worldpop.org/.