Weather Patterns, Climate Footprints

Soph Dyer, Sasha Engelmann | Open Weather

Jump to:

Introduction

I. Smoke, storm, dust

II. Open-weather Nowcasts

III. Year of Weather

Tutorial: DIY Ground Station Guide and Automatic Picture Transmission Decoder

Impossible Weather Station at Getxophoto, Spain. July 2022. Image by Getxophoto. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

Introduction

Sasha Engelmann (SE): We are here today to share our project open-weather. Founded in 2020 by myself and Soph, open-weather is a feminist experiment in imaging and imagining the earth and its weather systems using DIY tools. We weave speculative storytelling with low cost hardware and open-source software to investigate and transform our relations to a planet in climate crisis.

To give you a sense of where we are coming from: Soph is an investigative designer, maker of archives, researcher, feminist storyteller, and also my close friend and weather conspirator.

Soph Dyer (SD): This is Sasha. She is a creative geographer, prolific writer, author and diviner of patterns in radio interference. Sasha is also my chosen sister.

Our talk responds to the invitation to be here at the Centre for Spatial Research, Columbia University, as well as this panel’s prompt of “local and historical data” to think through works-in-progress that we have not yet made public.

We want to start and end with the question: How do we read the weather?

We want to explore how our ways of reading weather are informed, not only by meteorology and other sciences, but also by experiential, generational and situated knowledge.

SE: And, secondly, we want to ask: what might it look and feel like to expand and deepen these situated forms of weather-reading in ways that might extend to climate literacies?

To ground these questions in our practice as open-weather, we will begin with a story of a recent workshop and offer one possible reading of the weather on that day.

I. Smoke, storm, dust

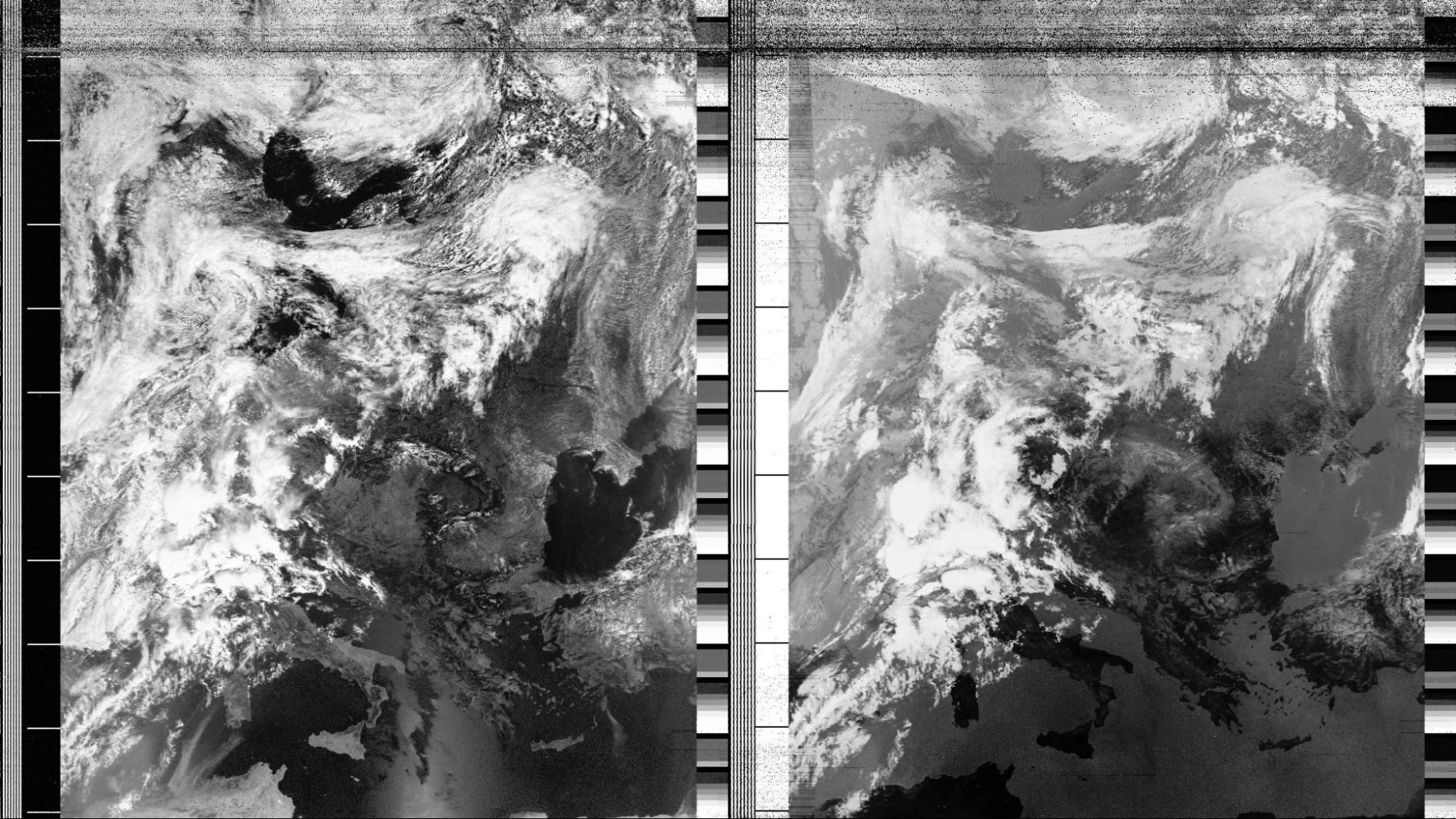

Photo Credit: Open Weather.

SD: It is almost noon on the 24th July, 2023, and the summer school has barely gotten started. Despite being in Austria’s ‘forest region’, the air is hot-dry: what, here, in North America might be called ‘fire weather’.

The summer school’s participants – TU Wien Architecture and Planning students – are gathered outside on a sun-bleached mound. Waving an antenna, I give a lightspeed introduction to the physics of radios and radio waves, before we crowd my laptop to listen for the satellite NOAA-18.

NOAA-18 is classed as a polar orbiting weather satellite. Launched in 2005, its planned mission duration was two years. At the time of the summer school, over 18 years later, it is still transmitting.

Using software defined radio, we are tuned to 137.9125 MHz. At this Very High Frequency the imagery transmitted by NOAA-18 is of relatively low spatial resolution but continuous and near real-time. Its analogue format means that our bodies, the surrounding landscape, and our radio frequency environment will be written into the image as an interference pattern.

At 11:45, an audible tick-tock rises above the radio static. 850 km above Finland's boreal forests, NOAA-18 has entered our line-of-sight. Guided by the satellite’s sound, the students take turns using the antenna to track its movement.

At around 11:55, after passing over our heads, over the Mediterranean basin, and cresting the Southern horizon, NOAA-18 recedes into radio static.

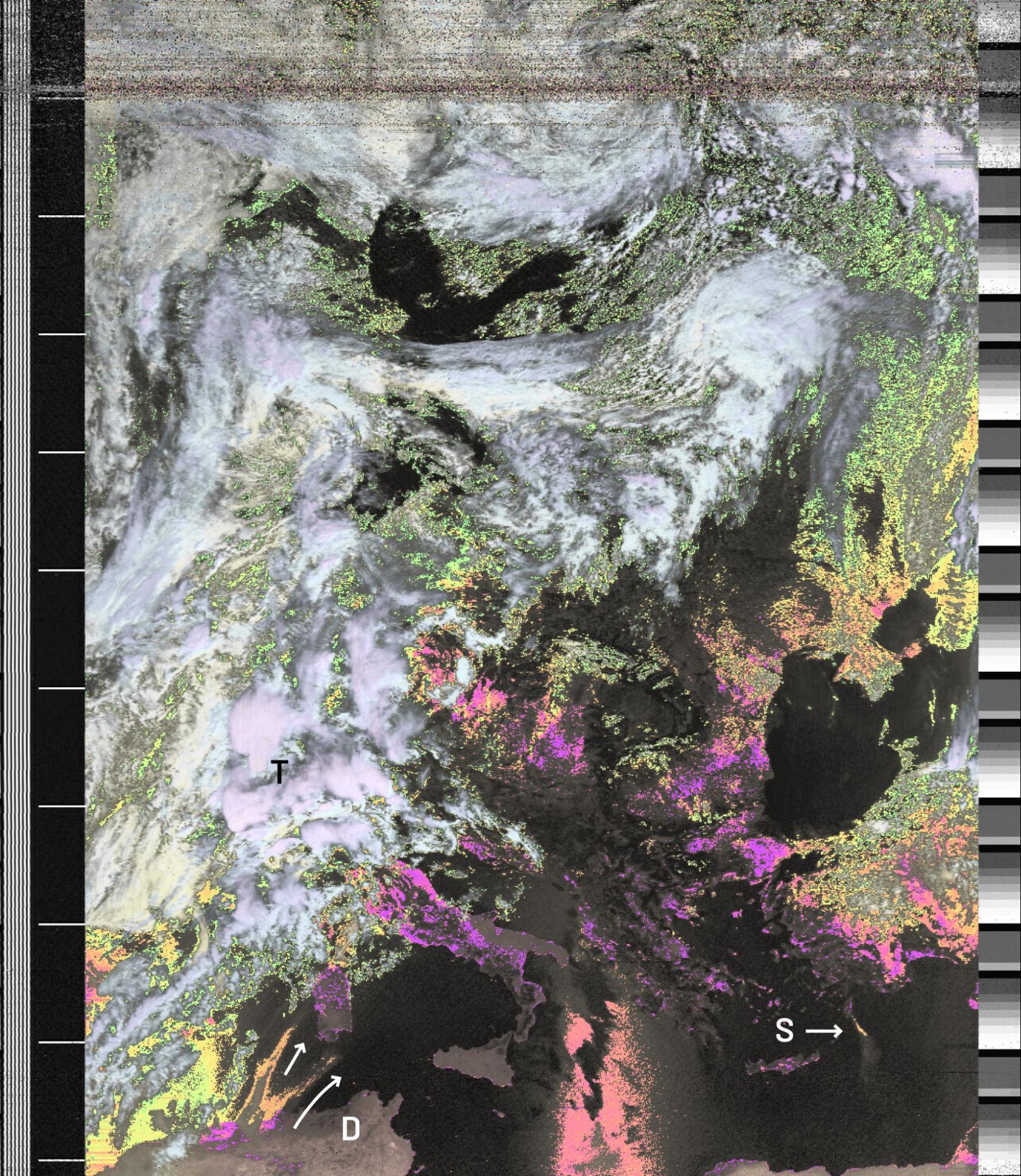

When I image the earth, I imagine another. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

SE: In workshops like this, we learn how to decode the sound into an image. In the interest of time today, we will skip a few steps to return to the question: how do we read this image?

At first, the image transforms our field of vision from the scale of our bodies to that of weather systems, seas, and mountain ranges. It appears to extend, enormously, the scale of our witnessing.

We want to propose, in a ‘para-empirical’ mode after Laura Kurgan (2013), that it offers opportunities for reading the weather, and reading the weather otherwise.

First, in open-weather, reading the weather means engaging with an image that is embodied: a record of a group of people, their movement, environment and glitch prone hardware.

Second, reading the weather in this image means recognising how weather holds time. As philosopher Denise Ferreira da Silva, writes: the very heat in the air that is driving ever stranger weather is the direct manifestation of the racialised and capitalist expropriation of lands, and goods, people and labour over the last few centuries (Ferreira da Silva, 2018).

Third, to read the weather in this image is to close-read not only pixels but also particles: to grasp, within and outside the image frame, unfolding atmospheric events. For Esther Leslie, a satellite image is, “drawn to the dust, the particulate, which it has itself apparently become” (Leslie, 2021: 102).

When I image the earth, I imagine another. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

SD: This image of Europe on the morning of 24 July 2023, is ‘drawn to the dust, the particulate’ in ways that help us to read its multiple, more-than-meteorological weathers.

Southeast of our location, a smoke plume – first mistakable as a peninsula, until you notice its absence in the infrared channel – is visible. The smoke is from wildfires on the Greek Island of Rhodes, which had been burning for a week.

Also recognisable to the students, perhaps because of its local media coverage, are the white, cold tops of towering cumulonimbus clouds obscuring the borders of France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy.

Later on this day, giant hail would fall over Northern Italy, breaking regional records for the largest hail stone for the second time in a week.

It took an even closer reading of the image, a month later, to see – and then be unable to unsee – two fingers of Saharan dust reaching from Algeria into the Mediterranean sea.

In news media, ‘Saharan dust’ is often called a ‘foreign’ ‘intrusion’ or ‘invasion’ into Europe (Sabin and Cantos, 2023).

We need to, “unsettle the idea of the dust as a foreign entity” writes scholar and artist Nerea Calvillo as she argues for greater attention to the specificity of air, “how it interacts with humans and other-than-humans, and what it does in the world, materially, geographically, socially, symbolically” (2023: 62).

In a forthcoming article on ‘Wind’s animacies’, Sasha (writing for open-weather) argues that we also need to ask how dust becomes ‘animated’ as an ‘invader’ or ‘foreigner’ in the first place. In other words, how dust comes to ‘slip’ and ‘leak’ across animacy borders and attains the qualities of, “a lifely thing: lifely, perhaps, beyond its proper bounds” (Chen 2012: 227).

Storm, smoke, dust are three weathers that orient us differently.

Through the embodied and noisy DIY process of receiving and reading this image, we are locating ourselves: our heat, our movement.

Open Work, Second Body. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

II. Open-weather Nowcasts

SE: We have been on a journey to reach the questions we are asking today.

Open-weather emerged five years ago from our combined effort to learn how to capture and decode NOAA satellite transmissions and so images.

We read blog posts, deep-dived into member-only online forums and watched tutorial videos so as to understand how to combine off-the-shelf DIY equipment, free and open-source software.

Our first performance – Open Work, Second Body – was a livestream of us during the first lockdown, reaching from our balconies in London to capture and decode an image from the satellite, NOAA-18.

We co-wrote our own DIY Satellite Ground Station guide aimed at people with no background in radio, and published it on the community science platform Public Lab. In the first months after it was published, several people used the guide to set up their own ground stations in places like Buenos Aires, Seattle and Mumbai.

We also started to lead DIY satellite ground station workshops in which we work with groups to learn how to capture satellite images using amateur radio tools, and to think critically about radio and earth images from feminist perspectives.

DIY Satellite Ground Station Workshop × Sonic Acts. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

In the responses to our how-to guides and workshops we could see a growing network of DIY satellite ground stations forming around the world.

We speculated: does this network really exist? Could we activate this network to capture an amateur and collective image of the earth?

6 September 2020

SD: In 2020, we posed this question by inviting everyone we knew who had replicated our guide, attended a workshop or been in touch with us – around thirty at the time – to receive a satellite image and to submit the audio file alongside notes on the weather.

The response – an incomplete yet planetary “nowcast” of the weather on one day – evidenced the existence of a network, albeit fragile and uneven.

For the purposes of this talk, we want to focus on our second attempt at activating the emerging open-weather network, this time with a specific set of questions around sensing weather and climate.

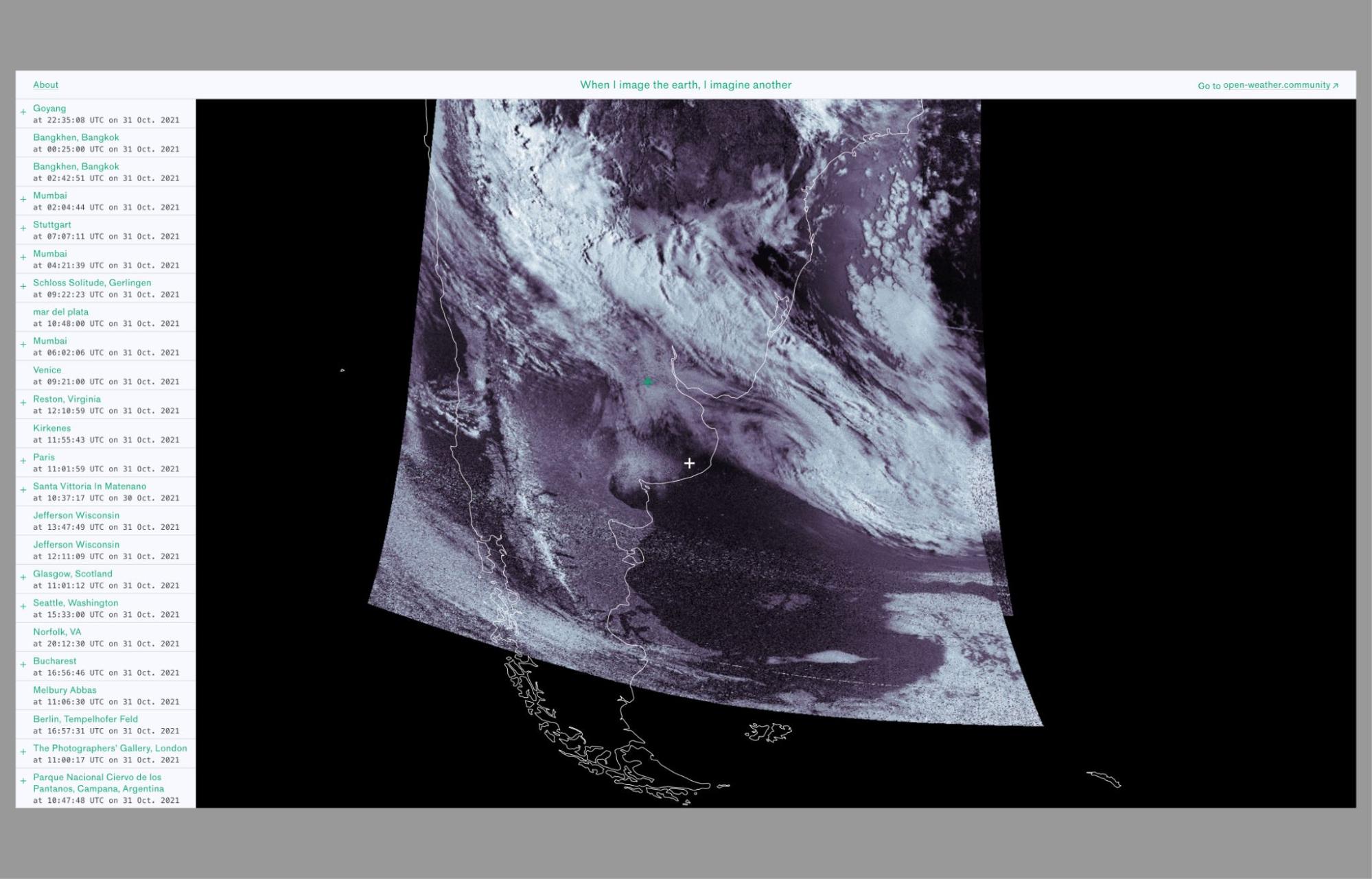

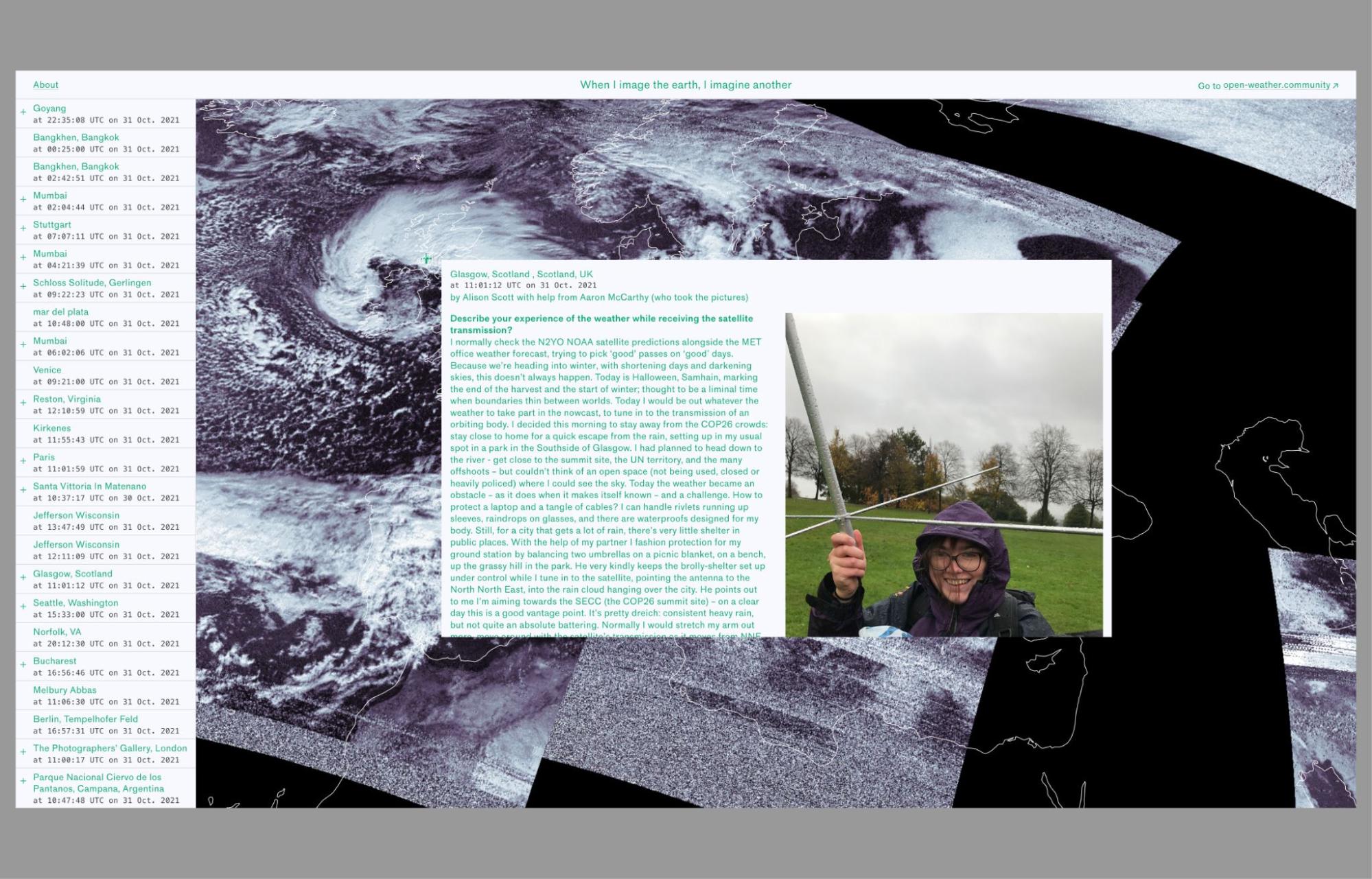

COP26 Nowcast: When I Image the Earth, I Imagine Another

SE: In October 2021, we once again invited the entire open-weather network – numbering around 50 DIY satellite ground station operators – to capture a satellite image on the first day of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

We asked participants to respond to two questions about their experience of the weather on the ground, and how, if at all, they located the climate crisis in their community or environment.

Over the course of October 31st – the first day of COP – 40 images from 29 ground stations were submitted to the open-weather archive, from London to Japan, to Kinshasa in the Congo and Newcastle in Australia.

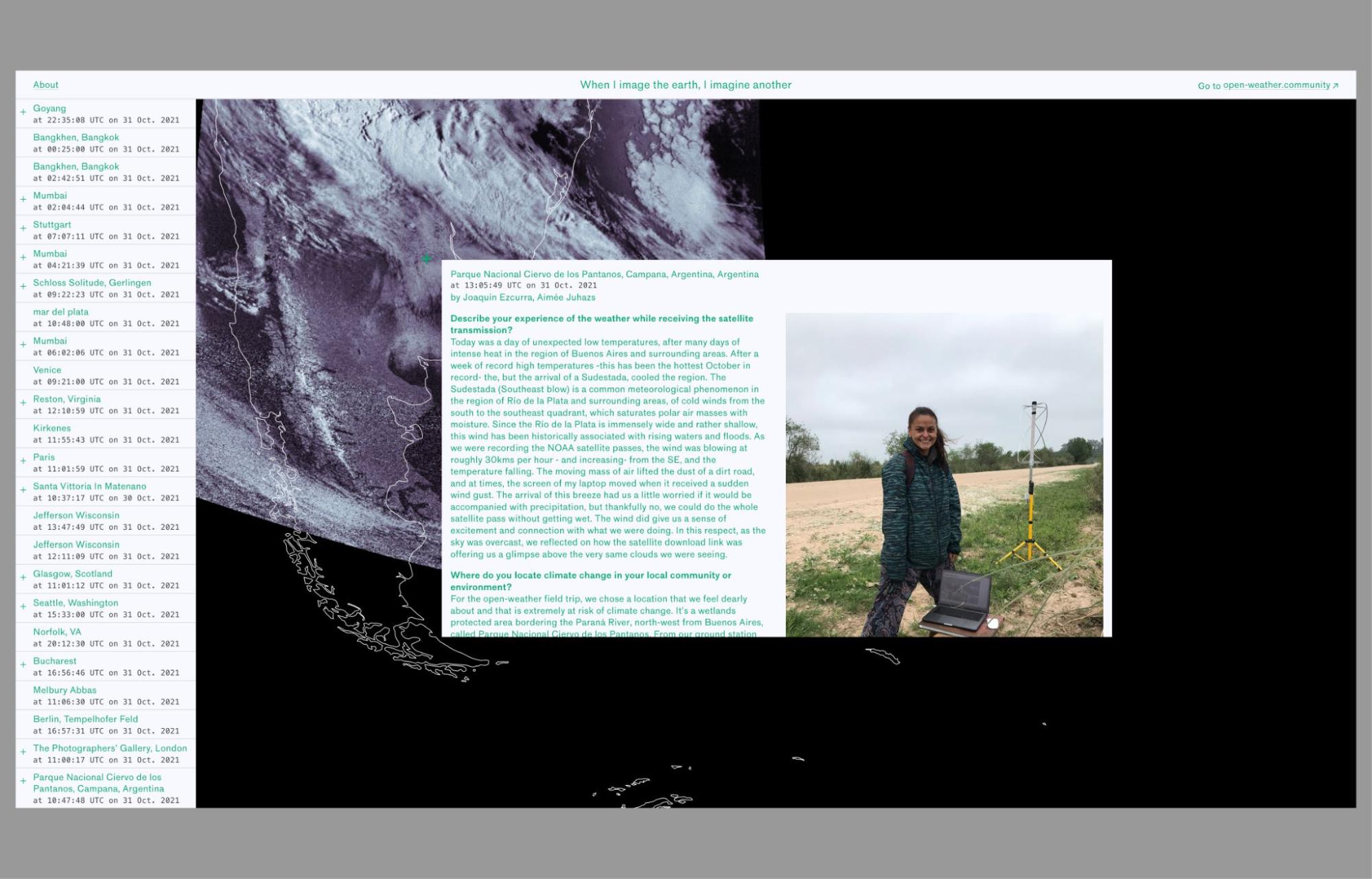

The South American Andes as imaged by Joaquín Ezcurra and Aimée Juhazs in Parque Nacional Ciervo de los Pantanos, and Pablo Cattaneo, also in Argentina. Composite image: open-weather. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

With our long-time collaborators, Lizzie Malcom and Dan Powers who are the studio Rectangle, we batch decoded, processed and georeferenced the individual ‘snapshots’. We then mapped them onto an Equal Earth projection.

The resulting nowcast is a jagged array of images and field notes, interspersed within empty spaces where no member of the network was present.

One way to describe this image would be to call it ‘polyperspectival’, an image of a single earth or world from multiple perspectives. Indeed, this is how we originally conceptualised the visual grammar of the nowcast in a public talk hosted by The Photographer’s Gallery the day after the nowcast was launched.

In reflecting on the work since, we feel that a grammar of fractals is better suited to this earth-image (Engelmann et al., 2022). Whereas a theory of multiple perspectives quietly upholds an underlying unity or whole, fractals better communicate what Gayatri Spivak calls ‘planetarity’, the expression of difference without undoing the possibility of interconnection (Spivak, 2012).

In other words, we want to hold on to the fact that each contributor to the nowcast has a different ontological position – which means a different way of being in relation to the earth and the climate crisis. They are not just seeing or witnessing the earth from different angles, they are also living and weathering it in fundamentally different ways.

A fractal composition of the nowcast becomes evident when reading the field notes. A contributor calling themselves ‘Barfrost’ based near the cartographic north pole in Kirkenes, Norway reported the fact that southern insects are now surviving the winter.

Cédrick Tshimbalanga, an artist in Kinshasa, DR Congo, noted the way the sun ‘dominates’ in a lengthening dry season (Tshimbalanga, 2021).

Tasha Honey, a farmer in New South Wales, responded that she lives the climate crisis through the decisions she makes about what and when to plant. These are not three perspectives on a single warming planet; they are three people performing different modes of being and existing through the climate crisis.

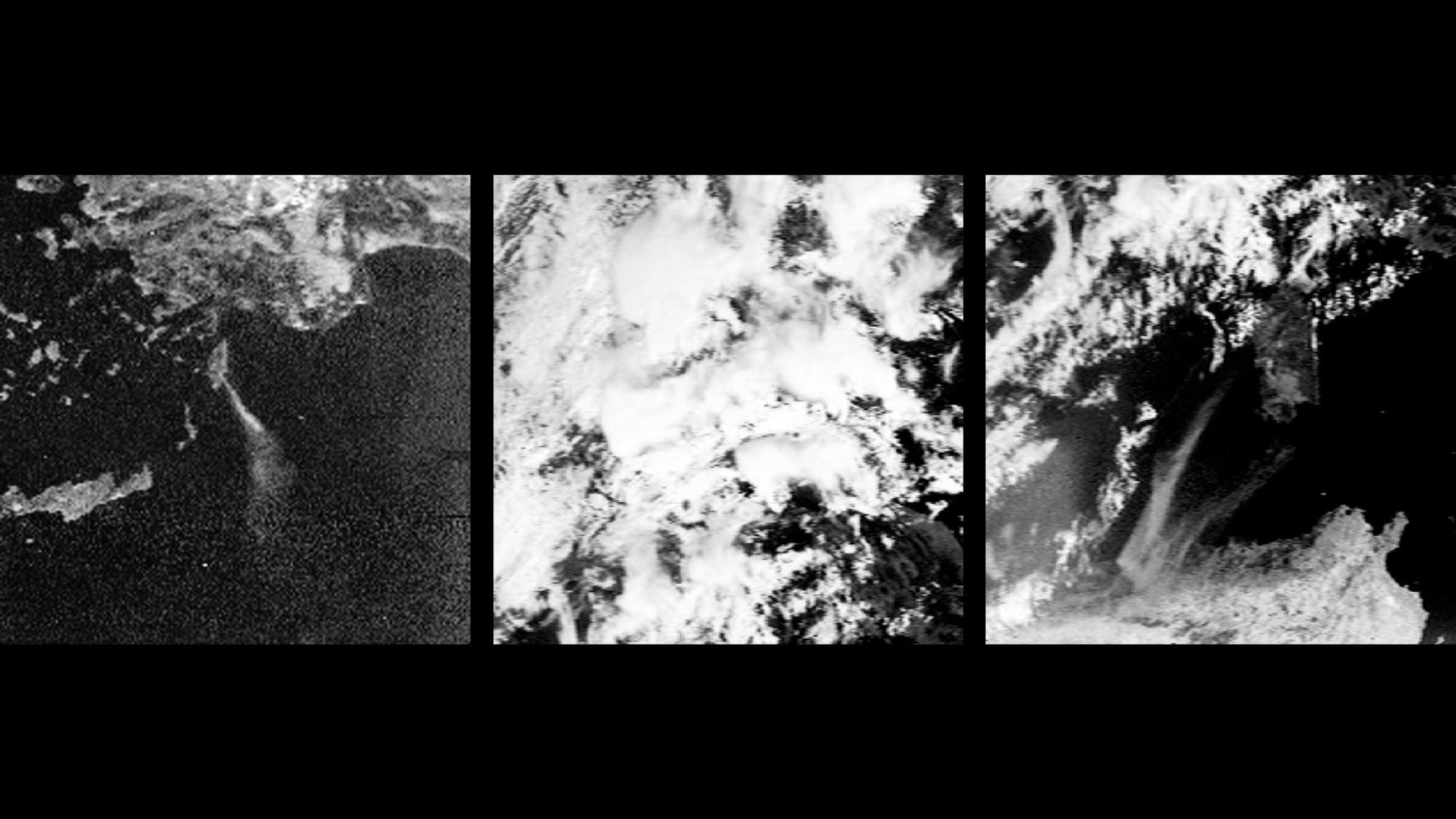

SD: There are multiple ways in which experience is written into images and data.

Each image carries traces of the location of the ground station and its operator.

In Stuttgart, the movement of Jasmin Schädler’s body as she tracks the path of the satellite through an already noisy radio environment is written into the image as an interference pattern.

In Mumbai, India, Ankit Sharma’s images are, too, textured and cut short by radio frequency interference and buildings. From the balcony of his apartment block Ankit collects three images lamenting the gathering dust that threatens his laptop.

"Pattern of cloud is the beauty of the nature", writes Yoshi Matsuoka in Japan (Matsuoka, 2021: np). His quadrifilar helix antenna is photographed framed by a cloud. Unlike contributors who came to satellite imagery reception through open-weather, Yoshi has been receiving NOAA weather satellites for decades, since he was a student.

Zack Wettstein, an emergency department doctor in Seattle on the Pacific West Coast writes, “I see the impacts of climate change reverberating in my community and environment.” “I see patients affected by these hazards […] who present with injuries, illness, and exacerbations of their underlying disease” (Wettstein, 2021: np).

In the first nowcast we ran in 2020, Zack could quite literally see in his image the wildfire smoke that he was treating in the lungs of his patients.

SE: The nowcast demonstrates, too, how weather and climate are felt and witnessed in complex ways: how climate might be sensed as immediately as weather, and how knowledge of weather transcends spatial and temporal scales.

Artist and curator Alison Scott was standing in a park on the Southside of Glasgow, holding a turnstile antenna to the sky in the midst of heavy rain. To keep her laptop dry, she had fashioned a shelter from a set of umbrellas. In this uncomfortable and very wet position, the sound of the satellite transmission comes brightly through the static, through the cloud. Multiple scales intersect: Alison collects an image of a cyclonic weather system taken from 1000 km above, while she is thoroughly immersed, exposed, and sheltering from this same weather system.

Alison’s descriptions of the climate crisis in Glasgow have a similar material and temporal immediacy: like weather, they are happening right now. She says:

Climate change is felt… in a lack of public transport resilience; in bike lanes being opened (and closed)… the neglect of public space and the diminishment of green space; the corporate hijacking of COP26 and the city’s unpreparedness for its scale; …the erosion of rogue-landlord-ed sandstone tenement buildings in need of retro-fitting. (Scott, 2021: np)

"In this uncomfortable and very wet position, the sound of the satellite transmission comes brightly through the static, through the cloud", wrote artist Alison Scott in Glasgow, Scotland. Multiple scales intersect: Alison collects an image of a cyclonic weather system taken from 800 km above, while she is thoroughly immersed, exposed, and sheltering from this same weather system. Composite image: open-weather. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

In Argentina, cartographer and marine technician Joaquín Ezcurra and journalist Aimée Juhazs are in the Parque Nacional Ciervo de los Pantanos. They describe, “a day of unexpected low temperatures,” after the arrival of the cold Sudestada Wind, and add that, “indigenous communities living in the delta of the Parana River… are suffering dearly from both low levels of water, and increasing number of fires during the winter dry season” (Ezcurra and Juhazs, 2021: np).

Joaquin and Aimee remind us how climatic and weather conditions register in the livelihoods of communities with specific historical relationships to land. In this way they gesture to the ‘sovereignty’ of weather: this means honouring the weather as more than our immediate conditions or an object of measurement: it is histories, lifeworlds and relations too (Wright and Tofa, 2021).

"From our ground station, we could see the Tala trees forest in the Barranca, [and] many islands of Cortaderas (Pampa's grass)", wrote cartographer and marine technician Joaquín Ezcurra and Aimée Juhazs in the Parque Nacional Ciervo de los Pantanos, Campana. Composite image: open-weather. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

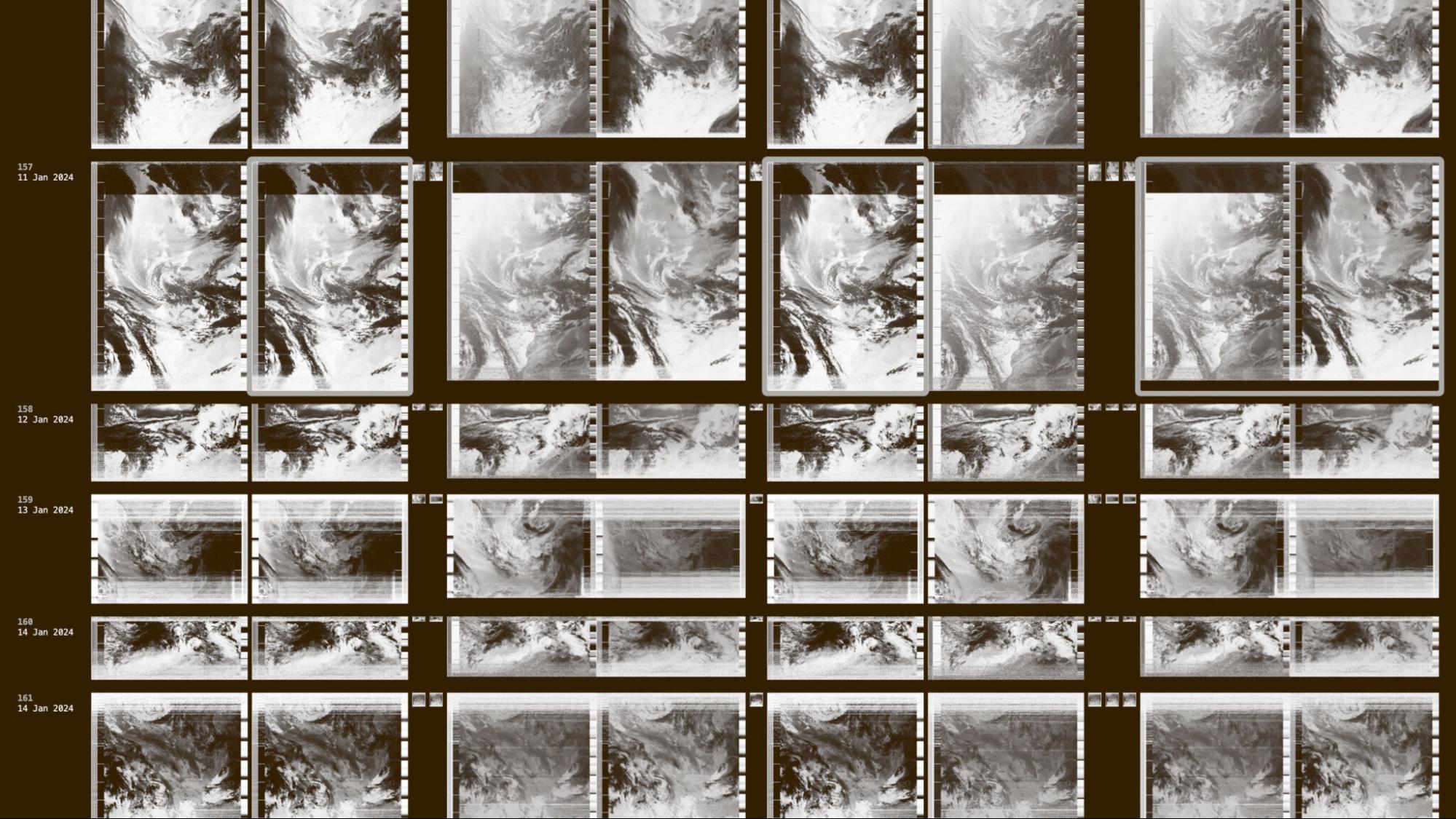

III. Year of Weather

SD: Responding to feedback gathered from contributors, we are currently shifting our focus in two ways. From one-off nowcasts toward a lower intensity, growing, ever evolving – or ‘thickening’ – collective map of planetary weather.

We are tentatively calling this project the Year of Weather.

Our emphasis has shifted from activating and building a network of DIY satellite ground station operators that can collectively image the earth and its weather systems to asking how do we read these images? By extension, how to read the weather?

How might we foreground a plurality of ways of reading and writing weather that include but exceed scientific knowledge of weather and climate?

We will briefly share two examples that have moved our thinking so far.

Weather patterns

First, we are working to produce a set of tools to read ‘weather patterns’ in satellite imagery.

Weather patterns are commonly occurring high and low-pressure systems over a given region.

Conventionally, weather patterns are derived from Sea Level Pressure readings, however relevant to our interests, cloud-cover in satellite imagery could also be used to identify patterns.

Of interest to us, too, is how weather patterns can be a bridge between weather and climate. For scientist Celia Martins-Puertas, ‘weather patterns are climate footprints’ (Martins-Puertas and Engelmann, personal communication, 2023).

Beginning in the UK, we are working to produce a series of visual or ‘citizen’ weather patterns’. Our goal is for these patterns to be used as a tool to read images in the open-weather archive, and as an education resource targeted at UK schools.

Figure: 10: Spanish language talk recorded on location in London and Vienna for Chilean sound arts organisation Arte Sonoro Tsonami on the occasion of the festival, Atmosférica: Semana de la Escucha. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

Poetic evidence

SE: Keeping with our efforts to privilege multiple ways of reading and writing weather, we are also exploring situated, experiential and poetic literacies.

In a recent close-reading of Joan Naviyuk Kane’s poem ‘Exceeding Beringia’, Eyak geographer Jen Rose Smith advocates for, “a turn toward poetry as a form of evidence” (Smith: 2021, 159). Smith shows how Kane’s poem records experiences of change, though not in terms legible to science. Chronicling the “seasonal return and transit” of the red phalarope bird, the poem offers an ‘overlooked dataset’ (Smith, 2021). Here, expertise “is not an ability to measure and record change, but to maintain kinship” (Smith, 2021: 170).

Recognising that weather and climate literacies evolve from situated and sovereign relations to land, we are entering a stage of the project in which we foresee developing a set of relationships with specific groups, including seaweed harvesters and growers in the UK to co-create to weather readings and writings grounded in these contexts.

Infrastructure for weather readings

Figure 11: Behind the scenes: an internal tool we built for remote collaboration, developed by Rectangle. Photo Credit: Open Weather.

SD: We are in the middle of building an infrastructure to support this work.

Learning from the ‘feminist infrastructures’ of Jennifer Hamilton, Tessa Zettel and Astrida Neimanis (2021), we are building a set of digital tools that can be activated by us in workshops, but also engaged with more widely or ‘low stakes’ ways by the collaborators and contributors to the project.

We are working on a submission process for people to be able to decode and upload their imagery, weather notes, readings and other documentation to our archive. And, for them to be able to immediately see their contribution georeferenced and projected alongside others.

Together with our collaborators, we are solving many technical problems, such as figuring out how to geo-reference and map-project satellite imagery. None of these technical questions are neutral.

For example: how do we validate the time people enter without privileging UTC time?

Or how do we process the imagery to elevate different meteorological features and imaginaries?

We are also working on different ways to view and navigate the Public Archive.

SE: Unlike the two nowcasts, the Year of Weather will be a longer, durational inquiry into our changing relations to weather and climate.

In embarking on this phase of the project, we are led by the following question, one that we want to end with here:

How can the project honour and amplify a plurality of weather and climate literacies, while developing pedagogical tools to expand our awareness and knowledge of emergent weather patterns?

Thank you.

Tutorial Links:

References

Calvillo, N. (2023). Aeropolis: Queering Air in toxicpolluted worlds. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City.

Chen, M. Y. (2012). Animacies: Biopolitics, racial mattering, and queer affect. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Engelmann, S., Dyer, S., Malcolm, L., & Powers, D. (2022). Open-weather: Speculative-feminist propositions for planetary images in an era of climate crisis. Geoforum, 137, 237-247.

Engelmann, S. (for open-weather) (forthcoming). Wind’s animacies. Media + Environment.

Ezcurra, J. and Juhasz, A. (2021). Field notes submitted to the open-weather nowcast for COP26. See: https://cop26-nowcast.open-weather.community/

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2018). On heat. Canadian Art, Available at: https://canadianart.ca/features/on-heat/

Kurgan, L. (2013). Close up at a distance: Mapping, technology, and politics. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Leslie, E. (2021). Fog, froth and foam: Insubstantial matters in substantive atmospheres. In: Electric Brine. Berlin, Germany: Archive Press.

Martins-Puertas, C. and Engelmann, S. (2023), personal communication.

Matsuoka, Y. (2021). Field notes submitted to the open-weather nowcast for COP26. See: https://cop26-nowcast.open-weather.community/

Hamilton, J. M., Zettel, T., & Neimanis, A. (2021). Feminist infrastructure for better weathering. Australian Feminist Studies, 36(109), 237-259.

Sabin, L., & Cantos, J. O. (2023). Weathering Saharan dust beyond the Spanish Mediterranean Basin: An interdisciplinary dialogue. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 41(6), 1036-1057.

Scott, A., (2021). Field Notes submitted to the open-weather nowcast for COP26. See: https://cop26-nowcast.open-weather.community/

Smith, J. R. (2021). “Exceeding Beringia”: Upending universal human events and wayward transits in Arctic spaces. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(1), 158-175.

Spivak, G.C. (2012). An aesthetic education in the era of globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tshimbalanga, C., (2021). Field notes submitted to the open-weather nowcast for COP26. See: https://cop26-nowcast.open-weather.community/

Wettstein, Z., (2021). Field notes submitted to the open-weather nowcast for COP26. See: https://cop26-nowcast.open-weather.community/

Wright, S., & Tofa, M. (2021). Weather geographies: Talking about the weather, considering diverse sovereignties. Progress in Human Geography, 45(5), 1126-1146.